Turkmenistan faces challenges in export transportation options

This is the fourth and concluding part of a series on Turkmenistan's oil and gas exploration, production, production sharing, and transportation prospects.

Part 1 focused on the country's ambitious goal of significantly boosting oil and gas production by 2010 (OGJ, Oct. 14, 2002, p. 43). Part 2 described the production sharing agreements in progress with foreign operators, which are considered key elements in attaining the production goal (OGJ, Oct. 21, 2002, p. 49).

This fourth part is a discussion of the country's transportation infrastructure and expansion options.

Oil transportation

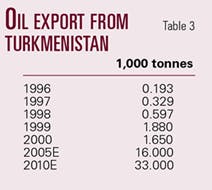

Oil from Turkmenistan is exported mainly by sea in two directions, by western and southern routes.

The western route, accounting for over half of all oil shipments, is used to deliver oil to the countries of the Black Sea and Mediterranean basins. The southern route involves oil to Iran and the Persian Gulf and consists of swap arrangements. Small amounts of oil are transported by rail or road to Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

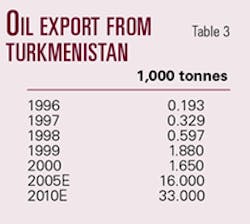

By raising oil production in the country, Turkmenistan plans to increase oil exports to 16 million tons/year (320,000 b/d) in 2005 and 33 million tons/year (660,000 b/d) in 2010 (Table 3). In the medium term, this goal implies construction or rehabilitation of export pipelines in addition to raising the capacity of marine terminals.

KTI oil pipeline

Transport of Turkmen oil to Iran and on to the Persian Gulf by the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran (KTI) pipeline is considered the most promising of all proposals. Some 550 km of this 2,500-km pipe are to be laid in Turkmen territory.

Capacity between 25 and 50 million tons/year (500,000-1 million b/d) of oil is under consideration. TotalFinaElf SA of France, which in 1998 was authorized by the Turkmen government to study the proposal, in May 1999 submitted to Ashgabat a preliminary feasibility study for the Turkmen section.

The document stated that the Turkmen section will not involve any technical difficulties that may hold back implementation. TotalFinaElf has been signaling its growing interest in implementing the project.

The French company gives preference to the Iranian route due to a high pricetag on the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, whose preliminary cost was estimated at $3 billion, while the KTI oil pipeline will cost around $1 billion. As Iran's Ambassador Mortez Safari said last June in Astana, Iran "is ready to begin negotiations on a giant project of building an oil pipeline from Kazakhstan to the Persian Gulf via Turkmenistan."

Other oil pipelines

Plans to use the existing Omsk-Shymkent-Seidi oil pipeline that is out of service are also considered.

Interestingly, discussions focus on extending the pipeline in different directions. In 1995 Unocal Corp. of the US proposed a Central Asian oil pipeline. The project called for extending the Omsk-Pavlodar-Shymkent-Turkmenabat (Seidi) oil pipeline that originates in Western Siberia to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and on to oil terminals on the Arabian Sea.

Preliminary estimates indicate that capacity of the 1,667-km pipe will be 50 million tons/year (1 million b/d) of oil and that cost will be $3 billion.

Unocal withdrew from the project in late 1998 due to instability in Afghanistan and associated risks. Now that the political situation in Afghanistan has changed for the better, Turkmenistan President Saparmurat Niyazov has proposed to revive the project.

The Russian oil transportation company Transneft floated another option for using the Omsk-Turkmenabat pipeline. It proposed to extend the pipeline to Iran. The project can be implemented by building a missing section of pipe between the oil transportation systems of Turkmenistan and Iran.

Using the Omsk-Tehran route, companies that produce oil in Western Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan would be able to deliver to northern Iran refiners under swap arrangements in which Iran would deliver like amounts of Iranian oil in the Persian Gulf.

Gas exports

Turkmenistan's main export product is natural gas.

