The Danish Twist

Those who lead a quiet life, lead a good life." That has been the historically resounding proverb for the Danes when it comes to business – and its oil and gas industry is no exception. Upon arriving in Copenhagen, one senses that everyone abides by the same rules: you do not shout about what you do, you do not boast to your neighbors, and you should never ever assume you are better than the next person. Even commuting to work is a humble affair: from politicians to CEOs to delivery boys, 50% of Copenhageners commute by bicycle, each one hidden amongst the rush of other cyclists on the town's busy streets.

This sponsored supplement was produced by Focus Reports. Publisher: Ines Nandin; Project Coordinator: Kirsty Avril Jane Walker; Editorial Coordinator: Herbert Mosmuller; For exclusive interviews and more info, plus log onto energy.focusreports.net or write to [email protected]

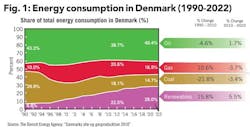

This modest approach could also be used to describe the country's attitude towards its energy industry. Few people know that Denmark is the only country in the European Union that supplies all of its own energy. For the last few years, Denmark's energy production has been about 20% higher than its energy consumption.

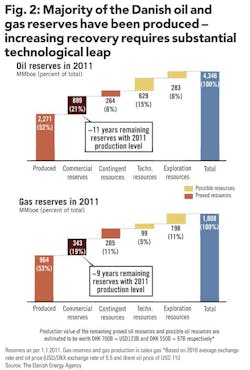

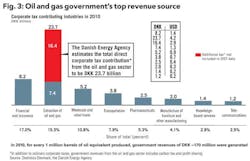

Denmark is still one of Europe's biggest oil and gas producers. Figures from 2012 show that a proven 870 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) lurk under the extremely tight chalk of the Danish Continental Shelf (DCS). This means a supply of black energy for roughly the next 10 years at current rates of consumption. While Denmark's reserves may not be the largest, the country nonetheless is producing 0.3% of the world's oil. That's good news for government, too, as just last year the industry generated $5.2 billion in tax revenues. So a change in the traditionally reserved attitude appears to be creeping in: it seems both the public and the private sector are taking notice of their neighbors' backyards and wondering just what lies in their own.

The Danish Energy Agency (DEA) forecasts that oil production will drop 30% by 2014, but this has not overshadowed the country's remaining potential. Denmark has made some substantial technological contributions to the global oil and gas industry, such as the horizontal drilling techniques developed by the Danish Underground Consortium (DUC). The challenge lies now in that even more innovation will be needed to increase extraction rates from the country's mature chalk fields. Each percentage increase in the extraction rate means more than $8 billion gross value at today's rates.

Innovation requires talent and investment. But investment requires Denmark to communicate its stability and potential more forcefully.

Over the first months of 2013, the government announced a change in tax regime on oil and gas revenues for companies producing in the Danish North Sea, proposing "a level playing field" for them. "We believe it will provide us with a more modern and neutral tax system in the North Sea than we have right now," said Bjarne Corydon, Denmark's Minster of Finance. As such, the DEA – together with Martin Lidegaard, the Minister of Climate, Energy and Building – will organize the 7th licensing round for fields in the DCS, attracting more attention and brining more investment to the Danish North Sea stronghold. The ambition is to organize the round before the end of 2013.

On May 1, 2012 the industry's new voice, Oil Gas Denmark (OGD), opened its doors to make the country more visible on the world energy map. Copenhagen is now a candidate to host the next World Petroleum Congress, which would bring the country an extra boost and more recognition. Martin Næsby, managing director for OGD, said, "A key focus of the association is on the continued development of the service companies that supply the oil industry. Internationalization is also part of this: Danish service companies that have matured in the Danish sector of the North Sea are now applying for projects in Brazil or Norway."

Indeed, many companies that have contributed to Denmark's status on the international scene learned from the highly challenging conditions in the Danish North Sea and took that expertise abroad.

