Mexico's natural gas pricing crisis: Will confrontation lead to policy liberalization?

This article was provided as a late-breaking adjunct to OGJ's North American Gas special report, which begins on p. 58.

For the first time since 1976, a change in presidential administration in Mexico on Dec. 1, 2000, did not provoke a meltdown of the Mexican currency, evidence of the astonishing growth in confidence and the soundness of economic policy of former Pres. Ernesto Zedillo and his key advisors, principally Guillermo Ortiz and Luis Téllez.

Just as astonishing, given the budgetary and staff resources assigned to it during the Zedillo administration (1994-2000), has been the post-inaugural meltdown in the credibility of the government's Houston-netback pricing policy for natural gas.

A confrontation between Mexico's industrialists and policymakers over unexpectedly high natural gas prices is stimulating consideration of old and new options. A basic conclusion is that Petréleos Mexicanos' gas marketing policies during the Zedillo administration had the unintended effect of giving political ammunition to industrial groups to portray both Pemex and Mexico's Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) as out of touch with Mexican realities.

Industrial users in Mexico's northern region are demanding that the government impose a "Mexico price" of $3/MMbtu for natural gas, which reflects the competitive price that Mexico's international competitors pay for their gas in markets other than South Texas. Mexican Pres. Vicente Fox, meanwhile, says that, if the constitution were to permit it, he would favor an opening for private exploration and production investment for nonassociated gas in the Burgos basin.

Background

Since the administration of former Pres. Carlos Salinas (1988-94), one of the cornerstones of Mexican economic policy has been the intention to eliminate subsidies in public goods and services.

In 1992-93, as part of the negotiations that led to the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico agreed that it would not subsidize exports by setting energy prices lower than prevailing market prices. In 1995-96, CRE, with the consultation of Rice University economists, devised a methodology for pricing natural gas in Mexico by reference to prices in the Houston Ship Channel (HSC), which was seen as the relevant market reference.

This approach gradually gained acceptance with Pemex, the Mexican government and Mexican heavy industry and by May 2000, the final regulatory and contractual hurdles seemed to have been cleared.

But that was when the price of gas was $2.40/MMbtu. In the summer of 2000, the price of gas doubled and tripled before reaching $10/MMbtu Dec. 5, provoking the permanent closing of the Tepeyac Glass Co. after 54 years of commercial operations. Mexican industry complained to the government about what it considered unfair pricing practices imposed by CRE's pricing formula. One of the points was that Pemex should price its gas according to production costs, plus profit, not according to market benchmarks. The main complaint, however, was that the CRE's formula for gas pricing was misguided.

In August, CRE and Pemex announced that those companies that, by the end of the month, had signed up for futures contracts for the period September 2000 to February 2001 would be entitled to a 25% discount off the HSC price for gas deliveries in August.

In November, Pemex offered additional measures to ease the cash-flow problems of its industrial gas customers, including a decision not to apply surcharges to customers who missed their contracted quantity at any point from November 2000 through January 2001. The grace period for payment was also extended an additional 30 days beyond the regular 22 days.

Meanwhile, in November, the Energy Ministry had completed a study, The Present Situation of Natural Gas in Mexico, which noted that, in 1994-99, demand for natural gas in Mexico had increased by 6% annually. Electric power demand had increased at an even higher annual rate, 9%, based in large part on the increased use of combined-cycle turbine technology that requires natural gas. The authors, citing Article 26 of the Federal State Enterprises Act of 1986, noted that any product or service for which there is a prevailing market reference should be priced accordingly. The study concluded that the price of gas in Mexico should be based on the prevailing price in South Texas, adjusted for logistics costs: "Not to take the international reference price would be to open the door to arbitrage, which would threaten gas supply in Mexico."

