Venezuela Hatching Big Plans For Jump-Starting Natural Gas Sectorl

The aggressive development of Venezuela`s huge natural gas resources is one of the highest priority objectives of the new administration of Hugo Rafael Chávez Frias.

During the electoral campaign of 1998 and at every opportunity since his government has taken office this year, Chávez has insisted that he will do everything necessary to facilitate the growth of the gas, petrochemical, electricity, mining, agriculture, and tourism sectors. So it was no surprise that, on June 17, Alí Rodríguez Araque, the new Minister of Energy & Mines (MEM) announced that Petroleos de Venezuela SA`s (Pdvsa) new business plan for 2000-09 envisages Venezuelan gas production at roughly 14.5 bcfd in 2010, which represents an increase of slightly less than 2 bcfd over the prior 10-year plan. Venezuela currently produces about 6 bcfd. Venezuela is now serious about natural gas.

Background

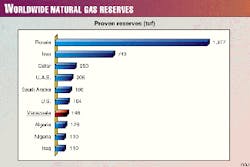

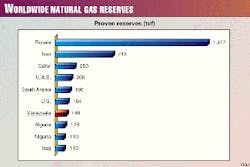

Venezuela`s proven reserves of natural gas stand at 146 tcf, the sixth largest in the world (Fig. 1). It is estimated that a further 45 tcf and 36 tcf represent, respectively, probable and possible reserves. However, as Fig. 2 shows, the huge majority of Venezuela`s gas reserves is associated with oil; only about 9% of the total is nonassociated gas.

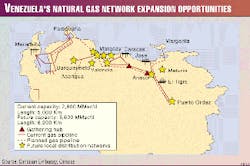

In addition, most of Venezuela`s gas reserves lie in the eastern half of the country. Venezuela has two separate gas pipeline systems-one in the West and the other in the East. Joining the systems would represent a major infrastructure project-which is in the planning stage. Venezuela boasts about 5,000 km of gas pipelines, with a capacity of around 2.6 bcfd.

Considerable demand for gas exists in the West. Major customers for gas include the Complejo de Refinación Paraguana (which includes the Amuay and Cardon refineries), the El Tablazo petrochemical complex, and major electric utilities.

On the other hand, there exists virtually no commercial production of nonassociated gas in Venezuela today. It may well be that, given the heavy use of associated gas in oil operations, actual disposable gas for sale could be less plentiful than the huge reserve figures would suggest.

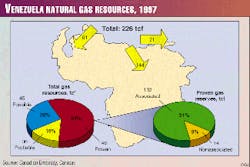

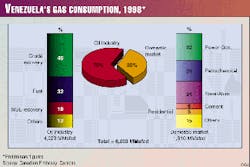

Of Venezuela`s 6 bcfd of gas production, over 70% is used for gas injection, gas lift, as operations fuel, or for other operations-related purposes. About 30% goes to the domestic market, where the main users are power generators (32%), petrochemical plants (21%), and steel/aluminum producers (21%). Residential demand stands at a tiny 5% (Fig. 3).

Natural gas accounts for approximately 20% of Venezuelan electric generation, with hydroelectric supplying over 70%. Although gas prices are subject to regulation by MEM, it is possible for producers and industrial customers to agree to higher prices in the case of medium to long-term sales, if MEM approves.

Apart from the fact that most Venezuelan gas is associated gas-and hence is produced as a result of, and is needed for, oil operations-a number of other factors account for the relatively small size of the Venezuelan domestic market for gas:

- The legal regime for gas has been and remains chaotically unclear.

- Prices for gas have been regulated for decades at rock-bottom prices.

- Gas production is subject to a royalty of 16.66% and an income tax of 67.7% levied against profits.

- Venezuela has developed significant hydroelectric power, which competes with gas as an alternative energy source.

- Until recently, the transportation and storage of gas was considered a state monopoly activity, and private equity capital was excluded-therefore markets were not developed.

- Venezuelan industry in general has remained relatively undeveloped, and the petrochemical industry, a major potential customer for gas, has not grown vigorously.

- The electric power sector, another natural customer for gas, is little regulated, state-dominated, and stagnant, with decaying infrastructure and heavily subsidized prices.

Beginning of change

Prior to Jan. 1, 1976, the Venezuelan oil industry was managed on a concession basis, under which private companies explored for and produced hydrocarbons, paying royalties and tax to the government in Caracas.

