US Northeast has cause for concern over heating oil supply but no cause for panic

Low inventories, memories of last January's cold snap, tight supplies of natural gas, and renewed threats to stability in the Middle East have all contributed to new worries about US heating oil supplies for the coming winter.

These concerns have created pressures for government action at the federal, state, and local level. Some measures have already been taken: the creation of a Northeast Heating Oil Reserve, the recent offer of 30 million bbl of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and new requirements imposed by New York and New Jersey that large, interruptible-gas customers hold 7-10 days of alternative supply.1 Others have been proposed, including a ban on distillate exports.

This article reviews the key influences on the heating oil supply-demand balance for the coming winter, especially in the US Northeast. The report also looks at the effects of current and proposed government actions.

Higher costs for heating homes this winter are almost inevitable. Last winter was unusually warm, except for the exceptional late-January cold snap, holding down seasonal fuel needs.

Crude oil prices currently are about $10/bbl, or 24¢/gal, above year-earlier levels, while natural gas prices at the wellhead are up about $2.50/Mcf, or about 36¢/gal of heating oil equivalent.

Certainly, low distillate inventories are cause for concern. However, production of distillate is up strongly, especially production of high-sulfur distillate. Indeed, refinery runs for the past 6 weeks have been at record levels.

Moreover, there is some evidence that secondary inventories are building. Barring an oil supply disruption or cold weather, world oil market conditions are likely to stabilize, gradually improving prospects of meeting winter needs.

But consumers will pay more to heat their homes this winter, nevertheless, as they will almost certainly need more fuel, and prices will be higher.

Government actions

Actions by the US government to date are having a decidedly mixed influence. The release of SPR oil is clearly adding to the world supply of crude-although not necessarily to net US supply-and to the distillate supply potentially available to US consumers, whether refined at home or abroad.2

But timing is everything, and other government actions couldn't have come at a worse time. The filling of the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve, added to already intense competition for supply, placed further pressure on prices, exacerbating backwardation and creating a disincentive to build commercial stocks.3

Moreover, concerns about which circumstances will trigger use of the reserve have the potential to interfere with the country's critical winter supply safety valve-increased product imports. New York and New Jersey requirements for holding alternate fuels (issued in mid-August and mid-September, respectively) also aggravated price pressures, because the stocks had to be in place by Oct. 1 in New York and Nov. 1 in New Jersey.

Because the US is a net importer of distillate, proposals to interfere with product trade by imposing a ban on exports would be particularly misguided, especially in the winter months when product is most needed.

There are actions that clearly could be helpful. Currently, no additional Jones Act (US flag) ships are available to move oil from Gulf of Mexico refineries to the US East Coast,4 and pipelines are full. A temporary waiver of the Jones Act requirement would allow movement of local distillate supplies to the Northeast rather than out of the US, although this could cause some offsetting displacement of imports.

The US Environmental Protection Agency could cooperate with state and local planning to temporarily allow adjustments to product specifications, a clear step towards improving potential supply. The government also could help by collecting and providing clear information on what is a "black hole"-namely, the state of secondary and tertiary inventories.

Keep in mind that developments in the Middle East and their potential for global oil supply disruption add a new dimension of risk. It was precisely to meet such a threat that the US and other major consuming countries established strategic reserves. The US and other governments should make it clear that such reserves would be used in the event of a disruption to world oil supplies. While there has been controversy over the appropriateness of the recent SPR release, there would be none in the case of a clear supply disruption.

Price trends

Given the trends in oil and gas prices, consumers of both fuels are facing significantly higher costs at the beginning of this winter heating season vs. a year earlier. Fig. 1 shows trends in crude oil and distillate prices in the left panel and trends in natural gas prices in the right panel from early 1998 through mid-October of this year.

For Oct. 20, the price of West Texas Intermediate was averaging about 78¢/gal (nearly $33/bbl), up about 24¢ from its price a year ago and about 50¢ above its low point in December 1998.

