Analysis suggests economic viability of trans-Caspian Sea gas line

The trans-Caspian natural gas pipeline is commercially viable and would bring positive returns to Turkmenistan under most scenarios analyzed by the Energy Institute at the University of Houston.

This conclusion holds even if Turkey is the sole buyer of Turkmen gas (Fig. 1).

Clearly, the project has risks, and some scenarios can make the project no longer viable or Turkmenistan may no longer receive positive returns. Turkmenistan's participation in the pipeline consortium may be required not only to share these risks with other partners but also to increase the country's returns via a stake in pipeline revenues, which appear to be larger than production revenues in most cases.

Delays in power-plant development have raised doubts about Turkey's ability to take all the gas agreed to from different suppliers. New legislation passed in August 1999, however, allows for international arbitration and limits the review of contracts by high courts. This improved environment should stimulate investment in new power plants.

Liberalization of the natural gas market is also being discussed, which may increase the natural gas demand in Turkey. A recent announcement by Iran to delay and cut the amount of its gas exports to Turkey creates an opportunity for other suppliers, including Turkmenistan.

At the same time, although our analysis indicates that the Trans-Caspian can survive along with Blue Stream and Iranian supplies, competitors, including Egypt and Iraq, are targeting the Turkish market as well. Therefore, there is pressure on Turkmenistan along with project companies and other supporters to expedite realization of the Trans-Caspian pipeline.

This analysis is also supported by the strategic benefits of the pipeline, which cannot always be represented monetarily but are equally important for countries in the region as well as for the US and EU. Both Turkish and Turkmen officials consider the trans-Caspian gas pipeline valuable in diversifying import sources (export routes) for Turkey (Turkmenistan) as well as strengthening relationships between Turkey and Turkmenistan.

To diversify successfully and obtain the best price, Turkey can definitely use all supply options available. The fact that there may be excess capacity in any of these pipelines at any time provides Turkey with the opportunity to negotiate the best price and forces exporters to compete with each other.

On the other hand, the pipeline provides Turkmenistan with a valuable bargaining tool against Russian state gas-transportation company Gazprom. Today, the country is in no position to negotiate with Russia for use of Gazprom's pipeline system because it has no other alternative (except for limited exports to Iran) to export its huge developed gas reserves.1

Also, once the Trans-Caspian pipeline is built and the cost for gas supply to Turkey is incurred, it should be economically attractive to supply gas to Europe. The economics can be even more attractive if gas can be swapped with Russia.

Natural gas and Turkmenistan

Natural gas will continue to be the fastest growing primary energy source in the world for the foreseeable future. At the same time, the competition among natural gas suppliers will continue to increase.

With 101 tcf of proved gas reserves (roughly 2% of total world reserves), Turkmenistan appears to be well positioned to benefit from increasing demand for natural gas. Compared with its competitors, however, Turkmenistan has certain disadvantages.

Since the country is landlocked, LNG is not a viable alternative, and the country is farther from hard-currency markets. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, natural gas resources in Turkmenistan have become too distant for major consumers, especially when Gazprom allows limited access to its pipeline system.

Ukraine, the largest consumer of Turkmen gas in the 1990s, has been unable to pay its bills. After cutting off supplies to Ukraine at the end of first quarter 1997, Turkmenistan resumed supply at the end of December 1998. Although only part of the payments were to be in cash, Turkmenistan had to cut supplies again in mid-1999 because of Ukraine's inability to pay.

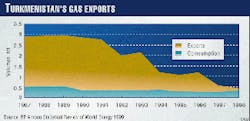

The result of these developments can be seen in Fig. 2: Turkmen gas production fell to 413 bcf in 1998 from almost 3 tcf/year in the late 1980s. Accordingly, exports fell to 77 bcf in 1998 from 2.4 tcf in 1987.

To revive Turkmen gas exports, alternative markets have been considered. Bridas and Unocal developed a potential pipeline route through Afghanistan, despite the civil unrest there, to serve the Pakistan market. And today, after the formal exit of Unocal, Bridas remains interested in this project.

