Opportunities evolve from Venezuelan gas sector reforms

The natural gas sector in Venezuela has recently undergone a profound change as a result of regulatory reforms launched in 1999 by the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM).

One of the fundamental objectives of the new reform is to reduce the monopoly of Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state oil and gas conglomerate, in natural gas upstream, downstream, transmission, distribution, and marketing activities by opening all of these to private investment.

A second objective is to accelerate the creation of a more competitive and efficient market that can provide a strong base for the Venezuelan economy and stimulate its growth.

To participate in upstream projects, companies must compete in a bidding process-either alone or in consortia-designed to select the "most competent" to explore and develop nonassociated gas resources in 11 blocks strategically located near distribution and market centers. This process began in September 2000 and will last until March 2001. The deadline for submission of bids is the end of January 2001.

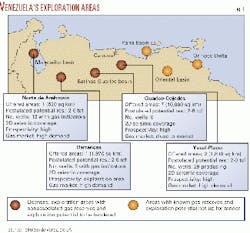

Upstream, private investors will be able to choose from nine exploratory areas having high potential and two areas labeled as having "proved reserves" (Fig. 1).

For downstream investors, in addition to the open-access policy that MEM has adopted, there will be bidding to acquire some of PDVSA's existing businesses such as transportation and distribution infrastructures.

So far, little is known about which infrastructures PDVSA will divest, except for large pipeline and gas compression projects to be bid later this year.

Particularly important to those interested in the downstream business is the need to be knowledgeable about the structure of the market and the existence of gas underpricing practices.

This article provides a synopsis of the Venezuelan gas industry and the new reform. Upstream, it includes exploration aspects of Venezuela's gas basins and of key areas to be offered. And downstream, it highlights the structure of the domestic market, its efficiency, and the way in which new reforms will affect the activities of participant companies. It also suggests improvements that could to be made in the new reform to guarantee the success of the Venezuelan gas industry.

Venezuelan gas habitat, risks

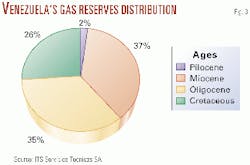

Venezuela's proven gas reserves stand at 4 trillion cu m, 91% of which is associated with oil. This puts Venezuela in seventh place worldwide but also places the nation in a difficult position, as oil exploration and exploitation projects almost always involve production of the gas reserves.

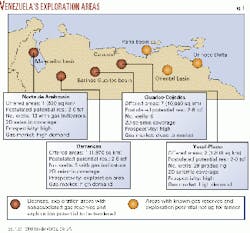

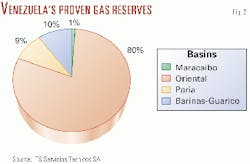

The Oriental, Barinas-Guarico, and Paria basins are the richest basins in terms of gas reserves (Fig. 2). About 85% of the proven reserves are located in 18 giant fields, most of which were discovered before 1960 (Table 1).

Gas production has begun from fields in the Oriental, Maracaibo, and Barinas-Guarico basins, but there is no production from the Paria basin. Although these last two basins are underexplored, compared with the Oriental and Maracaibo basins, they contain most of Venezuela's nonassociated gas reserves. It is estimated that more than 1 trillion cu m of gas remain to be proven in other frontier exploration areas such as the Orinoco Delta and offshore Venezuela's northern coast.

Of the 11 blocks MEM will offer for upstream activities, 10 are located in the Barinas-Guarico basin. These include two blocks in the Yucal-Placer area, where two giant fields having reserves exceeding 2 tcf also have exploration potential; seven blocks in the Guarico-Cojedes area; and one block in the Barrancas area.

All of these blocks were selected because their proven gas reserves are nonassociated and because any exploration potential there likely will lead to the discovery of nonassociated gas. The 11th block also is exploratory and is located in the well-known Maracaibo basin.

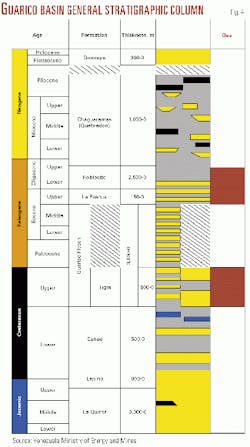

The basic petroleum habitat of the lesser-known Barinas-Guarico basin consists of Cretaceous and Oligocene-age sandstone reservoirs, Late Cretaceous-age, proven marine-source rocks, and pre-Miocene to recent-age, high-relief structural traps-mainly reverse anticlines and tilted fault blocks (Fig. 3).

