Oil pipelines played role in US invasion of Iraq

Gary Vogler

Howitzer Consulting LLC

Centreville, Va.

Politics influences the construction and operation of oil and gas pipelines. Given this, it may not surprise some pipeline veterans that the politics surrounding a few Middle East oil pipelines played a part in US motivations for the 2003 war in Iraq, launched Mar. 20 of that year. Contrary to my statements for more than 10 years in the press and on national television, there was an oil agenda for the Iraq war.

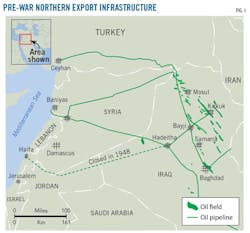

The three pipelines that played a role in the Iraq war included: the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline in Israel, the Kirkuk-Haifa pipeline originally constructed in 1934, and the Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline between Iraq and Syria, built in the early 1950s.

While researching my recently published book, ‘Iraq and the Politics of Oil,’ I asked a friend and retired Mobil Oil Middle East trader a simple question: “How would you move a cargo of oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean?” He replied that there were only two economical routes: the Suez Canal and the Sumed pipeline in Egypt.

Eilat to Ashkelon

There is, however, a third economical channel; a pipeline through Israel built in 1970. It was a joint-venture pipeline owned by Iran and Israel via the Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline Co. (EAPC) and established for transporting Iranian oil to Europe and Israel. Israel took sole control of EAPC in 1979 after the Iranian revolution. A Swiss court ruled in 2016 that Israel owed Iran $1.2 billion for its share of the pipeline.

EAPC has historically been a very secretive and important organization for the energy security of Israel. In late 2017 the Israeli Knesset passed a law ordering up to 15 years in prison for anyone leaking confidential company information.1 Israeli law states that releasing operational information about the activities of the company is an act of espionage.

This secret Israeli pipeline was a major source of Marc Rich’s fortune from 1970 through 1994. Rich was an oil trader pardoned by President Bill Clinton in 2001 for income tax evasion of $100 million. He owned and operated Marc Rich & Co. AG of Switzerland. The company’s name was changed to Glencore in 1995 and it is today the largest commodity trading company in the world.

Rich was described in his biography as a close friend of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency.2 Most of Rich’s fortune came from moving Iranian crude oil through the secret Israeli pipeline to customers in the Mediterranean. He moved this Iranian oil even after sanctions were imposed on Iran in 1979. Rich was able to supply Israel via this arrangement until the mid-1990s. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, US Vice President Richard Cheney’s chief of staff during the administration of President George H.W. Bush, was one of Rich’s lawyers for much of this time.

Glencore lost the Iran oil deal in the mid-90s after Marc Rich left the company, resulting in a sudden increase in Israeli crude price to above market rates. Israel’s minister of infrastructure said in early 2003 that the country was paying a 25% premium for its oil.3

How would the 2003 Iraq war provide relief? Via the Kirkuk-to-Haifa pipeline. Dr. Ahmed Chalabi made several promises to prominent and powerful members of the Israel lobby in Washington, DC, during the 1990s, including reopening this pipeline. In exchange, he wanted their help getting the US military to overthrow Saddam Hussein and install him as Iraq’s new leader.

The Iraq Petroleum Co. (IPC) built the Kirkuk-to-Haifa line in 1934. IPC’s owners included companies that became BP, Shell, Total SA, and ExxonMobil. The 12-in. OD line was the first built to export Kirkuk crude through what is today Iraq, Jordan, and Israel to the port of Haifa, a distance of more than 585 miles. The region surrounding its path was under British mandate at the time. The line operated from 1934 until 1948 when the king of Iraq ordered IPC to stop shipping oil to the newly created country of Israel.

The pipeline split at Haditha, Iraq, with the other branch running to Tripoli, Lebanon. Lebanon was under a French mandate at the time and this part of the line remained open after the pipeline to Haifa was shut.

Chalabi was an exiled Iraqi and adversary of Saddam. He was the leader of the Iraq National Congress (INC), an anti-Saddam political group that received millions of dollars of support from the US government during the 1990s. Chalabi also was closely linked to neoconservatives inside the Bush Administration and the Pentagon who pushed for his installment to lead Iraq after the removal of Saddam.

