Pakistan's gas discoveries eliminate import need

This article is based on a FACTS advisory released in July 2001, which was updated this month exclusively for Oil & Gas Journal.

Pakistan has substantial natural gas reserves and a current reserves-production (R/P) ratio of 31 years. The base-case scenario for natural gas consumption reveals that, with no new discoveries, these reserves can meet demand for the next 18 years.

Furthermore, the country enjoys a respectable success rate for natural gas exploration, and with the right policies in place, domestic reserves can be developed to fulfill the incremental gas demand.

The country's energy sector, particularly power generation, is heavily dependent on fuel oil. This dependence is seen as undesirable, because it is difficult for the already strained economy to bear the load of a rising fuel oil import bill, which has now reached $1 billion/year.

Natural gas is therefore the preferred option, and the government is pursuing a policy of substituting fuel oil with natural gas for electricity generation.

This article analyzes the general natural gas situation in Pakistan, focusing on its projected use, particularly in power generation. We forecast that a real annual gross domestic product growth rate of 4% warrants an annual increase of 5% in power generation, and with a moderate fuel substitution policy, natural gas consumption for power will grow at 8%/year. This translates into overall natural gas consumption growth of 6%/year.

Eco-political changes

The new discoveries in Pakistan have eliminated the need for gas imports via pipeline for some time to come. This has changed the geopolitical landscape in the subcontinent. On the one hand, Pakistan's role as a potential pipeline transit route is no longer related to its own internal needs. On the other hand, the assurances provided by the suppliers that, if Pakistan ever interfered with supplies to India, she would lose her own supplies too, has lost its political appeal.

For now, Pakistan can continue to develop its domestic reserves. The country may also find it preferable to explore the LNG import option, rather than pipelines, to complement domestic production or to supply possible shortages in the future.

Pakistan's economy has experienced increased turbulence in recent years. Before the economy could recover from the effects of post-nuclear test sanctions, it underwent another shock-the military coup. The military regime embarked on a drive to uproot corruption and undertake the process of enforcing proper documentation of the economy for taxation purposes.

Recent events-the war in Afghan- istan and the India-Pakistan tensions-add further uncertainty, and it is too soon to determine the impact of these events on Pakistan's economy.

Removal of certain sanctions, increased financial assistance from developed countries, and the indication of European markets opening up for Pakistani exports will have a positive impact on the country's economy. On the other hand, however, factors such as increased war-risk insurance charges on Pakistani imports and exports have hurt it.

For the 2000-01 fiscal year, the agriculture-dependent economy experienced an unimpressive GDP growth of 2.6% because a negative growth of 2.5% in the agriculture sector counteracted part of the manufacturing sector's growth of over 7%. For the current fiscal year, the GDP estimate stands at 2.5%. However, in the energy sector, oil and gas consumption registered healthy growth rates.

Oil and gas

Oil consumption increased by almost 9%, and gas consumption went up by 12%. The government is conscious of the importance of the energy sector in ensuring economic growth and has therefore placed energy as one of the priority issues in its current economic plans.

The government has offered a number of incentives to bolster investor interest in the country's oil and gas sector. The country is gradually privatizing key oil, gas, and power companies and deregulating the oil and gas sector. Oil and gas prices are in the process of being deregulated, with a move towards the reduction of subsidies.

Privatization of state utilities will follow deregulation, beginning with Sui Southern Gas (SSG) and Sui Northern Gas (SNG), the gas distribution companies, then Pakistan State Oil, the state monopoly on refined products imports, and finally the Water and Power Development Authority.

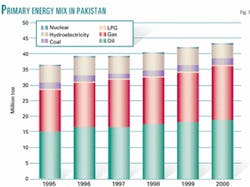

Natural gas has played a significant role in Pakistan's primary energy mix. It holds a share of almost 40% of the total primary energy consumption (Fig. 1). Oil holds the biggest share with 45%. Coal, hydro, and nuclear energy account for the balance.

Pakistan has significant natural gas reserves. They currently stand at 24.9 tcf, and, with the current level of consumption-production is 2.169 bscfd-these reserves will last for about 31 years.