Even if the Afghan problem can be somehow bypassed, Pakistan has no immediate need to import gas in the next 5 to 7 years. The country has been increasingly successful in finding and developing more of its own gas resources. Also, gas demand stagnates as a result of recent delays in power plant development.

In addition, the possibility of supplying gas to India through Pakistan seems even more remote as relations between these countries continue to deteriorate. The Chinese market was also considered.

The distance to be covered for Turkmen gas to reach potentially large markets in southeast China has made estimates for the cost of building this pipeline approach $10 billion. As a result of all these constraints, European markets, beginning with Turkey's, are currently targeted.

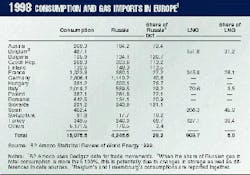

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects that gas consumption in Europe will increase to 27 tcf in 2020 from 15.1 tcf in 1998. This increase corresponds to annual growth of 2.9%.

Moreover, as gas reserves of the North Sea are depleted and countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region (including the Caucasus) continue to develop economically, prospects for Turkmen gas should improve. Table 1 shows demand potential in Europe.

The potential is significant for serious competition from the Middle Eastern countries with 100+ reserves-to-production ratios as well as from Algeria and Nigeria. Although most of these countries have similar transportation issues to address, some are rapidly developing their LNG export capacities (e.g., Algeria, Nigeria, and Qatar), while others such as Iran and Iraq are about to take advantage of their proximity to Turkey.

Russia remains the most immediate competitor for Turkish and European markets. Gazprom exports significant amounts of natural gas to Europe (Table 1) and is unlikely to provide additional capacity to Turkmen gas.

Under these circumstances, Turkmenistan would benefit greatly from an alternative pipeline. Two options have been talked about extensively: the trans-Caspian and Iranian pipelines.

The former, intended to bring Turkmen gas first to Turkey and then eventually to Europe under the Caspian Sea and via Azerbaijan and Georgia, has recently emerged as the more likely. Iran already expressed its support for the latter project.

In terms of total investment, the Iranian pipeline would probably be cheaper than the trans-Caspian pipeline and would also avoid the potential legal problems surrounding the status of the Caspian Sea.

But, the biggest drawback of the Iranian pipeline for Turkmenistan is the possible interruption or restriction of gas flow by Iran in the future. Russia, the largest natural gas reserves holder in the world, has been restraining Turkmenistan's gas exports for almost a decade. It is very likely that Iran, owner of the second largest gas reserves in the world, may follow a similar strategy in the future.

It is only a question of time before Iran will increase its ability to develop its own natural gas resources for export. It is this strategic reasoning, rather than US sanctions, which will make the Trans-Caspian line more attractive for Turkmenistan.

Also, the short-run commercial viability of the Iranian pipeline would solely depend on the Turkish gas market, while the trans-Caspian pipeline may benefit from gas sales in Azerbaijan and Georgia in addition to sales in Turkey.

Turkey

For some time, Turkey has been the largest potential neighboring market for Turkmen natural gas. Most projections of increased gas demand assume that Turkey would need a significant number of gas-fired power plants.

Electricity demand in Turkey has been rising at about 7-8% a year since the 1980s. The country started using build-operate-transfer and build-operate models extensively in the 1990s to allow private investment in the traditionally state-dominated power sector. However, legal problems delayed power plant developments until recently.2

As a result of these delays, even the state pipeline company, BOTAS, lowered its 2010 estimates of gas demand in Turkey from about 2.7 tcf to about 1.9 tcf (June 1998). Potentially, due to an economic slowdown of late 1998 and early 1999, some industry analysts are even more conservative than BOTAS, with estimates for Turkish gas demand in 2010 ranging from 1 to 1.4 tcf.

Nevertheless, gas consumption in Turkey has been increasing at more than 30% a year on average between 1987 and 1998. Given the rapid development of gas infrastructure in the early days, this may be misleading. But, between 1993 and 1998 consumption doubled, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of 15%, despite the problems in the power sector.

The new government of Turkey (formed May 28, 1999) was successful, however, in passing new legislation (Aug. 13, 1999) that allows for international arbitration in concession contracts and limits review, the high court responsible for reviewing concession contracts, to 2 months.3

Although electricity services are still considered as public service, future privatization of the sector is now easier to believe possible.

