Managing exploration risk or planning for success

Developing an exploration plan that minimizes risk may be the most important step an organization takes toward a financially strong exploration program.

The development of such a plan requires an understanding of your organization's strengths and weaknesses. It requires an assessment of the distinctive competencies of both your organization and competitors' organizations.

It also demands that you assess where you want to take your company. You must assess whether that direction is in phase with your company's strengths. Corporate objectives must be fully understood and realistically attainable. Exploration economics of the plays that you work needs to be firmly evaluated.

Although these concepts may appear basic, most companies do not have a broad perspective of their exploration program. This may be in part due to the current dominance of nonexplorationists in high management positions. It may also be due to the loss of experienced and successful exploration managers over the last 20 years.

Corporate objectives

Defining corporate objectives is not as easy as one would think.

During the boom of the late 1970s and early 1980s major oil and gas companies unrealistically defined their objectives. For example, many companies limited their exploration to field sizes of 5, 10, or 20 million bbl in areas where the average field size is 1 million bbl or less.

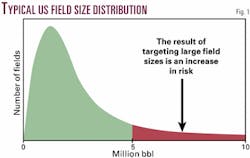

Fig. 1 represents the distribution of oil field sizes in the US. This figure demonstrates that by limiting the exploration target size a company dramatically reduces potential for success.

In this case the total area under the curve represents the chance of completing a successful well. The chance of falling within the smaller shaded area is proportionately less. If the overall chance of success is 20%, the chance of being in the small shaded area of the graph is on the order of a few percentage points. For that reason, exploration economics must address the entire field size distribution of the plays that a company tackles.

A company must be comfortable with the average result of an exploration play. Statistically speaking, it is nearly impossible to discover only large fields in a play distribution that is diverse.

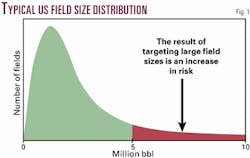

Consider the risk reward relationship of different regions of North America (Fig. 2). The relative position of the regions and play types on the graph is defined by components such as exploration risk, field size, and political risk. Plays in individual basins can also be compared in this way.

How your company fits on this graph depends on the distinctive competencies of your company. The way your company balances the regions on this graph defines your risk reward potential. And it defines your portfolio risk.

Distinctive competencies

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses is the first step in designing your exploration program. Strengths and weaknesses may include such factors as staff technical abilities, scientific facilities, exploration economics competence, corporate structure, competence of land staff, acreage position, and ability to raise capital.

This assessment is subjective, and it may be useful to benchmark your company against others that you feel have similar objectives. How is your company similar to or different from these benchmarked companies?

After assessing the distinctive competencies of your organization it may be necessary to either alter your goals or change the structure of your exploration organization.

Barriers to entry

Capital investment in plant, equipment, and personnel are effective barriers to competition in oil and gas just as they are in every other industry. Companies must understand the barriers to entry in all of the plays in which they operate.

Your level of performance over time will be consistent with your ability to address how your distinctive competencies meet the barriers to entry.

For example, if you don't own your own data, you don't generate your own prospects, and you don't possess competence in seismic interpretation, the number of plays in which you can be competitive will be limited. The number of competitors you have is going to be large.

In this example the barriers to entry for your business are small and your return from exploration will be small. Exploration of this type may be appropriate for privately owned companies that buy and sell acreage positions or invest in low-tech exploration plays such as coal degasification.

The plays of many small to medium sized companies have substantial barriers to entry. These include the development of strong technical staffs, seismic capabilities, and strong economic evaluation skills. These companies develop expertise in their staff over time that increases financial performance and serves as an effective barrier to entry. This effectively limits the number of competitors and increases the potential for success. Barriers to entry may be continuously increased as personnel training and development are increased.

Large companies have huge barriers to entry such as large land positions and substantial seismic and scientific capabilities. These large barriers to entry limit competition in the areas they work. Their large capital investments and their large size also limit the plays in which they can effectively compete. In effect small companies have organizational competence that limits competition from the majors.

The dangers of attempting to compete across barriers to entry cannot be understated. Companies that do not invest in personnel and technology will not be competitive against companies that have invested more wisely.

Diversification

Diversification reduces risk in exploration just as it reduces risk in the stock market. Portfolio diversification involves focusing on a number of different play types. It also involves product diversification.

As we have recently seen, the trends of oil and gas prices can diverge substantially. Having a broad exploration focus rather than a singular focus reduces overall market risk. Highly diversified energy companies have far less stock price volatility than those of single product companies.

Diversification can also be achieved by operating in different regions or countries where product prices may be independent.

Companies that are diversified and manage portfolio risk appropriately will eventually consume companies that are not diversified.

An example

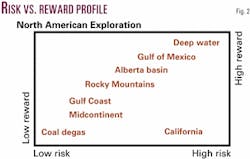

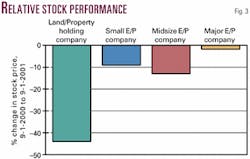

Fig. 3 depicts graphically the annual change in stock prices of several types of exploration companies.

The Land/Property Holding Company represents the type of company with the least technical competence. It has lost 43% of its value in the last year. This is not entirely due to its lack of distinctive competence. It operates in a sector of the business with few barriers to entry. The coal degasification company has chosen not to develop a diversified portfolio of products and properties to minimize risk.

The Land/Property Holding Company and the Small Exploration/Production Company have roughly the same market capitalization. The Small Exploration/Production Company has strong technical competencies and a diversified portfolio of properties and exploration targets that help to limit overall risk.

The other two highly diversified companies have done a great job of managing their exploration and property portfolios. They work in areas with substantial barriers to entry and therefore have fewer competitors and a greater potential for financial success.

Developing a realistic exploration philosophy may be the most important step that a company takes in achieving success. It involves setting goals that are realistic and that match the strengths of a company. Exploration economics must be approached with a broad perspective that addresses a complete play. Exploring for targets in only one portion of a field size distribution is probably not going to be successful.

Portfolio management is a basic element of risk management. It is essential that a portfolio of properties and exploration targets be developed that minimize market risk due to commodity price variation.

The author

Dan L. Wilson is a geologist, management consultant, writer, and a former area and district geologist at a major oil company. His corporate background includes planning and evaluation experience. He received an MS degree in geology from Western Washington University and an MBA from the University of Colorado at Denver. [email protected]