Gas discovery in the country dates back to the 1950s when Oil & Gas Development Corp. (OGDC) of Pakistan, with the help of some international partners, discovered natural gas in Sui field. This is Pakistan's largest field, with a current production of 650 MMscfd.

Major natural gas producers in the country are state-owned Pakistan Petroleum Ltd. (PPL), OGDC, and Mari Gas Co. Ltd. (MGCL). Together, they account for almost 85% of total production (Fig. 2).

Sectoral gas usage

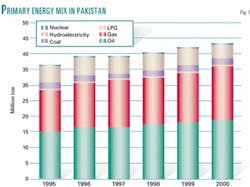

Pakistan natural gas consumption has experienced an average annual growth rate (AAGR) of 5.5% in the 1995-2000 period. Currently the largest sector of natural gas consumption in Pakistan is power generation, which accounts for almost one third of total consumption (Table 1).

Natural gas use in power generation has grown at an AAGR of almost 5% in the last 5 years. This growth is expected to accelerate, because power generation is expected to be the main driver of natural gas consumption in years to come.

The fertilizer sector accounts for almost one fourth of total consumption, this includes gas used as fuel and feed stock. Residential use of natural gas has grown at a rapid rate of 7.6% annually during 1995-2000. This is supplemented by expansion of the distribution network, which increased to 61,002 km in 2000 from 43,500 km in 1995.

Furthermore, work has recently commenced on a project that will increase the gas transmission capacity of SNG by more than 400 MMscfd to 1.4 bscfd. The project involves setting up the transmission infrastructure for transporting gas from Sui gas field to the northern and central regions of the country and will be completed by first quarter 2004. It is aimed at supplying gas for residential consumers and independent power producers (IPPs).

The government has been actively pursuing natural gas substitution for oil products, notably natural gas in power generation and compressed natural gas (CNG) in the transport sector.

Currently there are about 160 CNG stations in the country, and plans are in place for another 150. CNG consumption in the country is expected to grow rapidly, especially as CNG use provides considerable savings over gasoline.

In order to facilitate natural gas use in the industrial sector, SSG has recently commenced the construction of an LPG extraction plant at Badin gas field. It is estimated that this plant will produce 4,600 b/d of LPG. The project is scheduled for completion by the end of 2003. The recent trend of natural gas consumption in various sectors is shown in Fig. 3.

Gas in power generation

Although the power generation sector is the largest consumer of natural gas (Fig. 3), and power generated from natural gas accounts for about one third of Pakistan's total power generation (Fig. 4), fuel oil recently has increased its role in power generation. In 1980, the contribution of fuel oil to power generation was negligible; however it increased to almost 40% in 2000.

This rapid increase in the consumption of fuel oil is attributed to the opening of the power sector to private investment in 1997. This led to the addition of over 3,000 Mw of thermal capacity by IPPs in 1997, increasing to 5,500 Mw in 2000, taking the total generating capacity of the country to over 17 Gw.

The decision to use fuel oil for power was supported by lower oil prices in 1998. However, rebounding prices have made fuel oil use highly undesirable. Because the country has to spend valuable foreign exchange for the import of fuel oil, the import bill for fuel oil in the current fiscal year stands at $1 billion.

Pakistan currently imports two thirds of its total requirement of fuel oil, and at the projected consumption rate, is poised to become one of the largest importers of fuel oil in the Asia-Pacific region by 2005.

This has led to a drive to substitute natural gas for fuel oil in the power sector. Estimations reveal that, at the current level of power generation, over 800 MMscfd of additional gas is required to replace fuel oil in all the thermal power plants. This is higher than the current level of production, and therefore, any conversion plan will have to be gradual.

One such move has been made by the 1,300 Mw independent power plant Hubco, which has recently initiated a plan to acquire 220 MMscfd of gas from Bhit gas field by the end of 2002. Such an arrangement will result in savings of 35,000 b/d of fuel oil.

This decision was further facilitated by a standoff between IPPs and the previous government of Pakistan, which demanded rates to be reduced to 4.5¢/kw-hr from 6.5¢/kw-hr. The parties finally reached a compromise by the end of 2000 for 5.6¢/kw-hr.

