The Virtual Oil Company: Capstone Of Integration

The idea of a "virtual company" is not new. For years now, business theorists have envisioned a future dominated by enlightened companies that would focus on their core competencies, form strategic alliances with suppliers and business partners, and attack complex markets as if they were all one organization. According to theory, members of a virtual entity would benefit from one another's strengths while eliminating inefficient overhead.

Throughout the petroleum industry, I have heard many senior executives express the desire to create such a "virtual oil company." I have even participated in meetings with the goal of exploring the possibility. To my disappointment, however, I have seen no successful examples of the virtual business model in our industry, except in the context of isolated projects. Why have industry leaders failed to turn this visionary model into reality, even when they intuitively grasp its potential benefits?

Need never greater

In his book, Only the Paranoid Survive, retired Intel CEO Andrew S. Grove describes a business phenomenon that he calls a "strategic inflection point."

Occasionally a force of change, which he calls "a 10X force," places so much pressure on a business or an entire industry that a complete restructuring of the market occurs. A good example of a 10X force is the worldwide web. The web is irrevocably changing all of our lives, completely wrecking some companies while creating enormous opportunities for others. According to Grove, the arrival of a 10X force can be sudden-remember how Microsoft was caught "off guard" by the explosive growth of the internet-or it can sneak up slowly. Either way, the end result is the same. At some point, the universe of affected businesses is changed forever.

The point at which this dramatic change occurs is what Grove calls a strategic inflection point. Here the business reaches a peak, passes through a period of uncertainty, then companies either accelerate to new heights or-if the wrong path is chosen-slide into a decline from which most never recover.

I am convinced that, unlike the last great downturn our industry suffered in the 1980s, today we are right in the middle of the "choppy waters" of a strategic inflection point. The dramatic collapse of oil prices in 1998 was certainly an external catalyst for change, but the real 10X force at work today is the perception by most oil company executives that commodity prices could-on average-remain low for the foreseeable future.

The primary response to this 10X force can be characterized as a growing awareness that only the most productive will survive. That, of course, has unleashed a new wave of mergers that are larger than ever before. More importantly, it has finally forced oil companies to look for radical new ways of doing business.

In this "productivity race for survival," new strategies and business approaches are emerging in both large and small organizations, lead by industry innovators such as John Browne at BP Amoco PLC. New rules of the game are being written, and new players are moving onto the field. Executives around the world are scrambling to meet the new challenge.

Unlike the innovators, however, most oil companies are still depending on the old rules of the game. They are cutting costs by laying off hordes of people, attacking the service sector by squeezing out price concessions, and looking for "loopholes" in contracts to break their long-term commitments. Alliances and win-win business relationships typically go out the window as energy prices waver. All of these are familiar reactions when times get tough in our industry. Unfortunately, in isolation, none of these approaches are the right way to deal with a true strategic inflection point. Focusing on costs in the short term may be necessary, but alone it is insufficient. And if it is done incorrectly, it could do irreparable damage to a company's long-term competitive position. Those organizations that play it safe and keep doing things the old way will face an irreversible decline in business as they compete head-to-head with an emerging new breed of companies moving in radically different directions.

When the dust settles from this latest industry crisis, I suspect we will look back at 1998 as a strategic inflection point, and the years immediately following as the beginning of a new era. In the 1980s, visionary oil companies embraced new 3D seismic technologies to radically improve subsurface imaging. Today, a new breed of "virtual energy companies" is beginning to explore more-collaborative business models, leveraging new global information technologies to reinvent decision-making across the entire E&P life cycle.

Economies of knowledge

As energy companies both "informationalize" (or computerize) and "integrate" the business, they will dramatically improve collaborative decision-making processes throughout the virtual organization. Knowledge warehousing, data mining, enterprise software applications, and high-bandwidth telecommunication systems will lay the foundation for stronger decision-making by providing rapid access to expertise, information, and knowledge at any time and any place.

Imagine, for example, a production engineer preparing a complex frac job in a low-porosity carbonate reservoir in the US Midcontinent. If he could use a "search engine" to identify frac jobs run in similar carbonates elsewhere in the world and learn from existing best practices (and failures), he could design the job at hand far more efficiently. As energy companies begin to capture this type of knowledge more routinely, individual learning curves and project cycle times will shorten dramatically.

