Russian Far East Holds Huge Resource Potential

About this report...

Investment in the Russian Far East remains lukewarm, despite the area`s tremendous resource potential. Not only are foreign investors cautious, but economic and political problems throughout Russia continue to hamper economic development.

Nevertheless, the Sakhalin-II consortium, consisting of Marathon Sakhalin Ltd., Mitsui Sakhalin Development Co. Ltd., Shell Sakhalin Holdings B.V., and Diamond Gas Sakhalin B.V. (Mitsubishi), will become the first group this month to achieve production under terms of a Russian production sharing agreement (PSA).

Yet Sakhalin gas-pipeline economics continue to suffer, with Gazprom losing an estimated $13/1,000 cu m. Unfortunately, the Russian government will likely regulate gas price levels below delivery cost for the next several years.

Rounding out the report are articles on the Far East`s political structure and a feasibility study about the neighboring Verkhnechonsky field in the Irkutskaya Oblast.

The Russian Far East, an economic zone located between the Pacific Ocean, East Siberia, Arctic Sea, and China, contains huge deposits of untapped petroleum, coal, and other mineral resources that await economic development by Russian and foreign companies.

Unfortunately, demographic, economic, and political problems continue to hamper development of these deposits.

Demographics

The Far East Economic Region of Russia has an area of 6.21 million sq km, making it two-thirds the size of the U.S. With a population of 8.35 million, most of its people live along the Trans-Siberian Railway, a major transportation route that meanders along the southern fringe of the Russian Far East, hugging the border with China.

The largest towns are Vladivostok with 688,000 people, Khabarovsk with 650,000, and Komsomolsk with 350,000. No other settlement claims more than 300,000 people.

Its remoteness from the rest of Russia, along with its hostile climate, made the Russian Far East the perfect location for the exile of convicts and political prisoners over the centuries. It acquired a strategic military importance during the Cold War years with the construction of numerous naval and air force bases.

Since the mid-1970s, the Far East has been seen as an economic window on the Pacific Rim with successive Russian leaders hoping the region would serve as a catalyst for the economic development of the rest of Russia.

Paradoxically, there have been problems associated with the development and distribution of these resources, placing an economic damper on development. This is especially true in the northern and eastern parts of the region where the mineral wealth is concentrated. Road and rail links with the southern fringe, and hence the rest of Russia, are nonexistent. And for the most part, mining communities can be reached only by water for several months a year, or by air.

Power and coal

The traditional method for providing this region with energy was through the installation of hydro stations, such as the 1,200 mw Zeya and 720 mw Kolyma power plants. New hydro stations planned before the break-up of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the Russian economy included the Bureya (2,000 mw) and Adycha (500 mw) plants.

Over the years, ambitious plans for nuclear stations have been drawn up, but have never materialized, apart from the tiny 48 mw Bilibino station located in the extreme north of the Far East.

Coal

The Far East contains huge reserves of coal, although most of it is located beyond economic accessibility in the Lena basin, with deposits approaching 1,800 billion metric tons (metric units used hereafter). Much smaller fields lie conveniently along the Trans-Siberian Railway but consist mainly of poor-quality brown coal.

The biggest producer is the Bikin field in Primorsky Krai. Coal from this field fuels the 990 mw Primorsky power station at Luchegorsk.

Unfortunately, the energy strategy based on the development of coal resources has not proved highly effective in the 1990s. The main consumer of electricity, the government, has failed to pay for its energy use, so the power stations have been unable to pay the coal companies, who in turn, have been unable to pay wages to their workers.

Strikes, riots, and power cuts by coal miners have forced the government to periodically provide cash grants. After passing through the hands of banks, however, these monies frequently got lost on the way.

The first of a number of projects planned during Soviet times to tie the Russian economy into those of the Pacific Rim countries included the South Yakutsk coal field development project at Neryungri, located in the republic of Yakutia (Sakha Republic).

The coal is of high quality and can be strip mined. A 1974 Soviet-Japanese agreement gave rise to a mine capable of yielding 13 million tons/year, including 9 million tons/year of coking coal destined for Japan, and a railway line connecting the mine with the Trans-Siberian Railway.