Overall, this improved legal environment should stimulate investment in power generation, which in turn will raise the demand for natural gas. If gas-fired power plant construction can average 2,000 Mw/year between 1999 and 2010 (as opposed to the official goal of 2,500-3,000 Mw/year), gas demand in Turkey will reach 2 tcf, assuming that 60% of gas imports will be used in power generation. This growth corresponds to an annual increase of 17%.

Industrial use of natural gas, especially for cogeneration, has also been increasing. Unaffected by legal debates of the 1990s, 1,224 Mw of cogeneration capacity was built in recent years. Another 1,485 Mw of capacity has signed contracts, and projects with a total capacity of 2,301 Mw are under review.

This trend should continue as BOTAS continues to expand its transmission and distribution grid in the industrialized western part of the country from Bursa toward Izmir. Even in places where pipelines are already laid, however, many industrial users burn LPG or naphtha in their cogeneration units because there is not enough gas.

As a result, industrialists without natural gas complain that they cannot compete long-term with companies that use cheaper natural gas. LPG sells at about $10/MMbtu; natural gas at about $4-5/MMbtu.

Turkey is also considering the liberalization of the natural gas sector. Although BOTAS resists the idea, it is generally understood that a more liberalized natural gas market would allow industrial users and independent power producers to import their own gas and local distribution networks to develop faster.

Unlike electricity, natural gas services have not been established as public service and hence it should be easier to open the natural gas market to competition. The recent successes of the new government in passing international arbitration legislation and other legislation in compliance with guidelines of the International Monetary Fund to liberalize the Turkish economy provide hope for commercialization of the natural gas market soon.

Residential and commercial markets are also promising. Currently, the main natural gas pipeline from Russia through the Balkans passes through the Marmara region (northwest Turkey), the most populous and the most industrialized in Turkey, before reaching Ankara in the Central Anatolian region.

About 16-17 million people live in the region (about 10 million live in Istanbul alone), most with no access to natural gas. The region has four seasons with hot and humid summers, especially in July and August, and cold and wet winters.

The heating season usually lasts from early October until late April; but it is not unusual to experience single digits (Celsius) even in September and May.

Although the population of the region represents 26% of the total population, about 40% of disposable income in Turkey is generated in the Marmara. Per-capita gross domestic product and consumption of electricity are significantly larger than the averages for Turkey.

For example, in Kocaeli, per-capita GDP is 2.5 times the Turkey average, which is about $6,000 based on purchasing power parity, and per-capita consumption of electricity is 2.6 times the national average, which is about 1,300 kw-hr (1997 numbers, State Institute of Statistics and TEDAS).

Residential users with access to natural gas pay about $6/MMbtu.

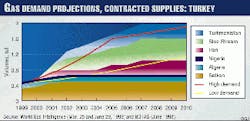

Fig. 3 provides a range between a low-demand case and BOTAS' June 1998 estimates (the high-demand case) superimposed on total import potential for which there is some form of contractual agreement between Turkey and the exporting country.

The chart clearly indicates that the trans-Caspian pipeline will not be needed until 2003-04 even under the high-demand case if both the Blue Stream and Iranian pipelines are built and can deliver contracted quantities in time and if the Balkan pipeline's capacity can be increased in time.

Iran already delayed and decreased the amount of its gas shipments to Turkey.4 Fig. 2 represents these new amounts. The Blue Stream pipeline will be the deepest subsea pipeline.

Additionally, the bottom of the Black Sea is uneven and the water very corrosive at those depths.5 Weather conditions can also be very difficult, especially during the winter.

Therefore, it is very likely that there will be delays during construction and potential delays in supply during operation. More importantly, financing for the project is not fully secured yet.

Meanwhile, BOTAS has not made significant progress in developing the Samsun-Ankara connection that would bring Blue Stream gas to the market. Nevertheless, Fig. 3 represents the full amounts published in World Gas Intelligence (Mar. 25, 1999).