Three significant ways the Pentagon supported Chalabi and the oil agenda in 2003 were:

• Installing a secure voice communications link between Chalabi in Baghdad and the office of the vice president in Washington.

• Training and supporting Iraqi exiles (the Iraqi Freedom Fighters) to support Chalabi.

• Destruction of the Iraqi export pipeline through Syria.

In return for Pentagon support, Chalabi provided misleading intelligence reports to the US government. One of his more infamous sources of intelligence was an exiled Iraqi, code-named ‘Curveball.’ This Iraqi was interviewed in the UK press in February 2011 and admitted that he lied about biological warfare laboratories used by Saddam to produce lethal agents.4 He was an Iraqi chemical engineer who had defected to Germany in 1999. Secretary Colin Powell used this faulty intelligence to justify the Iraq war to the United Nations (UN) Security Council in February 2003, just before the invasion.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld publicly denied reports that the Pentagon supported any specific Iraqi to lead Iraq after Saddam’s removal, saying that the Iraqis would determine their own new leader. Despite Rumsfeld’s denials, those of us who worked at the Pentagon and later in Iraq realized that the neoconservative agenda included Chalabi leading a post-Saddam Iraq.

My first exposure to this fact was during a brainstorming session while engaged in prewar oil planning at the Pentagon as part of the war’s Energy Infrastructure Planning Group (EIPG). A small group of us were putting names on a board of possible candidates for the minister of oil in the new government. I personally felt the position had to be filled by an Iraqi, and the only name of prominence I had heard was Chalabi’s. When it was my turn to suggest a candidate, I wrote Chalabi’s name on the board. The young neoconservative assigned to our team, Mike Makovsky, went to the board and lined through Chalabi’s name. He said that there were bigger plans for Chalabi, he was to be prime minister after Saddam. There were several other instances of US government support for Chalabi, both leading up to and after the invasion.5

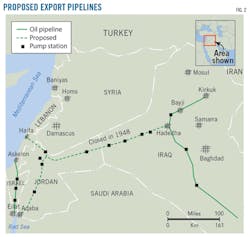

The Chalabi plan for opening the Kirkuk-Haifa pipeline included increasing its capacity to more than 1-million b/d, an effort that would cost billions of dollars but would carry more than $50-billion worth of oil through Haifa every year. The size of the expanded pipeline was to exceed 40-in. OD.

Benjamin Netanyahu was Israel’s finance minister in 2003. He went to London during the first half of the year looking for private investors for the project.6

Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline

One competitive challenge to a new and expanded pipeline to Haifa was the pipeline to Baniyas, constructed in 1952. IPC built this pipeline to replace the Haifa pipeline and to increase export volumes to the Mediterranean. The Baniyas pipeline was damaged in 1991 during the first Gulf War and had only started exporting again in 2000. Its capacity was about 300,000 b/d, but it only operated at half that amount during 2002.

This pipeline through Syria received a lot of attention from Makovsky. He insisted that it be destroyed during hostilities to punish Syria for helping Saddam bypass the UN’s oil-for-food program. Iraq had two authorized export channels under the oil-for-food program: the Iraq-Turkey pipeline (from Kirkuk, Iraq, to Ceyhan, Turkey) and the Al Basra Oil Terminal (ABOT) near Basra, Iraq.

At the time of our prewar planning, we were not aware that Makovsky had strong ties to Israel and the Mossad. I would learn years later that he had originally left the US in 1989 to join Israel’s foreign service. My US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) contact advised me that Israel’s foreign service consists about 98% of Mossad agents. The American Israeli Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), an Israel lobby organization in Washington, had originally placed him at the Pentagon during the summer of 2002.

Makovsky had no recognizable experience in the oil industry and no applicable experience in government, so his role on our team was somewhat contentious. The security people at the Pentagon refused to grant him a top-secret clearance and he refused to deploy to Iraq with the rest of us, remaining at the Pentagon as its so-called expert on the Iraq oil sector. Years later, I learned that Doug Feith over-ruled the Pentagon security group to get Makovsky his top-secret clearance.

