How petroleum firms can shine in ethics debates

Any reader of this article is likely to be someone who makes his or her living from the petroleum industry and have a positive image of it, feeling proud of its achievements and innovations in providing the world with cheap energy.

If you were an ordinary citizen, a user of petroleum products rather than a provider, you would most likely have a more negative image. Here are some of the events that would have helped shape your image of the oil industry:

- The Exxon Valdez oil spill in March 1989, or any of the half a dozen or so larger spills since, all splashed across the media with recurring footage of dead or oiled seabirds.

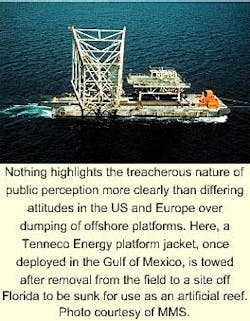

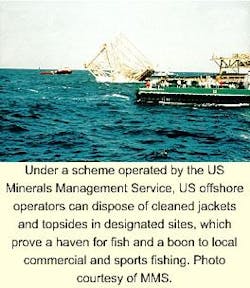

- The public outcry in Europe during the summer of 1995 over the plan by a Royal Dutch/Shell operating joint venture in the UK to dump the Brent spar, an abandoned oil loading buoy, in deep water off northwest Britain.

- The execution by the Nigerian military regime of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other pro-democracy activists in November 1995, and the subsequent questioning of the link between Nigeria's largest foreign producer, Shell, and that country's government.

For ordinary people, not familiar with the positive aspects of the oil industry and unlikely to be informed about them by the nonspecialist media, these stories all showed big oil companies in a bad light. Their impact would have been compounded by the general public's attitude of distrust for big business.

Public attitude

A survey of European attitudes towards corporate investment in social issues by public relations agency Fleishman-Hillard U.K. Ltd., London, was published in June 1999 and showed that consumers support "companies with a conscience."

With business ethics becoming more of an issue for all companies, not just the petroleum industry, and with environmental performance increasingly being seen as a benchmark for companies-all industries, not just the oil industry-the findings of this poll are important.

First, and most critically for all petroleum companies that earn revenues through gasoline stations, the poll of 4,000 people from France, Germany, Italy, and the UK showed that 86% of people prefer to buy products from socially minded companies.

Nine in 10 of the respondents expect companies to use some of their resources to help solve social problems such as unemployment, health issues, and poverty.

Erica Hauver, director of Fleishman-Hillard's community investment practice, said: "This is a wake-up call for business. Companies operating in Europe have frequently hesitated to communicate their good deeds for fear of being seen as exploiting charities or their beneficiaries.

"As long as these investments deliver real value to society, companies are not only safe from criticism, they also have a powerful tool at their disposal for creating more meaningful and lasting relationships with their stakeholders.

"With the credibility of corporations at astonishingly low levels, certainly many companies could benefit from the halo effect generated by social investment. Public expectations are high, but so are the rewards for companies that respond."

Catalysts

Two events overturned the petroleum industry's thinking about ethical issues and how to deal with the public on contentious issues.

Both of these events involved Shell-the Brent spar protests and the deaths of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his fellow activists. In a sense, it was lucky for the general public that Shell was the subject of the outcries; many other petroleum companies would have slammed their doors shut and waited until the fuss over both issues had passed.

Shell surprised the public and the rest of the petroleum industry by having enough heart and enough vision to recognize that something more fundamental than mere anti-company sentiment was underlying the two issues.

Shell recognized that the position of energy companies within society was under scrutiny and would need to change rapidly, if companies are to avoid losing the trust-and consequently the business-of their stakeholders. Stakeholders include not only shareholders and customers but also communities near their facilities and the increasingly vocal environmental and human-rights campaign groups.

Here's how Shell describes its transformation, in a report that set out the thinking which led to a revision of its operating principles: "We were all shaken by the tragic execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight Ogonis by the Nigerian authorities.

