New markets, business models key to future Russian oil production increases

This is the second of a two-part series updating the status of Russia's oil sector.

The ability to expand domestic and foreign markets, not limited access to working capital, will determine oil production in the Russian Federation within the next 5 years.

This is the view of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, CEO of OAO Yukos, Moscow, as presented at the Cambridge Energy Research Associates' annual executive conference in Houston Feb. 13 and in a subsequent interview with OGJ.

Khodorkovsky also believes that, if Western companies come to understand the economic conditions that are now reshaping Russia's petroleum industry, they may yet find profitable ways in which to operate in Russia.

"Some of those who have attempted to operate in Russia have been unsuccessful. This is not a satisfactory thing for us to realize because it makes the international community think that Russia is not a very attractive object for investment," he said.

Market limitations

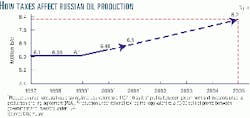

"If you take a look at a map of Russia, you will see that the opportunities to export oil are limited," he explained (Fig. 1).

On the domestic front, Russian consumption may rise to 2.8 million b/d from 2.3 million b/d by 2005. Internationally, however, Russian exports to Europe may increase to 5 million b/d from 3.7 million b/d today.

Yet, in other areas, such as exports to Japan from Sakhalin Island and exports to China from Siberia and the Russian Far East hold limited mid-term growth potential, as harsh working conditions and limited infrastructure development pose technical and political barriers that may take years to overcome.

"Thus, the opportunity for growth in the Russian oil industry in the next 5 years is limited," Khodorkovsky said. "We have no deepwater ports, so we cannot ship our oil to the US, for example. Therefore, the maximum oil production in Russia [will be] 8.2-9.0 million b/d."

Misinterpretation

Khodorkovsky believes that Western investors and analysts wrongly interpret the current situation and the ability of Russian oil companies to react to changing economic conditions.

"Five years ago, money was the most important thing for us," he told OGJ. "The industry was extremely inefficient; cash flow held us by the throat; and there was nothing else that we thought about."

Yet, after 5 years of progress, reorganization at the corporate level, improved technology management at the field level, and increased commodity prices have resolved the cash flow problem.

"Today, we understand the most important thing is knowledge and are looking to acquire this knowledge at the best price." Working towards this goal, Yukos is trying three business models: "true cooperation" with oil companies, service company alliances, and work-for-hire arrangements.

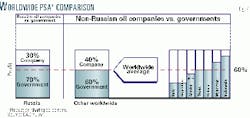

"There is a myth that foreign companies operate at a lower cost than Russian companies under comparable geological and environmental conditions," Khodor- kovsky said. "As a matter of fact, the cost of production incurred by Western companies under similar conditions-for instance in Western Canada, Kazakhstan, and Alaska-are higher than the costs of Russian oil companies (Fig. 2)."

There are several reasons for this. First, Russia has a 110-year-old oil industry, with experience exceeded only by the US. "This means that Russia has the manpower with necessary qualifications. It has an elaborate system of education and training in place."

Second, the Russian petroleum industry manufactures most of its equipment at a much lower cost than in the West. "Only a small portion of the ever-growing investments by Russian oil companies is made in imported equipment," Khodorkovsky said. At Yukos, for example, only 4% of the company's expenditures are for foreign equipment. All the rest is bought domestically at domestic prices.

Furthermore, and just as important, due to the global economy, Yukos and other Russian companies have the same access to the best Western field services in addition to their own. "This explains why our expenditures under similar conditions are lower than our Western counterparts," he said.

Taxes vs. production

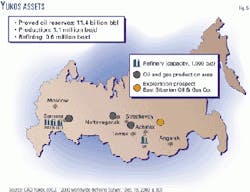

Misconceptions of the current Russian tax regime and the "so-called advantages" of production-sharing agreements (PSA) is another sticking point with Khodorkovsky. "Until 1999, there was an unsustainable, very tough tax regime in effect. If this is translated into PSA terms, the government took 100% of the profit with '-10%' of the profit remaining with the investor."

