Clean air, clean technology take hold in South Texas

BEXAR COUNTY, Tex.—Increased production and economic stimulus are two of the most talked about outcomes emanating from South Texas' Eagle Ford shale. Given the arid region, water management has become a top priority for both operating companies and community stakeholders. In states where drilling activity is a fairly new commodity, hydraulic fracturing garners most of the attention. In the rapidly developing South Texas Eagle Ford, air quality is on the minds of both regulators and companies working the play.

The Environmentally Friendly Drilling (EFD) Systems, an institution that actively researches technology solutions to environmental issues relating to unconventional resource development, recently held a symposium in San Antonio, Tex., to analyze the current state of technology integration involving decreasing the industry's footprint by lowering emissions factors in field development activities.

Several panels included service and supply companies, operating companies, and speakers from local government and environmental groups.

Clearing the air

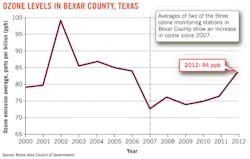

Unlike Dallas or Houston, San Antonio was, for some time, the largest city in the US that had not violated the Environmental Protection Agency's ozone rules under the Clean Air Act. The city lost this distinction on Aug. 21, 2012, when two ozone monitors in Bexar County registered ozone levels above the federal limits.

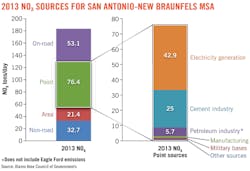

Bexar County is the center of the San Antonio-New Braunfels Metropolitan Statistical Area (SA-NB MSA), which covers eight counties including Bandera, Kendall, Comal, Guadalupe, Medina, Wilson, and Atascosa. This region is equally bound to adhere to the EPA's ruling regarding ozone levels and non-attainment. At the time, high ozone events in the SA-NB MSA were unusual. Major sources for the region include on-road traffic, electric generation plants, the cement industry, and the petroleum industry; although, air quality can shift dramatically due to other nonlocal sources. "Smog and smoke from distant sources such as coal-burning power plants in the Tennessee and Ohio valleys and distant fires in Mexico can effect ozone levels," according to Peter Bella, Director of Natural Resources at the Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG).

In some cases, if smoke and pollution from outside the country have impacted ozone measurements, local governments can appeal a violation with the EPA.* In San Antonio's case, the local government is taking a proactive response. "Ozone levels for Bexar County have been going up since 2007," Bella said. As federal standards have become more stringent, there is some uncertainty as to if, or when, the region may be classified as a nonattainment area. The EPA refreshed its ozone requirement in 2008 from 85 parts per billion (ppb) to 75 ppb. Each MSA has to maintain a 3-year average of less than 76 ppb of ozone to remain in compliance with the Clean Air Act. The EPA is slated to refresh its requirement this year, which could reduce attainment levels even further.

Under the Clean Air Act, EPA regulates levels of ozone in the air and emissions of two of its precursors, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and oxides of nitrogen (NOx). "In San Antonio, we need to reduce NOx to bring our ozone levels down," Bella said. The region contains more VOC in its local airshed than it has NOx to react with it. "This means you can add more VOC, or take away VOC, and it really doesn't change the final ozone concentrations," he explained. It also means that a reduction in NOx equates to a reduction in ozone. For this reason, the SA-NB MSA is considered a "NOx-limited" region. Limiting local NOx levels will help limit local ozone levels.

"Impacts from remote sources on local air quality are very real," Bella added. "How much is Eagle Ford activity adding to our local ozone levels? The answer is, ‘We don't know.'" The newness of the Eagle Ford work makes it difficult to account for in terms of emission factors.

Taking inventory

Following the August violation, the AACOG set out to coordinate efforts with local communities, research organizations, and industry partners to begin taking stock in real emissions factors for the SA-NB MSA and in the Eagle Ford shale.

Karnes County resides just south of SA-NB MSA and shares its border with Wilson County. While it is not considered by the EPA as part of the SA-NB MSA, it is one of the highest producing counties currently in the Eagle Ford shale. The Texas Railroad Commission approved 824 drilling permits in the county in 2012, and in 2013 to date, 351 drilling permits have been approved in Karnes County alone. As of June 21, 2013, the active rig count for the Eagle Ford shale hovered at about 260 rigs. In January, Karnes County was the top oil producer in Texas, with nearly 2.9 million bbl of oil, according to the University of Texas San Antonio's Eagle Ford Impact report published in March.