"We were ill-prepared for the public reaction to plans to dispose of the Brent spar offshore buoy in deep water in the Atlantic.

"We believe that we acted honorably in both cases. But that is not enough. Clearly, the conviction that you are doing things right is not the same as getting them right. For us, at least, this has been a very salutary lesson."

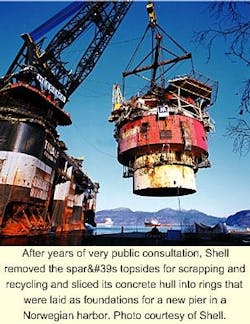

In the end, Shell brought the Brent Spar ashore and dismantled it, recycling much of the structure and cutting its giant concrete hull into rings for use as the foundations for a new quay being built in a Norwegian harbor.

During the process of deciding what to do with the buoy, Shell talked to every interested group it could think of and was completely open about every step. The final disposal cost much more than dumping-more than $70 million compared with an estimate of $18 million. But the extra cost will probably seen as negligible in the long run, because the open debate helped to recover Shell's reputation.

In Nigeria, Shell faced a more intractable problem, but here too the company took an open approach. Through debate with non-governmental organizations and protest groups, the message came through that Shell was not the sinister exploiter portrayed by some parties, but a responsible company with good intentions, operating in an area with immense social and political problems.

Reporting

As a response to the Brent spar and Nigerian issues, Shell took to reporting its health, safety, and environmental performance, setting a standard that few other petroleum companies have even approached. The European uproar over Royal Dutch/Shell's plan to dump the Brent Spar loading buoy at sea was an emotional response and not based on science-in fact, Shell proved that dumping was a better option than onshore disposal when environmental and safety consideration were weighed. The furor took Shell-and the rest of the industry-completely by surprise, but the company used the experience as a starting point for a new attitude toward its operating principles.

This reporting was only part of a total rethink of Shell's ways of doing business, which was overseen by former chairman Cor Herkströter, who retired in 1998.

Explaining the new thinking, Herkströter said, "We believe fundamentally that there does not have to be a choice between profits and principles in a responsibly run enterprise.

"Our plans reach into the very heart of our corporate culture and pulse through the entire organization, in every corner of the world. They are based on our commitment to contribute to sustainable development and the concept of social accountability."

With social accountability increasingly recognized by petroleum companies as a key issue, many companies now report on health, safety, environmental, and social issues, but a recent survey suggested a wide variation in their approaches.

London-based environmental consultant Sustainability Ltd. surveyed the reporting methods of 50 companies with a view to benchmarking the industry's performance in reporting of its impacts.

Shelly Fennell, director of Sustainability, said that environmental and social reporting is well entrenched among the bigger companies: "Of the 50 chosen companies, 34 had published an environmental report.

"Surprisingly, some companies that we did not think were under great shareholder pressure fared particularly well. We found quite a lot of good work out there, but it needs to be pulled into a coherent whole."

Fennell found that larger companies were generally adopting environmental and social reporting as standard practice, although small companies, exploration and production companies, state-owned firms, and project-based consortia often lagged behind.

Much of the disclosed data was quantitative, comprising inputs and outputs of products and pollutants, reports of accidents and spills, listings of environmental spending, and management policies.

"What we would have liked to have seen," said Fennell, "was an indication of the extent to which companies are moving towards making cleaner transport fuels.

"We would have liked to have been given an idea of what percentage of their output was renewables. Also, we would have liked to have seen some measure of the disturbance to land and biodiversity by company operations."

Sustainability found two major problems with the industry's environmental reporting: a lack of clarity within individual reports over what the data covered, and a lack of comparability between company reports.

"We recommend strongly that the industry adopts a standard reporting method," said Fennell. "This needs to be done in two parallel ways: companies should provide a full set of indicators of performance; and they should highlight a core set of 5-10 indicators for benchmarking across companies.