Yet despite these advancements in the oil and gas sector, there is a twist in the country's energy focus. In addition to its expertise in black energy, Denmark has set perhaps the most ambitious targets for green energy the world has seen so far. The government has established the goal of being 100% powered by renewable energy as of 2050. Lidegaard reiterates, "We want to be self-sufficient and prove that it is possible for a modern welfare state to become independent of fossil fuels in 30-40 years' time."

This growing political focus on renewable energy prioritizes offshore wind and that is drawing resources and top talent away from the oil and gas industry. Lidegaard offers assurances that this way of dealing with Denmark's energy future is not intended as an aggressive opposition to the oil industry; rather they go hand-in-hand. "The Danish parliament is completely green when it comes to the Danish demand, but we are also in complete agreement that we should be a part of the fossil fuel supply system, as long as international demand remains," said Lidegaard.

Despite this assurance, the spotlight is certainly cast on green, with black in the supporting role. That raises questions: Is the oil and gas industry merely an instrument to pay for Denmark's ‘green transition'? Or can the two offshore industries work together to create the right energy mix for Denmark?

After all one must not forget, as Næsby states, that the Danish oil and gas industry "represents 15,000 work places; $8.4 billion; 9% of Danish exports, and a great deal of innovation."

E&P on the DCS: a never-ending story?

Never before has the Danish oil and gas industry seen its three operators so active at the same time: with Maersk Oil and its partners Shell and Chevron responsible for 85% of production, DONG E&P 10% and Hess 5%. All three have new building projects going on, as well as extensive modifications of existing installations due to changing environmental and reservoir conditions, ageing of the installations and technical development.

Denmark's current oil and gas production comes exclusively from mature chalk fields, an area the country has developed great expertise in. "The techniques used globally in the production from tight reservoirs have for an important part been developed in Denmark," said Peter Helmer Steen, CEO of national oil company North Sea Fund (NSF) which has been the state participant since 2005 and holds a 20% stake in all licenses as a commercial partner. Indeed, many of the techniques Steen refers to have been developed or improved by the DUC, which traditionally has dominated exploration and production on the Danish continental shelf. DUC is comprised of Maersk Oil (operator) along with Shell, Chevron, and since July 2012, NSF.

Another example is Welltec. "Welltec has looked at great new ways to decrease the costs of wells," said Steen. "If we wish to produce more than the current percentage, we need to keep costs low in all aspects of drilling, and the completion techniques that Welltec is working with could be a possible cost reduction in the completion of these wells."

Interestingly, Welltec, which has developed from a start-up to generating $300 million annual revenue in under 20 years, did not develop from a focus on Denmark, but on northern neighbor Norway. "We decided from day one to be an international company," Welltec founder and CEO Jorgen Hallundbæk told Focus Reports. "Even on our website, you have to look carefully before you will find anything Danish and that is fully intentional; why consider to be tied to one market when you have the entire world to play with?"

Today, the rest of the world should look up and take notice of what is happening in Norway when it comes to enhanced oil recovery, Hallundbæk explained. "Norway has been focusing on enhancing recovery rates for more than 20 years and still today is the global benchmark for enhanced oil recovery," said Hallundbæk, adding that, "The rest of the world and the other North Sea countries are not there yet." According to Hallundbæk, "Denmark is still at an average point in terms of recovery factors, and the UK is nowhere near the levels of Norway."

Denmark could take Hallundbæk's comments as clear advice. Nonetheless, the Danish industry takes pride in the significant rise of its extraction rates over the past decades. "The current recovery rate is around 26-27%, which is low in comparison with other producers such as Norway," said Martin Næsby, OGD managing director. "We should consider, however, that it went up from 5-6% on the outset, and seen in that light it actually is a great achievement."

Indeed the phrase ‘vacuum-cleaning the Danish Continental Shelf' recurred several times throughout our interviews with Denmark's operators. "At the outset, DONG focused on small field development, or ‘vacuum cleaning' as we like to call our activities on the DCS," said Soren Gath Hansen, vice president DONG E&P. "Our Siri-field is a success story as we have actually been able to keep the area alive by vacuum cleaning."