San Antonio has a couple of options. Pending the EPA's refresh, the limit for attainment could be raised, although historically that limit has been decreased or has remained unchanged. Or, the SA-NB MSA could be expanded to include additional neighboring counties, but the limit of less than 76 ppb would remain. In either of these cases, Peter Bella along with the AACOG is actively working with the industry to develop an efficient, accurate inventory of Eagle Ford drilling and completions activities' contribution to air quality problems in South Texas.

Susan Stuver is a research scientist with the Texas Water Resource Institute, Texas A&M, working with both EDF and AACOG on the current emissions inventory. Looking ahead, much of the research is focused on real reductions brought forth by technology integration currently taking place in many unconventional operations, namely the increased use of natural gas as a power source for drilling and completions equipment. Displacing diesel in field operations is a solid path to reducing overall NOx emitted during drilling and completions activities. "We are working toward determining how much emissions are lowered when operators and drilling companies begin powering with natural gas, and by what factors," Stuver said.

There has been much debate about the limitations of natural gas as a "green" fuel source overall with some researchers pointing to the NOx generated during the development phase. Methane leakage and flaring also increase emissions of greenhouse gases, a separate issue. (See "Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations," Howarth et al, Cornell University.)

While that debate is much larger, Peter Bella and his constituents are working to gain facts. "It's important to get these right," Stuver said. "Overestimating the emissions generated from Eagle Ford shale development could possibly incur unrealistic regulations over time," she said. Once regulations are in place, they are rarely repealed.

Non-attainment

The real driver for the AACOG's commitment to working with the industry is to not only address emissions of ozone precursors, but also to coordinate among regulators and industry participants to begin a dialog about measures the industry has already taken to decrease its environmental footprint. According to Bella, a joint effort between the industry and those that regulate it is the best solution.

Should the SA-NB MSA find itself in a non-attainment status, businesses can face additional regulations, including required installation of clean technologies on new industrial development. In severe cases, cities also can face cuts in highway funding. With San Antonio serving as the gateway to the Eagle Ford, a joint effort with the oil and gas industry is a positive step to help the SA-NB MSA determine how to move forward and avert a step into non-attainment.

"To manage air quality, and ozone in particular, we have to talk about managing the sources of ozone precursors," Bella said. However, he describes air quality as a big stew. "There's [an ongoing] conversation about which sources impact our local ozone readings, and where they are located—in or outside of our region."

With the Eagle Ford, Bella is looking at best practices to develop the shale as clean as it can possibly be. Drilling and completions are generally powered by diesel engines. "All the diesel-powered equipment out there represents the potential for produced NOx," Bella said. "So one of our major goals now is to complete an emissions inventory." Understanding the engines, duty cycles, fuel sources, and load factors for a typical Eagle Ford well site will ultimately provide accurate estimations for what the impact is on ozone in the San Antonio region. "That's one of our major goals for right now," Bella said.

Technology solutions

As part of its mission, the EFD, which is managed by the Houston Advanced Research Center (HARC), facilitates research programs for new, low-impact technologies that reduce the footprint of drilling activities. The symposium held by the organization featured a number of suppliers who currently have bi-fuel systems working in the field that can burn up to 60% natural gas, displacing diesel as the primary fuel. Turbine technology also has been adopted by some operators, and these systems can use 100% natural gas. The systems were initially adopted in shale operations as a means of powering drilling equipment but have another use powering pumping equipment during fracing operations.

Apache Corp., along with several other operators, has actively pursued natural gas options for powering drilling operations. In January 2013, Apache became the first operator to frac a well using natural gas as the power source.

"Our rationale is clear," said Elle Seybold, Global Gas Monetization, Apache. "The economics around using natural gas as opposed to diesel is very compelling." The company estimates the industry used more than 700 million gal of diesel for fracing operations in 2012. At an average cost of $3.40/gal, that equates to $2.38 billion spent on diesel fuel alone. With average substitution rates of 50% to 60%, displacing diesel with natural gas may dramatically reduce operating costs as the technology now being deployed is proven. Operating rigs and pumping equipment with natural gas from the field could further reduce US imports by 17 million bbl, the company said.