Sheer size and "economies of scale" will no longer ensure competitive advantage, as they did in the Industrial Age. Only those corporations that achieve "economies of knowledge"-regardless of size-will be able to compete effectively in the Information Age. In other words, the core competencies of such organizations will depend directly on the knowledge that resides in the heads of their interconnected people and their ability to capture that knowledge in dynamic information systems.

Oil services evolution

I believe the growing need to maximize economies of knowledge will fundamentally alter the current business model in the oil and gas industry.

In the "golden years" of the Information Age (c. 2000-20), when the ultimate value of computer technology is finally realized in all aspects of the business, economies of knowledge will increasingly differentiate energy companies from service companies.

Consider for a moment the evolution of the oil field service business. It has undergone two evolutionary phases to date, and a third is just beginning. In the first phase, regional and global oil field service companies formed primarily to bring the benefits of economies of scale-such as consistency and cost-effectiveness-to highly specialized services needed by many customers in different geographic locations.

The second phase of evolution was driven by the additional need for economies of scope. Oil field service providers found that numerous synergies, internal and external, resulted when a single company could provide multiple services. Even when the company maintained separate divisions, greater economic benefits were achieved by sharing administrative overhead, R&D, operating facilities, and marketing channels. These economies of scope are behind the drive toward integration in the service industry.

A third phase of evolution, begun recently, seeks to extend economies of scope to economies of knowledge across the integrated services business to create additional efficiencies. Innovative knowledge management technologies will soon enable oil field service companies to capture more experience in 1 day from core services across the globe (e.g., logging wells, building production platforms, etc.) than even the largest oil companies could capture in a year or more. As a result, diverging economies of knowledge will rapidly shift the "center of gravity" in oil field operations-including the "manufacturing-like" production of oil fields-away from the energy companies in the direction of the global, integrated service companies.

Of course, by focusing on selected niches in which they can gain economies of knowledge, oil and gas companies will continue to specialize operationally. Examples of this approach might include a regional oil company that specializes in being the low-cost producer in stripper wells or a multinational corporation with worldwide expertise in deep water engineering. In any case, to compete successfully, a company must be able to capture and leverage knowledge more efficiently and have a volume of activity comparable to or greater than other companies focused on the same niche.

Emerging centers of gravity

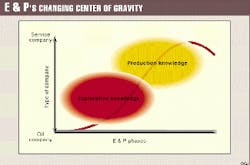

I believe two distinct "centers of gravity" in the knowledge economies of oil companies and oil field service companies will increasingly emerge, as more-robust knowledge management tools are implemented over the next few years.

Oil companies will probably retain the knowledge advantage in the exploration and early exploitation stages, as well as project management throughout the life span of a reservoir-and perhaps across the entire value chain from wellhead to pump or burner tip. The economies of knowledge associated with these activities revolve around managing risk, global relationship-building to gain access to acreage, and creativity in applying new technologies to frontier areas and early field development. Companies focused on subsalt exploration and the search for global analogs are a good example.

As oil and gas reservoirs move into early exploitation, energy companies still have economies of knowledge. Not only do they control current information on new well performance during reservoir delineation drilling, they are also the integrators of well, geological, and new production data. However, as oil fields move into full development and production operations, the center of gravity begins to shift in favor of the integrated oil field service companies (Fig. 2).

Oil companies that attempt to do business in areas where the economies of knowledge are against them will have a built-in competitive disadvantage. On the other hand, oil companies that leverage the expertise of their service providers by way of more-collaborative business models will gain the best of both centers of gravity.

Collaboration vs. outsourcing

The expression "center of gravity" is used deliberately to capture the idea that, in every phase of the oil field life cycle, both oil company and service company can add value if their roles are defined by their respective economies of knowledge.

In general, the oil company's knowledge will center around reservoir modeling and project management of the oil field life cycle at a macro level. The oil field service company's knowledge will center more around the development and deployment of technologies and services used to exploit the reservoir and project management related to those particular activities.