Furthermore, on the basis of heat content, indigenously produced natural gas is considerably cheaper than fuel oil. In 2000 the fuel oil price in the domestic market was about $4/MMbtu, whereas the price of natural gas (at the industrial rate) was about $2/MMbtu. This gap might close in the future, however, as natural gas prices are deregulated.

Demand outlook

The government has targeted a GDP growth rate of 4.5% for the next 3 years and estimates that natural gas consumption will increase 50% by 2006. Given the importance of gas use in the power sector, it is necessary to have a reasonable forecast of power generation.

Based on our model, we estimate that a long-term real GDP growth of 4% warrants an increase in power generation of 5% annually. Table 2 lists these scenarios. Furthermore, it is assumed that additions in hydro and nuclear power generation will be only marginal.

Given these assumptions and a moderate substitution drive for fuel oil, a potential growth of 8% for natural gas in power generation is indicated.

The low-case scenario assumes a slow growth rate of 2% in real GDP and slow-paced substitution of fuel oil. This results in an AAGR of 1% for natural gas use in power generation.

The high-case scenario assumes real GDP to grow at 6% and an aggressive drive for fuel oil substitution, yielding an AAGR of 13% for natural gas use in power generation.

Another factor that will play into the consumption of gas for power generation is the future role of coal in the power sector. Pakistan has sizable coal reserves-estimated at 3 billion tonnes.

Current consumption of coal stands at 3.2 million tonnes/year, of which only 8% is used for power generation.

There is, therefore, potential for significant growth of coal consumption for power generation, which might displace oil and possibly natural gas to some extent in the future.

Adding in other sectors of natural gas use, total long-term growth in consumption will range from 2.8% (the low case) to 8.9% (the high case). The base case estimates an AAGR of 6.2%. These scenarios are presented in Fig. 5.

Supply outlook

According to the base-case forecast, even with no new gas discoveries and no imports into the country, the current level of reserves is likely to last until 2018. Given a high rate of consumption, the reserves will deplete by 2015, and a slow growth rate, estimated by the low-case scenario, shows the current level of reserves will last until 2024.

Such a demand situation, coupled with a respectable success rate for domestic gas discoveries, implies that there is no urgency for Pakistan to import gas.

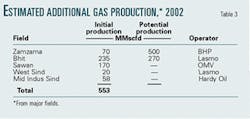

Because of Pakistan's higher than average success rate for gas discoveries, its proven reserves have grown at almost 2%/year during the last 10 years. In recent years international oil and gas companies have registered several discoveries of gas reserves.

For example, Lasmo PLC, now part of ENI SPA, is operating two major fields with an estimated combined production of 255 MMscfd. Similarly, the 2 tcf Zamzama field operated by BHP Billiton Ltd. has the potential of producing 500 MMscfd (Table 3).

On the whole, the government estimates that about 1bscfd of natural gas will be added by new finds.

Pipelines vs. LNG

So far, Pakistan's efforts to import gas via pipelines have not been too successful. In 2000 the government agreed on a Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline. Such an option has economic advantages for all involved parties. For Pakistan it would translate into revenues in the form of transit fees, $600 million/year, and an option to purchase gas from the pipeline.

For India and Iran, it is advantageous because it is the most economical means of transporting gas. However, on political grounds, given the ongoing tensions between India and Pakistan, such a project is unlikely to become a reality. The recent strain between India and Pakistan, which has led to a war-like situation, underscores the importance of resolving political issues between the two countries before any such arrangement can work out.

Another import option is a pipeline from Turkmenistan passing through Afghanistan. This project ran into trouble when Unocal Corp., the major international company involved, decided to pull out in 1998. Since then, the governments of Pakistan and Turkmenistan have had intermittent dialogues with the Afghan authorities; however, none of the efforts has been promising. As a result, this project is even less likely to materialize.

Afghanistan is currently in a state of war and nation-building, and therefore it is too soon to foresee how things will settle in the long run.

It can be argued that a pro-US re- gime in Afghanistan will be conducive to the involvement of a US firm in the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan pipeline.

A third option is to link Pakistan to the Dolphin project that will supply gas from Qatar to UAE and Oman. Pakistan can be added to the project by means of a subsea pipeline from Oman. In fact, Pakistan initially had signed an agreement to buy gas from the project; however, the Oman-Pakistan phase remains questionable.