The rise in crude oil prices would be expected to flow through, more or less, to product prices. For most of the period shown, spot distillate prices in the Northeast, the most critical heating oil region as measured by the New York Harbor price of No. 2 oil, have moved in line with WTI, with an average price differential of about 6¢/gal.

There have been two sharp breaks with this pattern-in January 2000, when the monthly average differential reached 20¢/gal (with a daily peak differential of 50¢ reached on Feb. 3-4) and in October, when the average differential was again at about the 20¢ level.

There is a major difference, however, between conditions in January and conditions now. As shown at the bottom left of Fig. 1, in January there were sharply wider differentials between New York Harbor distillate and WTI and between distillate in New York Harbor and distillate on the Gulf Coast.

In effect, the January spike reflected an extraordinarily tight market in the Northeast rather than a national problem. In contrast, the New York-Gulf Coast differential in October was averaging only 3¢/gal, indicating that the price pressures at this point are not confined to a single region.

The right panel on Fig. 1 shows prices for gas at the New York city gate (as indicated by Transco Zone 6 prices) and at Henry Hub. In mid-October, both sets of gas prices were up by about $2.50/Mcf, or about 35¢/gal of heating oil equivalent-only slightly less than the 39¢/gal increase in New York Harbor distillate for the same period.

As with distillate, an extraordinary price differential opened up between gas delivered to New York and to Henry Hub earlier this year. In January, the average differential reached nearly $4/Mcf. The January average price itself reached $6.30/Mcf, or nearly 90¢/gal of heating oil equivalent.5 The Oct. 20 differential between the New York and Henry Hub price was about 42¢/Mcf, in line with the average differential prevailing during 1998-2000, indicating that gas as well as distillate price pressures are national in scope.

With Northeast spot distillate prices at the very beginning of the winter heating oil season already running well above their January average, there are obvious reasons for worry about possibilities of new price run-ups ahead. The next sections focus on aspects of the physical market that could reinforce, or dampen, these concerns.

US distillate inventories

Worries about distillate supply tend to focus immediately on the current, very low level of inventories, especially inventories of high-sulfur (greater than 0.05% sulfur) distillate used for heating oil. Industry inventories of low and high-sulfur distillate since yearend January 1999 are shown in Fig.2. Figures are shown for the US as a whole and for Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) I, the East Coast, where most heating oil is used.

At the national level, industry inventories as of Oct. 20 had risen to 112 million bbl from their end-of-March 2000 low point. But this is 28 million bbl less than a year ago, with the high-sulfur distillate used for heating oil-24 million bbl-responsible for most of the decline.

Because inventories are typically drawn down to meet seasonal demands in the fourth and (especially) first quarters of the year, this exceptionally low starting point raises questions about supply adequacy, especially if colder-than-normal weather puts pressure on both normal heating oil customers and interruptible gas customers.

The inventory situation looks even more worrisome in PADD I, because nearly all the reduction in stocks has taken place there. Industry inventories there are down by 27.5 million bbl, or about 41% vs. a year ago, while high-sulfur distillate stocks are down 23 million bbl, or 49%.

High-sulfur stocks in PADD I are important, accounting for 70% of that area's total stocks in 1999 vs. 32% for the rest of the country. The Northeast Heating Oil Reserve is adding 2 million bbl to this total, or less than 10% of the shortfall in PADD I stocks vs. last year.6

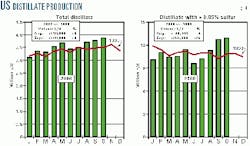

Distillate production

Low distillate inventories are part of a broader problem. Total US industry stocks of crude oil and products, shown in Fig. 3, are low, currently 75 million bbl below year-earlier levels. The rate of inventory rebuilding from the February low point has been slow, with no apparent overall recovery over the summer months. Nonetheless, the decline in distillate stands out, down 20% on its year-earlier level vs. reductions of 4% for gasoline and 5% for crude.