Regardless of these supply alternatives, a purchase agreement was signed between Turkey and Turkmenistan in late May 1999 for 177 bcf starting in 2002 and rising to 565 bcf by 2005. Figs. 3 and 4 lower these estimates and assume that gas imports from Turkmenistan reach 353 bcf in 2006 and remain constant until 2011 when they reach 530 bcf.

Georgia

Although there is sufficient infrastructure for gas delivery in Georgia, significant investment is required to rehabilitate it.

In 1992, Georgia imported 173 bcf of gas from Turkmenistan via the Russian pipeline system. In 1998, Georgia consumed about 53 bcf of gas-imported from Russia. If residential and commercial consumers can get access to gas, then Georgian gas demand will readily exceed 100 bcf/year.

Those residential consumers who have access to gas are paying about $4.25/MMbtu, whereas others are using electricity or LPG for their cooking and heating requirement. LPG is very expensive, with consumers having to pay as much as $14/MMbtu.

The electricity market is privatized in Georgia and consumers have been paying their bills. When gas becomes available, consumers may happily switch from LPG to gas and should be able to pay for it.

Georgia is in the process of privatizing local gas-distribution companies with some smaller companies already privatized. For these reasons, the usual apprehension about the ability of customers in transition economies to pay for energy services does not seem to apply for Georgia.

Georgia also needs roughly 36 bcf/year for its power plants. World Bank officials acknowledge the potential of the Georgian gas market.4

Fig. 4 assumes Georgian demand for Turkmen gas would steadily increase from about 100 bcf in 2002 to 353 bcf in 2026 from both factors-switching from LPG to gas for domestic fuel and gas-fired electric power production.

Basically, Georgia during 2002-2010 will return to consumption levels of the early 1990s.

Since 1996, Georgia has had one of the fastest growing economies around the world, with GDP growth at more than 10% for 1996 and at 11.3% in 1997. GDP continued to grow significantly in 1998 at about 7%, despite the global economic crisis. The 1998 GDP is estimated around $4.8 billion.

In terms of purchasing-power parity, this corresponds to a per-capita GDP of $1,400. As in Turkey, however, per-capita income is probably significantly higher in industrialized parts of the country and in such major cities as Tblisi.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan resembles Georgia in its well-developed gas infrastructure.

Because of a limited supply of gas, consumption is considerably less than potential demand. Azerbaijan consumed 560 bcf in 1990, compared with 184 bcf in 1998.

Unlike Georgia, however, Azerbaijan has been subsidizing residential gas consumers considerably (gas to these consumers being nearly a "free good") while charging the industrial consumers more or less market prices. In recent years, attempts have been made to charge higher prices to residential consumers.

Azerbaijan aims to increase domestic consumption of gas. Although the country is expected to develop its own resources and be self-sufficient by 2010, Azerbaijan may turn to one of its old suppliers, Turkmenistan, in the interim.

Azerbaijan's ability to become self-sufficient, however, depends upon how rapidly the country will be able to develop its recently discovered Shakh Deniz field which may contain as much as 11.3-19.8 tcf of gas.

Fig. 4 assumes that Azerbaijan consumes an average of 172 bcf/year of Turkmen gas between 2002 and 2009, starting at 177 bcf in 2002 and peaking at 247 bcf in 2005. After 2010, Azeri gas will substitute for Turkmen gas.

But this substitution can happen even earlier. If Shakh Deniz field economics turn out to be very attractive and gas can be produced at competitive prices with respect to Turkmen gas, then Azerbaijan may become a tough competitor to Turkmenistan.

The Azeri economy is not performing as well as that of Georgia. In 1997, GDP was estimated at $4 billion, which translates into about $500 per-capita GDP in terms of purchasing-power parity. Nevertheless, the economy grew at 1% in 1996 and at 6% in 1997.

Also, Azerbaijan continues to attract significant investment in its oil and gas sector. The Trans-Caspian pipeline will likely stimulate gas infrastructure development and rehabilitation in Azerbaijan as well.

Consumers' ability to pay, however, remains an open question.

NPV analysis

Fig. 2 makes clear that Turkmenistan has the potential to export more than 2 tcf/year of natural gas if the country had an alternative pipeline and paying customers along the way of that pipeline. Our goal is to evaluate whether the 2,000-km (1,250-mile) Trans-Caspian pipeline can be that alternative.

