Rig Health-Risk Audits Will Benefit Operators, Contractors

Like other heavy industries, drilling for oil and gas can pose a significant risk to health. However, unlike most heavy industries which are static in terms of location and workforce, the fact that drilling operations are often undertaken in hostile and remote environments and are worked by personnel who lead nomadic lifestyles means the potential for exposure to health hazards is increased.

Research suggests that offshore drilling personnel are five times more likely to be injured than other offshore workers. Industry figures report average annual total lost time accidents at 1,294 and, more poignantly, an average annual total fatality rate of 23 (1996 through 1998).1 2

Given this potential for harm, it should be the aim of operators who commission work, and drilling companies who undertake it, to ensure that hazards to health are suitably identified and that effective controls or arrangements are put in place to prevent or limit exposure.

There is assessment methodology that can achieve this aim and enable both parties to discharge their legal duties and demonstrate their commitment to improving health performance.

Hazard, risk profile

Many of the health hazards associated with drilling operations are well known and can be placed into two categories: inherent and environmental.

Inherent health hazards arise from rig activities such as:

- Moving pipe around the rig.

- Working with rotating equipment on the drill floor.

- Working at height on the derrick.

- Using electrical equipment.

- Chemical handling in the sack room.

- Hot work during welding and cutting.

Environmental health hazards can result from exposure to:

- Extremes of climate, heat and cold.

- Animal vectors.

- Unsafe water supplies contaminated at source or in transit.

- Poor food hygiene causing food-borne illness.

- Unsanitary living accommodations.

- Poor local infrastructure affecting roads, communication, and health care.

The risk of such potential hazards actually resulting in harm is often influenced by human factors such as:

- Macho attitude to safety.

- Poor training.

- Language difficulties affecting communication.

- Inadequate appreciation of the dynamics of health care.

- Delegation of responsibility for personal safety to a higher being.

The severity and frequency of exposure to risk are graphically illustrated by industry safety alerts (published this year) that report the following cases:

- Drill pipe slip. In this incident, an employee's hand was caught between the slips and the elevators resulting in the traumatic amputation of a finger. The subsequent incident investigation concluded that crew composition and lack of experience were contributory factors.3

- Third-party electrocution. In this incident, subcontractor equipment did not match the rig's electrical equipment. Consequently, the equipment was unsafe and as a result of accidental contact, an employee was fatally electrocuted.4

- Forklift accident. In this incident, a forklift was being used during the rigging up of the derrick board. Excessive force separated a support chain causing two employees to fall from a height. One employee struck his head on a rock and sustained multiple fractures to the skull resulting in death.5

- Fatal crane accident. In this incident, a bundle of tubing was being lifted from a vessel by crane and the load was inadvertently lowered onto a roustabout. The employee was crushed beneath the load and died from his injuries.6

Given these examples and accepting that many rigs will have similar hazard and risk profiles due to the nature of the business, it is essential that each rig have appropriate health care provision available to deal with system and/or people failures.

Methodology

The following methodology has been developed to address these issues and comprises four key elements:

Health contract clauses

Health contract clauses included in the invitation-to-tender document provide a means of obtaining information from the prospective drilling company regarding its plans for minimizing health risk, and health care provision.

The clauses reflect legislative requirements and best industry practice and suggest the standard of controls and arrangements to be delivered.7-13

In responding to the contract clauses, the drilling contractor is required to provide details of the following:

- Company health policy.

- Company medical adviser.

- Standard of medical assessment for company and subcontractor personnel (e.g., food handlers, crane drivers, rescue team members).

- Arrangements for medical support for the duration of the contract.

- Medical repatriation plan.

- Immunization programs.

- Rig medics.

- Rig caterers.

- Inventories.

- Emergency procedures.

- Previous assessments (e.g., noise).

- Previous audits (e.g., food safety).

Evaluation

Evaluating the information provided by the tender response requires both objective and subjective judgments to be made on the part of the assessor. The amount and quality of information provided can be simply scored by calculating the percentage response rate.

This score can then be considered along with other factors such as prior operational performance, the duration and location of the well, and existing knowledge of local conditions and infrastructure.

When combined, these data produce a "total score" which helps to determine the quotient of health risk for a particular rig and indicates the need for further practical assessment by technical audit.

Technical audit

Technical audit is concerned with the systematic assessment of measures taken to minimize health risk. In practice, the process utilizes structured interviews with key personnel and physical inspection to confirm and evaluate the quality of provision.