One reason for the difference between distillate stocks and the other categories is that, in the spring and early summer, refiners had another, more immediate priority, gasoline. However, that has changed, and distillate production has moved up substantially over the past several weeks

As shown in the left panel of Fig. 4, beginning in August, total distillate production has been running significantly above 1999 levels and, overall, at record volumes. Total production was up over 300,000 b/d in August and September vs. the year before, a gain of 9%.

As shown in the right panel, production of high-sulfur distillate was up by 255,000 b/d in September, an increase of 25% over September 1999. Production data for the 4 weeks through mid-October indicate that production continues to run well ahead of last year's levels.

The recent production trends are improving the odds of avoiding a winter supply problem. So far, they have not translated into a significant build in overall primary distillate inventories, although there has been a gain in high-sulfur stocks.

Total distillate stocks as of Oct. 20 were about the same as end-of-July stocks. High-sulfur stocks, however, have moved up by 4.5 million bbl (plus the 2 million bbl placed in the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve) or by about 45% of the increased production since July (65% including the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve).

Still, given the absence of heating oil demand in August-September and negative secular trends in heating oil use, why didn't more go into stock-building? This may in fact be happening, but the official statistics would not capture increases in secondary and tertiary stocks.

Official government statistics record product stocks held by major industry participants-refineries, pipelines, and terminals-but not by end-users. Earlier-than-normal fill-ups of end-user heating oil tanks show up as higher demand rather than higher stocks. While no data exist, various press reports indicate that this is, in fact, happening as consumers of oil (and interruptible natural gas) react to reports of potential supply problems and price spikes this winter. Interruptible and spot gas customers forced into the distillate market last winter are also likely to be building stocks, even apart from those required to do so this year in New York and New Jersey.

The Northeast Heating Oil Reserve fill is already complete, and when stock-building by end-users subsides, a greater share of available supply will move into officially recorded primary commercial inventories.

Distillate trade

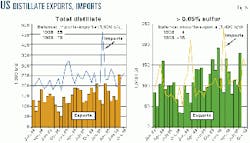

To this point, the analysis has ignored the role of distillate trade, imports, and exports in the US supply-demand balance. Although modest on a net basis, trade does play a critical role in meeting winter peak demands.

Fig. 5 summarizes recent trends in total distillate exports and imports, specifically high-sulfur distillate. Overall, the US is a net importer of distillate. In 1998-99, imports exceeded exports by about 85,000 b/d.

There is a seasonal aspect to the trade, with imports tending to peak in the winter months. In February of this year, imports reached an extreme peak of 460,000 b/d, about 140,000 b/d above the February 1999 level as the market responded to the late-January spike in Northeast distillate prices.7

Seasonal patterns are more striking in the case of high-sulfur distillate. On a year-average basis, exports and imports of high-sulfur distillate are almost in balance, but in peak winter months imports move up sharply, while exports fall back.

This summer shows a significant increase in imports relative to 1999. For July-September, imports of high-sulfur distillate were averaging about 36,000 b/d above 1999 levels, nearly a 40% increase. For the 4 weeks ended Oct. 20, imports of high-sulfur distillate were up 66,000 b/d, or nearly double the level a year ago.8

Export figures for August, the latest month available, show an unusual surge, with total distillate exports up about 120,000 b/d vs. July and high-sulfur distillate accounting for nearly 80,000 b/d. As a result, the US was a net exporter in that month, encouraging proposals to impose curbs on exports.

However, over half of the August increase in distillate exports went to one country, Mexico, which is a partner in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Mexico also is a major supplier of crude to the US and, as shown in the next section, was the largest single market for US distillate exports last year.9

Although the export data to confirm it are not yet available, the sharp rise in distillate imports since August almost certainly means that the US has returned to a net import position.

