OPEC casting shorter shadow

In the 40 years since the Arab Oil Embargo, the global oil economy has changed dramatically — and so have capital markets.

John White and Gabriel Chavez, Triple Double Advisors LLC, Houston

Last Month, October 17 to be exact, was the 40th anniversary of the Arab Oil Embargo. What has changed in the oil and gas industry since then? Practically everything. As we all know, there have been tremendous improvements in seismic techniques, drilling and completion technology, and, of course, the unprecedented advancements in horizontal drilling and fracture completion.

All of these advancements in exploration and production technology required capital. So how have the E&P capital markets advanced since the oil embargo? The capital markets have grown in tandem with geoscience technologies in size and sophistication. The capital markets have become: 1) more efficient and streamlined, 2) more institutional and sophisticated, and 3) generally more transparent.

Consider an established E&P company launching a drilling partnership in 1977. Funding this structure required several months of time and the involvement of hundreds of retail financial advisors from multiple broker-dealers and hundreds of retail investors.

Compare the complexities and time required for the drilling partnership of 1977 with a secondary offering of common equity today. Established large and mid-capitalization E&P companies can now raise hundreds of millions of dollars in a matter of days. Most of this capital is provided by institutions that are very knowledgeable about the issuer, and the transaction is handled by a handful of investment banks and capital is provided by institutional investors.

How did we get here? In this article, we briefly examine the development of the E&P capital markets in the years after the Arab Oil Embargo. We show how innovations in E&P finance made during this time have complemented advances in geo-science technologies and together have created a renaissance in US oil production. These capital market developments have contributed to making the US less dependent on OPEC imports than at any point in the last 25 years.

To refresh, the Arab Oil Embargo was the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' decision to cut oil exports to the United States, the Netherlands, and Denmark for providing military aid to Israel in the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Initially, exports were to be reduced by 5% per month until Israel evacuated the territories occupied in the Arab-Israeli war of 1967. However, in December, a full oil embargo was imposed and prompted a serious energy crisis in the US and other nations dependent on foreign oil.

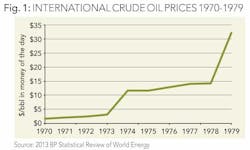

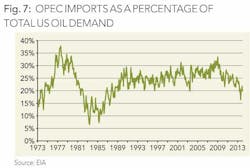

In addition to the physical embargo, OPEC used a series of oil price increases as a political weapon against Israel and its allies. Eventually, the price of oil quadrupled. In March 1974, the embargo was lifted after the US negotiated an agreement between Syria and Israel. Prior to the embargo, oil prices had ranged between $1.80/bbl in 1970 to $3.39/bbl in 1973 (in nominal terms). Oil prices rose to $11.58/bbl in 1974 and remained considerably higher than their pre-embargo level. In the years following the embargo, the US became even more dependent on OPEC oil imports. OPEC imports as a percentage of total US demand rose from 17.2% in 1973 to an all-time high of 30.5% in 1978 and 1979.

This dependency on OPEC imports set the stage for additional oil price escalations in 1979 due to OPEC production instability as a result of the Iranian revolution. The revolution involved the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, who was supported by the US and the UK, and was replaced by an Islamic republic under the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. A combination of strikes by Iranian oilfield workers and another price increase by OPEC sent prices up yet again from $14.02/bbl in 1978 to $31.61/Bbl in 1979 (in nominal terms). See Fig 1.

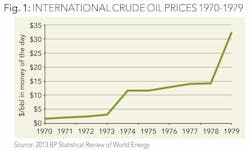

The dramatic increase in the price of oil triggered a huge increase in exploration and production activity in the US and only accelerated following the oil price increases due to the Iranian revolution. See Fig 2.

Funding for this increased E&P activity was provided primarily in the form of public equity, bank debt, and drilling partnerships. Drilling partnerships were widely used vehicles for E&P financing due to the US income tax structure during the late 1970s and early 1980s. During these periods, marginal income tax rates ranged from 39% on an income of $112,981 to 69% on an income of $726,308 (in 2013 dollars). At the time, the majority of the costs of drilling a typical onshore well were intangible drilling costs (IDCs). A combination of the large amount of IDCs, their tax treatment, and high income tax rates drove the appeal of these partnerships.