Bi-fuel systems, while in use in many unconventional resource plays, have not fully penetrated the market. In December 2012, Apache estimates that a mere 1% of the drilling fleet was operating with bi-fuel systems.

Sourcing fuel

According to Seybold, Apache has tested most of the available options for fracing with natural gas as the power source. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), compressed natural gas (CNG), and field gas are three conduits by which these systems can be deployed. "LNG is a viable solution for large applications," she said. LNG's consistency and density make it an easy choice, but economic margins are somewhat lower due to conversion costs and equipment rental as compared to the use of field gas. Variations in diesel prices can also affect savings. In addition, supply problems can arise as it is difficult to predict the volume of LNG needed every day because substitution rates can vary.

"CNG is more cost-effective when it's closer to source," Seybold said. The company has fraced 20 wells using CNG with bi-fuel generators. Seybold said the potential exists for up to 60% substitution, but lack of access to a high-fill station has limited progress thus far.

"Anywhere you are developing natural gas, you potentially have an unlimited fuel supply when using field gas," she said. The company has been using bi-fuel field gas fueled systems for several of its drilling operations, but this process is not without risk. Gas quality can affect drilling performance. Pressure drops and inconsistencies in the gas make-up can lower performance. Also, Seybold made the distinction between using sales gas and wellhead gas as the former is cleaner and can be accessed with no royalty issues. "It's a better way to go," Seybold said.

"Adopting natural gas as a fuel source in the field is manageable, but it does require learning," she continued. "In another year, the next adopters are going to have a much easier time." In general, bi-fuel systems provide some flexibility over dedicated (100% natural gas fuelled) engines or turbines, but strong conversion economics are needed to drive this transition. While economic margins are favorable for natural gas, Seybold believes that every part of the value chain will have to see the savings to make bi-fuel, dedicated, and turbine technology standard. "We are pushing that envelope pretty close as an operator," Seybold said. "Apache is committed to continuing its trials; we do see benefits, and we would like to figure this out."

Economic environments

While economics is currently driving this transition, the environmental impact is not lost on the industry. "The environmental benefits of powering field operations with natural gas are significant," Seybold said. The company also is attracted to the abundance of domestic supply. "‘Made in America' is [a brand] that Apache is proud of," she said.

From an emissions standpoint, ultimate adoption of bi-fuel systems and 100% natural gas systems will come down to economics at the end of the current trend. According to Steven Smeltzer, Environmental Manager, AACOG, EPA mandates will call for all diesel-generated oilfield equipment to be classified as Tier IV, which is currently the lowest emission standard for combustion motors. While the AACOG as well as operating and service companies currently developing shale plays like the Eagle Ford consider new technology to lower emission rates across the board, price competition between diesel and natural gas may ultimately decide which systems become dominant in the field.

In San Antonio, coordinated efforts are ensuring the best possible outcome for both an industry that is booming and local communities that are experiencing economic benefits as a direct result. "If it is true that the Eagle Ford shale development could be part of our ozone problem, our goal is to help them be part of the solution," Bella said. "It's an easier sell to local elected officials who are involved in local air quality planning."

References

*There are two avenues for data disputes in attainment settings under the Clean Air Act.

1. The so-called "Exceptional Events" policy, written (among other objectives) to allow the exclusion of data showing elevated pollution levels when research reveals the influence of pollution sources which the EPA considers beyond reasonable control. See the EPA's "Treatment of Data Influenced by Exceptional Events" site: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/analysis/exevents.htm.

2. Part D - Plan Requirements for Nonattainment Areas of the federal Clean Air Act contains subpart 179B, "International border areas," (http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/7509a: referenced as 42 USC § 7509a) which states,

(b) Attainment of ozone levels: Notwithstanding any other provision of law, any State that establishes to the satisfaction of the Administrator that, with respect to an ozone nonattainment area in such State, such State would have attained the national ambient air quality standard for ozone by the applicable attainment date, but for emissions emanating from outside of the United States, shall not be subject to the provisions of section 7511 (a)(2) or (5) of this title or section 7511d of this title.

So, if a region which would be considered nonattainment can demonstrate that pollution from outside the country is the reason they would be so considered, that region can be excused.

See also EPA's "Guidance on Assessing the Impacts of May 1998 Mexican Fires on Ozone Levels in the United States," dated November 10, 1998: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/naaqs/ozone/ozonetech/mexfires.htm, in which this policy was applied.