Industry logistics and regulation greatly influence the distillate trade-and all oil trade, for that matter. The bulk of US refining capability is in the Gulf Coast, while the greatest need for heating oil is in the Northeast. Much of gulf distillate production moves by pipeline to other parts of the country. The remainder must move by ship. The Caribbean and Central and South America are natural outlets. The Northeast US is another, of course, although here there is a complication. Under the Jones Act, shipments between US ports must be made on US flag ships, which are generally more expensive than international flag carriers. The Jones Act, therefore, increases both the attractiveness of exports relative to US trade (from the supplier's viewpoint) and the attractiveness of imports relative to US sources (from the US customer's viewpoint).

The extent of any distorting influence in favor of international over US trade is modest under most circumstances. The distortion is greater right now, when refinery output is increasing while Jones Act shipping capacity is limited. In this context, proposals to limit distillate exports are unlikely to have the intended effect of increasing supplies to East Coast customers.

Without a waiver of the Jones Act, US production under an export ban would be reduced. Current expanded production would have difficulty finding a US outlet. With the export option not available to absorb it, refiners would be forced to cut back.

At the same time, international customers deprived of their US supplies would enter the market to bid away imports currently moving to US customers. We would, in any case, be disrupting long-term trade relationships, primarily with our neighbors, and possibly inviting retaliation.

US exports, imports

Fig. 6 shows the distribution of US distillate exports and imports in 1999.

Exports totaled 162,000 b/d, of which nearly 70% went to Mexico, Canada, and other Western Hemisphere locations. A small volume, about 6,000 b/d, went to Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands are treated as international locations in official trade statistics. Exports to Singapore accounted for 14% of the total and exports to Western Europe, 8%.

Imports amounted to 250,000 b/d, with 83% coming from Canada, the US Virgin Islands, and Venezuela. Canada's prominent role in the distillate trade is consistent with the long-standing integration of the US and Canadian economies, particularly regarding energy. Canada, Mexico, and the US are all members of NAFTA, an agreement made with the explicit aim of expanding free movement of goods, services, and capital flows among its members. Export restrictions against these two countries would prove particularly sensitive.

A global perspective

The low state of US inventories is part of a wider global condition. In March 1998, OPEC countries (along with certain other major producers) agreed to a significant cut in production-the first of three major cuts over the next year totaling more than 4 million b/d-in order to promote a recovery in oil prices from their exceptionally depressed levels. The cutbacks lowered the world oil supply at a time of growing demand, forced drawdowns of worldwide inventories, and pushed up prices by far more than was originally anticipated.

As shown in Fig. 7, OPEC crude production fell to a low of 25 million b/d at the end of the year from about 28 million b/d in early 1999. With non-OPEC production almost flat, this cut translated, virtually barrel for barrel, into lower world supplies. The trend in commercial stocks of crude and product in the three major consuming regions indicates the impact on world inventories. Total stocks fell by nearly 300 million bbl from the beginning of 1999 to the beginning of this year.

In March, June, and again in September 2000, OPEC agreed to a series of production increases that favor a significant easing of oil market conditions, although not right away. As of September, OPEC production was running 4 million b/d above its low point at the end of 1999 and is still moving up. There are already signs of a modest rebuilding of global stocks.

Barring an oil supply disruption, the US should find increasing scope in the world market for distillate supplies to meet any reasonable shortfall in winter requirements. There is, however, a question about the impact of the newly created Northeast Heating Oil Reserve on incentives to do so.

Heating oil reserve impact

Establishment of the 2 million bbl Northeast Heating Oil Reserve was meant to reassure consumers in that region that they are protected against a new winter supply problem and price spike. But this volume is not really that large. It amounts to less than one third of the 7 million bbl of high-sulfur distillate imported into the US in February of this year-and less than three days of total distillate imports during the peak week ending Feb. 21.