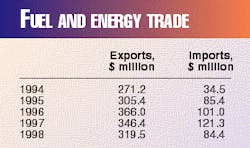

The Neryungri coal development has enabled the Far East region to export over $300 million/year of fuel despite its own fuel shortages (Table 1). Russia has been exporting 5 million tons/year of coal to Japan in recent years, mostly Neryungri coking coal. Oil products imported from China, South Korea, and Japan account for most of the fuel imports.

Oil and gas reserves

The Far East also has considerable reserves of oil and gas. A+B+C1 (roughly proved + probable, OGJ, Oct. 5, 1992, p. 102) reserves at onshore fields are calculated at 80 million tons of oil and condensate in Yakutia and 30 million tons on Sakhalin Island. Reserves comprised of the C3+D (roughly potential + hypothetical) category amount to 1,220 million tons of oil and 420 million tons of condensate.

The region is credited with 1.13 trillion cu m of proved + probable gas from a Russian total of 49 trillion cu m. This consists of 271 billion cu m of methane gas and 859 billion cu m of gas with an ethane content exceeding 3%. There are C3+D reserves amounting to 7.44 trillion cu m, nearly all of it in Yakutia.

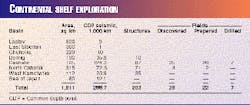

Marine reserves tend to be much larger. The C3+D reserves of oil amount to 780 million tons in the Sea of Okhotsk and 2.03 billion tons in other sectors of the Far East Shelf. Condensate reserves are 150 and 650 million tons, respectively. Gas reserves are 3.84 trillion cu m in the Sea of Okhotsk and 2.64 trillion cu m in other areas of the shelf.

These data relate to the end of 1994, but because of the negligible amount of seismic work and the small number of potential structures identified since then, it is unlikely to have changed by much (Table 2). The seismic work was undertaken by the Dalmorneftegeofizika subdivision of the Morgeo marine geophysical enterprise, based in the town of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk.

The drilling work, encompassing seven prospects, was carried out by Rosneft`s Sakhalinmorneftegaz subsidiary. These include the Lunskoye, Odoptu-More, Piltun-Astokhskoye, Veninskoye, Chaivo, and Arkutun-Dagi fields located off the east coast of Sakhalin Island and the west coast of Izylmetyevsk. Since 1994, Kirinsk has been added to this list.

Current activity

Despite the calamitous decline in exploration activity in Russia since 1990, a small amount of work is still taking place. In May 1996, a new oil field with 60 million tons of oil was found beneath Lake Orel in the Kulchi Region of the Khabarovsky Krai, located 365 km north-northwest of Komsomolsk city.

The field was found by the Dalgeo enterprise, working under contract to Komsomolsk Oil Refinery.

Small amounts of oil have been found over the years in the Primorsky Krai, mainly at Artem, Dalnerechensk, and Luchegorsk. Local geologists say the province could contain 100 million tons of recoverable oil.

Small oil shows have been found in the Anadyr area of the Chukotkskaya Okrug and the local administration has signed an exploration contract with Lukoil Oil Co.

In addition to the well-known Sakhalin offshore projects (see related story, p. 44), the Russians have also signed agreements with foreign companies for the exploration of other promising areas. In 1996, state-owned Sakhaneftegaz of Yakutia signed a contract with Japan National Oil Corp. and Exxon Corp. for the exploration of the northeastern part of the Nepsko-Botuobinsk oil region in southwest Yakutia. Exxon had already signed agreements to explore the central Nepsko-Botuobinsk and Vilyuisk regions.

Oil production began on Sakhalin Island from the Okha field in 1923, but more than half of the island`s 1.5 million ton/year output now comes from the Mongi area. Only the Mongi and Okha fields have a significant economic impact, with most of Sakhalin`s oil coming from a large number of very small fields.