While measures tend to vary from rig to rig, depending on the location of the well (whether at sea, in swamp or on land), the following "constants" of provision should be present to limit risks to health:

- Location medical support.

- Rig medics.

- Rig medical facilities.

- Rig emergency plans.

- Catering practice.

- Potable water supplies.

Location support

Location medical support generally consists of 24-hr telephone advice, the facility to provide on-site medical assistance, and prompt access to specialist health care professionals.

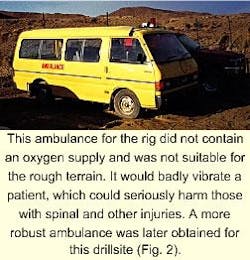

Assessing the quality of such provisions is achieved by considering the contract placed with local providers and hospitals, reviewing contact lists and call-out times, and inspecting facilities, emergency response kits, and transportation arrangements.

Medics

Rig medics usually have nursing, military, or medical backgrounds and varying degrees of training and skills. Under UK law, a medic is deemed competent if he or she undergoes periodic training (every 3 years) and is certified by an approved training center.

For those medics who do not possess such certification, their competence is assessed by a review of their qualifications and experience against current knowledge of subjects included in the certification syllabus such as: casualty handling, advanced resuscitation, burns management, and food safety.

In addition, their ability to operate equipment, their standing with the crew, and language competence are other key factors taken into consideration during the assessment.

Medical facilities

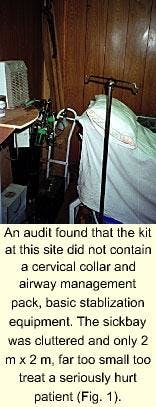

Rig medical facilities vary in structure and can affect the delivery of care if poorly designed. To be acceptable, the facility should be constructed of material that can be easily cleaned and have sufficient space, storage, and lighting to enable effective patient management.

It should have suitable means of access and egress, and the route to the helideck, in the case of a marine rig. It should not increase the potential for harm. The facility should be equipped with suitable levels of medications and equipment.

An acceptable inventory is one in which the range of products held is determined by a medical adviser or pharmacist and, as a minimum, which complies with industry best practice. Additionally, all stocks should be checked to ensure that they are within their expiration dates and temperature controlled as required.

Controlled drugs should be securely stored and checked by the rig medic and the rig manager at least once a tour. Levels of equipment should match the training competence of the rig medic and enable investigation and stabilization. The age and condition of equipment is also considered along with evidence of planned equipment maintenance.

Emergency plan

Rig emergency plans for managing multicasualty incidents and medical repatriation can be assessed against best practice. An effective triage plan should consist of a means of identifying and prioritizing casualties, preprepared patient packs, first-aid support, suitable accommodations, and effective communications.

In addition, there should be evidence of triage drills and first-aid refresher training.

An acceptable medical repatriation plan identifies the receiving hospital, provides names of contacts, communication information, and details of routes and transit times. The plan should also make provision for an escort, both from the rig and during onward transportation.

Catering

Catering practice is assessed against standards contained in the catering company's operations manual or, if such a system is unavailable, industry standards. The camp boss and catering crew are key to ensuring hygienic conditions, and their training competence and health screening prior to employment is assessed in the first instance.

A safe food supply is also a major consideration; this is reviewed with regard to how food supplies are obtained and transported to the rig. Galley facilities have a significant effect on practice and should be designed and constructed to ensure the safety of food production.

Ideally, they should be large enough to allow segregation of food processing and have adequate extraction and levels of lighting. Fittings and fixtures should be of stainless steel and moveable to aid cleansing.

Floors should be suitably tiled and have sufficient drainage points to facilitate sluicing. Food storage should be well organized and freezers and refrigerators should be maintained at the correct temperatures (-18° C. and 8° C., respectively).

A stock-rotation system should be employed, and any unlabelled produce received should be week and year date marked.

Galley equipment, such as knives and slicing machines, are a ready source for cross contamination, and evidence of regular cleaning, in the form of cleaning schedules, would be reviewed.

Finally, arrangements for dealing with galley waste are reviewed to ensure that disposal does not have adverse environmental consequences.

Water

Potable water supply to a rig is usually bunkered from a supply vessel or tanker, made on the rig, or provided as bottled water. Procedures to ensure regular hose, filter, and tank cleaning and emergency treatment would be expected and their implementation confirmed by visual inspection.

The effectiveness of arrangements for ensuring control of pathogenic bacteria, by chlorinating the supply to ensure a chlorine content of 0.2-0.5 ppm at outlets, can be tested by reviewing the results of periodic bacteriological and chemical analysis.