At a seminar for petrochemical companies held in Mexico City on Oct. 16, organized by the Energy Program of the National University, one industry spokesman complained that "Pemex does not sell methane in Mexico. Pemex sells what they call 'natural gas,' referring to a mixture of gases, the price of which can be quoted in the Houston Ship Channel by reference to its heat value. Mexico's petrochemical industry wants to buy methane and does not want to buy any gas sold for its btu content."

Executives representing industrial gas buyers urged the government-which, on that occasion, was represented by Dionisio Pérez-Jácome (who, subsequently, would be named by the Fox administration to succeed Héctor Olea as president of CRE)-to consider alternatives. "The government should not just consider the price of a single link in the chemical value chain, that is, the price of natural gas, but the entire value chain," an industry spokesman said. "The government should price gas so that the Mexican petrochemical value chain is competitive in world markets."

Appeal for intervention

By mid-December, major industrial chambers of commerce, trade associations, and professional groups (including ANIQ, the association of chemical engineers) had held joint discussions of how to lobby the government for relief from what they regarded as unacceptably high natural gas prices.

On Dec. 22, an open (paid) letter was published in El Norte, the major newspaper of Monterrey industry, that appealed to "public opinion." The broadside made reference to a vote in the Mexican Senate on Dec. 5 that urged the government to find "alternatives for an immediate solution to the problem of the increase in the price of gas."

The groups contend there is a consensus in Mexican society for a "Mexico price" for natural gas that recognizes that Mexican-made products compete inside and outside of Mexico with international competitors, which in turn makes gas an advantage for Mexican companies.

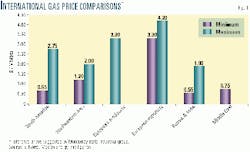

The chambers challenged the reasoning of CRE and its advisors and consultants: "Far from offering a price [for gas] that was really international, what is certain is that, to determine the price of our gas, what is being considered is [only] a regional market [South Texas]. To make matters worse, that market is subject to speculative pressures." Their key point was that, even if Mexican-manufactured exports were all exported to the US, in that market they would have to compete with products made in other countries where the price of natural gas is much lower (Fig. 1).

The chambers noted that those who opposed the concept of a "Mexico price" for gas, argue that there is an "opportunity cost, as if there were full interconnection [between the US and Mexico] and as if there were the possibility of exporting our gas. We know that on this point there are serious limitations."

The message for the government was that "6 months of anxiously waiting for a solution have meant the total and partial closing of some companies, the shutting down of production lines, the postponement of expansion projects, the loss of exports, cancellation of credit lines, [and] unemployment, as well as indirect negative effects for thousands of other jobs."

The document concluded that the solution to this problem needed to be an executive decision by the government-by implication, not one by any of the cabinet ministries, regulatory agencies, or government enterprises. The Mexican industrialists said they were "confident" that government authorities would mandate an "emergency price" of $3/MMbtu.

They warned that any higher price "would make it impossible to reactivate the affected companies while, establishing that price would give a breather to the companies in danger as well as their thousands of employees."

That same day, representatives of the chambers met with the new Energy Minister, Ernesto Martens, whose professional training had been as a chemical engineer. Martens, who, during the NAFTA negotiations, had been one of those who had argued to tie the price of Mexican natural gas to prices in the US market, was not convinced; the press reports the next day described the negotiations as having failed.

Response by Pemex

On Dec. 29, Pemex, by means of an open (paid) letter published in El Sol de México, provided a government response to its critics. Pemex announced a new, short-term program to ease the rising economic and political pressure associated with the high level of gas prices. The program had three points:

- Pemex would provide 4-year financing for gas billed at a price above $4/MMbtu (through Mar. 31).

- Long-term hedging contracts.

- A commitment to convene a special study group in January.

As of Jan. 2 and through Mar. 31, Pemex industrial customers would have the option of paying the regular market price of gas (as established by the CRE netback formula) or of financing that portion of their bills for gas quoted above $4/MMbtu.

In choosing the second option, the customer would have the right to defer repayment of the financed portion of the bill until April 2002. The customer would have 4 years to pay at an interest rate described only as competitive.