At the end of 1996, there were 2,414 oil and gas wells on Sakhalin Island, of which 1,712 were operational. Only 57,000 m of development wells were drilled in 1996 and about 30,000 last year.

Gas production in Yakutia comes from the Ust Vilyuisk and Mastakhskoye fields, discovered in 1956 and 1966, respectively. The much larger Sredne-Vilyuisk field was found in 1963 and began producing in 1975.

All these fields are located in the Vilyui River valley, and the gas is exclusively piped to Yakutia`s capital city, Yakutsk. Reserves are sufficient to justify the construction of a pipeline from Yakutia to China and Japan, and there has been a plan since the mid-1980s to do so. However, no one is willing or able to find the money for its construction.

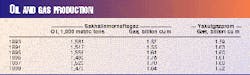

Yakutia`s Irelyakhneft Enterprise, Mirnyi, also produces 23,000 ton/year of oil from the Irelyakh oil field. A tiny amount of condensate is produced in Yakutia and processed by Yakutgazprom with volumes falling from 78,000 tons in 1994 to 64,000 tons in 1996 (Table 3).

Sakhalinmorneftegaz began marine oil production for the first time in August 1998 when a directional well drilled from the shore into the northern part of Odoptu-More field yielded 230 ton/day (Table 3). The angle of inclination was 84°, and the well reached a depth of 1,506 m. The southern part of this field is to be developed under the Sakhalin-I project.

Sakhalin pipeline

Oil produced on Sakhalin Island is pipelined over a distance of 580 km to the Komsomolsk oil refinery on the mainland. The pipeline runs 180 km across Sakhalin Island to the west coast at Pogibi, then traverses 20 km across the Nevel Straits to Lazarev, finally reaching Komsomolsk via De Kastri over a distance of 380 km (see related story, p. 60).

The pipeline, built in the 1940s, has been described by Russian experts as "lamentable."

A gas pipeline follows the same corridor, while the construction of a 50-km extension from Komsomolsk to Amursk began in 1997. It is the first stage of a 985-km line that will eventually run to Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. It should be completed in time for the first deliveries of gas from Sakhalin`s offshore fields.

Of the 3.16 billion cu m of gas produced throughout the Russian Far East in 1998, 1.9 billion cu m was burned in small power stations with most of the rest piped to households.

There is very little industrial use of gas in the region. In the main province of Primorsky, gas-mainly bottled and supplied to households-accounts for 31.3% of total fuel consumption.

Oil refineries

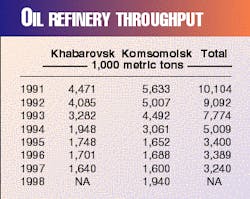

The Far East has two major oil refineries, at Khabarovsk, belonging to Sidanko with an effective capacity of 4.7 million tons/year, and Komsomolsk, belonging to Rosneft with a capacity of 5.4 million tons/year (Table 4).

At the beginning of the 1990s, these plants were operating at or above their effective capacities, but are now processing less oil than is economically worthwhile.

Komsomolsk processes all the oil produced by Sakhalin`s onshore fields. It is delivered through the Okha-Komsomolsk pipeline.

During the 1980s, the refinery also processed 4 million tons/year, transported through 2,100 km of pipeline from Western Siberia to the eastern terminal of the Trans-Siberian Pipeline at Angarsk, and then for another 3,000 km by railway to the refineries.

The supply of this oil to Komsomolsk has now dried up, and Khabarovsk remains dependent on Western Siberian crude. The delivered cost of the crude, and hence oil products refined from it, is therefore extremely high, especially because the rail tariff for transporting crude from Western Siberia was increased to $55 a ton.

Locally refined products are thus unable to compete on the domestic market with imported products, mainly gasoline from China, Korea, and Japan. There is a potential market of 8 million tons/year of gasoline and diesel in the Far East.

The oil refineries have been paying the Ministry of Railways with oil products rather than cash; however, the Ministry stopped this practice in September 1998, demanding cash for its services. The refineries could not pay, and because they are entirely dependent on Siberian crude supplied by railway, the Khabarovsk refinery was forced to close for a time.