Although the area of the basin exceeds 200,000 sq km, fewer than 200 gas wells have been drilled. Some of the known critical exploratory risks include the presence of integral structural closures, charge limitations, and reservoir effectiveness.

Drilling operations in the Barinas-Guarico basin can also be difficult. One vivid example is TotalFinaElf SA predecessor Elf Aquitane SA's experience in the former Guanare Block located in the Barinas basin. In 1999, the company drilled an exploratory well in the Guanare Block, and it took six bits just to drill 1,500 ft of the Paguey formation. The well was targeting the Cretaceous (typically located at 10,000 ft in the Barinas-Guarico basin), but the company found no hydrocarbons (Fig. 4).

The previously mentioned risks are likely to be present in most prospects in the Barrancas and Guarico-Cojedes areas and other parts of the Barinas-Guarico basin. One of the main geological risks of exploring in the Barinas-Guarico basin is the fact that, since the Paleogene, the entire basin has been subject to intense, high-temperature tectonic events highly detrimental to hydrocarbon prospectivity in terms of maturation and preservation. Having said that, it is obvious that the Barinas-Guarico basin remains very much underexplored, but some of the risks also remain high. The results of specific exploratory campaigns and the fact that at least two giant gas fields have been found in the Yucal-Placer area should provide a strong base to evaluate the areas to be offered.

Venezuelan gas market structure

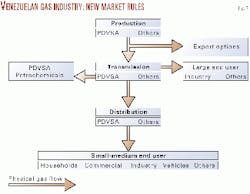

The Venezuelan gas market is the 19th largest in the world in terms of volume; total volume produced and consumed in 1999 was 32 billion cu m (Fig. 5). But the market is neither diverse nor competitive, because PDVSA is the only supplier, and there are few types of customers (Fig. 6).

Because a very large portion of the gas produced is used by PDVSA itself for gas reinjection and other field-related operations, however, any new gas found and produced is almost guaranteed to have at least one important client.

For example, many of the oil fields in the Maracaibo basin have a gas deficit-Venezuela's oil production has increased 7%/year since 1988, almost equal to the increase in gas production. About one third of the total gas produced is sold to industrial and commercial customers, the largest proportion of whom are industrial end-users. The main industrial end-users are located in the industrial states of Carabobo, Aragua, Anzoategui, and Guayana, and many are government-owned companies, particularly metallurgic customers in Guayana.

Other large industrial end-users include electric power generation companies. Industrial customers receive compressed natural gas gas through PDVSA's pipeline network- more than 4,000 km nationwide. On the other hand, commercial end-users are mainly LPG consumers that use LPG for cooking and transport fuel. LPG for household use represents a significant part of the commercial market, particularly in highly populated cities.

LPG is delivered in standard LPG containers and is distributed and sold by private companies, many of which have been in operation for many years. LPG for vehicles is a fairly recent alternative and represents only a small market.

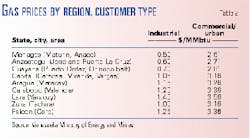

For industrial and commercial end-users, the price of natural gas, regulated by MEM, varies according to geographical region (Table 2). Under the new law, MEM will also regulate a maximum price.

As previously mentioned, the price of gas in Venezuela is heavily subsidized both by indirect and direct mechanisms. This subsidy is estimated to result in a final end-user market price that is 20% below real market-based levels.

Underpricing to encourage energy consumption is common in many developing countries, particularly in producer countries. The new law aims to break this deadlock, but it will not be a simple process because it is very much a political issue. If the new reform resolves pricing issues, the size of the market should be sufficient to draw the attention of international investors.

Hurdles to investment

The new gas reform will help develop the Venezuelan gas sector, and the new reform can be improved, but both will depend mostly on the way interested companies actually conduct their business after the gas market becomes liberalized.

The new reform put forth by MEM is a very positive step, as it defines a clearer set of rules and allows freer participation of the private sector in different parts of the gas business chain (Fig. 7). It is believed that the reform draws experiences from the successful Argentine gas reform and UK system, but a careful analysis suggests that it still has some flaws that affect the government and the way companies should behave.