That is one kind of strategy and it takes a particular kind of company, but Hansen realized that he would not be able to develop the company and the portfolio on the long term only focusing on late-life fields and vacuum cleaning. "Although one of our largest developments, the Hejre-field, is in Denmark, almost 70% of our production actually comes from Norway today, while we are also investing heavily west of Shetland. DONG is the biggest holder of acreage in that area," Hansen said.

The Hejre-field that Hansen refers to is one of the most significant developments that the DCS has seen in a long time. DONG estimates probable reserves at 44,000 boe/day, most of it oil. More significantly, Hejre is the first field coming into production that is not situated in the low-temperature and low-pressure chalk fields in the southern part of the Danish North Sea.

The water-depth at 60/65 meters is slightly deeper than existing producing fields, but some of the reservoirs are also more challenging than the traditional mature chalk fields. "The Hejre-field is the first High Pressure, High Temperature (HPHT) field put in production in Denmark, and a good example of the not-so-low hanging fruit on the DCS," said Flemming Horn Nielsen, country manager Denmark, DONG E&P.

The question, however, is how much of this not-so-low hanging fruit will be harvested. While a recent find by Wintershall of potentially 100 million barrels of recoverable oil in the Hibonite exploration well inspired hope, the number of appraisal drillings in the past three years averages close to zero for Denmark. Furthermore, oil production is declining rapidly and a mid-size player in the Danish context, Bayerngas, recently announced it might pull out of Denmark, citing far-reaching changes in the tax regime and consequent devaluation of its assets. "Denmark no longer appears attractive," Bayerngas' country director Denmark, Trond Bjerkan, said. "We have stopped all preparations for bidding in the next licensing round because it no longer makes sense."

Bayerngas responded to government efforts to harmonize the different tax arrangements under which oil companies currently operate on the DCS. The amendments follow a 12-month investigation into the possibility to change a deal, the North Sea Agreement, which the former government made with the DUC in 2003. When the current government realized that it could not change taxes for the DUC without setting off costly compensation clauses in the contract, it instead took the tax rules that the DUC operates under and applied them to the rest of the oil companies operating in the Danish North Sea.

Whether this is the right strategy to optimize exploration and production is hotly debated by key stakeholders of Denmark's energy industry. "It is extremely important for the Danish government to realize that the country is a net exporter of oil and gas and that the oil and gas industry generates around $30 billion in tax revenues, but also that the extraction rate stands at a mere 27% for the current fields while the world is screaming for more energy," said Steen Brødbæk, CEO of Semco Maritime, a project engineering company and one of Denmark's fastest growing energy companies of the past decade. "We cannot produce enough energy to substitute the growth rate for countries outside of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)," Brødbæk added. "Therefore, Denmark has to continue exploring as the UK and Norway are doing. We need the government to support that strategy. If they do not, the outcome is easy to predict. This is an international business and international oil companies are putting their money where they can get most back."

In a response to industry criticism, Finance Minister Bjarne Corydon told Focus Reports that, "The rules that apply to new concessions for the DUC partners under the North Sea Agreement should also apply to the concessions handed out before 2004. We are creating a level playing field, more neutral taxation, and we are enhancing revenues for a nation that has to invest in growth."

Corydon can put forward that Maersk Oil announced its plan to invest $800 million in the development of Tyra South East, the largest investment by the DUC partners since the approval of Halfdan Phase 4 in 2007, only weeks after the proposal came out, a decision taken on the basis of the new tax rules. However, critics would say that this again is not an example of the type of forward-looking activity that the DCS needs in order to avoid becoming a sunset production area.

Asked about the significance of the DCS for Maersk Oil, VP of Exploration Lars Nydahl Jørgensen, Vice President, Head of Exploration, Maersk Oil said: "It is clear that the Danish Continental Shelf is a mature area where exploration has been going on for many years. I would like to point out Johan Sverdrup in Norway. Forty years and four generations of exploration had been going on with companies coming in and trying their best, and still Johan Sverdrup was not found."