The Sakhalin-I and Sakhalin-II projects were initially expected to provide Russia with a share of 7 million tons/year of oil by 2002. The government assumes that all this oil will be exported.

The crushing shortage of oil products in the region, however, has prompted a number of experts to ask whether the crude can be refined at the Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk refineries, enabling them to operate at full capacity.

While most of the output would be destined for the domestic market, the cost of modernizing the refineries must be met by the export of products. A project for the modernization and expansion of the refineries was drawn up and approved by the Russian government in May 1994.

The Komsomolsk refinery was built in 1935 and expanded in the early post-War years. It is extremely inefficient with virtually no secondary refining plant and an average depth of refining of 54%, poor by even Russian standards.

While it is possible to export up to 0.3 million tons/year of oil from the Moskalvo port, located on the northwest corner of Sakhalin Island, Sakhalinmorneftegaz is otherwise completely dependent on Komsomolsk for its refining needs.

The modernization project will be extremely expensive, with the reconstruction of Komsomolsk alone estimated at $700 million. Neither the Russian oil companies nor the government is prepared or able to spend this sort of money, and several contracts have been signed with foreign companies.

In 1994, Totisa of Ecuador and a consortium of Japanese companies won contracts worth about $30 million to install equipment for the production of 93 and 95-octane gasoline at Khabarovsk, according to the refinery`s Director, Nikolai Shalavin.

According to Russian sources, Mitsui, one of the members of the Sakhalin-II consortium, intends to refine its share of oil output at Komsomolsk with the subsequent distribution of oil products in Russia and the Pacific Rim countries.

Komsomolsk`s modernization program had two stages. The first stage, from 1997 to 1999, anticipated the refining of 3 million tons/year of oil, half from Sakhalin and the other half from Western Siberia, with the simultaneous construction of three new facilities.

These included a 300,000 ton/year catalytic reformer, a 600,000 ton/year visbreaker, and a 1 million ton/year hydrotreater. The hydrotreater can produce diesel with a maximum sulfur content of 0.05 wt %.

Capital costs of $100 million were to be recouped in less than 3 years while raising the refinery`s average refining depth from 56 to 73%, thereby raising the output of gasoline and diesel by 510,000 tons/year to 2.2 million tons/year. This first stage was discussed by Rosneft`s Council of Directors as recently as February 1997, but nothing came out of it.

The second stage, from 1998 to 2002, expected an increase in throughput to 6 million tons/year, consisting of 5 million tons/year of Sakhalin oil and 1 million tons/year from Western Siberia.

There are plans to build a 1.3 million ton/year hydrocracker, a new 2.5 million ton/year primary refining unit, and a 30,000 ton/year bitumen plant. The catalytic reformer capacity will be more than doubled to 800,000 tons/year and the capacity of the visbreaker raised to 1.1 million tons/year.

A 200,000 ton/year base lubricant plant will also be built, using feedstock from the hydrocracker. The second stage will cost $600 million and is expected to be recouped in 6-7 years. This stage will increase the refining depth to 81%, implying a light product yield of nearly 4.9 million tons/year by 2002.

While no work has yet been carried out according to these plans, they have not been scrapped and it must be assumed that they will be undertaken when financing becomes available.

Komsomolsk`s Technical Director, V. Yezhov, expected the Japanese companies to provide the money for both phases of the modernization program. Mitsui, Marubeni, Nichimen, Nissho Iwai, Sumitomo, Chiyoda, and other companies were said to have expressed an interest in participating in the engineering work.

During 1995, the Komsomolsk management held discussions with potential Japanese partners. Totisa of Ecuador was also involved in the Komsomolsk project at one time. It was hoping to reach an agreement with Rosneft to drill oil wells on Sakhalin for the supply of additional feedstock to the refinery.

In October 1996, discussions were resumed with Mitsui, Nichimen, and Marubeni. The talks with Mitsui were said to be "the most constructive" and resulted in the signing of a protocol of intent for the implementation of the first phase.