Investors' appetite for these structures waned with declining oil and gas prices and the upstream industry entered a prolonged downturn beginning in 1982. E&P companies with inflated debt burdens from the influx of capital from the late 1970s and early 1980s created massive losses for their lenders. One of the early and most significant events of this period was the failure of the Penn Square Bank and the effects of its failure on numerous other banks.

Penn Square Bank was declared insolvent on July 5, 1982. Penn Square had about 80% of its loan portfolio in oil and gas loans and had sold more than $2 billion in participations to several other large banks. Penn Square had grown its oil and gas lending from around $30 million in assets in 1975 to $525 million in assets at the time of closure.

Penn Square failed due to a combination of the poor credit quality of its loan portfolio and a funding crisis. An unusually large number of Penn Square loans were not secured by proved producing reserves but instead secured by undrilled oil and gas leases, representing unproved resources rather than reserves. The funding problems emerged as Penn Square had utilized large, short-term certificates of deposits issued to other institutions for funding together with local retail depositors. As oil prices began slipping in 1982, the institutional funding came under pressure. As word spread locally that numerous FDIC bank examiners were working in the Penn Square offices, retail funding came under pressure. Shortly thereafter, there were lines of depositors outside the bank seeking withdrawals.

Continental Illinois subsequently had to write-off more than $500 million in loans it purchased from Penn Square and eventually failed itself. Additionally there were major loan losses at numerous other banks, including Seattle First, Michigan National Bank, and Chase Manhattan Bank.

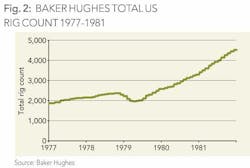

The industry downturn assumed grave proportions with the major crude oil price collapse of 1986. Oil prices dropped from a high of $36.83/bbl in 1980 to $14.43/bbl in 1986, essentially erasing the oil price gains precipitated by Iranian revolution in 1979. See Fig 3.

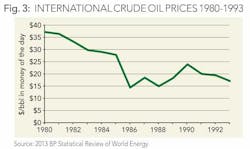

As a result of Penn Square and falling oil prices, bank credit and other public and private sources of capital for the industry dried up and the rig count dropped from a high of 4,520 rigs at the end of 1981 to 900 rigs at the end of 1986. See Fig 4.

The capital markets also adjusted with a series of restructurings, mergers and acquisitions, asset sales, and growth in new forms of capital.

During this downturn, participants in the capital markets began to lay the groundwork for the creation of the vastly improved markets we have today. Through the late 1980s and 1990s the markets became: 1) more institutional, 2) more linked to the public markets, and 3) more sophisticated.

By the early 1980s, the industry had created hundreds of drilling partnerships, mostly held by retail and high net worth investors. When sold to these investors, each partnership had a set amount of capital to drill wells. Many were leveraged with bank debt. As private partnerships with a fixed amount of initial capital, secondary offerings were not available. In addition, investors also suffered from holding an illiquid limited partnership interest.

Given these weaknesses, oil and gas executives and investment bankers went to work and began a consolidation process. The structure most often used was what was termed a "roll-up" into a new C-corp or a new master limited partnership (MLP). In this process, the limited partners (LPs) would contribute their LP interests to the C-corp or MLP in exchange for common stock or MLP units. In turn the E&P company that had formed the partnership as the general partner (GP) would exchange its GP interest for units in the new entity. Then, the C-corp or MLP would register with the SEC and become a publicly traded entity.

Thus, formerly private, predominately retail capital structures were transformed into 1) entities that could access public markets through secondary offerings, and 2) liquid securities that could be traded in the public markets.

Additional sophistication entered the E&P capital markets with the introduction of the futures market for crude oil in March 1983. This market experienced strong growth and attracted a broader range of participants to the energy markets. This eventually spurred banks and institutions to create over-the-counter markets that offered not only crude oil futures, but natural gas futures, futures options, swap contracts, and other derivative products covering a broad range of energy products, including diesel, fuel oil, gasoil, heating oil, and unleaded gasoline.

