Arizona-New Mexico CO2-helium deposit detailed

The St. Johns-Springerville area of eastern Arizona and western New Mexico could prove to be a substantial discovery of naturally occurring carbon dioxide. That conclusion is possible if 13 wells still being tested justify construction of a pipeline to deliver the CO2 to enhanced oil recovery markets in California or southeastern New Mexico and West Texas.

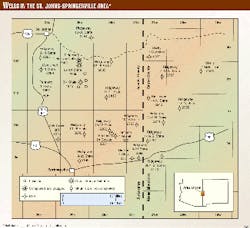

The St. Johns-Springerville area consists of about 700 sq miles in Apache County, Ariz., and Catron County, N.M. (Fig. 1).

Ridgeway Arizona Oil Corp. reported in December 1998 that it had leased about 400,000 acres in the area in connection with its carbon dioxide project. Acreage is mostly state and private land in Arizona and federal land in New Mexico.

Two major coal-fired electric power plants are in the area. The Tucson Electric Power plant southeast of St. Johns has been included in several proposed options for the processing and development of CO2.

St. Johns stratigraphy

Permian, Triassic, Cretaceous, Tertiary, and Quaternary rocks are exposed in the St. Johns area.

Surface rocks are mainly Triassic redbeds near St. Johns and Tertiary to Quaternary volcanic rocks near Spring- erville. The volcanic rocks near Spring- erville are part of the widespread White Mountain-Springerville volcanic field. Precambrian granite underlies the Permian rocks at depths between 2,200-3,200 ft.

Permian strata include San Andres limestone, Glorieta sandstone, and the Supai formation. The terminology used by Winters1 to define the widely exposed Supai formation in the Fort Apache region is readily applied to subsurface wireline log correlation of the Supai formation in the St. Johns-Springerville area. From the top, it consists of the Corduroy, Fort Apache, Big A Butte, and Amos Wash members. This rock grouping contains the Yeso and Abo formation equivalents in adjoining New Mexico.

The Corduroy member of the Supai formation consists of very fine-grained, redbed clastics interbedded with thin anhydrite and carbonate beds. Depth to the top of the Corduroy member varies from 640-1,632 ft. The Corduroy member is 596-756 ft thick in the mapped area.

The Fort Apache limestone member of the Supai formation is a distinctive marker unit that can be regionally traced throughout central and east-central Arizona. In the subsurface, the base of the Fort Apache member is easily picked in well logs because it is characterized by a distinctive gamma ray log curve break (Fig. 2). It is an important subsurface correlation horizon in central and east-central Arizona and western Catron County, N.M. (Fig. 3).

The Fort Apache limestone member generally consists of an upper anhydrite with anhydrite-laminated very fine grained sandstone and lower vuggy dolomite in the St. Johns-Springerville area. Depth to the top of the Fort Apache member ranges from 1,290-2,208 ft. The Fort Apache member is 64-108 ft thick. Available conventional core plug porosities range from 3.1-26.7% in the siltstone and 3.5-30.1% in the dolomite. Core plug permeabilities vary from 0.01-0.78 md in the siltstone and 0.01-232.77 md in the dolomite.

The Big A Butte member of the Supai formation consists of thin anhydrite and dolomite beds within a section of very fine grained redbed clastics. A thin argillaceous limestone defines the base of the Big A Butte member in the Fort Apache region. The lowest anhydrite or carbonate also marks the base of the Big A Butte member in the St. Johns-Springerville area. Depth to the top of the Big A Butte member varies from 1,368-2,370 ft. The Big A Butte member is 266-416 ft thick. Conventional core plug porosities range from 2.7-30.3% in the very fine grained clastics and 0.4-21.5% in the dolomite. Core plug permeabilities vary from <0.01 to 312.44 md with one plug reading as high as 1,618.65 md in the very fine grained sandstone and <0.01 to 19.2 md in the dolomite.

The Amos Wash member of the Supai formation consists of red to maroon mudstones, siltstones, and very fine grained sandstones. Patches or channel fills of conglomerate and granite wash are present at its basal unconformable contact with Precambrian granite. Purple-green, highly fractured, deeply weathered and altered igneous rock underlies the Amos Wash member in one well. Ridgeway has reported gas in the granite wash at the base of the Amos Wash member.

Depth to the top of the Amos Wash member ranges from 1,652-2,636 ft. The Amos Wash member is 404-760 ft thick. Full diameter conventional core porosities of the basal conglomerate and granite wash of the Amos Wash member range from 4.1-8.1%. Full diameter core permeabilities vary from 0.17-1.44 md with one reading as high as 18.92 md.

Structure in the area

Permian strata in the St. Johns-Springerville area form a broad, asymmetrical anticline trending northwest (Fig. 3). The axis plunges to the northwest and southeast. Dips are steeper on the faulted, southwest flank. Faulting extends into Precambrian granite and is probably controlled by Precambrian structure.

