GIS-controlled workflow

In the industry's effort to bring oil and gas to market faster and cheaper, petroleum professionals have successfully applied a wide range of information technologies in their work. Essentially, these technologies interactively affect two entities: the data we work with and the people who do the work.

Unfortunately, as the industry searches for a better means to transform the data stream into information and knowledge, petroleum professionals are trying to overcome hurdles involving nonstandardized software programs and data formats (OGJ, Nov. 30, 1998, p. 58). Worse yet, disparities among the data and software applications promote segregated decision-making as bits and pieces of data are lost from upstream to downstream work activities.

For example, many reservoir simulators cannot incorporate all structural elements produced in a geologic mapping program, nor can most accounting programs utilize decline curve analysis to predict net present value. And as this loss of data continues on through marketing and management, it leaves only a trail of data "bread crumbs" that in many cases can be lost forever.

The glue

One company, however, offers what it claims is a solution that integrates the data stream with workflow procedures. Geoscience Earth & Marine Services Inc. (GEMS), Houston, a company that provides geologic hazard and risk assessments, uses geographic information systems (GIS) as a catalyst to tie different data types and different software programs together.

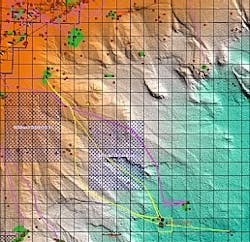

For example, Dominion E&P Inc. and GEMS used GIS as a preliminary pipeline planning tool for the Devil's Tower prospect located in the Gulf of Mexico (see image). "The old method of planning would have been to draw a straight line from the prospect to a possible host platform, followed by a field survey of the route to determine suitability," explained John Brand, a geologist with GEMS.

"Using GIS, however, we immediately identified a number of features that made the straight route undesirable. These features included man-made infrastructures and topography that would have made this route technically infeasible." In other words, a straight-line route would have crossed pipelines, wells, and an explosive ordnance dumping area.

Software plethora

The data needed to evaluate these routes came from a number of sources, including government agencies and oil companies. "Each particular data set required a particular software program," Brand said. For example, Seismic Micro-Technology's Kingdom Suite contributed digitized geologic interpretations to GIS via AutoCAD and provided ASCII seismic attribute data to Golden Software's mapping program, Surfer.

"Surfer was then used to generate grids, such as bathymetry, seafloor amplitude, and positive-negative seafloor slope, depending on the seismic data." These grids were then imported into the GIS program MapInfo for final interpretation.

"If the software cannot directly provide the desired data format, odds are another one can," Brand said. Subsequently, a number of scenarios were designed to avoid the ordnance dumpsites and to minimize pipeline crossovers. As a cost alternative, other routes were designed to pass through the dumpsite while paying heed to steep or rocky seafloor.

"Each preliminary route is dynamic and can be updated 'on the fly,' so that attributes can be used to assess each route's cost-effectiveness," Brand said. The end result, however, is not only a controlled data stream from which no "data crumbs" are lost but also a system that allows all petroleum professionals in an organization to work with one another. This, in turn, leads to efficient workflow and true teamwork.