Maturing planet, tougher terms change upstream landscape

These are dramatic times upstream-more competitive and demanding.

Geological potential is not as exciting, and contract/fiscal terms are tougher relative to the dwindling potential.

Furthermore, exploration acreage has taken on the characteristics of a commodity. This stems from stiff competition between companies for exploration opportunities. There are more companies than ever before seeking opportunities worldwide, and never have so many countries been open for business.

Each year, 40-50 countries conduct official license rounds or "block offers." Of these, nearly one third were not even "open" 10 years ago. In addition to official license rounds, many countries entertain offers and negotiations "out-of-round." Each year about 20 countries change their petroleum fiscal systems and more countries than that introduce new petroleum laws, model contracts, or regulations.

Also, countries are more proactive in their efforts to compete with each other. For example, in November 1996 Indonesia's national oil company, Pertamina, dispatched representatives to make promotional presentations to industry in Houston and London. It was the first time Pertamina had done this after more than 3 decades of heavy licensing activity. The focus was on the country's geological prospectivity and contract terms-a common formula.

In efforts to compete, many countries are fine-tuning their terms or at least agonizing about whether or not to do so. But the fine-tuning comes slowly and often does not match the waning prospectivity. One reason is that so many attempts by governments to soften terms are met with aggressive competitive offers from companies.

What is a country to do?

With so much competition for projects and acreage, governments are more aware of what the market can bear. Furthermore, governments are demanding faster acreage relinquishment to turn it over more quickly and get it back on the market.

Next-century exploration

Exploration is simply not what it was even a generation ago.

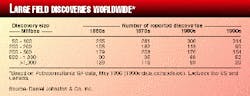

More than 80% of the world's oil production comes from fields discovered before 1973.1 Giant discoveries are not a thing of the past yet they are rare these days (see table 2). Furthermore, where giant field potential does exist, it is usually in deepwater frontiers or hostile regions in terms of climate and/or politics.

Two key elements in the exploration business are estimates of the probability of success (sometimes called chance factor) and the anticipated or target field size.

Postmortem analysis of exploration efforts the past couple of decades indicates we have been optimistic in our estimates of success probabilities as well as field size distributions.3 Success rates are not as high, and discoveries typically have not been as large as expected.

Companies have managed to replace reserves but only partially through exploration. There is intense pressure on companies to "book" barrels to measure up in terms of reserve replacement ratios and finding costs. But, pure exploration is not replacing production.

Contract terms

Even on the threshold of this new century, the science of fiscal system analysis and design is burdened by a lack of standardization of terminology.

And many concepts are not widely known or understood. This is particularly true of two fundamental concepts: the division of profits "take" and the division of revenues captured by the "effective royalty rate" statistic.

State take

While there are numerous means by which governments obtain a piece of the pie, the four main rent extraction mechanisms are:

- Signature bonuses.

- Royalties.

- Profits-based elements.

- National oil company (NOC) participation.

Contract analysis focuses on the division of profits or take. The chart comparing fiscal terms for oil shows how 55 typical or standard systems compare on the basis of the division of profits from the government point of view. The systems are ranked on the basis of state take.

Generally speaking, of course, countries with the tougher terms have more prospective acreage. However, there are anomalies on charts like this. The division of profits is important but it does not capture everything embodied in a given system.

Take definitions:

Cash flow, $ = cumulative gross revenues less cumulative gross costs over life of the project (full cycle).

State take, % = government receipts (from royalties taxes, bonuses, production or profit sharing, plus NOC share of profits through government working interest participation) divided by cash flow.

The state take statistic effectively collapses the various means by which governments obtain a share of profits (total cash flow) into an overall effective tax rate.

Take statistics are not a perfect measure but they provide valuable information. For example, signature bonuses do not get adequate representation in the typical take statistics.[ref. 3] Also, from the state take point of view, there is no difference between a 50% tax and 50% government risk-free carry where the NOC pays its way through development.

About 40% of the NOCs worldwide have the option to take up a working interest (i.e., back-in) once a discovery is made.

From an oil company financial point of view the "carry" is not as burdensome as a tax of the same rate. But from an "entitlement" point of view, there is a big difference, because companies would not be able to book as many barrels with a NOC back-in. So exploration decisions are influenced by government participation options (the carry), but field development economics are not.

Having the NOC as a partner is not much different from having another oil company as a partner from a development feasibility point of view. Similarly, with production acquisitions or sales it generally does not matter who the partners are.

A common concern about typical take statistics is that timing of cash flows is not considered. This is because the statistics normally reflect the nominal division of profits (cash flow) without factoring-in present value discounting.

State take from a present value point of view is always greater than nominal state take. For example, world average state take is about 67%. Discounted at 12.5%, the average can range from 80% for profitable situations to more than 100% for marginal to submarginal fields.

Take statistics also do not capture the importance of ring-fencing or the important exploration incentive that can be created by the lack of a ring-fence.