On Jan. 4, the Mexican press reported the Energy Ministry's price for January would be $9.50/MMbtu, implying that the amount that Pemex was offering to finance was $5.50/MMbtu (58%).

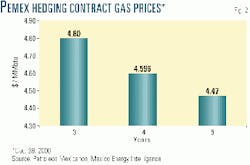

At the same time, Pemex offered customers long-term contracts to soften the volatility of the price of gas (Fig. 2).

The study group to be convened in January to consider additional measures would be made up of representatives of the Energy Ministry, Pemex, and its industrial customers. (No mention was made of including the industry chambers that had so strongly urged an executive decision by the government.)

Response by administration

The Fox administrattion made no public announcement until Jan. 5. Rodrigo Morales, chief of staff of Eduardo Sojo, stated at an industry forum in Monterrey that the new government did not contemplate granting any sort of subsidy to buffer the price of natural gas.

Morales specifically rejected the idea that Pemex would price gas according to its production cost, as Monterrey industry had repeatedly requested. The price of gas should be its "opportunity cost for the country," he was quoted as saying. He indicated that, in the near future, the government would propose an approach to gas pricing that would "minimize its cost but without generating subsidies."

On Jan. 7, a Jan. 3 interview with Fox was published in Mexico City daily Reforma and in other papers owned by a Monterrey-owned newspaper chain. In response to questions about natural gas supply and pricing, Fox said, "Of course, we would wish for the opening for [private] investment for nonassociated gas. For me, I would be pleased if tomorrow industrialists from Monterrey could invest and extract from the abundance of gas in the Burgos basinellipsebut the constitution, for the moment, does not let us."

Regarding gas prices, Fox treated the demands of industry as implicit demands for subsidies. "I have to be very careful in how I spend your tax money," he said in an imaginary conversation with a man-on-the-street who favors supporting the industrialists. Analysts noted that the comment, in "Fox-speak," rejects the demand that the government set a "Mexico price" for gas.

Repercussions

In its annual public opinion survey published on Jan. 1, the headline of Monterrey's El Norte's read, "[Natural] gas jeopardizes economic outlook." The report noted that the escalated price of natural gas had meant the closing of plants, the delay of projects, and the loss of thousands of jobs. For 43% of those interviewed, the increase of the price of natural gas was the "most exasperating"event of the year.

The problem of gas pricing in Mexico will not go away by Pemex's offer to finance the difference between the HSC price and $4/MMbtu. In the first place, Mexican industry had asked for a scrapping of the CRE formula for netback pricing, not just financing for the higher prices that its use implied. In the second place, Monterrey industry had asked for a "decision of the state" to establish a "Mexico price" for gas, not just a short-term program by Pemex to get by the next 3 months.

By the logic of Mexican politics, the confrontation between Mexican industry and the government will escalate, leading to more threats of plant closings and possibly marches and acts of civil disobedience by laid-off workers. José Antonio Rivero, president of the Mining Chamber of Commerce, noted on Jan. 3 that "while the [Fox] government came into the office with the goal of creating 1.3 million jobs/year, the high price of gas could bring about the loss of some 700,000 jobs in 2001 owing to massive plant closings."

Monterrey companies were reported on Jan. 3 as wanting to go back to their original proposal of $3/MMbtu as an emergency price while a new policy of gas pricing and production was defined. Alfonso Serna, representative of the influential chamber of Monterrey industrialists, Caintra, returned to the earlier argument about cost-based pricing: that "if it costs Pemex 60¢ to produce 1 MMbtu of gas, then selling the product at $3 is good business."

