Portfolio-management concepts help analysis, lending decisions

Modern portfolio management involves the use of a range of sophisticated mathematical models that have evolved together with the capabilities of modern computers. Examples include Monte Carlo simulation, simplex and genetic optimization, real options, and dynamic decision trees.

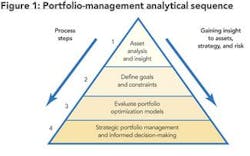

This author is an enthusiastic proponent of these techniques and of a systematic, appropriately managed approach to strategic risk and portfolio analysis. To be most effective, portfolio models should employ an analytical sequence that starts with a comprehensive understanding of the assets and defined strategic goals and constraints (Figure 1).

Discouraged by model complexities and computer limitations, many companies have been managing their portfolios for many years without sufficient regard for Step 3 (optimization). Traditional portfolio management employs asset analysis performed with simple unrisked, discounted cash-flow methods and portfolio selection (asset optimization) based upon a simple rank-and-cut process. Many smaller companies continue to rely on such an approach and, by taking account of some basic portfolio-management principles, can do so successfully. However, methods are available that more systematically integrate risk, strategy, and sophisticated optimization algorithms. In the long run, the more-sophisticated and integrated methods should outperform traditional approaches.

Computational limits are receding. The larger information-technology vendors to the petroleum industry are developing all-encompassing, worldwide-web-driven, and modular project-evaluation software integrating corporate-wide project databases with economics, risk, and portfolio analysis modules that can share data and analysis. The new software allows established economic portfolio-theory concepts, such as the efficient frontier, to be readily applied to a company's worldwide portfolio of assets and to be easily updated.1 The sophisticated models that result remain expensive, however, and generally are within reach only of large companies with substantial asset bases and sufficient resources to benefit from the full range of their data-handling and manipulation capabilities.

There is much more to successful portfolio management than defining an efficient frontier, of course, and having access to a sophisticated computer model is no guarantee of optimal decisions and outcomes. Nevertheless, employing such models and structured analysis is certainly less risky than relying on intuition or unrisked approaches.

More worrying is the potential for misapplication of sophisticated portfolio tools by analysts with only sketchy understanding of a company's asset base and strategic goals. Faulty analysis can condemn pivotal portfolio assets or recommend acquisition of incompatible assets. This can happen if decision-makers rely on portfolio analysis without fully understanding the assumptions and constraints built into the models. Alternatively, if senior managers do not have the time to understand the workings of these integrated analytical models, or if they feel intimidated by the technology, complex numerical algorithms, or mathematics employed by them, they are less likely to rely upon the analysis they provide. Analysts and managers alike need to know how to apply basic portfolio concepts to petroleum-industry decisions and how to operate the software tools increasingly available to assist them.

Articles in the series beginning here will focus on basic portfolio concepts. They will help decision-makers evaluate portfolio models, encourage analysts who construct the models to improve their understanding of asset bases and strategic influences, and address the structure and operation of an effective portfolio-management team.

Four principles

Portfolio models will not improve portfolio performance on their own. The models are only tools to assist portfolio management and decision-making. They should not drive the process by themselves.

Managers should apply four portfolio-management principles integrated with a strategy defined by measurable goals. Within that framework, a portfolio manager can effectively use a portfolio model to make decisions that optimize portfolio value (Figure 2).

The principles are diversification to reduce risk, adequate sources of funding, balanced mix of assets to provide growth, and operating efficiently to optimize cash flow. The principles apply as well to downstream and trading assets as they do to upstream assets. Indeed, it is crucial for integrated companies to manage at the corporate level the full spectrum of their assets as a single portfolio, or at least to integrate separate models for upstream, downstream, and other sectors.

Assessing the ability of a petroleum asset to generate satisfactory returns on investment requires more than arms'-length analysis of engineering reports and contracts. The restricted approaches of too many project lenders and industry analysts fail to consider the comprehensive interactions of uncertainty associated with every asset and how those interactions affect the company's portfolio value and risk. Those issues can be crucial to the success or failure of nonrecourse project financing. Because there have been many failures of loans of this type, in fact, some banks have withdrawn from petroleum project finance.

If lenders analyzed not only the asset considered for financing but also the contribution of that asset to the operator's portfolio and its relationship to strategy, they would be better able to identify successful projects. This suggests that lenders and analysts, too, could benefit from a clearer understanding than many of them now possess of petroleum portfolio-management principles.

References

1. Markowitz, H.M., "Portfolio selection," Journal of Finance, Vol. 7, March 1952, p. 52.

The author

David A. Wood (woodda@compuserve. com) is an international exploration and production consultant specializing in the integration of technical and economic evaluation with management and acquisitions strategy. After receiving a PhD in geochemistry from Imperial College in London, Wood conducted deep-sea drilling research and in the early 1980s worked with Phillips Petroleum Co. and Amoco Corp. on E&P projects in Africa and Europe. During 1987-93, he managed several independent Canadian E&P companies (Lundin Group), working in South America, the Middle East, and the Far East. During 1993-98, he acquired and managed a portfolio of onshore UK and North Sea companies and assets before becoming a consultant.