NIS Gazprom Neft studies low-salinity waterflooding in Serbia

Slavko Nesic

NIS Gazprom Neft

Novi Sad, Serbia

Vladimir Mitrovic

University of Belgrade

Belgrade

NIS Gazprom Neft’s Scientific and Technology Center studied improved oil recovery in Serbia’s K field using low-salinity waterflooding (LSW). It was Serbia’s first LSW project amid industry’s ongoing research worldwide into LSW to improve oil recovery.

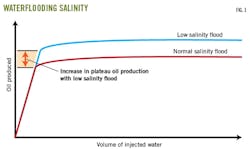

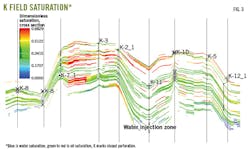

Fig. 1 shows other researchers’ comparison of low-salinity water and normal-salinity water in core flooding. Injection-water chemistry continues to evolve.

Different pore-scale tests have confirmed LSW’s benefits over normal salinity waterflooding (NSW).1-2 LSW alters wettability properties and induced fine-particles migration. Low-saline water contacting clay minerals destabilizes clays and mobilizes fine particles through porous media.

Mobilized fine particles clog small pores and reduce permeability. But this is counterbalanced by injected water’s tendency to find alternate paths through a formation, increasing displacement efficiency.

Lack of mobility control and fine particles migration can lower permeability, reducing injectivity and hindering the effectiveness of waterflooding.3-4

Industry continues to study interaction between a formation and low-saline water, which has a different contact angle than normal water. Wettability alternation changes residual oil saturation and increases oil recovery.

The Serbian study findings could be applied to similar issues observed in other fields in the Pannonian basin. Industry has studied LSW in many areas, including western Iran’s Cheshme Khosh field, Russia’s Bashtrykskoye and Zichebashskoe fields, India’s Upper Assam basin, and the North Sea’s Snorre field.

LSW worked on some Serbian study wells, but other wells experienced reduced injectivity. NIS Gazprom Neft plans to add an injection well during 2019 to improve LSW’s effectiveness in K field. More Serbian fields are being considered as candidates for LSW projects.

Field study

NIS Gazprom Neft discovered K field in 2012, drilling two slim-hole exploration wells to 1,000 m in Lower Miocene sediments. The field came on stream in 2015.

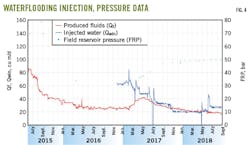

Waterflooding started in October 2016 because of marginal production and production decline. Production began to increase in February 2017. Reservoir pressure increased about 2 bars/month after 3 months of waterflooding.

In 2018, 8 wells were in production, one well was used for water production (K-4), and one for pressure monitoring (K-1).

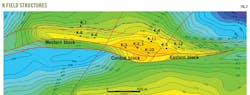

Fig. 2 shows three K-field blocks (Central, Eastern, and Western), separated by faults. Reservoir rocks are complex conglomerates consisting of sandstone, clays, quartz, calcite, and alevrolites with 10% carbonate content.

Reservoir porosity varies from 18.1-32.2% and permeability from 70-500 md depending on the well. Fig. 3 shows K field’s saturation profile.

Well K-1 was in production during 2015-16. Its initial natural flow was 7-12 cu m/d but declining so a sucker rod pump was installed after 2 months.

Following an electric submersible pump (ESP) workover, the well produced 2-3 cu m/d in February 2016. In November 2016, the well was completed for pressure monitoring.

Well K-2 has produced since 2015. After 5 months of natural flow of around 15 cu m/d, crews installed an ESP because production was declining.

Waterflooding started in November 2016 with effects first observed in K-2 since it is closest to the injection well. Oil production increased to 12 cu m/d in May 2018 from 8 cu m/d in February 2018.

Well K-3 started production from 2015 with an ESP installed from the beginning. Oil production gradually declined to 6 cu m/d in November 2016 from 23 cu m/d in 2015. With waterflooding, oil production increased to 8 cu m/d in May 2018 from 6 cu m/d in February 2018.

Well K-5 started production from 2015 with an ESP installed after 2 months of natural flow. Oil production gradually declined to 2 cu m/d in November 2016 from an initial 10 cu m/d. After waterflooding, oil production increased to 5 cu m/day in May 2018 from 2 cu m/d in March 2018.

Well K-6, which had an ESP installed from the start of coming on stream in 2016, initially produced 20 cu m/d but declined to 3 cu m/d. Waterflooding did not change production.

Well K-7, equipped with an ESP, came on stream in 2016. It initially produced 8.5 cu m/d followed by decline to 3 cu m/d. This well is in another block. Waterflooding did not improve production.

Well K-8 produced from 2016-18 with an installed ESP from the beginning. Initial production was 4 cu m/d followed by constant decline until May 2018 when crews shut in the well. This well is in another block and its production was unaffected by waterflooding.

Well K-11 was in production from 2015-16 with a progressing cavity pump from the beginning. Oil production rate was around 3 cu m/d. Crews completed the well for water injection in October 2016.

Well K-12 came on stream with an installed ESP in 2015. Oil production rate was around 2 cu m/d. After waterflooding, production stabilized and increased to 3 cu m/d.

Researchers observed a pressure decline to 35 bars in November 2015 compared with 75 bars after the field came on stream 500 days earlier. The field’s fluid rate fell to 25 cu m/d in October 2016 from an initial 85 cu m/d.