Makovsky’s argument for destroying the pipeline made no sense to me. It was owned by Iraq and it was an export channel for Iraq’s crude. Syria’s only benefits were the toll fees and some minor synergy with their domestic oil production. Iraq would incur more than 95% of the punishment if we destroyed the pipeline.

The rest of our planning team agreed with me and President Bush’s cabinet adopted a policy in late 2002 of not destroying the pipeline. Instead, they decided to use it as leverage to get Syria’s cooperation. This was outlined in a January 2003 letter to Secretary Rumsfeld that was declassified in 2015.

The neoconservatives, however, dominated the Bush administration. Wolfowitz called for a video teleconference with General Tommy Franks about a week before the invasion. Franks was the Army four-star general commanding Central Command (CENTCOM) in 2003. Wolfowitz reversed the decision of the President’s cabinet and ordered the destruction of the pipeline.

In early April 2003 the pipeline’s pump station in Anbar Province was destroyed. It was the only intentional destruction of oil infrastructure during the war by the US military. Secretary Rumsfeld announced the day after the pipeline’s destruction that it was done to punish Syria for helping Saddam smuggle oil outside the UN’s oil-for-food program. This explanation was nonsense.

With the Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline destroyed, the path appeared to be clear for Chalabi to reopen the pipeline to Haifa and eventually expand it. During the summer of 2003 Chalabi consolidated his political power in Iraq under the Pentagon-controlled Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA). Ambassador L. P. Bremer, head of the CPA, appointed him as the president of the Interim Iraqi Governing Council in September.

The appointment of Dr. Ibrahim Bahr al-Ulloum as oil minister that same month was part of Chalabi’s plan. Ulloum told me that his appointment as oil minister was pre-determined. Ulloum was Chalabi’s guy.

Even while Chalabi and Ulloum were ascending, however, two problems emerged. The first could be fixed, but the second would prove insurmountable for Chalabi and the neoconservatives. During July 2003 it was learned that the Haifa pipeline no longer existed in most parts of Anbar province. The pipe joints had either been removed or had completely corroded.

That problem, however, could be fixed. The pipeline could be rebuilt. The second problem was overwhelming. It was a political problem.

Iraqi Oil Ministry employees, having read in the Baghdad Arabic newspapers that Americans intended to take Iraqi oil and ship it to Israel via a rehabilitated link to Haifa, attacked their own pipelines. The attacks forced closure of the Doura refinery, Baghdad’s primary source of gasoline and diesel.

Fuel shortages quickly dominated Iraq, gas lines stretching several miles throughout the country. Pictures of these lines also appeared on the front pages of American newspapers. The subsequent weekly video conference between the CPA and the National Security Council (NSC) became animated as one NSC leader lashed out, the gas lines making CPA and the Bush Administration look like they were losing control in the country.

Chalabi’s alternative plan

It would take me several years to understand the facts of what was happening. We suspected at the time that the attacks had to be an inside job. The attackers had to have access to pipeline maps to locate the pipelines that would inflict the biggest short-term damage to the stability of the country. Pipeline maps were very confidential in Iraq. Only members of the oil ministry had access to them.

The CPA oil team did not understand Iraqi politics and why insiders would be attacking their own pipelines. But the fact that it was happening did not escape Chalabi and his neoconservative partners back in Washington. The Haifa pipeline plan was just not politically feasible. Iraqis would not accept the shipment of their oil to Israel, an enemy since 1948. An alternative plan had to be executed to get Iraqi oil to Israel.

I received an unclassified enquiry from the intelligence community on Aug. 27, 2003. The analyst sourced the question as coming from Paul Wolfowitz: “Was Iraqi oil currently sold to Israel?” I responded that we knew who was buying the oil, but not its destination. Israel was not a buyer.

Follow up questions asked if the Iraqis were capable of tracking oil tankers after their departure from Iraqi ports to determine the destination port. There was only one way for tracking cargoes in 2003 and that was a subscription to Lloyds. Lloyds tracked all ships and their ports of call. But, I pointed out, the Iraqis did not subscribe to Lloyds.

