China's oil products demand: despite constraints, bullish for global crude

This article and the article by David Pietz on p. 60 were adapted from a study on the outlook for China's energy sector by ESAI.

During the last 10 years, there has been a great deal of excitement over the potential of China's growing energy demand to push regional and global oil markets to ever-new heights.

By and large, these euphoric forecasts have yet to materialize. The "China projections" ignored two key aspects of the Chinese economy in general and the oil sector in particular: 1) economic growth was unlikely to sustain itself at a double-digit pace; and 2) the intrusion of government policy was likely to inhibit demand.

During the next 10 years, these two factors are likely to continue to shape Chinese petroleum demand. Economic growth will not return to the "go-go" days of the early 1990s, and government policy, despite the apparent promise of China's accession to the World Trade Organization, will serve to restrain consumption by restricting supply.

Although important restrictions on the Chinese market will continue, the country's oil products demand will grow by roughly 4-5%/year. During the next 10 years, this demand will be met by domestically processing imported crude. This development will generally be bearish for regional product markets but bullish for the global crude market.

More sustainable growth

Much of the anticipation over China's energy future during the 1990s was generated by straight-line projections based on current growth rates of gross domestic product.

The problem with this rather simple extrapolation was three-fold:

- Chinese government growth rates probably overestimated growth by roughly 2.0-2.5 percentage points/year during 1978-1995.1

- Economic growth tended to oscillate from periods of acute growth followed by periods of slower growth.

- Forecasts for Chinese petroleum demand perhaps naively assumed that economic growth rates would continue at the levels of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

One of the most important factors in changes in energy use patterns in developing countries is per capita GDP (or simply, per capita income). Patterns of per capita income depend on overall GDP growth (and, obviously, demographic change).

Looking out over the next decade, the rather manic nature of Chinese economic growth will likely continue as the government only slowly develops the monetary tools to effectively manage periods of hyper-growth (accompanied by inflation) and stagnation (accompanied by deflation).

At the same time, however, growth rates will not reach the extremes of this spectrum, particularly the hyper-growth of the early 1990s. The primary reason is that the economic reform program has entered the critical stage of deep structural reform of state industries. Judging from the events of 1998 and 1999, reform will be a slow, long-term process.

Although the deliberate pace of the restructuring process will mitigate some of the necessary pain, the inevitable results-high unemployment, larger government outlays for social welfare, and slower consumer spending-are likely to be an overall drag on economic growth. As such, growth rates are likely to be moderate and move within a more narrow range during 2000-10 than in previous years (Table 1).

Intervention, consolidation

The other major determinant of future oil product demand in China will be government regulation of the oil sector.

That the oil sector in China is highly regulated may be stating the obvious, but during the past 10 years there has been an ebb and flow in terms of the degree that this regulatory control has been exercised. On two occasions, in 1994 and in 1998, the state stepped in aggressively to reassert control over pricing and supply to effectively reverse de facto liberalizing tendencies.

The experiences of 1994 and 1998-99 reflect the unique role that the Chinese government believes the petroleum industry holds within the economy. As the government loosened the overall controls of central planning during 1978-99, it reasserted the right to manipulate petroleum supply and demand to help regulate the overall economy.2

Although government rhetoric promoted the notion of petroleum market deregulation throughout the 1990s, the government quickly reimposed regulatory control over the industry in order to mitigate the inflationary pressures that petroleum consumption had on the economy (1994) and the deflationary effects of cheap product imports (1998-99). In addition, the government was keen to protect the domestic refining industry that contributes about 40% of all revenue remitted to the state by state-run enterprises.

So, in 1994 and 1998, the government slapped restrictions on crude imports and a ban on diesel imports and returned to a rigid fixing of domestic product prices. The effect was to limit demand by rationing supply.