After nationalization, Pdvsa acquired all of the rights of the former concessionaires. Under Articles 1 and 2 of the Nationalization Law, known by its Spanish acronym Loreich1, Pdvsa was granted monopoly rights over the exploration, production, transportation, storage, refining, exporting, and retailing of all hydrocarbons, including gas. Pdvsa, however, has been formed and run as a commercial enterprise, even though it has a single shareholder-the state, through the MEM.

In the 1990s, it became plain that Pdvsa did not have the capacity, on its own, to take advantage of its massive business possibilities. Thus began the process of apertura (opening), which has led Pdvsa to seek international-and to a lesser extent, national-partners to develop offshore dry gas as LNG (Cristobal Colón); explore for and produce light and medium crudes (the exploratory rounds); to produce, transport, and upgrade heavy crude from the Orinoco oil belt (Petrozuata, Sincor, Cerro Negro, and Hamaca projects); to reactivate nonproducing or underproducing oil fields (the first, second, and third marginal fields reactivation rounds and the Boscan project); to carry out major outsourcing projects such as Pigap I and II (gas injection), the Maracaibo water injection project, the Jose terminal (oil storage and shiploading), Accro III & IV (natural gas liquids extraction), and the list goes on.

In addition, Pdvsa and the new private players have generated a vast market for all kinds of oil-related equipment and services. The Venezuelan apertura unquestionably represents the major policy initiative of the government of Rafael Caldera (1994-98), although the process itself had began earlier, arguably in 1989.

However, during the bitter election campaign of 1998, Caldera`s oil policies came under attack from Chávez on grounds that the apertura discrimated against Venezuelan firms and would serve to drive down world oil prices, without positively affecting the overall Venezuelan economy. The critics demanded the development of gas, petrochemicals, and Venezuelan refining.

Despite these criticisms, the Caldera government must be given credit for launching its own gas initiative, which is the precursor of the much more ambitious Chavez gas program. First of all, the Caldera administration enacted pricing resolutions that seek to achieve a situation in which methane prices in western Venezuela would be tied to the price of the cheapest alternative fuel and in which prices in eastern Venezuela would rise to reflect the marginal costs of long-term development. And there exists an "approved rate" exception to those mentioned above.2

In addition, the Caldera administration developed an important legal interpretation of Loreich and other laws applying to gas that effectively took the midstream and downstream sectors of the gas business out of the restrictive coverage of Loreich. MEM`s argument was that, because methane and ethane always need to be "processed out" of the raw associated gas that appears at the wellhead, methane and ethane count as "refined products" and hence are subject to the much more liberal provisions of the 1973 Law on the Internal Market.3 MEM, relying on the authority of the latter law, laid a basis for a new transitory midstream and downstream gas regime by enacting the short Decree 2532 of May 20, 1998, with the more detailed Resolution 323 of Nov. 13, 1998, following up to provide a convincing, if temporary, regulatory framework, allowing for the inclusion of private entrepreneurs in most branches of the gas business.

On the other hand, these regulations could not annul or rationalize the maze of conflicting legislative provisions, dating from various eras, that litter the landscape of the Venezuelan gas business. The table names the principal legislation that now regulates or significantly impacts the gas industry4.

The Venezuelan gas industry needs wholesale reform, with the goal of fostering an investment model that will include foreign private, domestic private, and state players.

Chavez administration policy

The Chavez administration wishes to maximize the production and use of gas in Venezuela and for export. The government envisages Venezuela building a modern, environmentally sound industrial base through plentiful cheap gas and cheap electricity. At the same time, it wishes to ensure that Venezuelan businesses, individuals, and capital will be involved in and will benefit from this gasification process. It wishes to encourage exports of gas, whether by way of pipeline or LNG, and to foster Venezuela`s indigenous petrochemical industry.

All the signs are that this government realizes that the Venezuelan gas industry must be developed principally by the private sector. The government will encourage this process even at the ostensible expense of national and municipal tax revenues.

Upon attaining office, Chávez appointed a high-level gas project team, which has undertaken a detailed review of many of the world`s advanced gas legal systems, including Argentina, Canada, the U.S., Norway, Spain, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and Colombia. Critically, the government was able to obtain a ley habilitante (enabling law) from the Venezuelan Congress in April, which was signed into Law by the President on Apr. 26. The enabling law gives the President fast-track authority to legislate on defined areas via decree law. Such decree laws require no further approval by Congress. Among many other important items, the enabling law gives the President power to issue a new Organic Gas Law (OGL). Because the new law will be "organic," it will be Venezuela`s controlling authority on the gas business and will be legally superior to all previous laws.