In addition to upstream and downstream activities, the new reform includes clauses relating to wellhead price determination, export projects, LPG commercialization, and antimonopoly practices, among others. The new reform also calls for the creation of an autonomous agency-the Ente Nacional de Gas (ENG)-that will, presumably, have independent regulatory authority in all downstream aspects of the gas sector. Until now, all of these reforms sound good, so where are the flaws?

First, the government intends to take a 20% royalty in every upstream gas project. Venezuela is one of the countries with the highest aggregate tax levels in the world (~85%).

Gas upstream projects are vulnerable to high tax levels because they are not as profitable as oil projects, which generally finance gas projects. As a result, international companies with international portfolios that enter into, for example, a gas project in an underexplored gas province such as the Barinas-Guarico basin will prefer to invest in less-taxed projects in basins with lower risks where the risks and rewards are balanced.

A good example is Nigeria. Nigeria's gas reserves are 3 trillion cu m, and the political situation is one of the most delicate in Africa, but Royal Dutch Shell alone has religiously invested over $10 billion in that country.

The level of tax in Nigeria has been reduced substantially and is now, on average, 60%. As a result, Nigeria is the third country in Africa to have an LNG export plant. Therefore, high aggregate tax levels will have detrimental effects on the level of commitment a company is willing to make, regardless of the country's political situation or how large the reserves or potential reserves might be.

Second, a bidding process based mostly on a minimum-work program-which company has the best technology and financial muscle-is not as efficient when compared with a bidding process known as a "Dutch auction," which combines a signature bonus plus other benefits such as a minimum-work program.

The first type, which is the process to be used in Venezuela, results in a negative effect on both the companies and government, when compared with a Dutch auction. Dutch auctions encourage successful bidders to work harder and to be as efficient as possible to try to recover, in a short period of time, the capital invested. This will lead to the use of the best technologies and field optimization practices that are also some of the objectives of the new law.

But the first type of process (no signature bonus plus other incentives) will encourage companies to use all the time allowed in the license (5 years in this case for the exploration phase), because the financial and psychological pressures are much less. This process does not lead to the most optimal financial and technological practices.

Therefore, a no-signature bidding process will not only put the project in jeopardy but will also result in a greater chance of the company pulling out more easily from a contract at the expiration date. The company unknowingly may even withdraw from a project that could have been a giant field-there are real cases of this in Venezuela.

Finally, the influence that PDVSA will exert in the market will undoubtedly prevent other competitors from playing by competitive market rules (Fig. 7). To give an early start and partially guarantee the success of the Venezuelan gas industry will require that PDVSA divest more than 60% of its gas infrastructure assets and even upstream assets.

Unfortunately, even with such a hypothetical divestment, gas will still be competing in the internal market to a certain extent with other fuels, such as diesel and gasoline, in which PDVSA is the market leader. This results in unfair competition.

The obvious solution is that MEM also completely opens the market of other fuels-which is happening slowly-withdraws all price controls, and reduces PDVSA's market dominance through privatization. This may seem an impossible task, but those who lived on the other side of the Berlin Wall also once thought the same.

Room for improvement

There are several points affecting government and companies in the new law that could be improved. One of them is prohibiting private entities from participating in more than one sector of the gas chain per region. The intention of the government is to reduce the formation of monopolies.

However, the nature of the gas industry requires the creation of incentives for vertical integration of the different businesses in order to optimize the use of resources, reduce the final costs for the consumers, and maximize profits for the investors.

The best way to prevent another monopoly is by facilitating the free flow of competitors and having a strong watchdog agency such as ENG. Although the regulations provide for exceptions to be given for vertical integration, it clearly says that those will be granted if this is the only way in which the project can survive. It is important to differentiate between survival and optimization.

Another issue is the fact that licenses through auctions will be granted for transportation and commercialization. An auction process is logical for upstream projects, but not in transportation or distribution. In this case, barriers that impede the entrance of new participants should be avoided.

Nevertheless, the new law allows companies to request a permit to participate in downstream projects. Therefore, there doesn't seem to be any benefit to restricting the number of places in the market through an auction.