Because Pemex's proposed compromise on natural gas prices was announced during the holidays, just before the New Year holiday weekend, full consideration of the proposals by Mexican industry was not immediate. By Jan. 3, however, the shadow of things to come could be seen. "The mechanism proposed by Pemex 'would only prolong the agony,'" read a headline in El Norte. On the same day, Hylsamex, the steel subsidiary of Alfa, announced that it would close its sponge iron plant in Monterrey indefinitely, citing the 150% rise in the price of natural gas: "A price of $4/MMbtu continues to be very high for the company," a spokesman said. The plant closing would result in 1,200 layoffs.

By Jan. 4, however, Monterrey's views were known in full. Caintra Director Fernando Villarreal told a press briefing, in reference to the Pemex financing offer, "It is surprising that the government should propose financing as a solution, as, really, it is no solutionellipseIt is absurd that the government should not have a vision of Mexico in the medium and the long term. It seems that the only things that interest them are collecting taxes and in seeing that business fail." Villarreal said that he would seek appointments with the ministers of energy and finance and the Comptroller General-and, failing an agreement by that point, with Fox.

On Jan. 10, a full-page open letter to Fox was published in the Mexican press (El Norte and El Financiero), signed by the presidents of nine major industrial chambers of commerce and trade associations of Mexico. The letter consisted of a series of points against the government's position on natural gas pricing. The starting point was that, because imported LPG would cost $3/MMbtu if Mexico did not have gas and were not saddled with Pemex's monopolistic pricing policies, $3 should therefore be the maximum price for natural gas in Mexico.

The current price of natural gas, the letter said, put Mexico as one of the most expensive gas markets in the world. "The present policy of prices is suicidal," the letter warned, adding that Pemex's production cost, believed to be under $0.60/ MMbtu, was far below the current market price of $9.56, which represented an increase of 500% during the past year. The letter also challenged the "opportunity cost" argument espoused by Pemex, CRE, the Energy Ministry, and Rice economist and CRE consultant Dagobert Brito.

Brito pointed out that "it is not necessary, as the trade associations believe, for Pemex to be able to export all of its gas for the theory of opportunity to be applicable. It is only necessary that the marginal unit of production be available for export for the Houston gas hub price, adjusted for transportation, to be applicable to all of Mexico."

The letter writers warned of grave consequences awaiting the Fox administration and the outlook for economic development of Mexico unless the government reverses its course, drops all arguments about not wanting to give "subsidies" to natural gas consumers, and proposes a viable solution: "We have waited 6 months looking for solutions, and the problem has gotten worse. The government's proposals (financing, hedging) are insufficient, because they try to soften the immediate impact without attacking the fundamental problem, which is pricing policy."

Mexican politics, gas markets

As Mexican economist Fernando Ramírez observed, "In monopoly-controlled markets, you will always have periodic controversies and reviews around regulated prices. Some will argue for market prices; others will argue for prices based on a real or imputed cost of production. So the present controversy over natural gas in Mexico is a cyclical phenomenon that could erupt in relation to any commodity, the price of which is pegged to international benchmarks; gasoline pricing in Mexico would be another candidate for controversy."

Several Houston-based natural gas company observers agred with Olea's statement that, "Pemex Gas has a de facto monopoly on gas transportation," and that, until market control is liberalized, Mexican consumers will be penalized by distortions of supply and price.

"For gas market conditions in Mexico to be fundamentally changed, at least a new natural gas pipeline grid needs to be built that competes with Pemex's lines," a US pipeline company executive said. "In that way, every major gas consumer, such as a power plant, should have two independent sources of gas supply. An example would be GIMSA, in Monterrey, which distributes over 100 MMcfd. A company with that volume of gas requirement should have two sources of gas supply, not just Pemex.

"Until that happens, only the continuation of the pattern of begging for government relief will be expected," said a pipeline company analyst familiar with Mexico's industry.

The pipeline company executive noted that it was Pemex during 1994-99 that begged the government for relief from the threat of competition in gas transportation and marketing by asking that it maintain the import duty on natural gas. "Today it is Mexican industry, principally the Monterrey majors, who are begging for relief," he said.