At an early stage, the new Venezuelan government decided to create a legal regime that would liberalize the exploration and production of nonassociated gas and that would govern the pricing, transportation, storage, distribution, commercialization, and exporting of all gas, whether such gas is to be produced in free or associated form. The enabling law envisages that the new OGL will create such a regime5. The production of associated gas, however, will for the meantime be governed by Loreich. But the intention of the Chavez administration is to replace Loreich with a new umbrella hydrocarbons law. No reform of the gas sector would be complete without a transformation of the electricity sector. That, too, is provided for in the enabling law6.

New natural gas regime

A new OGL is currently being prepared in accordance with the gas provisions of the enabling law. A first draft is not yet available for public comment, but the principal provisions are likely to include the following:

Associated gas

The exploration and production of oil and gas will continue to be regulated under Loreich until such time as a new hydrocarbons law is enacted. Clearly, the associated gas sector will remain a critical factor in the development of Venezuela`s oil production.

Gas injection is so critical a feature of the Venezuelan oil industry that it will inevitably continue to generate major economic activity in its own right.

For example, the El Furrial injection project, Pigap II, and Accro III and IV are of this variety. Further major associated gas outsourcing projects are likely, given that Pdvsa finds it necessary to invest so much in production infrastructure.

Possible operational developments

The OGL will likely serve as the basis or stimulus for several business initiatives, which should occur thereafter.

Various new pipeline projects within Venezuela are being considered (Fig. 4). One project would unite the eastern and western pipeline systems. Another would pipe gas from the eastern oil fields over to the island of Margarita. This would require the construction of a 200-km pipeline, with about 60 km subsea. A significant expansion of domestic distribution systems is planned for major cities, such as Valencia, Maturin, Maracay, and Barinas.

Pdvsa Gas SA currently owns Pdvsa`s midstream and downstream gas assets, such as pipelines, distribution systems, etc. Many of these facilities need expansion, refurbishment, or maintenance. Pdvsa Gas will seek the means to attract private capital to assist in carrying out these tasks, with the objective being to provide private investors with full equity in the projects. It is not yet clear as to how this will be achieved.

It is probable that certain areas with a high likelihood of holding dry gas reserves will be put out for licensing. This will probably be done on a project by project basis rather than as a licensing round.

Final thoughts

The administration must be commended for its determination to jump-start Venezuela`s Cinderella gas business. There is every reason to believe that the new OGL will create a modern, legally secure framework for a market-oriented gas business. In time, the economy will generate greater demand for cheap and available energy and for chemical feedstocks. In this context, the gas business will assume critical importance. Similiar positive scenarios occurred in Argentina and Trinidad and Tobago, to name but two examples.

The key to short-term investment flows, however, will relate to who will buy available gas "tomorrow" and at what price. Pricing strategies are not yet clear. In addition, will the new law on electricity make it attractive to sell gas-generated electricity to the national grid, or will new gas-to-power investment only be feasible for off-grid customers? Other critical factors will be the short-to-medium term world demand for petrochemicals and Latin American demand for gas products. And how easily will emerging-market countries find it to finance gas projects over the next year or so?

Overall, foreign and domestic investors should be encouraged that this Venezuelan government is willing to create a workable framework for gas in Venezuela for the first time. The Venezuelan gas project looks promising, but many questions remain. Answers will no doubt become forthcoming shortly.

References

The Authors

Uisdean R. Vass is a partner in Macleod Dixon, an international law firm headquartered in Calgary and with offices in Caracas, Moscow, Almaty, and Toronto. Vass is based in the Caracas office, Despacho de Abogados miembros de Macleod Dixon SC. He holds an LLB (Honors) from the University of Edinburgh Faculty of Law in Scotland and an LLM (with specialization in oil and gas law) from Louisiana State University Law School in Baton Rouge, La. Vass is licenced to practice law in Scotland and Louisiana and holds a special permit to practice international law in Venezuela.

Ruben Eduardo Lujan is a senior associate with Despacho de Abogados miembros de Macleod Dixon SC. He holds a cum laude law degree from Universidad Catolica Andres Bello (Caracas) and an LLM from the University of Michigan Law School in Ann Arbor, Mich. He is admitted to practice in Venezuela and is a member of the Caracas Bar Association and the Section on Business Law of the International Bar Association.