Another point is the fact that the tariffs are controlled and based on the principle of return on capital investment. This methodology encourages the overinvestment of the players, which leads to the inefficient use of capital.

The new law requires that tariffs be reviewed every 5 years, which could prove to be a very long time before the government realizes that tariffs have not been set properly. For example, in Argentina, where gas sector reforms have been highly successful, the incorrect timely adjustment of tariffs has caused some disruptions in the efficiency of the market.

In Argentina, in addition to tariff-adjusting problems, the biggest disappointment of the reform process has been the lack of competition in gas supply, as Repsol-YPF SA predecessor YPF SA, despite its divestments of assets before privatization, remains the dominant producer of gas and competing sources of fuel. Like PDVSA in Venezuela, Repsol-YPF in Argentina can impose prices and pricing formulas on multiple competing fuels, which results in market manipulation.

One way to increase competition in the now-privatized Argentine gas market-and in the soon-to-be Venezuelan gas market-would be the growth of exports through government granting of exploration and production concessions.

Under the new Venezuelan law, export projects such as those based on LNG and gas-to-liquids are welcome, in addition to possible pipelines to other markets in South America. Several companies have shown interest in gas export projects, particularly LNG.

Risks, rewards

The implementation of a new gas reform provides exciting new opportunities for everyone. Exploration risks are high-and minimal in the areas having proven reserves-but if upstream companies adopt an ambitious, well-balanced, and realistic exploration and investment strategy, the rewards could dwarf the risks involved.

Unfortunately, there is an example in Venezuela where a well-known company willingly invested $400 million in drilling development wells and a top-of-the-line production infrastructure without having completed a basic appraisal program. When the company discovered that reserves (in this case, oil) were not sufficient to cover the investment already made, the geology, contractual terms, and legal environment were the first to receive blame; this story is repeated over and over.

In the downstream sector, the Venezuelan market is large, but its early success will partly depend on how much of its infrastructure PDSVA is willing to divest and how many new participants with new projects actually participate.

Investors in the upstream, transmission, and distribution sectors should be comforted by the fact that there will always be internal demand for natural gas as long as there is oil production. The transition from a monopolistic to a competitive market will not be easy, particularly when setting new gas prices, but the new law, backed by a willing MEM and possibly a strong watchdog agency, could ease such transition.

Finally, although structural and framework reforms have been successful in other countries, and they may not equate to those in Venezuela, this does not necessarily mean that the Venezuelan gas industry will not succeed.

In fact, experience in several countries shown in International Energy Agency studies suggests that there is no catch-all prescriptive model for the process of regulatory reform and restructuring in the natural gas sector to ensure the success of the industry, nor for the ultimate regulatory framework once competition has been established.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the management of ITS Servicios Tecnicos SA (Caracas) for allowing use of data from some of the country studies, and Pablo Galante (the Economist, London) for providing ideas and reviewing part of the article.

Bibliography

Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM), 2000, Caracas, Venezuela (www.licenciasgas.com).

World Energy Outlook. (1998) International Energy Agency, IEA (www.iea.org) 1988.

BP Amoco Statistical Review (2000) (www.bpamoco.com).

El gas con urgencia financiera, (2000) Barriles (a bimonthly publication from the Venezuelan Petroleum Chamber), Caracas.

Gas basins of Venezuela, (2000) ITS Servicios Tecnicos SA Caracas, unpublished study (www.its.com.ve).

PDVSA Gas, (2000) (www.pdvsa.com).

Regulatory Reform in Argentina's Natural Gas Sector, (1999) International Energy Agency, (www.iea.org).

The author-

Ivan Sandrea received his BS in geology from Baylor University in 1996. During 1996-99, he was an exploration geologist and commercial analyst in Venezuela and an operations geologist in Norway for BP PLC. In 1999, Sandrea left BP for Edinburgh University, where he earned an MS in petroleum geology in August 2000. In 2000, he also was a gas market consultant to BP Egypt in Cairo. Sandrea's areas of focus include exploration, geology of gas resources, the gas exploration potential of Latin America and Africa, and the liberalization of gas and power markets in Latin America and Southern Europe. At present, he is attached to the geology and geophysics departments in Edinburgh University for studies relating to petroleum exploration, and he is working there towards an MBA.