From a larger perspective, 1994 and 1998 highlighted the fact that the relationship between economic growth and petroleum demand is not always clear in China. Largely because of bureaucratic intrusion in the Chinese petroleum markets, the ratio between oil demand growth rates and GDP growth rates has been highly variable. There is, however, a clear pattern of low oil/GDP demand elasticities during years when the government actively restrained petroleum supply, namely 1994 and 1998 (Table 2).

Will restrained economic growth, periodic retrenchment, and government intervention continue to influence petroleum demand during the next decade? We expect economic growth to moderate to more sustainable levels of 5-6%/year for the next 10 years.

As such, petroleum demand growth will slow, but it will be more predictable. Deregulation of the Chinese petroleum sector will make progress, but in the short-run (2-4 years), regulatory control may even intensify as China prepares its domestic markets for entry into the WTO. As a result, demand will remain susceptible to bureaucratic intrusion.

Macro-determinants

Aside from economic growth and government regulation, there are several other factors, or "macro-determinants" that will help shape petroleum demand in China during the next decade. In general, most of these developments have served, and will continue, to limit petroleum demand below many optimistic projections:

- Slower population growth. The "one-child policy," begun in 1975, has slowed the rate of population growth in China. During 2000-10, the population is expected to grow by an average of 0.7%/year. China's population is growing more slowly compared with countries at similar stages of economic development.

- Greater urbanization. The percentage of Chinese living in urban areas increased to 30% in 1997 from 18% in 1978. Con- tinued urbanization will mean substantial increases in residential electricity use.

- High but decreasing energy intensities. China's overall energy intensities will remain high vis-a-vis other developing countries but will decrease as reform of state-owned enterprises continues and more energy-efficient technologies are utilized.

- Changing structure of the economy. The percentage of China's total GDP derived from the industrial sector will slowly decline over the next 10 years. At the same time, energy use in the residential-commercial and the transportation sectors will increase most quickly.

- A gradual commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Despite much skepticism, central planners will forge ahead with more-stringent fuel and emission standards.

Individual product demand

Energy demand patterns in China are undergoing change but will continue to share several defining features.

These include high energy intensities, high consumption in the industrial sector, increasing consumption in the transportation sector, and rapid growth in electricity.

Individual products, however, also have unique demand dynamics. For example, gasoline demand is highly variable with personal income, while fuel oil is subject to government priorities relative to coal and natural gas.

Thus, aside from economic growth, there are a number of important factors that influence overall petroleum demand and consumption of individual products. The following sections elaborate on the demand potential for selected petroleum products.

Naphtha

During 2000-10, Chinese naphtha demand will grow by an average of 5.1%/year.

This growth will be highly variable from year to year, dependent on large periodic additions to petrochemical production. Indeed, the driver of naphtha demand in China will be aggressive expansion of the petrochemical sector. China's ethylene demand will more than double in the next decade, reaching over 10,000,000 tonnes by 2010.

China has increasingly identified the petrochemical sector for import reduction. Although the addition of new grassroots petrochemical facilities will be restricted through 2001, the government will continue to increase production by expanding existing facilities.

If economic growth rebounds more quickly than expected, then the government may quickly reverse its moratorium on new petrochemical production plants. The high rate of growth in domestic demand for petrochemical products, however, makes it very unlikely that the government investment in domestic production will keep pace. The consequence of this imbalance will be greater petrochemical imports into the country.

Nonetheless, a concern to reduce petrochemical import dependence will mean that domestic petrochemical production capacity will expand substantially. ESAI expects ethylene production to increase to over 6 million tonnes in 2010 from 4 million tonnes in 2000. This steady expansion will support strong naphtha demand in China.

Gasoline

During the next 10 years, per capita income in China will just begin to enter the critical threshold seen when automobile ownership took off in the newly industrialized countries in East Asia.

Yet most Chinese cities will likely have an inadequate urban infrastructure to support a large stock of motor vehicles. Much investment has been made in constructing "ring roads" in Beijing and other cities since the 1980s, and selected cities, such as Shanghai, have made enormous strides in expanding major arteries within the city to accommodate increased automobile traffic.