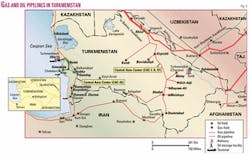

How much gas is produced and shipped for export each year depends on contracts with outside consumers that for the time being are limited to Ukraine, Russia, and Iran (Table 6).

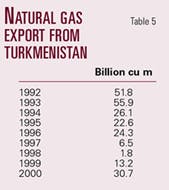

The trend during 1993-98 was declining gas exports. Since 1999 export has grown steadily (Table 5). The figure for 2001 is 37.3 billion cu m/year (3.6 bcfd).

The shares of export in Turkmenistan's commodity export structure in 2001 were gas 57%, petroleum products 14%, and oil 12%. On the other hand, as oil production and refining have been on the rise in the past several years, so have exports of oil and petroleum products (Tables 3 and 4).

The Turkmenistan (Deryalik)-Europe system (formerly known as the Central Asia-Center I, II, IV) is the main export gas pipeline (Fig. 3). In operation for many years, it is quite worn out. For that reason its capacity stands at 60 billion cu m/year (2.1 bcfd). Deliveries to Ukraine and Russia totaled around 33 billion cu m (1.1 bcfd) in 2001.

The Turkmenistan (Bekdash)-Europe gas pipeline (former Central Asia-Center III) can ship 5 billion cu m/year (484 MMcfd). As a result of reconstruction currently under way and planned, the capacity of the Deryalik-Europe pipeline is to climb by 2004 to 90 billion cu m/year (8.7 bcfd) of gas, while throughput of the Bekdash-Europe gas pipeline will be raised to 10 billion cu m/year (968 MMcfd).

The third export line, a 200-km system from Turkmenistan (Korpedzhe) to Iran (Kurtkui), was commissioned in 1997. Though its capacity stands at 8 billion cu m/year (773 MMcfd), a maximum 4 billion cu m/year (386 MMcfd) of gas is transported due to low gas demand in Iran's northern provinces.

Afghanistan-Pakistan

In an attempt to diversify deliveries of gas to world markets, Ashgabat will expand its gas export system in the coming 7-8 years.

Turkmenistan is taking active steps towards reviving the Trans-Afghan gas pipeline proposal, offering gas deliveries from Dauletabad, one of the largest fields in Turkmenistan, via the Afghan city of Kandahar to Multan, central Pakistan. A projected capacity of the 1,460-km pipeline with an estimated price tag of $2 billion is 30 billion cu m/year (2.9 bcfd) of gas.

An international consortium CentGaz led by Unocal was formed in the mid-1990s to implement the project, shelved after the Taliban rose to power in Afghanistan.

With positive change in Afghanistan, talks toward the Trans-Afghan project have resumed. In late May 2002, the presidents of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan signed in Islamabad an intergovernmental agreement for its construction. Turkmenistan set up a working group in June, and Afghanistan and Pakistan are to form similar working groups shortly.

Niyazov officially invited companies from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus to join the project. The government of Turkmenistan also called on international companies to contribute to the project by supplying equipment, materials, and technologies. Several Russian companies, such as Rosneftegazstroy, Gazprom, Itera, and Rosneft, indicated their interest in participating in the project, while international banking institutions were prepared to take part in construction financing.

Pipeline to China

Due to the 5,730-km distance to the Chinese coast at Shanghai and $9 billion cost, the Turkmenistan (Dauletabad)-China pipeline project stalled for a long time.

This envisaged construction of a 30 billion cu m/year (2.9 bcfd) gas pipeline eastward from Turkmenistan. However, Turkmenistan recently resumed negotiations with China, pinning its hopes on a new route.

China plans to complete construction of the Trans-China gas pipeline by 2005. It would originate in the Tarim basin in western China, and a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan can be linked to that system. Such linkage would cut the length of the Turkmenistan-China section to 1,500 km.

Another length- and cost-reducing option under consideration is to build a pipeline from gas fields on the right bank of the Amudarya River.

Trans-Caspian plans

The Trans-Caspian proposal calls for transporting gas from eastern Turkmenistan through a pipeline laid on the Caspian seabed to Azerbaijan and via Georgia to Turkey.