Moreover, while establishment of the reserve was well-intended, its existence creates a new uncertainty: Under just what conditions will the reserve be used? These concerns distort the risk-reward calculations of market participants and inhibit an import response to future supply problems. Now, in addition to market risk, suppliers must factor in a new risk-the government.

Anyone contemplating bringing in more imports in response to a tight market would have to consider whether a potential release of the oil would drive down the price to the point that the arriving imports would have to be sold at a loss.

In effect, speculation regarding the conditions of any release could potentially put at risk as much distillate as there is in the reserve, or even more. The reserve could be forced into the role of supplier of first, rather than last, resort, and it is simply too small to fulfill that role. The more aggressive the potential use of the government reserve, the greater the skewing of price risk towards the downside and the greater the disincentive of the private sector to hold inventories.10

References

- A heating oil supplier can hold these stocks offsite on behalf of the gas user. Thus, ironically, interruptible gas users could have preferential access to heating oil inventories during a supply disruption.

- The US Department of Energy estimates that 30 million bbl of the release will increase net US crude supply by 10 million bbl, with 20 million bbl backing out imports.

- In the case of crude markets, the government has been more sensitive to timing concerns and the need to keep supplies in commercial hands. The government has repeatedly postponed the taking of royalty in-kind crude oil but has not applied the same logic to the Northeast Heating Oil Reserve.

- With rates so high, owners of all eligible US flag vessels should have made them available.

- The daily price peaked on Jan. 26 at $11.08/Mcf, or $1.53/gal of heating oil equivalent.

- Natural gas stocks are also low. As of mid-October, the volume of working gas in storage in the US East was down 7% from its year-earlier level. This is somewhat better than the national average, where overall working gas in storage is down 14% from its year-earlier level.

- The response of imports to higher prices this past winter is even sharper when weekly statistics are considered. In the last 2 weeks of January, distillate imports averaged about 150,000 b/d. Imports reached 528,000 b/d for the week ended Feb. 11 and a peak of 718,000 b/d for the week ended Feb. 21.

- The latest import figures shown are 4-week averages for the week ended Oct. 20. The figures (not shown) for the latest week are more spectacular. Total distillate imports surged to 445,000 b/d, while imports of high sulfur distillate reached 149,000 b/d.

- The Mexican national oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos, has made investments in the US refinery sector, notably its half-interest in the Deer Park, Tex., refinery, as part of its effort to meet product demand.

- The recent change of 30 million bbl from the SPR, coupled with a "price" trigger for the product reserve, increases the odds that politics and price will strongly affect when and whether the product reserve is triggered.

The authors

Ronald B. Gold is a consulting senior adviser to PIRA Energy Group and a consulting vice-president of Petroleum Industry Research Foundation Inc. (PIRINC), New York. He retired from Exxon Corp. at yearend 1997, where he was company economist and manager of the Energy Outlook division for Exxon Co. International. Gold also has worked for the US Treasury Department, Office of Tax Analysis, and was an assistant professor of economics at Ohio State University. Gold has an undergraduate degree from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, and an MA and PhD in economics from Princeton University.

Larry Goldstein is president of PIRA Energy Group and president and a member of the board of PIRINC). He has been a member of the Petroleum Advisory Committee of the New York Mercan- tile Exchange and a contributor to studies by the National Petroleum Council. He served as a board member and treasurer of the Scientists Institute for Public Information.

John H. Lichtblau is chairman and CEO of PIRINC. He headed PIRINC as executive director during 1961-1990. He has served since 1968 on the National Petroleum Council, an industry advisory group appointed by the Secretary of Energy, and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Lichtblau also is chairman of PIRA Energy Group, a private consulting firm. A leading international expert on the petroleum industry and petroleum economics, he has authored a number of publications, has been a frequent witness at congressional hearings on energy policy, and a keynote speaker and lecturer at conferences and seminars. Lichtblau performed his undergraduate work at the City College of New York and graduate study at New York University.