After lab analysis and reservoir modeling, researchers tried waterflooding to support pressure and improve oil recovery. They selected the Central block, which is 30 m and had the most remaining reserves of the three blocks.

Water availability

Water availability for flooding initially was a problem because produced water volumes were insufficient for positive compensation between volumes of injected water and oil production, which was around 25 cu m/d.

Additional water was needed because injection water volume must be higher than produced fluids volume for pressure support and oil displacement.

In May 2016, crews isolated oil intervals at well K-4 and two shallow water layers were perforated (785-800 m and 730-740 m). Researchers analyzed water samples from these shallow water layers.

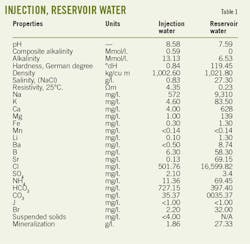

The table shows shallow water properties, which were found to be compatible with reservoir water. Well K-4 was tested for water production and connected via pipeline with injection well K-11. The injection water has a lower calcium level than reservoir water.

When clays are present in water-injection zones, clay swelling can impair injectivity and increase reservoir pressure. Analysis of reservoir rock samples in injection well K-11 showed no clays.

Suspended solids content was lower than 4 mg/l., satisfying criteria for waterflooding. Well K-11 was completed as an injection well. Waterflooding started in November 2015 with a maximum fluid rate from March 2017 to June 2017 of around 40 cu m/d.

Injectivity declines

The biggest waterflooding issue was injectivity decline, stemming from:

• K-1 having lower reservoir properties compared with other zones.

• Ineffective acid stimulation due to rock complexity.

• Clay migration during LSW.

Crews performed three acid stimulations to restore injectivity but without improving water-injection rates. In February 2017, water injected into well K-11 decreased to 18 cu m/d from 55 cu m/d.

Acid stimulation involved a mix of hydrofluoric acid and hydrochloric acid. After the acid treatment, water injectivity increased to 70 cu m/d. But during March 2017, injection water rates continued to decrease, stabilizing at 47 cu m/d April-June 2017.

In June 2017, crews applied a second acid treatment because the water injection rate started to decline. But the injection water rate still decreased until reaching 20 cu m/d in November 2017. A third acid treatment in May 2018 failed to restore earlier injectivity.

In June 2018 after a pump workover, the injection pressure increased with a higher pump frequency. The water injection rate climbed to 5 cu m/d. However, this volume of injected water was insufficient for waterflooding and oil displacement.

Fig. 4 shows the production profile with injection and pressure data during waterflooding.

Water injection into the bottom zone of the reservoir caused better sweep efficiency and oil displacement. Displaced oil flowed upward of the reservoir into the injection zone. Oil recovery increased during bottom-up waterflooding. Gravity decreased the injection-water velocity.

Well K-11’s oil production started to increase after 4 months of water injection. The highest fluid production was 40 cu m/d, measured April-June 2017. That compared with 20 cu m/day before waterflooding.

Researchers were unable to restore well K-11’s water injectivity sufficiently despite acid treatments. They are working to develop strategies to handle formation impairment during water injection, such as improved water treatment, acid stimulation of wells, and more injection wells.

References

1. Nasralla, R., Alotaibi, M., and Nasr-El-Din, H., “Efficiency of Oil Recovery by Low Salinity Water Flooding in Sandstone Reservoirs,” Society of Petroleum Engineering Western North American Region Meeting, Anchorage, May 7-11, 2011.

2. Ahmetgareev, V., Zeinijahromi, A., Badalyan, A., Khisamov, R., and Bedrikovetsky, P., “Analysis of Low Salinity Waterflooding in Bastrykskoye field,” Journal of Petroleum Science and Technology, Vol. 33, No. 5, Mar. 16, 2015, pp. 561-570.

3. Tang, G., and Morrow, N., “Salinity, Temperature, Oil Composition, and Oil Recovery by Waterflooding,” SPE Reservoir Engineering, Vol. 12, No. 4, November 1997, pp. 269-276.

4. Borazjani, S., Chequer, L., Russell, T., and Bedrikovetsky, P., “Injectivity Decline During Waterflooding and PWRI due to Fines Migration,” SPE International Conference and Exhibition on Formation Damage Control, Lafayetta, La., Feb. 7-9, 2018.

Authors

Slavko Nesic ([email protected]) is a reservoir engineer in the scientific technology center of NIS Gazprom Neft. He worked on several enhanced oil recovery (EOR) projects in Serbia, including CO2 sequestration and storage. He holds BSc (2012) and MSc (2013) degrees in petroleum engineering from the University of Belgrade Faculty of Mining and Geology where he is completing his PhD studies. He participated in several research internships at the Institute of Arctic Petroleum Technologies at Gubkin University (Moscow) and has experience in reservoir engineering, reservoir management, and reservoir modelling.

Vladimir Mitrovic ([email protected]) is a petroleum engineering professor at the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Mining and Geology. He has 40 years of experience in reservoir engineering research and teaching. He received BS (1976), MS (1986), and PhD (1991) degrees in petroleum engineering, all from the University of Belgrade. He collaborates with oil companies and governments on reservoir engineering, field development, and environmental analysis. He supervised reservoir engineering and oil development projects in Serbia for more than 30 years.