While these developments will provide support to greater automobile stocks, bottlenecks in urban transportation networks will continue to exist in most Chinese cities throughout the next decade.

Over the next decade, gasoline demand will increase by an average of 3.8%/year. These increases are below the pace of the 1980s and 1990s, primarily because of a slowing in overall economic growth.

What is significant, however, is that the elasticity of demand will increase over the next decade. In other words, during 2000-10, the ratio between gasoline consumption and GDP will increase. Why? While the slow expansion of urban infrastructure implies a cap to traffic growth, it will help sustain a moderate increase in motor vehicles.

Diesel

Over the next decade, further growth in freight traffic will continue to be the primary driver of increased diesel consumption.

Growth, however, will not replicate the tremendous increases of the past 10-20 years. By the mid-1990s, expansion of the highway system, total truck stocks, and other freight indicators had begun to moderate. This should perhaps come as no surprise, as growth in the 1980s and early 1990s began from an undeveloped base. In addition, overall economic growth rates during the next decade will slow from the double-digit days of the 1980s.

Solid growth of freight transport will primarily come from aggressive government investment in an intrastate road system designed to facilitate the development of domestic trade networks.

Diesel consumption in the agricultural sector will expand at slower rates, as the limits of mechanization are reached under the pressure of rural population densities. During the next 10 years, diesel demand will grow by an average of 4.8%/year.

Fuel oil

During 2000-10, we expect fuel oil demand to increase by an average of 3.6%/year, a higher ratio to GDP growth than during the previous two decades, but well below the demand of other products. The slightly stronger demand for fuel oil in the next decade will primarily come from growth in the industrial sector. Demand in the electricity generation sector will remain flat or continue its recent declines. Instead, coal and natural gas will be the preferred fuels for power generation.

Promoting domestic refining

Although government policy and slowing rates of economic growth will restrain oil demand in the next decade, growth in petroleum products consumption will occur.

How will this growth will be met? Will it be met by a corresponding increase in production or by product imports? ESAI thinks that the next decade will reflect a bias towards aggressively increasing domestic refined products output. In large part, this strategy will be motivated by a desire to maintain a strong domestic refining sector to reduce products import dependency.

The outcome of this policy is that it will necessitate large increases in crude imports. China's crude import requirements will grow by an average of 15%/year during 2000-10, reaching 1.9 million b/d by the end of this period. Virtually all of these incremental barrels will be sourced from the Middle East.

During 2000-10, the Chinese refining sector will be characterized by large capacity additions, increasing utilization rates, and a lighter product slate. Crude distillation unit capacity will almost double in the next 10 years, reaching a total of over 6 million b/d in 2010, an average increase of 2.7%/year. At present, there is a moratorium on new refining facilities until 2001, and additions before this time will be limited to expansions and additions to secondary processing units. After this time, capacity additions will come from both additions and grassroots projects.

Investment decisions are likely to be driven by concerns over import dependency. The key variable is diesel supply. As the most important fuel for economic growth, China has been, and will continue to be, concerned about security of supply. As such, there will be a limit on the acceptable volume of diesel imports. We think this ceiling is roughly 150,000 b/d. In other words, when petroleum planners anticipate a diesel deficit exceeding this figure, investment decisions are likely to be made to augment refining capacity.

During the past 10 years, refinery utilization rates in China have been low. An extensive network of independently controlled distribution and retail outlets were likely to seek products from other sources than state oil companies China National Petroleum Corp. or China National Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec), which sold products at high state-set prices.

Before 1998, these firms could secure cheaper imported products, or they could get cheaper products from small locally controlled refiners operating in China. If CNPC and Sinopec can eliminate domestic competition, they can eliminate alternative sources of product. By doing so, they can raise China's utilization rates. This is the goal behind the current government assault on small refiners, wholesalers, and independent retailers.