Since 1999, however, legislative action by the Duma and executive branch has altered the situation (Fig. 3). "Now the government takes about 70% of the profits, which represents a conversion into PSA terms, and about 30% remains in the pockets of the oil companies," Khodor- kovsky said. In 2000, Russian production broke a 5-year flat streak with output rising to 6.5 million bo/d, a 5.7% increase over 1999 (OGJ, Feb. 19, 2001, p. 30).

"As anyone can plainly see, as the effective tax rate fell, the Russian industry grew. Now maybe even the government finally believes this."

Two concerns, however, have yet to be resolved. Concerning the profits tax, ongoing negotiations appear to be showing great promise. "The outlines look perfectly acceptable. It's very similar to what you see in world practice," he said.

Of even greater concern is the export duty. "The government wants to leave this as is but retain the rights to amend it as necessary," he said. "Yet the prevailing opinion is that the customs duty really ought to be regulated by a law rather than administrative fiat." This question will perhaps be solved this year.

Equal conditions

Concerning PSAs, Khodorkovsky is not so sure this investment vehicle will provide the advantages foreign investors so desperately seek. "We can see that the production-sharing format being offered by the Russian government is less advantageous than the international PSA standards," he said (Fig. 4). Khodorkovsky says that if Western companies really desire PSAs, however, they can work towards this goal.

"But they should not for a moment expect that this will be a more favorable regime than the national tax regime," he said. Furthermore, he feels that PSAs, or "custom-designed" joint venture agreements, for that matter, may continue to create a condition of animosity between the Russian government and the oil industry.

"There is one thing that we are not going to tolerate, ever, and that's for Western companies to have more preferential terms in Russia than we do. Equal conditions, fine; preferential, no," he emphasized.

Instead, Khodorkovsky believes that there should be one all-embracing system, founded on an unbiased national tax regime, which is perhaps the only practical way to produce a competitively fair working environment.

"Looking back, if Conoco [had] agreed to work within the national tax regime instead of seeking preferential treatment, they may have been in far better shape today," he said. Since Polar Lights production came on line, for example, the company has suffered four major tax increases.

In addition, external forces may also have played a role in this tax volatility, with negative effects on production. "I want to bring to your attention that the ratcheting up of taxes in the oil industry was partly brought on by the insistence of the IMF [International Monetary Fund]," he told OGJ.

And perhaps because the IMF's recommended monetary policy focused on increasing hard-cash reserves-needed to secure loan commitments-Moscow and local administrations may have been compelled to seek out those projects with an established revenue stream, such as Polar Lights.

"Every time the IMF made such recommendations, the result was invariably a decline in production, and, naturally, the Western companies were stuck in the same situation," Khodorkovsky said.

Foreign investment

For non-Russian investors to find an investment solution in Russia, Khodorkovsky said, there are certain routes they can take successfully. "But you need to make the right choice and move properly along the way you have chosen," he cautioned.

These opportunities include offshore production projects and asset swaps. "International oil companies can undoubtedly develop offshore production projects in Russia [Barents Sea, Caspian Sea, Sakhalin Island]. They are very competitive in this area because Russian companies do not have such experience."

In addition, Yukos is still willing to sell part of the company's assets (Fig. 5), just as before. However, the company formed its core strategy for that investment vehicle 5 years ago. Today, increased cash flow, a better idea of core-property values, and improved knowledge of how to generate more value from these assets provide the company with other options.

"Now we're interested in international investments, so [we] are ready to swap. We are ready, willing, and able to learn how to operate in the international market," he said. "Having said that, we are not prepared to admit that our Western colleagues work better than we do in Russia. We are ready to take a look-without prejudice-at how they do it. But we demand proof that they work better than we do."

"Five years ago, money was the most important thing for us. The industry was extremely inefficient, cash flow held us by the throat, and there was nothing else that we thought about... Today, we understand the most important thing is knowledge and are looking to acquire this knowledge at the best price."