Feeding the funnel: strategies for continuous asset evaluation

David A. Wood

Consultant

Lincoln, England

An oil company evaluates potential additions to its investment portfolio in a process analogous to a funnel and filter (Fig. 1). It introduces a large number of assets into the first stage of the process (top of the funnel) and passes them through a series of compatibility tests (filters) to identify those that meet its investment criteria. A relatively small number of assets can pass through all the filters in the funnel and be successfully negotiated for entry into the company's portfolio.

The first four filters are critical not only in ensuring that projects compatible with the existing portfolio and strategy are selected but also in avoiding wastes of time and resources in detailed valuation of unsuitable assets.

Many companies dive straight into detailed valuation of an asset without sufficient regard for these four important filters.

A well-structured portfolio group with an established model of its organization's existing portfolio and a clear grasp of corporate strategy and political risks associated with the assets under consideration should be able to pass assets through the first four filters efficiently.

It then can concentrate detailed evaluation on the most suitable assets. It begins negotiation of terms on assets passing the detailed-evaluation hurdle with the aid of risked values and sensitivities from the associated evaluation models and an assessment of the potential impact on the existing portfolio.

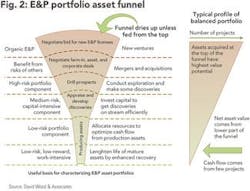

The funnel analogy can also be used in a different sense to describe the type and character of asset in a well established and balanced exploration and production portfolio (Fig. 2).

It is a misconception of many companies that a balanced E&P portfolio contains equal numbers of production, development, and exploration assets. The reality is much more demanding.

In order to sustain growth and replace its petroleum reserve base (by at least 100% of each year's production, as investors demand), a company usually needs to include a larger number of less mature assets (exploration, appraisal, and immature development) in its portfolio than producing assets.

The production assets are essential as they provide the cash flow and need to be of high quality and ideally of long life. However, they progressively deplete the reserve base, which must be replenished by bringing the less mature assets into production. This is risky because many assets tested fail to deliver reserves or production. It is also costly.

Generic strategies

Most petroleum companies adopt one or more of the following generic strategies in order to keep the asset portfolio funnel continuously fed from the top and maintain this requirement for a continuous addition of new ventures:

- Focus on organic growth by finding and signing exploration licenses and prospects. This requires specific exploration skill and high-risk investment with the ability to accept that the majority of prospects tested will end in dry holes. Discoveries, however, are likely to lead to substantial additions to reserves.

- Farm in to exploration licenses in which initial exploration work has high-graded prospects. This strategy usually involves paying an initial premium to enter prospective licenses but can save considerable time in the license negotiation phase, reduce political and technical risk, and avoid the need for establishing and maintaining new-venture exploration expertise in a wide range of geographic regions.

- Acquire field discoveries or immature field developments by paying an acquisition fee for proven and part of probable reserves, and capitalize on the exploratory risk-taking of others. This strategy requires significant capital both for field development and reserves acquisition and usually depends on step-out exploration drilling success to prove up probable and possible reserves to be financially worthwhile for the acquirer.

- Acquire mature reserves and production. This can be a viable strategy at the right price. It is a strategy that has worked for several independent producers buying mature fields from majors for which the reserves ceased to be material, cutting costs, or tying back small satellite fields to improve reserves and returns. This strategy generally works only up to a point in terms of reserves replacement as by their nature such assets are depleting rapidly. It is, however, a good strategy for setting up a hub for a company in a new area. An example is Apache Corp.'s acquisition of Forties field from BP PLC in the North Sea in 2003.

- Combinations of some or all of the above. Most companies do not adopt just one of the above strategies but use a combination of them. However, most companies have experience and success with one or two of these strategies rather than with all of them.

A company's approach to portfolio management, strategic development, and growth has to address this requirement to replace reserves through new ventures. Otherwise, it will simply liquidate its existing reserves, and its asset base will shrink.

The author

David A. Wood ([email protected]) is an international exploration and production consultant specializing in the integration of technical and economic evaluation with management and acquisitions strategy. He also provides an extensive range of training on upstream economics, international fiscal terms, and strategic portfolio and risk analysis, both as an independent trainer and on behalf of several training organizations (see www.dwasolutions.com). After receiving a PhD in geochemistry from Imperial College in London, Wood conducted deep-sea drilling research and in the early 1980s worked with Phillips Petroleum Co. and Amoco Corp. on E&P projects in Africa and Europe. During 1987-93, he managed several independent Canadian E&P companies (Lundin Group), working in South America, the Middle East, and the Far East. During 1993-98, he acquired and managed a portfolio of onshore UK and North Sea companies and assets before becoming a consultant. Wood is the author of four Oil & Gas Journal Executive Reports on risk analysis and related subjects (see box.)

About this series

This series addresses fundamental issues of petroleum asset-portfolio management. The material is drawn from training courses in strategic portfolio management that the author has developed for the petroleum industry since 1998. The author writes in greater detail about these subjects in four executive reports available for purchase through the Online Research Center of Oil & Gas Journal Online. For a list of titles and descriptions, go to www.ogjonline.com, click "Online Research Center" on the left navigation bar, then click the link under "OGJ Executive Reports."