Before the end of this year the DEA hopes to organize the 7th licensing round. "My expectations are high. A lot of good, new data has been developed in the last years," said Peter Helmer Steen of NSF. "Denmark has been known for many years as a chalk reservoir. Therefore much of the seismic investigation has been targeted to chalk. The other layers have not been targeted that much, which perhaps has led some opportunities to stay below the radar until now."

"Data collected since the 6th licensing round in 2006 indicates that there is a lot of oil left in the Danish subsoil," Steen said. "It is not easy oil, but very interesting nonetheless."

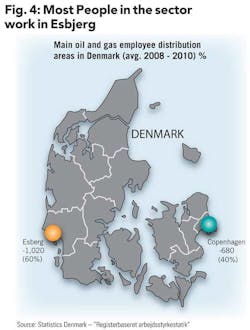

Esbjerg: the Missing Link?

The board of the World Energy Cities Partnership (WECP), a non-profit organization comprised of the mayors of the different member cities, will soon welcome Johnny Søtrup as its 20th member. Søtrup is the mayor of Esbjerg, a city of 70,000 on the Danish west coast, 709 km south of fellow member city, Stavanger.

It might come as a surprise to some to see the name of Esbjerg among the likes of Aberdeen, Houston, Stavanger, Port Harcourt, Perth, Luanda, and Villahermosa. But to Søtrup it is logical. "We bring a new dimension to the table among these 19 members," Søtrup said. "We are undoubtedly the member with the biggest offshore wind industry. On top of that, we are a frontrunner in uniting that offshore wind industry with our offshore oil and gas industry."

For Esbjerg, joining this organization is an acknowledgment of its contributions to the global energy industry. But the title of ‘Member City' brings more. The WECP is not just a way to share experiences, but to actually capitalize on member's expertise and set up partnerships between organizations and companies.

Esbjerg's success can be seen as proof that the green profile of Denmark's energy policy actually has positive effects on the country's oil and gas industry. "The city of Esbjerg is the best illustration that we do not see our green energy industry as a substitute for an economically efficient and progressive way of using our oil resources: its offshore industry mixes both green and black, and many local companies have a foot in both," Minister of Finance Bjarne Corydon said. "It is the same companies and decision makers, successfully harnessing both sectors."

Indeed, many of Esbjerg's key oil and gas players have been quick to grasp opportunities resulting from the national government's push for a greener energy mix. Their expertise was happily welcomed by a wind industry that desperately needed to build up offshore expertise. "The first offshore wind park was constructed by a company that had experience building these parks onshore," said Steen Brødbæk, CEO of Semco Maritime. "They ran into serious trouble dealing with the harsh environment and weather conditions. Now they are using competences from the oil and gas industry and leaning heavily on the oil and gas industry's supply chain."

Still, the marriage between te city's oil and gas and wind industry is not perfect. "Just two years back, most Danes thought that the oil and gas industry would close down within a couple of years and that the industry would be fully replaced by renewables, mainly offshore wind," said Henrik Hansen, CEO and founder of Q-Star Energy, a provider of multi-skilled manpower to the oil and gas and renewables industry. "This made it very hard to attract new people to the oil and gas industry; they simply did not believe there was a future and would prefer to work in wind energy." Hansen knows the challenge all too well, with around 300 of his people active on North Sea platforms.

Although it remains a serious challenge, the shortage of human resources for Esbjerg's oil and gas industry seems to be changing, and in the right direction. "I am confident that, in a couple of years, young people will start looking at the oil and gas business again and realize that it is a viable and even attractive alternative," Hansen said. "Also, in Esbjerg we clearly show that it is possible to swap between the oil and gas and the renewables industry and that it is possible to apply expertise and experience from the oil and gas industry in the renewables industry."

People familiar with the city's business community maintain that it is more than a good geographic location that has led to Esbjerg's success. "Many cities in Denmark have seen industries crucial to their economy leave, and they have to do something different now," said Anders Eldrup, the chairman of Offshore Center Denmark and former CEO of DONG Energy. "Many are waiting for something to happen; in Esbjerg they do not wait, they just start something new. It would be great if we could make the spirit of Esbjerg spread to the rest of the country."