After assessment of the constants, specific measures made as a consequence of rig risk assessments can be reviewed. These may range from habitats to provide solar protection to protective personnel equipment supplied to prevent exposure to hazardous chemicals.

The adequacy of such measures can be simply assessed by temperature monitoring and reviewing protection factor information along with wearer compliance.

On conclusion of the technical audit, findings should be discussed with rig management so that minor issues can be addressed promptly.

The resultant technical audit report summarizes major findings, contains pragmatic recommendations for improvement, and provides guidance for their implementation.

Such recommendations can be prioritized and given time scales, depending on the degree of provision failure and the consequent increased potential for harm.

Common provision failures are revealed by a simple study of the results of 26 technical audits. The results are shown in an accompanying box.

Health-performance indicator

While key performance indicators are extensively used in facilities management, they are a relatively new concept to the exploration and production industry in terms of monitoring health performance.

Health-performance indicators are said to be useful in:

- Helping to protect the health of employees and others.

- Demonstrating line management's commitment to continuous health improvement.

- Giving line management a better understanding of health issues relevant to its operational responsibility.

- Enabling measurement of performance against predetermined targets.

- Highlighting important health issues and setting priorities.

- Maintaining credibility and confidence both within the company and towards the general public and stakeholders.

- Benchmarking.

- Improving cost effectiveness.14

Indicators can be both proactive (e.g., the number of health risk assessments undertaken in a given period) and reactive (e.g., reporting the incidence of occupationally related illness, per million man-hours).

In terms of the methodology described, the latter was adopted for rigs taken on hire to gauge the effectiveness of their controls. Its introduction required development of a guidance document and a hardcopy reporting system.

The benefits of employing such a methodology for assessing drilling-rig health risks are best illustrated by considering case studies and case law.

Management awareness

An audit of a rig taken on hire to drill a well in UK waters discovered that, although the rig medic had a good knowledge of resuscitation algorithms, he did not have access to an automatic external defibrillator (AED).

As a consequence, one of the recommendations in the audit report was for the drilling company to undertake a cost-benefit analysis to establish whether it would be reasonable to purchase such equipment.

This caused a degree of consternation within the drilling company, as it had wider fleet implications and resulted in the line manager responsible for the project questioning the validity of the recommendation.

Consequently, the moral argument that "rig personnel had the same right to defibrillation, in the event of a heart attack, as other members of the population" was used to substantiate the recommendation in the first instance.

This view was further supported by discussion of legal responsibility and the concept of "practicable vs. reasonably practicable" (standards of UK health and safety law which take into account the feasibility and cost of protective measures).

The outcome of the deliberation was that the line manager negotiated the placement of a redundant AED on the rig for the duration of the well and its return at the end of the contract.

This initiative, however, did prompt the drilling company to reconsider its decision, and most of its rigs are now equipped with AEDs. (A wise decision in the light of a recent case in which a German airline paid $3 million in damages for not having AEDs on its aircraft.15)

Improved facilities

Again, an audit of a rig taken on hire in UK waters found that the rig medical facility had bunk beds attached to three bulk heads, which greatly reduced the space available for patient management.

Therefore, if confronted with a casualty, the rig medic was compelled to treat the patient on the bottom bunk and accept the risk of head or back injury or both. This problem was highlighted in the technical audit report, and it was suggested that such arrangements breached UK regulation.

The drilling company explained that as a marine vessel, the rig was required to have a certain number of bunks for registration purposes. After further consideration, however, and to the company's credit, the facility was remodeled so that effective patient care could be delivered.

A second case relates to an audit of a drillship that had been stacked in the Arctic for a number of years and was being recommissioned to work in the Far East.

On this occasion, it became apparent that the antiquated ventilation system was not going to be able to provide sufficient cooling, given the ambient temperature and humidity levels experienced in the region, and that poor thermal comfort would adversely affect the crew.

Taking the recommendation for air conditioning to be installed into consideration, the drilling company at its own expense invested heavily in air conditioning units and improved ducting so that thermal comfort could be achieved in all areas of the accommodation module.

Knowledge sharing

By definition, rig medics work alone and have little opportunity for contact with fellow professionals, especially when unsupervised by a medical adviser. Such isolation must inevitably affect levels of confidence, competence and, over time, performance.

The technical audit therefore provides an opportunity for the rig medic to meet colleagues, discuss weakness in provision, and benefit from knowledge sharing.