A month after the Wolfowitz enquiry, Chalabi ordered the oil ministry to start selling crude cargoes to Glencore. Chalabi’s order violated the CPA policy of only selling Iraqi crude to end users (customers with refineries), but that would not stop him.

Phil Carroll (retired Shell US chief executive officer who became my boss in Baghdad in May 2003) was the director of the CPA oil group. Phil and I established the CPA oil sales policy in June 2003, focused on minimizing the risk of corruption while CPA was in control.

It was well known to many of us that oil traders had used nefarious practices to corrupt Iraq’s sales system during Saddam’s rule and earlier. The director of Iraq’s State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO) agreed with us. He was a strong supporter of the CPA policy and only sold oil to end-users. He refused to follow Chalabi’s order to sell oil to a trader. Chalabi removed the director and another Iraqi was appointed to sell to Glencore.

The timing of this activity was opportune. It occurred in early October 2003 just after Phil Carroll ended his CPA tour and I was in the US on a break. I voiced my objections upon returning to Iraq, but Ambassador Bremer had other priorities.

SOMO sold oil to Glencore for the rest of the CPA era. Chalabi could not meet his commitment of reopening the old pipeline to Haifa, but he was able to provide an acceptable alternative, moving the oil to Israel by tanker instead.

Current Israeli imports

Israel now receives much of its oil from the Kurdish government in northern Iraq. The Kurds started exporting crude more than 4 years ago after ISIS shut down Iraq’s export pipeline to Turkey. The Kurds built a pipeline through the Kurdish area of northern Iraq to intersect with the Iraq-Turkey pipeline where it crosses the Turkish border. This has been the only outlet for Iraqi crude produced in Kirkuk and the Kurdish areas since the ISIS attacks of 2014 and is the only current pipeline export channel for oil produced in northern Iraq.

Israel offers the Kurds a sanctuary for their oil. Many vessels departing Ceyhan with Kurdish oil visit the Israeli ports of Haifa or Ashkelon. The Iraqi government still treats any oil sold by the Kurdish government as smuggled. The Kurds cannot sell their oil to any country recognized by the Iraqi government, including the US. The Kurds have tried to ship cargoes to the US Gulf Coast in the past, only to be threatened with a seizure order through US courts. One ship (United Kalavyrta) was able to escape US customs in 2014 and eventually delivered its cargo to Ashkelon.

The Iraqi government does not recognize the government of Israel and so the Israeli courts remain out of reach for executing seizure actions on Kurdish oil. This arrangement has helped both provide oil imports to Israel and enable Israel to load a reversed EAPC pipeline between the Mediterranean port of Ashkelon and the Red Sea port of Eilat.

Some Kurdish oil exports also avoid Iraqi scrutiny by trans-shipping their cargoes at sea. The vessels’ transponders are shut off as they meet in the Mediterranean and pump the oil between them.

An oil agenda

If you had asked me 4 years ago if there had been an oil agenda behind the Iraq war, I would have said no, absolutely not. And I said no on national television in 2014.7

Ambassador Bremer and I went on the Rachel Maddow Show to refute Maddow’s position that the Iraq war was largely about oil. Specifically, I said that I had not witnessed any serious oil agenda during my 5 months of prewar oil planning at the Pentagon and 75 months in Iraq.

I cannot honestly say that today.

Phil Carroll and I agreed that if either of us saw anything close to an oil agenda in the summer of 2003, we would both resign and leave Iraq. Phil and I had spent time in the US Army before our careers in the oil industry and both of us detested the thought of US soldiers dying so that some oil company could profit.

We were looking for an agenda involving US oil companies. The President’s critics were looking for the same thing and even inferred in the US press that an oil-driven agenda was being executed. We did not see any such agenda.

Up until 2013 my focus remained on executing plans to help the Iraq oil sector as best I could. I had little desire to research an oil agenda.

There were several facts I discovered while researching my book, however, that made me realize that I had been in denial about an oil agenda for the Iraq war.