Blue Water Shipping, a provider of freight solutions, seems to be an exponent of this praised Esbjerg mentality, transporting oil rigs to every corner of the planet. Thomas Bek, global manager of the company's oil and gas division said: "Since the early years of the Danish oil and gas industry, Blue Water has supplied drilling equipment to the industry, with shipments ranging from small courier parcels containing o-rings to project transport of complete oil rigs to the Middle East, the North Sea, Irish Sea and West of Shetland, Atlantic Frontier, the Faroe Islands and Greenland, and the Far East. Also, we have a particularly strong position in Central Asia."

Asked how on earth an Esbjerg-based company developed a particular expertise in dealing with freight in one of the former Soviet Union's most remote areas, Bek explained: "One of the biggest customers we have in the industry is Keppel, the world's largest rig manufacturer, and it was through this relationship that we went into the Caspian. We move around with our customers. That also means that, when we are entering a new market, it is not necessarily part of a long term strategic decision that took years to develop; it can also be an opportunity that shows up."

Still, parts of the virtues ascribed to Esbjerg are born out of necessity. "The willingness to do something else is crucial," said Søren Fløe Knudsen, CEO of Danbor, Esbjerg's largest offshore base with operations in Australia, Brazil, Venezuela, Italy, Norway, and the UK, when asked what enables Esbjerg's business community to box above its weight internationally. "Denmark is a small country but has to be global. We cannot just sit here in Esbjerg and wait for things to happen," he said.

"This does not just go for the biggest companies like Ramboll and Maersk Oil, but also for the smaller and mid-sized companies," Knudsen continued. "Around the North Sea, in Brazil, the Middle East, Asia; many companies have shown that they are capable of capitalizing on opportunities in the oil and gas industry around the world."

Esbjerg is also home to Dancopter, Europe's fastest growing helicopter company between 2009 and 2012. Just ten years ago, Dancopter performed its first flight in Esbjerg. Today, the offshore operation has expanded to 16 helicopters on two continents with the world's most respected oil and gas companies.

"Dancopter has indeed been through a fantastic growth period," said Jens Jensen, managing director. "In 2011, we won the biggest contract in the Danish North Sea, servicing Maersk Oil and the 15 fields of the DUC. A year earlier, in 2010, we had established ourselves in Nigeria through a five-year contract with Shell. We also started to work with Shell from Den Helder in the Netherlands and Norwich in the UK."

Offshore Wind: Causing a Stir

In 1991 Denmark erected its first offshore wind park, and now the country's 2012 Energy Agreement prescribes that Denmark's energy supply must consist of 100% renewables by 2050. Further to this, DONG recently announced that, by 2020, the cost of offshore wind needs to fall to 100 euro per megawatt hour for parks constructed from 2020. Samuel Leupold, DONG Energy Wind Power's new vice president puts it simply, "If it does not happen, we jeopardize our industrial future".

DONG Energy Wind Power, the world's market leader in offshore wind, and responsible for building 38% of European capacity, is fully aware of this responsibility and the challenge of bringing the cost of offshore wind down in order to make it a competitive source of energy. This would enable the wind industry to sit side by side with Denmark's oil and gas industry in keeping the country energy self-sufficient in the years to come.

Leupold is not concerned about delivery, "given that we have accumulated deep know-how all along the value chain, satisfying demand is not a problem… we have the portfolio and all the skills to bring this to life." But Leupold also notes: "Suppliers need to understand that if offshore wind wants to maintain a long-term perspective, we need to make sure that it remains within the cost frame acceptable for society in the long term. We must be able to compete with other alternatives for power generation, and that is why I say that our suppliers must understand that it is in their best interest that they help us be creative, come up with new concepts, industrialize those concepts, develop the value and supply chain to such a degree that the cost really come down to the level we have indicated."