Most notably, a doctor working on a rig in Pakistan identified that immediate-care training in his country was not readily available and requested appropriate information. Consequently, information and papers were dispatched on return to the UK, and these were eventually used to develop rig protocols, before being shared with colleagues.

Additionally, the technical audit also presents an opportunity to share knowledge with rig management, particularly in respect to accepted occupational exposure standards.

Legal compliance

Companies operating in the UK must comply with health and safety legislation which requires an employer to "assess the risks to health and safety of those in his employment and those connected with his undertakings."16 17

While this requirement seems unequivocal, in making the employer (operator) responsible for assessment, the question of "Who is liable?" is often raised.

The legal answer appears to be provided by the cases of Regina vs. Associated Octel Co. Ltd. and the Health & Safety Executive vs. Port Ramsgate Ltd.

As a result of these cases, the courts found respectively that an employer has a duty to exercise control of an independent contractor employed by it and that he is also responsible for undertaking detailed risk assessments, especially at the procurement stage.18

On the basis of these rulings, it seems safe to say that the methodology described here offers a pragmatic solution to assessing the drilling rig for health risks. In the author's case, it also fulfils an objective of the company's health, safety, and environmental policy in that, wherever in the world the company operates, it is committed to achieving a high level of HSE performance.19

References

- Nelson, Norman J., and Brebner, J.A., The Offshore Health Handbook. London;Dunitz, 1987: 15.

- International Association of Drilling Contractors, Accident Statistics Program. http://iadc.org/asp/aspstats.htm.1999.

- International Association of Drilling Contractors Alert 99-11, http://iadc.org/alerts/ sa99-11.htm

- International Association of Drilling Contractors. Alert 99-21, http://www.iadc.org/alerts/sa99-21.htm

- International Association of Drilling Contractors. Alert 99-02, http://www.iadc.org/alerts/sa99-02.htm

- International Association of Drilling Contractors. Alert 98-32, http://iadc.org/alerts/sa98-32.htm

- First aid on offshore installations and pipeline works. Offshore Installations and Pipeline Works (First-Aid) Regulations 1989 and Guidance, London: MSO, 1990.

- E&P Forum, Guidelines for the Development and Application of Health, Safety and Environmental Management Systems, Report No. 6, 36/210, 1994.

- E&P Forum, Health Management Guidelines for Remote Land -Based Geophysical Operations, Report No. 6.30/190, 1993.

- E&P Forum, Standards for Local Medical Support, Report No. 6.44/222, 1995.

- United Kingdom Offshore Operators Association, Guidelines for Medical Aspects of Fitness for Offshore Work, Issue No. 3, 1995.

- United Kingdom Offshore Operators Association, Guidelines for Environmental Health for Offshore Installations, Issue No. 3. 1996.

- United Kingdom Offshore Operators Association, Guidelines for the Management of Competence and Training in Emergency Response, Issue No. 1. 1997.

- E & P Forum, Health Performance Indicators, Report No. 6, 78/290, 1999.

- Hall, M., Call for heart machines in aircraft, The Daily Telegraph, Aug. 1, 1998.

- Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulation 1992 and Approved Code of Practice, London, HMSO, 1992.

- Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, London, HMSO 1974.

- Washbourne, P., and Dees, D., Health and Safety Implications of the Ramsgate Decision,Construction Law, 1998, Vol. 9, Part 10, pp. 327-30.

- BG plc Corporate Affairs, Health, Safety and Environmental Policy, 1997.

The Author

Until a new assignment recently, Bob Hanson was senior occupational health advisor for BG plc at Reading, UK. He qualified as a registered general nurse in 1976 and a mental health nurse in 1979. He joined Britoil in November 1979. In 1986, Hanson moved from the North Sea when he became a nursing officer with CABGOC (a subsidiary of Chevron) in Angola.

In 1991, Hanson returned to work in the UK and joined the occupational health department of British Gas (now BG plc). He has a diploma in food hygiene and a post-graduate diploma in occupational health. He has recently been reassigned to the loss-prevention function within BG International.

Failures revealed by audits

- 50% of rig medics did not have a medical adviser supervising their work.

- 12% of the rig medics interviewed were considered to have inadequate training competence.

- 38% of inventories were designed by the rig medics.

- 35% of sick bays were considered to be inadequately equipped.

- 81% of rigs did not have a triage plan or arrangements.

- 69% of rigs did not have adequate first-aid support.

- 8% of rigs did not have adequate oxygen supplies.

- 46% of rigs were considered to lack acceptable standards of food safety.

- 50% of freezers could not maintain recommended temperatures.

- 58% of food handlers had not received appropriate training.