During the discussions, Komsomolsk officials assured Mitsui that contracts for the export of oil products from Russia would be concluded with those companies that participate in the modernization program.

Mitsui said that it would start refining its share of Sakhalin-II oil at Komsomolsk as early as 1999. The work was to be undertaken on a turnkey basis with Toyo Engineering employed as contractor. The money was to be obtained from credits already extended to Russia by Mitsui and guaranteed by Japan`s Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

The Khabarovsk refinery was built in 1950, claiming a refining depth of 70.8%, well above the Russian average. It is unlikely that Sidanko will spend much on reconstruction as long as its performance is respectable by Russian standards.

There is also a small 300,000 ton/year oil refinery operated by the Petrosakh joint venture at Pogranichnoye on Sakhalin Island. It is designed to process oil from the Petrosakh`s Okruzhnoye oil field, discovered in 1984. This field holds 25 million tons of recoverable reserves and began producing in 1995. It is located on the east coast of Sakhalin, 145 km southeast of Aleksandrovsk.

From time to time, plans arise for the construction of new refineries in the Far East region. The administration of Primorsky Krai is considering the construction of a 2 million ton/year plant which will meet 25% of the province`s demand for oil products.

A driving force behind the plan is the Primorskugol enterprise, which operates the coal mines in the province. Although they claim to be bankrupt and unable to pay wages to their workers, Primorskugol says it can finance 80% of the $315 million refinery and only needs a further $63 million from foreign banks.

Although this sounds unlikely, it was approved by the Russian government`s Emergency Commission for the Fuel and Energy Complex of the Far East in December 1996. By this time, the projected cost had risen to $1 billion and the Mayor of Vladivostok, Viktor Cherepkov, says it will be built by Lukoil.

In 1998, the Primorsky administration acquired land from the Ministry of Defense at Bolshaya Kamen for the construction of a 4 million ton/year refinery, dedicated to processing oil from the Sakhalin offshore projects. The administration also has plans for a 0.8 million ton/year gas liquifaction plant and a tanker terminal at Razboinik Bay to process Sakhalin gas.

Marketing

The principal distributor of oil products in the Far East is Rosneft`s Nakhodkanefteprodukt enterprise based in Nakhodka. Rosneft has also set up a Dalrosneft joint stock company whose main shareholders include the Rosneft subsidiaries Sakhalinmorneftegaz and Komsomolsk oil refineries.

Lukoil supplies the isolated coastal settlements of the Chukotkskaya Okrug in the far northeast through its Lukoil-Arktik-Tanker subsidiary using three 16,000 dwt tankers. Kamchatka`s peninsular region imported oil products, mainly from China, until it could no longer afford to pay for them, and is now supplied by Rosneft.

Sidanko`s Magadannefteprodukt supplies the Magadan Province with petroleum products, but it plans to draw BP Amoco plc into the development of onshore and marine oil fields in addition to the construction of an oil refinery near Magadan City. Nevertheless, these projects are unlikely to succeed.

The Far East has the highest consumption of diesel and gasoline per person in Russia, basically because of the comparatively long average journeys undertaken by the freight transport sector. Trucks account for 40% of freight transport while the railways and coastal shipping share the rest.

With 8.5 million people, the Far East had only 606 filling stations as of October 1996 and the retail price of oil products was nearly twice the national average.

Company turmoil

Foreign companies hoping to exploit the oil and gas resources of the Sakhalin Shelf must deal with the local oil producer Sakhalinmorneftegaz, which is 51% owned by the state-owned oil company Rosneft. The rest of the shares are traded on Russian stock markets, although infrequently.

Dividends have never been paid on ordinary shares. The company employs 13,700 workers and has one of the lowest labor productivities of all oil production enterprises.

Sakhalinmorneftegaz`s finances are in reasonable shape because it is able to export most of its output. In 1996, it exported 0.93 million tons from output of 1.49 million tons. In fact, this exported oil is processed at Komsomolsk on the accounts of other oil companies while these companies export oil through the Druzhba export pipeline to Eastern Europe on a mutual-account basis.