"We have recommended broad categories for a best practice framework, but we are not best-placed to decide what the indicators should be. Some inter-company benchmarking is being developed, and we recommend that these models be incorporated into the framework. Importantly, the industry leaders should exert pressure on their peers."

Taking action

Fine promises mean nothing if they are not put into practice. Shell is working towards sustainable development through its Shell International Renewables division, for example, which is building solar power and biomass projects in developing countries-and making money from them.

BP Amoco PLC also is keen to demonstrate that it is taking practical steps towards improving the environment. BP Amoco Chief Executive John Browne believes that petroleum companies should work towards giving society a better choice than the increased material wealth equals worse environment dilemma that many people see as inescapable. He feels petroleum companies should work towards reducing emissions-and not just dabble in green issues to create a little public relations gloss.

Under one initiative BP Amoco in June 1999 took a step ahead of any other company towards reducing its own greenhouse gas emissions to 10% below 1990 levels by 2010, by sanctioning an independent audit of its greenhouse gas emissions.

The company commissioned a team from London-based KPMG and Det Norske Veritas and ICF Consultants Inc., Washington, DC, to check its accounting and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

The audit team began by reviewing BP Amoco's greenhouse data for 1998 and aimed by the end of 1999 to have the mechanisms in place for the industry's first greenhouse gas emissions audit process, in line with international financial and environmental auditing standards.

A KPMG official said that BP Amoco intends this audit process to become a template on which the industry as a whole can base its greenhouse gas monitoring programs: "The process will be completely open so that other companies can lift these ideas."

A key part of the auditing mechanism was to be the monitoring of an internal pilot greenhouse-gas emissions permit-trading system, which BP Amoco started in September 1998 and aims to have introduced worldwide during 2000.

Under this program, the business units of BP Amoco worldwide that are able to reduce emissions at a relatively low cost can sell excess emissions "credits" to units with high emissions-reductions costs, as they all strive to meet the corporate reduction target.

Advice

While some petroleum companies have woken up to the growing relationship between ethical behavior and the bottom line, many more are in denial.

Geoffrey Chandler, chairman of Amnesty International UK Business Group and former senior Shell executive, addressed this problem in an article he wrote for the UK's Green Futures magazine.

"For many of the issues involved, though not all," said Chandler, "we know what to do to make the sustaining of economic rights compatible with the sustaining of civil, political, social, and cultural rights.

"Why then do the transnational companies-some of the most sophisticated of organizations-require damage to reputation or a long attritional battle to force change? There are several factors. The insulation of top management, for one. Breadth of vision and open-mindedness tend to go in inverse ratio to hierarchical status. Perception and understanding of the real world are narrowed by the company car and chauffeur, the private plane, and the corporate palaces that isolate top executives. From this viewpoint, the corporate instinct is to rebut, to look to public relations as a defense, not to change."

At a more fundamental level, however, Chandler attributes some of the blame to the definition of the purpose of a company. In this view, while the limited liability company is the most successful vehicle for harnessing capital, skills, and technology to a given end, any company that believes its long-term purpose is only to maximize value to shareholders is blinkered.

Both Shell and BP Amoco have recognized the existence of a broader group of people that must be satisfied by a successful company's actions: stakeholders-that is everyone affected by a company's operations, of which shareholders form only a part.

"Satisfying shareholders is a condition of survival," said Chandler, "not a purpose. And it's a hopeless guide to ethical behavior for practicing managers in the real world.

"Most thoughtful managers would define the purpose of a company as being to provide goods and services profitably and ethically. It is a purpose that recognizes the existence of stakeholders-on whom it depends for its success and affects through its operations.

"The concept of stakeholders points the way to determining the frontiers of corporate responsibility and offers a guide towards the criteria and measurement of performance relevant to each of them."

The Author

David Knott is Associate Chief News Editor of Oil & Gas Journal and writes the magazine's weekly Watching the World column.