Despite various weaknesses, the division of profits has always been important. However, the concept is burdened by a confusing diversity of terminology.

Other somewhat similar terms that are used include:

- Tax take.

- Marginal government take.

- Government take.

- Government fiscal take.

- Government financial split.

- Government bottom-line income split.

- Net cash margin.

- Net net.

'Effective royalty rate'

The effective royalty rate (ERR) is the minimum share of revenues a government would expect in any given accounting period.

In a royalty/tax (R/T) system, the royalty will guarantee the government a share of revenues (or production). If there are sufficient eligible deductions, the company or contractor group may pay no tax in a given accounting period. The government would receive the royalty.

Production-sharing contracts (PSCs) typically differ from R/T systems because royalty payments and cost-recovery limits (unique to PSCs) guarantee the government a share of revenues (or production).

The ERR calculation is based on a single accounting period (not full cycle) and the assumption that costs and eligible expenditures or deductions exceed gross revenues. This tests the limits of the system. This situation often occurs in early stages of production or at the end of the life of a field when cost recovery is at its limit and deductions for tax calculation purposes exceed taxable income.

The chart provides examples of the diversity of ERRs worldwide.

Some countries such as the U.K. and Indonesia have no royalty, yet the Indonesian standard contract has a cost-recovery limit that guarantees the government at least 14% of production in any given accounting period. World average ERR is about 20%.

Egyptian PSCs have some of the highest ERRs in the world because of low cost-recovery limits with profit oil splits of 80/20%, or so, in favor of the government. In any given accounting period regardless of accumulated costs or deductions, 60% of the production is forced through the 80/20% profit oil split-this guarantees the government 48% of the production:

60% x 80% = 48%

While the take calculations deal with division of profits full-cycle, ERR calculations focus on division of revenues in a single accounting period (assuming unlimited costs). It provides insight into a common concern companies have about how quickly they can recoup costs.

If the ERR is 48%, the maximum share of revenues a company can receive in any given accounting period will be equal to 52% of their working interest share of gross revenues.

A look at the stage

Times are difficult in the exploration business but certainly not dull.

Technology has helped the industry try to keep pace with growing challenges. But, margins are thinner-the kind of contract terms available a generation ago are rare these days-relatively speaking.

This status is not the result of greedy governments, it is the result of an efficient, competitive market. In official license rounds, governments typically award licenses on the basis of the highest bid. It is as simple as that.

In out-of-round situations, the formula is dramatically similar because so many companies are making offers despite increased competition between countries for capital and technology.

Exploration threshold field size requirements have always been robust because of the dramatic risks associated with exploration. But, targets must be even larger for the new megamerged companies. Most countries will not have sufficient potential to attract their exploration capital. Furthermore, many governments are more comfortable dealing with smaller companies. With the exception of ultradeepwater and arctic conditions, exploration will become ever more the domain of smaller independent companies. But it will not get any easier.

References

- Laherre, J., "Production decline and peak reveal true reserve figures," World Oil, December 1997, p. 77.

- Rose, P., "Analysis is a risky proposition," AAPG Explorer, March 1999.

- Johnston, D., "Bonuses enhance upstream fiscal system analysis," Oil & Gas Journal, Feb. 8, 1999, pp. 51-55.

Bibliography

Johnston, D., "Current developments in production sharing contracts and international petroleum concerns," Petroleum Accounting and Financial Management Journal, Summer 1999.

Bush, J., and Johnston, D., "International oil company financial management in nontechnical language," PennWell Books, Tulsa, 1998.

Johnston, D., "International petroleum fiscal systems and production sharing contracts," Course Workbook, 1999.

Johnston, D., "Gas find is mixed blessing overseas," American Oil & Gas Reporter, June 1998, pp. 72-75.

Johnston, D., "Different fiscal systems complicate reserve values," Oil & Gas Journal, May 29, 1995, pp. 39-42.

Johnson, D., "Global petroleum fiscal systems compared by contractor take," Oil & Gas Journal, Dec. 12, 1994, pp. 47-50.

Johnston, D., "International petroleum fiscal systems and production sharing contracts," PennWell Books, Tulsa, 1994.

Van Meurs, A.P., and Seck, A., "Government takes decline as nations diversify terms to attract investment," Oil & Gas Journal, May 26, 1997, pp. 35-40.

Van Meurs, P., "World fiscal systems for oil-1997," Barrows Co., New York.

____"Annual review of petroleum fiscal regimes, 1998," Petroconsultants SA, London.

The Author

Daniel Johnston is an international petroleum consultant with 23 years' experience in the petroleum industry. He has worked in 39 countries conducting oil and gas reserve certifications, field development feasibility studies, evaluating exploration potential of licenses and concessions, and providing expert testimony. He formed his independent consulting practice in 1985. He has advised major and independent oil companies and numerous governments and/or government owned national oil companies in Latin America, Europe, former Soviet Union, Asia, and the Middle East. He has a BS in geology from Northern Arizona University and an MBA in finance from the University of Texas at Austin.