Accordingly, we developed a model in which demand profiles for Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey represented in Fig. 4 are used.6 These profiles are then altered in certain scenarios to analyze the impact of lowered or delayed gas sales on the commercial viability of the project.

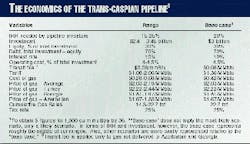

Table 2 summarizes other key variables of the model, the range of their possible values, and the values used for the base case.

With the assumptions of the base case, the model yields the following results. The net present value (NPV) of total gas revenues over 30 years of operations is $10.4 billion. The NPV of pipeline (tariff) revenues is $1.8 billion; the NPV of transit fees (earned by transit countries, Azerbaijan and Georgia), about $608 million. The NPV of sales to Turkmenistan is $1.3 billion.

In short, for all stakeholders involved with the project, there will be positive returns.

As noted earlier, the base case is only a likely scenario, not necessarily the most likely. As earlier discussion indicates, there are significant risks associated with this project, including fluctuations in the cost of the pipeline, demand forecasts, and other geopolitical complications of the region.

To address these issues, we analyzed seven different scenarios. Table 3 summarizes assumptions of each scenario that are different from the base case reported in Column 3 of Table 2. All other assumptions are the same as in the base case.

By design, pipeline investors are assured a minimum return. We account for this by adjusting the tariff rates. In Column 3 of Table 3, we report these tariff rates.

The first two scenarios represent potential changes in pipeline investors' perception of the project risk. An improvement in this perception is shown as a 5% decline in the required internal rate of return (IRR; Scenario A), and a perception of higher risk is presented as an increase of 5% in the required IRR (Scenario B).

The next two scenarios are run to cover the range of estimates found in the industry press for the cost of building the Trans-Caspian pipeline.7

Scenario E explores the impact of higher gas sale prices on the project even if the pipeline costs are high. In scenario F, we assume that Azerbaijan does not purchase any gas from this pipeline.

Given the significant decline in returns to Turkmenistan under Scenario F, we do not represent another scenario in which sales to Georgia are eliminated, as the latter would obviously yield negative returns to Turkmenistan. Instead, we offer Scenario G in which the only buyer of Turkmen gas is Turkey, but the pipeline costs are low and Turkey pays a higher price.

Fig. 5 compares the key results for each of these scenarios with those of the base case: cashflows to three main stakeholders, Turkmenistan (producer),8 pipeline investors-operators (tariff revenues), and transit countries.

Fig. 5 makes clear that Turkmenistan's returns (production cash flow) are most sensitive to changes in certain crucial variables. On the other hand, transit countries and pipeline operators are guaranteed significant returns.

The NPV of transit countries' revenues ranges from $480 million (Scenario G) to $608 million in all other scenarios. The NPV of pipeline cash flows ranges from $960 million (Scenario A) to about $2.6 billion (Scenario B).

In contrast, the NPV of production cash flows to Turkmenistan is $129 million in Scenario F (no sales to Azerbaijan) and $80 million under Scenario G. This last scenario is important in that it yields positive NPV for Turkmenistan even when Turkey is the only buyer, albeit under low-investment and high-price assumptions.9

These results yield a number of inferences.

- Transit countries, Azerbaijan and Georgia, are clearly winners. In addition to collecting transit fees, they will have a more diversified portfolio of gas suppliers. This will certainly lower the cost of gas in these countries.

For Azerbaijan, this pipeline will also provide a potential alternative to export gas in the future when the country develops its own gas resources.10

- In the long value chain of gas supplies from exploration and production to transportation to distribution, it is those involved in exploration and production who take the maximum risk and should get the maximum return, followed by those involved in transporting gas, and finally by distribution companies.

In the case of the trans-Caspian pipeline, however, transmission and distribution companies receive higher returns. Today in Georgia, gas to the residential consumers is sold at about $4.25/MMbtu, which is considerably higher than the gas supply cost of $1.7-2.0/MMbtu. This indicates an attractive margin to the distribution companies.

