Regulatory actions loom for US pipelines in 2001

For US oil and gas pipeline companies, events of 1999 and 2000 make for sober prospects for 2001.

The US Congress late last year failed to reauthorize major pipeline safety legislation. Exactly what actions the next Congress will take and under what pressures from a new administration, a new Congress, and an alarmed public are open questions.

Over the US pipeline industry hang the specters of two major, fatality-involving pipeline accidents in the past 18 months. These have heightened regulatory and legislative attention-and both are driven by growing public alarm.

Events

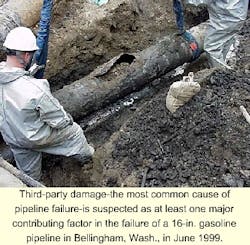

On June 10, 1999, at about 3:30 p.m. local time, a 16-in. pipeline owned and operated by Olympic Pipe Line Co. ruptured, leaking gasoline into creeks within the city of Bellingham, Wash.

When, slightly more than 90 minutes later, the gasoline ignited, engulfing an area about 1.5 miles downstream of the location, two 10-year-old boys and an 18-year-old man died. US National Transportation Safety Board said eight additional injuries were documented, along with significant property damage to a single-family residence and Bellingham's water-treatment plant.

Nearly 6 million bbl of product also caused extensive environmental damage to the affected waterways.

Although NTSB's investigation has yet to issue a final report, preliminary remarks before Congress in spring 2000 by the board's Robert Chipkevich pointed to a web of interconnected problems: damage from previous excavation, inadequate pipeline integrity monitoring, and poor personnel training.

(NTSB is an independent federal agency charged by Congress with investigating major US transportation accidents, including pipeline ones, and issuing safety recommendations aimed at preventing recurrences.)

The other major pipeline accident was far more severe in loss of life.

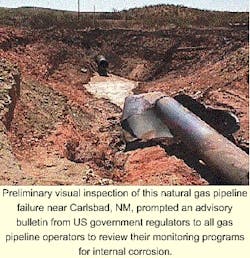

On Saturday, Aug. 19, 2000, at about 5:30 a.m. local time, one of three natural gas pipelines in a right-of-way in Eddy County, NM, ruptured about 30 miles north of Carlsbad. Among the three families camping along the nearby Pecos River, 12 people were killed, including 5 children. The explosion ripped an 86-ft long crater.

The line is owned and operated by El Paso Natural Gas Co., a wholly owned subsidiary of El Paso Energy Corp., Houston. The pipelines supply consumers and electric utilities in Arizona and Southern California.

Again, NTSB's investigation is ongoing, with no report expected for more than a year. But some hint of at least part of the possible causes came from an advisory bulletin issued 6 days later by the US Department of Transportation's Research and Special Programs Administration.

The bulletin addressed "owners and operators of natural gas transmission pipeline systems" to review their "internal corrosion monitoring programs and operations."

And it said: "Operators should give special attention to pipeline alignment features that may contribute to internal corrosion by allowing condensates to settle out of the gas stream."

RSPA's Office of Pipeline Safety, in a preliminary investigation, had found "wall thinning on damaged pipe...consistent with that caused by internal corrosion."

The ruptured section was removed by NTSB and taken to its metallurgy lab for examination. As recently as September 2000, however, RSPA was saying, "it is too early to say what caused the pipe to rupture."

Congressional failure

The Bellingham incident lent an air of urgency when the US Senate in second quarter 2000 took up reauthorization of the Natural Gas Pipeline Safety and Hazardous Liquid Pipeline Safety acts. Both were due to expire on Sept. 30, 2000.

Testimony before the US Senate commerce committee brought to the surface some regulators' frustrations in trying to get RSPA and OPS to act more aggressively and quickly on several fronts involving pipeline safety.

Among other complaints, NTSB's John Hammerschmidt said RSPA's incident-reporting forms are poorly designed and fail to obtain data needed for analysis (OGJ Online, May 11, 2000).

DOT's Kenneth Mead said "Critical safeguards required by Congress for hazardous liquid and natural gas pipelines are at least 5 years overdue" from RSPA.

RSPA Administrator Kelley Coyner reminded the Senate panel, however, that in 1999 the agency had issued an operator-qualification rule that requires companies to develop and maintain a written qualification program to assess the ability of each worker.

But, said Mead, RSPA had failed to establish training requirements for the operators.

While these hearings were proceeding and as the full Senate neared consideration of the reauthorization, RSPA announced it wanted to fine Olympic Pipe Line the largest-ever proposed fine against a pipeline operator for safety violations: $3.5 million.

Then in July came the Carlsbad explosion.

By the time the Senate again took up consideration of pipeline safety act reauthorization, the surrounding political and regulatory air was even more charged.

As a result, in early September, the bill the Senate passed and sent for US House of Representatives consideration carried more onerous provisions. Among them, the legislation would have imposed a $100,000/day maximum civil penalty for pipeline safety violations-quadrupling the previous maximum.

But statements by major industry associations indicated a willingness to accept even a bill with tougher provisions, so long as industry had a bill, something to guide it into the next couple of years, something on which to base decisions about maintenance, inspection, and training.

Time was running short, however. At the end of the month, with no compromise bill in hand, two key House members nonetheless called for an even tougher pipeline safety bill.

Legislation is expected to require pipeline operators to adopt integrity management programs, regardless of whether DOT completes a pending rulemaking to require them (OGJ Online, Sept. 28, 2000).

And the legislation is likely to require more-frequent pipeline inspections in high-population or environmentally sensitive areas.

By mid-October, however, no bill had been passed and Congress adjourned to attend to election matters, leaving the matter to a new Congress.

New rules

But regulators were not waiting.

In a sign of what may be in store for operators in 2001, DOT announced in early November 2000 new, stronger safety and environmental standards for pipelines moving hazardous liquids through populated areas, unusually sensitive environmental areas, and waterways used to transport vital goods an supplies.

The new rules include mandatory testing, which most operators already conduct voluntarily, but at double the current industry practice rate. Moreover, it requires operators to make available for government review their plans for assessing and addressing risks that can lead to failures.

Starting this year, DOT and its state-agency partners will review operator integrity-management programs. They will address such risks as corrosion, outside force, human errors, and material defects.

Also included will be an operator's identification of pipelines that could affect high-consequence areas, selection of assessment methods and schedules, and evaluation of risk factors unique to a system.

Effective date for the new rule is Mar. 31, 2001. DOT said an operator must complete an identification of all pipeline segments that could affect a high-consequence area by Dec. 31, 2001. An operator must develop a written integrity-management program by Mar. 31, 2002.

According to DOT, the rule affects nearly 87% of federally regulated hazardous liquid pipelines and is the first of a series of rules DOT will issue addressing pipeline integrity.

Similar rules will be developed for all pipelines under federal or state oversight, said the agency, including pipelines moving natural gas.

Figures and the future

And more regulation and closer scrutiny seem likely for pipeline operators in 2001 and beyond. The preliminary results of both the Bellingham and the Carlsbad incidents point operators to where they must concentrate.

DOT pipeline incident figures for oil and natural gas pipelines in the 1990s do not show an infrastructure that is deteriorating from age or lack of attention.

But those same figures do not show a system whose safety record is improving steadily enough for public acceptance of the risks of pipelines running through population centers.

Whatever form federal pipeline safety reauthorization takes under a new Congress, the increasingly acrimonious tenor of last year's debate, the clear direction toward closer regulatory scrutiny, and an atmosphere haunted by the ghosts of 15 victims of pipeline catastrophes make for a sober outlook for US pipeline operators in 2001.