Monterrey company criticism

Critics of the public posture of the Monterrey companies point out that to date those companies have turned down offers to build a new pipeline to their region because the delivered gas may be marginally more expensive than that offered by Pemex. This reluctance to support a competing line has meant that the companies have relied on Pemex and the government to manage their fuel cost. Only now, in the midst of a crisis, has Pemex proposed new financial instruments to help customers manage costs.

Another concern raised by one Mexican gas market analyst based in Houston is the extent to which Mexican industrial companies may be using the gas pricing crisis as an opportunity to fire workers without paying the heavy severance packages mandated by law (termination of employment associated with plant closure does not require a severance package).

Critics also point out that, for Pemex Gas, having a competitor pipeline would help solve the recurrent complaints about gas pricing.

Financial and market risks

A Houston financial analyst, reviewing the proposed terms of Pemex's offer to finance gas volumes priced above $4/MMbtu, observed that there are a number of risks for Pemex: "In offering to finance all Pemex customers, Pemex is taking on a credit risk. The matter of credit risk is related to how Pemex reports that risk. Will Pemex use GAAP [generally accepted accounting principles] rules to discount revenues for doubtful accounts or will all accounts be treated equally?"

Another matter raised is the interest rate that will be applied to the deferred amounts due, the financial analyst pointed out: "Will Pemex charge its cost of capital or the cost of capital that fairly corresponds to each customer? In the latter case, Pemex will have to invent a credit rating in some cases, as many Pemex customers have no access to bank credit at all."

On Jan. 4, the government announced that Pemex gas customers who opted for the deferred payment option would be charged an interest fee of 8%, compounded monthly.

In this situation, some observers believe that the current situation will make it more likely that industrial companies will stick with Pemex as their sole gas supplier, as Pemex's policy and track-record of bad-debt collection is weak compared with that of international companies.

A major oil company financial executive noted, "If a major Mexican company were to buy gas from a private gas marketer or transporter and then say that it should not pay because the price was too high, it would know that, the next week, lawyers would call, and the news would reach the Wall Street Journal that the company had reneged on its contract. With Pemex, in contrast, nothing is likely to happen, as Pemex (and the government behind it) can be effectively threatened with plant closings and layoffs."

And it's not clear that Pemex Gas takes the credit risk as much as does its affiliate Pemex E&P. "After all, what happens when Pemex Gas does not pay its bills to Pemex Exploration & Production?" he asked.

In choosing Pemex's long-term hedging option, a customer also entails a risk, the financial executive said: "Suppose the customer chooses a 3-year price of $4.80/MMbtu, and the price falls to $4 (see related story, p. 25). In that case, the customer owes Pemex 80¢. That new debt alone could provoke a financial crisis to a company."

Power struggle

Some Mexico analysts wonder if there is a subtext in the confrontation between Mexican industrialists and the Fox government.

For Ismael Martínez, a political analyst with ties to the Ibero-American University in Mexico City, "The striking point is that the Energy Ministry, Pemex, and the CRE are marginalized in the demands presented by industry, which wants direct access to the president and influence over industrial policy."

On Jan. 5, Mexican daily El Sol de México reported that the high prices of gas in Mexico had forced some companies, including the giant glassmaker Vitro, to consider moving operations to other countries, such as Venezuela or Trinidad and Tobago, where the current prices of natural gas are $0.66/MMbtu and $1.02/MMbtu, respectively.

E&P initiatives

Meanwhile, efforts to boost Mexico's own gas production continue to gather momentum.

Pemex at yearend 1999 launched its Strategic Gas Program (PEG), which is a comprehensive E&P effort devoted to helping Mexico develop additional dry gas reserves and production capacity (see related article, p. 70).

Since midyear 2000, some industry associations have urged the government to consider ways for private industry to participate in the exploration and production of natural gas.