Also, in Turkey the price of natural gas in electricity generation has been around $4.5/MMbtu ($6/MMbtu for residential users), which leaves BOTAS or municipally owned LDCs with a decent margin even if BOTAS pays the high end of our price range, $2.44/MMbtu (unless tariff is larger than $2/MMbtu).11

As shown in Fig. 5, in all scenarios except two (Scenarios A and C), pipeline investors get higher cash flows than do the producers. This situation can be defended because pipeline investors are taking the bigger risk.

Even after getting take-or-pay contracts from all three consuming countries, the pipeline company is still exposed to the possibility of being unable to sell gas at the forecast level which will affect the cash flows.

It may be impossible to eliminate political risks completely or to depend on political risk insurance for recovery. If Turkmenistan participates in the pipeline consortium, these risks can become more tolerable for other partners, and Turkmenistan, in return, may benefit from the pipeline revenues to support its production cash flow.

The "Production + Pipeline" column in Fig. 5 shows the more stable nature of these returns when combined.

References and notes

- The application of financial and economic option valuation methods to the analysis of natural gas pipelines indicates that uncommitted capacity in a pipeline is a valuable asset and possesses the payoff attributes of a call option. For details, see "An Option Valuation Model for Options on Capacity in Integrated Landbased and 'Seaborne' Trunklines for Natural Gas and LNG" by Gregory Pickett in Conference Proceedings of 20th Annual North American Conference of USAEE/IAEE.

- See Power Marketization in Turkey (May 1998), an Energy Institute White Paper by S. Gürcan Gülen.

- The Caspian Sea poses its own challenges. The consensus among analysts, however, is that construction of the undersea portion of Blue Stream will be more challenging than construction of the subsea portion of the Trans-Caspian pipeline. Further analysis of both projects may change this consensus.

- World Gas Intelligence, Aug. 12, 1999, p. 6. Note that we assess the commercial viability of the pipeline independent of the timing of its construction. Although in Figs. 3 and 4, we assume that the pipeline will start delivering gas in 2002, this may be delayed, as our discussion on the potential of Turkish gas market and other supply alternatives indicates. This delay will not affect the results of our analysis, however.

- Recently, the option of expanding capacity of Baku-Supsa oil pipeline as the first leg of Baku-Ceyhan pipeline has gained prominence. Building the trans-Caspian gas pipeline along the oil pipeline will decrease costs, at least based on rights of way agreements. In that case, the cost of building the pipeline will more likely be near the low end of our estimates.

- Currently, almost 95% of natural gas is produced by the state company Turkmengas.

- Note that under this scenario, cost to Turkey including tariff and transit fees is about $4.52/MMbtu, which is about 8% higher than the current BOTAS price.

- There is already talk about this potential since BP Amoco's discovery of large gas resources in Shakh Deniz.

- In power generation, the price of natural gas in Turkey is about equal to the price of fuel oil and more than twice the price of lignite in net calorific basis (IEA/OECD Energy Prices and Taxes). Coal-fired plants, however, cost almost twice as much, take longer to build, and are less efficient. In addition to these factors, increasing environmental awareness, have been pushing Turkey toward gas-fired generation. Attractive margins should therefore remain.

The Authors

Bhamy V. Shenoy is a manager at Hagler Bailly Services for US Agency for International Development sponsored projects undertaken by Hagler Bailly. He is deputy project manager for Republic of Georgia oil and gas sector reform and task leader, Central Asian Republics: Regional Energy Sector Initiative.

Shenoy has held various positions at Conoco during his 21-year career. He holds a BTech in mechanical engineering, Indian Institute of Technology-Madras; MS in industrial engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology-Chicago; PhD in business administration, University of Houston; and attended the Executive Program in Business Administration at Columbia University, New York City.

S. Gürcan Gülen is a research associate in the Energy Institute at University of Houston's College of Business Administration. Gülen holds a PhD in economics from Boston College and a BA in economics from Bosphorus University, Istanbul.

Michelle Michot Foss is director of the Energy Institute and assistant research professor at the University of Houston's College of Business Administration. Michot Foss has a BS in biology (geology minor) from the University of Southwestern Louisiana, Lafayette, MS in mineral economics from Colorado School of Mines, and PhD in political science from University of Houston.