His comments are echoed by Thomas Gellert, COO of CT Offshore, an offshore cable laying company, part of the installation vessel company A2SEA, partly owned by DONG Energy. Gellert feels that "where this industry might be in the verge of taking a wrong turn is in terms of the lack of cooperation between parties especially at early project stages. Otherwise, it might be very difficult to bring down cost to a sustainable level for the industry." He adds, "We can do something as a single entity… We can always strive to complete projects more efficiently, perform early commissioning by using the experience we have. But to really lower the cost of energy is a joint task… it is a matter of joining forces and managing the interfaces."

Michael Hannibal, CEO Offshore E W EMEA OF, Siemens Wind Power remarks on his optimism about bringing down the cost of offshore wind. "Since 1991, we have been able to reduce costs by 40% per decade. These cost reductions have for a very large part been caused by turbine design and turbine innovation. The turbines have grown; they have become more efficient with larger rotors, larger generators and other features resulting in increased production." Hannibal has his work cut out for him, saying that "the answer to the future solution will require companies like Siemens to continue to innovate on the turbines." He concludes that it is not the oil and gas industry they need to look to as a cost example, but the commodities sector to learn how to industrialize and mass produce offshore wind.

So, if offshore wind does not look to the oil and gas industry for cost reduction capabilities, what can green learn from black? Hannibal suggests that harmonized legislation across Europe, as the oil and gas industry has managed to secure, could help. A2SEA CEO Jens Frederik Hansen notes that, "Ultimately, harmonization would drive costs down, and increase visibility on every country's specific procedures."

Leupold, on the other hand, believes that as the wind industry has grown so fast, there are many challenges faced from a managerial, procedural and best-practice point of view. There is still almost a ‘start-up' environment in the industry that would benefit greatly by being more stable and industrial like Denmark's oil and gas industry.

There is one threat that faces the oil and gas industry from offshore wind in Denmark: the ‘brain drain', or migration of talent from the black energy industry to the green one. A2SEA has installed more than 50% of the world's total offshore wind turbine capacity, and although Hansen admitted that "finding highly skilled engineers and professional project managers is always a challenge", he also pointed out that, "Denmark is well recognized for clean energy and wind power and for that reason we receive a large community of international engineers wanting to be part of our unique ability to promote and develop green energy." Moreover, "the growth we have achieved over the last years has given our company a worldwide reputation, and this factor has really improved our capacity to meet and retain the best talent available on the market. Also, we have been working closely with universities, by promoting discussion and debates on wind energy."

Surely this does not sound like the "quiet life" we expect Danes to lead.

Some companies have made the jump into offshore wind from the oil and gas industry where they so comfortably sat, having seen the opportunities and having the ability to leverage their capabilities. One example is Esvagt, a company that operates a fast-growing fleet of Emergency Response and Rescue Vessels (ERRVs) and Anchor Handling Tug Supply (AHTS) vessels in the North Sea from its base in Esbjerg. The company's business was firmly anchored in the oil and gas industry from the start, but talking offshore in Denmark is not just about offshore oil and gas anymore. It is also offshore wind. "Wind energy is decisively moving offshore and there is a requirement for maintenance," Esvagt's managing director Søren Nørgaard Thomsen said. "As the wind turbines are placed further from shore, travelling from shore to the turbines for maintenance takes too much time. We can provide vessels that can act as service ships, where we have technicians on board with a workshop and a warehouse for spare parts."

If companies like Esvagt can successfully leverage capabilities to their advantage both ways in offshore, then perhaps this is where green and black can see eye to eye. The key for Denmark's offshore energy success may lie in making a ‘black and green' industry prosper under a stable government framework.

Denmark has, over the decades, been progressive in developing its energy industry. The Danes were pioneers in exploration and production of oil and gas in the North Sea. They were the first country to develop a district heating system, and now they are driving the development of offshore wind energy.

When asked about the offshore industry from an external perspective, Morten Mønster, partner with Deloitte, summed it up: "I would say that it is black and green. The best way of advancing the development of renewables is to work with the oil industry and integrate the two from a competence perspective. Denmark is a small country, and its unique trait is that we are good at working together. We can apply that in black and green, too. It is not either or, or even transitioning from black to green; it is about offshore together, and combining our different initiatives."