This idea has also gained favor among some members of the Energy Commission of the Mexican Congress, as well as in some academic and legal circles, such as the Mexican Academy for Energy Law, but no public hearings or study groups yet have been formed to consider the option.

Change in the offing?

Some analysts believe that this crisis in the credibility of gas pricing philosophy is good for the Fox government, as a wake-up call on a policy issue that, under the Zediloo administration, received little attention.

"Pemex under former Director General Adrián Lajous was able to stare the government down and impose its own policies on natural gas imports, prices, and transportation policy," said one oil company analyst based in Mexico.

Pemex Gas, led in its marketing efforts by Felipe Luna, assured its customers that Pemex was offering the best terms and conditions available. Efforts to get companies to hedge Pemex's prices and the CRE's pricing rule generally failed.

"The corporate culture was not there to support the idea of hedging contracts," said Alejandro Gonzólez, currently an analyst with Cambridge, Mass.-based Cambridge Energy Research Associates, recalling his unsuccessful efforts over 2 years in the mid-1990s to sell such contracts in Mexico while working for a New York bank.

While the gas price surge has called attention to the need for hedging contracts, the main question ahead is whether any Mexican company will choose to take control of its gas cost and manage the associated risk. If not, Pemex will remain the exclusive gas provider in Mexico.

Gas exports to the US?

Pres.-Elect George W. Bush has spoken in favor of Mexico increasing both oil and natural gas exports to the US.

Since 1984, Pemex has been only a day trader in the US market, avoiding long-term contracts. This reluctance has been driven mainly by a combination of the lack of gas storage in Mexico (the US market is Pemex's de facto gas storage system), as well as by a reluctance to make commitments that might leave an opening for third-party gas marketers in Mexico.

At present, Pemex's ability to supply gas for the domestic market is in question. Short of getting new players into the upstream that could look for gas below Pemex's cost structure or beyond Pemex's technology reach, it is doubtful that any significant quantity of gas would become available for long-term contracts to the US.

Energy policy options?

Regarding energy policy, the question ahead is how the government will finally come down on the issue of a "Mexico price" of gas.

The Energy Ministry has speculated the case that, if the government were to agree to $3/MMbtu, some Mexican companies would conclude that it would make more money exporting the gas to the US market for $9/MMbtu, rather than consuming it in their own plants to make products. In such a scenario, the domestic gas supply deficit increases and the $3 price becomes unsustainable.

Regarding the alternative strategies to increase aggregate gas supply in Mexico, options such as coalbed methane, various gasification schemes, LNG imports, and private E&P all would need time and political capital. Assuming there were no regulatory or legal obstacles-which is not the case in several of these examples-it would take most of 2 years for any of these infrastructure projects to be developed.

But the situation cannot remain static. Mexican industrial users are serious about wanting to have a say in how Mexican energy policy is crafted. For Pemex, the best policy would be to reverse engines in natural gas marketing; in a sense, corporate policies under previous Pemex administrations have backfired. To have discouraged the use of open access to pipelines; blocked the construction of a new, competing pipeline; and muscled out private investment in gas storage has resulted in private industry depending 100% on Pemex for its gas supplies, prices, and terms.

For Pemex and the government, such a relationship creates an unwanted by-product: political capital for Pemex customers to complain to the government, fire workers, close plants, and threaten to move plants overseas. For both Pemex and the government, it would be better if the dissatisfied parties could be told, "If you don't like Pemex's prices, you are free to buy from our competitors."

The Fox presidential campaign promised to make state-owned companies more businesslike and competitive. It did not promise to turn them into welfare agencies for the benefit of large companies in Monterrey. Neither Pemex's CFO nor the Finance Ministry can be pleased about the prospect of providing supplier credit to hundreds of large and small companies that lack a bankable credit rating.

The author

George Baker is a petroleum analyst and director of Mexico Energy Intelligence, an industry newsletter service. He is the author of Mexico's Petroleum Sector (PennWell, 1984) and articles listed at www.energia.com.