First, Israeli infrastructure minister Joseph Pritskzy was interviewed in the Israeli press on March 31, 2003, before US Forces had even taken Baghdad, identifying how the Iraq war would benefit Israel economically. He was in contact with civilians at the Pentagon planning to reopen the pipeline between Kirkuk and Haifa. Pritskzy said that Israel was paying a 25% premium on its oil imports and that the reopened pipeline to Haifa would eliminate this premium.

Second, Israeli finance minister in 2003 (and current prime minister), Benjamin Netanyahu, went to London in 2003 to find investors willing to expand the Kirkuk-to-Haifa pipeline.

Third, the number-three person at the Pentagon in 2003 was Doug Feith. Feith’s law partner for 15 years before joining the Bush administration was Marc Zell. Zell is quoted as saying that Chalabi promised to reopen the Kirkuk-to-Haifa pipeline and enable a huge amount of business between Iraq and Israel.8 Zell further criticized Ahmed Chalabi as “a treacherous, spineless turncoat.”

Fourth, Scooter Libby was Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff. Libby had a secure communications link to Chalabi in Baghdad during the summer of 2003. Libby was also linked to oil trader Marc Rich. As mentioned earlier, Rich was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office for crimes of income tax evasion of $100 million and trading with the enemy.

Libby was Marc Rich’s lawyer for many years while Rich made billions of dollars moving Iranian crude via a secret pipeline through Israel. He moved the oil through Israel to his customers in the Mediterranean and Israel received the oil it needed at a discounted price. This arrangement stopped sometime after 1994 when Rich was forced out of the company he founded.

Both Marc Rich and Scooter Libby developed a very close relationship to the Israeli government and especially Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency. The former British foreign secretary from 2001 to 2006 was Jack Straw. Straw said of Scooter Libby, “It is a toss up whether he is working for the Israelis or the Americans on any given day.”9

The last factor was Mike Makovsky’s role as part of EIPG in October 2002. Why was a Mossad contact with no oil experience placed in a key Iraq oil position at the Pentagon from 2002 through 2008? To support supplying Iraqi oil to Israel. He remains in Washington as CEO of the Jewish Institute for National Security of America.

Many of us volunteers in 2003 thought weapons of mass destructions were our reason for war with Iraq. But history should accurately reflect an agenda of providing Iraqi oil to Israel regarding the Iraq war. The costs of that war were huge: over 4,500 dead Americans (military and civilian), 33,000 seriously injured and over $2 trillion spent by the US Treasury. The country of Iraq incurred huge costs as well. The number of Iraqis killed or injured dwarfs our statistics.

References

1. Times of Israel, “Former Israel-Iran oil company to continue operating in secret,” Dec. 31, 2017.

2. Ammann, D., “The King of Oil: The Secret Lives of Marc Rich,” St. Martin’s Griffin, 2009, New York, NY.

3. The Guardian, “Israel Seeks Pipeline for Iraqi Oil,” Apr. 20, 2003.

4. The Guardian, “Curveball: How US was duped by Iraqi fantasist looking to topple Saddam,” Feb. 15, 2011.

5. Vogler, G., “Iraq and the Politics of Oil: An Insider’s Perspective,” University Press of Kansas, 2017, Lawrence, Kan.

6. Reuters, “Netanyahu Says Iraq-Israel Oil Line Not Pipe-dream,” June 20, 2003.

7. NBC News.com, “The Rachel Maddow Show,” Mar. 6, 2014.

8. Dizzard, J., “How Ahmed Chalabi conned the neocons,” Salon, May 4, 2004.

9. Kampfner, J., “Blair’s Wars,” Free Press, 2003, New York, NY.

The author

Gary Vogler ([email protected]) is president of Howitzer Consulting LLC. He authored “Iraq and the Politics of Oil: An Insider’s Perspective,” published by the University Press of Kansas in November 2017. From December 2006 to September 2011 he was a senior oil consultant for US Forces in Iraq, and before that he served as deputy senior oil advisor, Coalition Provisional Authority, for Baghdad, and as senior oil advisor, Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, for the Pentagon, Kuwait, and Baghdad. Vogler is a former US Army officer and West Point graduate. He also worked in management positions at ExxonMobil and Mobil Oil Corp. for more than 20 years.