The government will be only partially successful in this campaign, because it may be unwilling (or simply unable) to apply the pressure necessary to eliminate local jurisdiction over all these businesses. But the government will be successful enough to muster sufficient control over domestic supply to be able to allow CNPC and Sinopec to raise utilization rates at their refineries.

Product yields will tend toward the lighter side of the slate, a trend that began in the mid-1990s. Diesel will experience the greatest increase in yield, rising to nearly 38% by 2010 from 30% in 1990. A lighter refining slate will be made possible by extensive investment in secondary capacity. With additional crudes sourced from the Middle East, investment in desulfurization capacity will need to be substantial to meet these yields. Stricter product specifications will also mandate greater investments in upgrading capacity.

Impacts of Chinese strategies

China's long-range strategic decision to import crude instead of products is a bearish development for the Asian refining business.

On one hand, increasing crude demand will support global and Asian crude oil prices, while on the other hand, limited petroleum product imports will weaken product prices, especially in the Singapore-based Asian market.

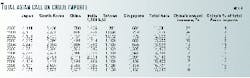

China's role in influencing the region's product balances is significant (Table 3) China will play a key role in Asian naphtha and fuel oil markets. Although we expect China's fuel oil deficit to shrink from the extreme levels of 1999 (as Chinese refiners focused on upgrading heavy oil to diesel), the overall trend by 2010 is for China to contribute heavily to the region's overall fuel oil deficit. China's contribution to the region's naphtha deficit is even more striking. China's growing naphtha deficit will reinforce the growing Asian deficit.

The influence of China on the Asian gasoline and diesel balances is comparatively bearish. For most of the decade, China will maintain a gasoline surplus and contribute to a weak Asian gasoline market. In terms of diesel, China will maintain an annual deficit averaging roughly 150,000 b/d. The fact that China's diesel deficit remains constant and is unlikely to grow without triggering new refining investments is generally bad news for Asian refiners that are hoping a growing Chinese diesel appetite would be a major bullish factor for the Asian product market.

During the past decade, there has been a great deal of anticipation of how and to what degree Chinese oil demand would shape the global crude oil market. As of the beginning of 2000, China's impact has been limited.

During the next decade, however, that will begin to change. China's crude oil import requirements will grow by over 15%, or 100,000 b/d/year during 2000-10. This will make China one of the fastest growing import markets in Asia and the world (Table 4). Global crude oil demand could grow an average of 1.4-1.5 million b/d/year during 2000-10. Of that growth, China will probably account for as much as 13-14%.

There is no other single country, except perhaps the US, that could register that large a contribution to global crude oil demand growth.

As China becomes increasingly dependent on crude imports, however, it is highly likely that China will increasingly face more-pressing energy security issues. How will China respond to fast-growing dependence on external energy sources? Beijing has already begun facing these issues as it has sought to secure crude supplies by investing in oil fields in Kazakhstan, Venezuela, and Sudan. In addition, China will aggressively seek the necessary capital to construct a supply infrastructure to import crude from Russia. At the same time, China will continue to look for ways to invest in the countries of the Persian Gulf (i.e., Iran and Iraq) in an effort to secure the flow of oil that does come from the Persian Gulf.

References

- Maddison, A., Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris, 1998.

- Horsnell, P., Oil in Asia: Markets, Trading, Refining, and Deregulation, Oxford University Press, 1997.

The author-

David Pietz is an analyst in the Pacific Basin practice of Energy Security Analysis Inc., Wakefield, Mass. With over 10 years of experience researching and writing on Chinese economic development, he works with ESAI's domestic and international clients on Chinese and Asian petroleum market analysis. He is the principle author of ESAI's recent multiclient study, Fueling China: Oil and Gas Demand to 2010. Pietz holds a PhD in Chinese economic history from Washington University and is also an Associate in Research at Harvard University's Fairbank Center for East Asian Research.