A small northwest-trending fault and several smaller anticlines are superimposed on the broad anticlinal fold. A steep monoclinal dip observed at the surface splits the northwest plunge of the broad fold and may represent a northern segment of the northwest-trending fault.

The broad anticline in the St. Johns-Springerville area gives way to the south to a broad syncline or basin in the White Mountain volcanic area. The broad syncline was revealed in 1993 when the Tonto 1 Alpine Federal well, north of the town of Alpine, was continuously cored to 4,505 ft.2 The broad syncline may represent a concealed salt basin.3

Carbon dioxide in wells

The first recorded report of naturally occurring CO2 in the St. Johns-Springerville area was from the Mae Belcher 1 State well drilled about 12 miles east of Springerville in 1959. A flow of CO2 was reported from the Belcher well that was estimated at 2.5 MMcfd and contained a reported 78-87% CO2 with 0.17% helium.

Ridgeway in 1994 drilled the Ridgeway/Canstar 1 Plateau Cattle well as an oil test about 7 miles southeast of St. Johns. The company announced the well as a CO2 discovery. Initial production was reported at 640 Mcfd of gas and 436 b/d of water from the Fort Apache and Big A Butte members of the Supai formation. Ridgeway stop- ped the water production by squeezing cement into the Fort Apache perforations.

Gas analysis by the U.S. Bureau of Mines in Amarillo, Tex., indicated 90% CO2, 6% nitrogen, and 0.5-0.8% helium. Ridgeway has reported higher percentages of CO2 in other wells.

The 1 Plateau Cattle well was replaced by an offset well, the 22-1X State, in 1997 because the CO2 and initial water production corroded the steel pipe used in its completion. As a result, Ridgeway used fiberglass casing for the long string in its 1997 drilling series in Arizona to avoid corroded steel casing as experienced in the 1 Plateau Cattle well.

Ridgeway in 1995 drilled a follow-up well, the 3-1 State, 4 miles south of the 1 Plateau Cattle well. Ridgeway completed the 3-1 State for a reported 657 Mcfd from the Big A Butte member of the Supai formation. USBM analysis indicated 89% CO2, 10% nitrogen, 0.7% helium, and 0.1% each of methane and argon.

Based in part on the presence of CO2 in the Mae Belcher well east of Springerville and the 1 Plateau Cattle and 3-1 State wells southeast of St. Johns, Ridgeway drilled a series of 11 widely-spaced wells between St. Johns and Springerville in early 1997. Ridgeway continued the series with six wells in western Catron County, N.M., in late 1997 and early 1998.

Of the 11 wells Ridgeway drilled in Arizona in 1997, two were plugged as dry holes, one was completed as a replacement well for the corroded 1 Plateau Cattle well, and eight are shut-in until testing is completed. Of the six wells Ridgeway drilled in New Mexico in late 1997 and early 1998, one was plugged as a dry hole and five are shut-in pending completion testing.

The replacement well, the 22-1X State, was completed in June 1997 for a reported 1.894 MMcfd of gas from the lower Big A Butte member of the Supai formation. Ridgeway has reported higher flow rates in other wells. Initial completion testing indicates potential water problems in some wells.

Ridgeway ran 10 drillstem tests in four of the wells it drilled in Arizona between 1994-97 and a reported five DSTs in four of the wells it drilled in New Mexico. Complete DST results are not yet available for some of the wells drilled in New Mexico.

Ridgeway cut 689 ft of conventional core in three of the wells it drilled in Arizona in 1997 and 766 ft of conventional core in five of the wells it drilled in New Mexico. The core is stored and is available for study at the Arizona Geological Survey in Tucson and the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources in Socorro.

In April 1998, after completing its drilling program, Ridgeway requested the U.S. Bureau of Land Management in New Mexico to initiate an environmental impact study of its CO2 project area.

Ridgeway subsequently proposed a large exploration unit extending into New Mexico. Snow Oil and Gas Inc. proposed two smaller exploration units bounded by the state line. The various proposed units range from about 110,000 to 265,000 acres.

Origin of CO2

Postulated origins for CO2 in the region include primarily decomposition of calcite at McElmo Dome field in southwestern Colorado to primarily migration from the upper mantle (juvenile source) at Bravo Dome field in northeastern New Mexico.

Proximity to extensive volcanic fields and basement-controlled faulting suggest a primarily juvenile source for the CO2 in the St. Johns-Springerville area. On the other hand, vast travertine deposits and extensive lost circulation in widespread fractured and cavernous Permian carbonate strata in the area suggest that some CO2 is the result of dissolution of carbonate rocks by groundwater.

References

- Winters, S.S., Supai formation (Permian) of eastern Arizona, Geological Society of America Memoir 89, 1963, 99 p.

- Rauzi, S.L., Geothermal test hints at oil potential in eastern Arizona volcanic field, OGJ, Jan. 3, 1994, p. 52.

- Rauzi, S.L., Concealed evaporite basin drilled in Arizona, OGJ, Oct. 21, 1996, p. 64.