A business model that promotes collaboration between oil company and service company better leverages the knowledge of both parties than any outsourcing operation.

Outsourcing often assumes the service company can single-handedly provide a turnkey solution. In a truly collaborative model, by contrast, the oil company would own both the reservoir and associated earth model throughout the life of the asset. The service company might provide the information systems and technical support needed to create and store the earth model. It might even have controlled access to that model in real-time. But the oil company would never give up ownership. It would remain the macro-level project manager by choosing which service companies to use and managing the interfaces among all the parties involved. By doing so, it would become a true "virtual" energy company.

In a virtual enterprise, all partners and service providers would maintain highly interactive and collaborative relationships at every stage of the life cycle, from early exploration through late production. To the casual observer, it might even be difficult to identify which individuals work for the service company and which work for the energy company. But the underlying economies of knowledge will always be clear to the individuals themselves through access to and support of the particular decision-making processes associated with their home base.

Current model's shortcomings

At the Cambridge Energy Research Associates conference in Houston in 1998, L.E. Simmons, founder and partner of SCF Partners, an energy service company investment fund, presented an analysis of industry profitability over the past decade.

According to his calculations, the aggregate profitability of the oil company sector was 7% percent, while that of the service sector was 4%. Simmons stressed that even if these two figures were combined, 11% profitability would be insufficient to attract the kind of capital needed for the E&P industry to meet future demand. He suggested that, instead of constantly nibbling at one another's profit margins, oil and service companies need to join forces to reduce the costs that constitute 89% of the pie.

His suggestion highlights a basic, but easily overlooked, structural reality of our industry: that while both sectors ultimately depend on reservoir performance for their survival, from a business model perspective they are usually misaligned. This misalignment is played out in perpetual win-lose cycles characterized by alternating capacity swings driven primarily by commodity prices. The result is tremendous waste and inefficiency throughout the industry as a whole.

A primary point of contention has been the oil field service companies' desire to assume more responsibility for maximizing reservoir performance while reaping more of the rewards through various performance contracts. The service sector argues that it simply cannot survive or make the necessary investments to do its job without assurances of better profitability. In response, there have been "cries of outrage" from energy companies that the service sector is "crossing the line" into their business. The fear that somehow service companies would "morph" themselves into oil companies has been particularly threatening to individuals in oil companies whose roles have historically revolved around reservoir optimization.

In general, a lack of understanding of one another's needs is hampering both sectors from negotiating a new business model based on a true win-win position. Establishing trust and operating more as a partnership than a "master-slave" relationship seems almost impossible after decades of win-lose thinking. Even when negotiations begin with the idea of creating a new relationship, potential partners often end up adopting the adversarial approach so familiar throughout our history. The way some oil companies have searched for loopholes to break their long-term contracts with rig operators is a typical example of how deep a rut our industry is in.

Nevertheless, people are awakening to this problem, and new models of doing business between the two sectors are slowly beginning to emerge.

Virtual enterprise

Eventually, early adopters will find appropriate combinations of operational and business models that will dramatically lower costs and increase reservoir performance. Only by adopting a virtual collaboration model that strategically aligns both sectors will we significantly dampen the boom-and-bust cycles that have plagued our industry for decades.

The virtual enterprise of the future will be much more dynamic and sensitive to the need for tuning operational parameters of the business as a whole, including capital spending for both energy and service companies and optimizing the whole chain of value creation related to oil and gas reservoirs. This future world will be characterized by knowledge management and collaborative decision-making by way of virtual teams. Virtual enterprises will be empowered by a willingness to do business in more-productive ways and by information technologies that eliminate barriers between stakeholders and radically improve work processes.

As we strive together to turn this vision into a reality, oil companies and the service sector will rejuvenate our tired industry and rise to meet the energy challenges of the 21st century.

The Author

Robert P. Peebler has been president and chief executive officer of Landmark Graphics Corp. since 1992. Previously, he held executive positions including chief operating officer, president of Landmark's seismic products division, and vice-president of marketing. Before joining Landmark in 1989, he was president of his own marketing/management consulting firm. He also was employed in the oil field services business for 18 years. Peebler graduated from the University of Kansas with a degree in electrical engineering.