The government transformed Rosneft into a joint stock company in September 1995, with 34 subsidiaries and 70,000 employees. It is one of the smaller, vertically integrated Russian oil companies, accounting for 4.3% of oil production, 5.2% of exports, and 2.6% of refinery throughput.

Rosneft was cobbled together from the small oil producers and refineries that none of the larger companies wanted, including the Purneftegaz enterprise of Western Siberia. This enterprise accounts for over 65% of Rosneft`s crude output, effectively keeping the company afloat. The other members, apart from Sakhalinmorneftegaz, are tiny producers in the North Caucasus Region.

Rosneft holds licenses, however, for the largest oil fields on the Sakhalin shelf, with ultimate oil and gas reserves estimated at 4 billion tons. The company also has a share in the ownership of 1 billion tons in the Arkhangelskaya Oblast.

Rosneft argues that its resource base makes it the fourth-largest oil company in Russia and the fifth largest in the world. Unsurprisingly, there has been a political power struggle for the top jobs in the management of Rosneft.

In April 1997, the Chairman and President of Rosneft, Aleksandr Putilov, was dismissed by former Prime Minister Chernomyrdin and replaced by Yurii Bespalov, a former Minister of Industry.

This raised a furore in the company, although it owned 100% of Rosneft. This is because the government could not legally dismiss Putilov, and the company`s first Vice-President, Rair Simonyan, hinted that Putilov had to leave to make way for a friend of the former Minister of Fuel and Energy, Boris Nemtsov.

When the government remembered that Rosneft was the first company to obtain foreign credits, said to total $500 million, without a Russian government guarantee, Chernomyrdin rushed out a new decree canceling Putilov`s dismissal as chairman but confirming Bespalov as president.

The idea was to keep Putilov as a figurehead to assure foreign investors that Rosneft would be a safe investment when it was privatized.

Perhaps predictably, one of Bespalov`s first acts was to dismiss Simonyan and a large number of other top managers, including the first president with responsibility for the Sakhalin-I project, Vladimir Nikishin.

A plan for the privatization of Rosneft was approved in late 1997 with many Russian and foreign companies expressing interest. By March 1998, it had been agreed that a stake of 75% would be sold to a single strategic investor with 67.63 million shares to be offered at a starting price of $2.132 billion, or $31.53 a share. The winner would also have to promise to invest at least $400 million.

The government thus valued Rosneft at $2.8 billion, despite a valuation of $2.3 billion by Dresdner Kleinwort Benson.

The price ignored the fact that Purneftegaz, the largest oil production subsidiary, had to repay loans to the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction, which with interest, amounted to $450 million while owing Federal and local taxes amounting to $166 million. For a company producing 8.3 million tons/year, this was a large debt.

There was a widespread feeling in Russia that the sale was being rushed through because the government was short of money and that the price was far too high. In any event, this feeling proved justified because the tender was a fiasco. None of the consortia, which had expressed an interest, put in a bid and another sale was planned for July 1998.

The new minimum price was $1.64 billion, and the requirement that the victor should pay off $120 million of Rosneft`s debts was dropped. It again appeared likely that no bids would be received and after a postponement to October, the sale was finally abandoned.

All this uncertainty has contributed towards a decline in output from 13.0 million tons in 1997 to 12.63 million tons in 1998, and a planned 12.2 million tons this year. Since Rosneft drilled 2,914,000 m in 1990 and only 199,800 m in 1998, it is surprising that the decline in oil production has not been faster.

Since Bespalov was dismissed and the government appointed Sergei Bogdanchikov as president, there are signs that the management of Rosneft is improving.

In this case, the foreign consortia involved in the Sakhalin offshore projects may justifiably conclude that Rosneft and Sakhalinmorneftegaz will be reliable partners in production-sharing projects that could yield huge returns for Russian and foreign companies.

The Author

David Cameron Wilson is editor of Eastern Bloc Energy, a monthly publication devoted to reviewing oil and energy issues in the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. He holds a PhD in Russian studies from Birmingham University, U.K.