During the mid and late 1980s, mezzanine financing began to enter the E&P market and served to partially fill the void of traditional bank financing. Mezzanine funds were attracted to the E&P market as the lack of traditional bank loans allowed the mezzanine funds to price their product at attractive rates of return while also enjoying, generally, a senior secured position in the capital structure. Being a semi-surrogate for traditional bank lending, mezzanine funding typically had a high component of proved producing reserves in the asset mix. As the amount of mezzanine funding grew, so did the institutional component of the E&P capital markets.

During the 1990s, two more sources of capital grew in the E&P capital markets: institutional private equity and high yield bonds. Institutional private equity was attracted to the E&P market for several reasons. First, as commodity prices increased, so did the economics. Second, many of the sponsors of mezzanine funds incorporated institutional private equity into their business model to provide capital for transactions with a higher component of drilling risk and less of a proved producing component that might otherwise be funded by mezzanine financing. Third, institutional private equity as an asset class experienced strong growth and needed capital intensive sectors such as E&P as investment options.

As for high yield, the E&P sector sat on the bench during the high yield boom of the 1980s due to depressed oil and gas prices and poor economics. Global macroeconomic indicators were beginning to reflect pent-up demand for petroleum in the emerging markets and as a result high yield investors adopted a favorable view of oil and gas exposure. As returns and rig counts began to climb in the late 1990s and early 2000s, high yield bonds became an important part of the E&P capital markets. E&P companies were attracted to the longer dated maturities and relaxed covenants as compared to traditional bank loans. In addition, similar to institutional private equity, high yield as an asset class experienced strong growth and needed additional sectors to diversify the asset pool. See Fig 5.

Again these new and growing asset classes have expanded the options, the size, the sophistication, and the institutional aspect of the E&P capital markets. Also during this period commodity prices began to increase, which increased the interest of traditional lenders, and the bank loan market began to improve.

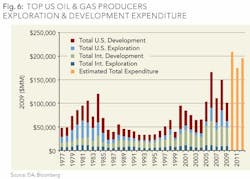

All of these improvements in scope, size, and sophistication set the stage for the 21st century and the beginnings of the shale era in the industry. And the E&P capital markets needed all of these elements to deal with the capital requirements of the shale era. As shown in Fig. 6, this new source of E&P activity presented a meaningful increase in the industry's appetite for capital.

The hard learned lessons during multiple commodity price cycles over the past 40 years since the Arab Oil Embargo have provided the impetus for both the technological and financial innovation in the oil and gas industry. The effect has been a reduction in OPEC imports as a percentage US oil demand from a high of 30.5% in 1978 and 1979 to just 20.0% in year-to-date 2013. See Fig 7. The successful partnership of the geosciences and the professionals in the capital markets have produced an extremely encouraging trend toward even less dependence and have reduced OPEC's influence on the energy needs of the US economy.

About the authors

John White serves as a research analyst and is also responsible for business development at Triple Double Advisors. Prior to joining Triple Double, he was an energy equity analyst with Natixis Bleichroeder and Next Generation Equity Research. From 1996 to 2003, he served as an energy high yield analyst for BMO Capital and John S. Herold Inc. White's experience includes banking and credit analysis responsibilities with Scotia Capital. His industry background includes working in acquisitions and divestitures and exploration and production, primarily with BP. He is active in a number of petroleum industry associations including the Independent Petroleum Association of America and Houston Producers' Forum. He received a BBA from the University of Oklahoma and an MBA from the University of St. Thomas (Houston).

Gabriel Chavez is responsible for analyzing exploration and production equities and trading. Prior to joining Triple Double, he was a research analyst at Koch Quantitative Trading where he developed systematic equity trading strategies. From 2000 to 2004, he was an analyst at Enron Corp. where he advised on acquisitions, financings, and divestitures in various energy sub-sectors. Chavez received a BS in economics from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania with dual concentrations in finance and management. He is a candidate for a MA in philosophy from the University of Houston and the working title for his thesis is "Adam Smith and the Ethical Foundations of Free Market Economics."