Pakistan's respectable track record for gas discoveries and the possibility of a sluggish growth in demand makes the feasibility of gas imports doubtful. Furthermore, it can be argued that imports in the form of LNG, particularly spot LNG, might be preferable over a gas pipeline. As such, LNG contracts provide flexibility both in terms of volume and source.

While pipeline imports are certainly more cost-effective, pipelines require a large import volume, which cannot be justified by Pakistani demand until long into the future.

It is worth noting that Pakistan is in close proximity to its potential gas suppliers, i.e., the Middle East (Qatar and Iran) and Central Asia (Turkmenistan). However, LNG use is economically competitive with pipelines only at distances greater than 3,000-6,000 km. Therefore, the option to import gas via LNG will be more costly, both in the investment and delivery costs of imported gas.

Estimation reveals that if natural gas consumption grows at 6.2%/year (base case), reserves increase at 2%/year, and the R/P ratio is held fixed at the current level; then by 2005 the country's cumulative demand for LNG will exceed 3 million tonnes, which is large enough for one train of LNG.

In a nutshell, it is difficult to justify the viability of a pipeline to furnish Pakistan's demand exclusively. However, there is a bigger incentive in economic terms to use Pakistan as a transit route for a gas pipeline to its neighbor India.

Political and security concerns keep such an arrangement from materializing, and therefore in the short run, it makes more sense for Pakistan to aggressively develop its domestic reserves and remove the need for imports indefinitely.

Reforms

The energy sector's deregulation is imperative to the viability of investments in the gas sector. Domestic prices of natural gas and petroleum products have traditionally been regulated in Pakistan, while investors are of the view that the energy sector should be free from all price regulations.

The government, in its 1994 petroleum policy, offered indexing of domestic gas prices to international oil prices. However, it became difficult to uphold this policy when oil prices increased by almost 33% in 1996 from the 1994 level. This policy was therefore amended so that increments in the gas price were reduced as the international price of oil exceeded $16/ bbl.

This change in policy had a negative impact on the investment situation, because upstream expenditure dropped by 50% in 1999 from $300 million in 1996. In an effort to restore investor confidence, the current military regime has provided a major incentive, offering the guarantee that all of the gas that upstream companies supply will be purchased by the state gas transmission companies.

A significant step towards reform of the gas sector was the establishment of the Natural Gas Regulatory Authority (NGRA) in 2000. NGRA will be responsible for regulating tariffs, determining wellhead gas prices, and protecting consumer rights.

Recently the Asian Development Bank extended a grant of $1 million for a project that will lay down the foundation for reforms in the gas sector and ultimately privatization of the state gas companies.

Synopsis

Pakistan has a history of significant gas use and a respectable success rate for gas discoveries. At forecasted levels of gas consumption, the country's current reserves will last until 2018. Thus an import gas pipeline exclusively for Pakistan's own use is economically not viable. In the short term, Pakistan needs to continue developing its domestic reserves and explore the option of LNG imports for any incremental volumes.

Imperative to the viability of such a project is the process of deregulation and price decontrol. The government has undertaken this process, which is being watched closely by foreign investors.

The new supply-demand balance has important geopolitical implications. Although suppliers can no longer assure India of Pakistani noninterference with a pipeline, Pakistan seems to genuinely see herself as a transit route without feeling competitive with India for supplies from imports. How these two forces will work themselves out is not clear.

What is clear is that the geopolitical balance has shifted by the fact that Pakistan is no longer desperate to make an import project work to supply her own needs. This affords Pakistan more leverage in dealing with India and the gas suppliers. However, it is imperative that Pakistan and India resolve their political differences before they even start discussing the pipeline project.

The authors

Hassaan S. Vahidy holds an MA in economics from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and an MBA and a BS in engineering. He is currently a senior associate at FACTS Inc. and a researcher at the East-West Center in Honolulu, involved in downstream oil and gas research for the Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions. Prior to this position, Vahidy worked for Royal Dutch/Shell in Pakistan.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc. He was born in Iran and received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern studies. In the later 1970s, Fesharaki attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy advisor to the prime minister of Iran. In 1979 he joined the East-West Center where he currently is a senior fellow.