Projected capacity of the $3 billion pipeline is 30 billion cu m/year (2.9 bcfd). March 1999 saw the establishment of the Transcaspian Pipeline Consortium led by US company PSG, later joined by Shell. Shell took the lead after PSG pulled out.

The project remains in deadlock since 2000 after Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan failed to agree on the share of gas that Azerbaijan would be able to ship through the line.

On the other hand, Turkmenistan and Turkey have a long-term purchase and sale agreement that envisages the delivery of 16 billion cu m/year (1.5 bcfd) of gas.

As a Shell representative stated during the May roundtable in Ashgabat, the existence of this agreement gives hope that the project will be implemented and for that reason Shell remains committed it. The final decision that will determine its fate rests with the governments of participating countries, the Shell representative said.

Gas supply to Armenia

In the recent period Ashgabat has been taking steps towards launching yet another project of building a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to Armenia via Iran.

In August 2001 Iran supported the idea of transporting Turkmen gas to Armenia through its territory. The project also received backing from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, as well as from Gazprom and Itera that gave their preliminary approval to take part in the project.

The two companies own 45% and 10%, respectively, in JV Armrosgazprom, which will operate the pipeline. Several factors bode well for the project: the gas pipeline will not have to be long (just 140 km) and will cost only $120 million to build. Initial deliveries to Armenia totaling 1 billion cu m/year (97 MMcfd) are to be raised later to 3 billion cu m/year (290 MMcfd).

Keep on playing

The present-day geopolitical situation in the Central Asian region may help Turkmenistan promote some of its projects of shipping hydrocarbons to world markets.

For example, the Trans-Afghan project is increasingly supported in international quarters. Official US representatives in their most recent statements voiced support for the pipeline project. There is no doubt that Washington will benefit by a project that will provide access to world markets for Caspian hydrocarbons produced by many companies, including US corporations.

World Bank President James Wolfenson stressed the significance of the project for the economies of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Given the current situation, Russia, which would like to strengthen its influence in Central Asia and in Afghanistan, has no intention of watching the progress of the Trans-Afghan project as an onlooker. Negotiations between several Russian companies with Ashgabat, Kabul, and Islamabad clearly signal their willingness to join the project.

The search for new routes to access world markets by Russia and Kazakhstan also improves Turkmenistan's chances of implementing its export pipeline projects.

Kazakhstan's Gas Strategy for the Period of up to 2015 views Turkmenistan as a necessary partner in implementing a number of gas export projects via Russia to Europe, via Iran to Turkey, as well as in the eastern direction to China and Pakistan.

Besides, as oil production in Kazakhstan grows, the country will be stepping up transnational oil pipeline projects that among other things also envisage transportation of Turkmen oil. In its concept of Eurasian Gas Alliance, Russia, too, assigned Turkmenistan a key role in raising gas export to Europe.

Possible reanimation of at least some Turkmen export pipeline projects, as well as the objective of a comprehensive technological overhaul of the industry proclaimed by Ashgabat, add to the allure of Turkmenistan for international companies. Development of transportation infrastructure will heighten the attraction of production projects in the Turkmen sector of the Caspian Sea.

The drive to introduce new technologies and equipment, emphasized by Ashgabat as the principal vehicle of raising hydrocarbons production, opens up to suppliers Turkmenistan's services market worth several billion dollars.

Time will soon show to what extent Ashgabat will be able to capitalize on new prospects and opportunities that are taking shape.

Clearly, when it comes to technological innovation the process should not be too complicated, and success will be determined by bilateral agreements (buyer-seller).

Success in implementing transnational pipeline projects will depend on all involved parties' flexibility and the ability to accommodate the interests of many sides and countries.

Correction

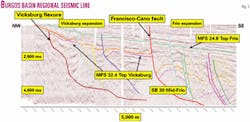

Fig. 3 incorrectly portrayed the seismic data in an article on Frio-Vicksburg exploration focus areas in Mexico's Burgos basin (OGJ, Sept. 23, 2002, p. 35). The figure now displays the seismic at the accurate orientation.