Tyumen Oil adopts Western-style management

Wading through the aftermath of the recent economic collapse in Russia continues to be an uphill battle. Some Russian oil firms, however, have achieved reasonable success in navigating the swells of turbulent economic seas, especially in a country that relies so heavily on petroleum revenues. These firms' survival stories contain similar threads, not the least of which is the formation of partnerships with Western firms to revive an ailing-and traditionally ill-managed-oil industry in Russia.

Simon Kukes, president and CEO of integrated Russian oil company Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK), says a number of Russian firms, like his own, are reaching financial stability again through a four-step evolutionary process involving 1) survival, 2) modernization, 3) domestic consolidation, and 4) internationalization.

Kukes says that TNK has fared well through the economic turbulence due largely to the continued strengthening of its alliances with Western oil firms. Now 100% privately owned, TNK has been working with several Western engineering firms, such as Halliburton Co. unit Halliburton Energy Services, to optimize production from its oil fields in western Siberia.

Survival, modernization

In times of crisis, simply surviving is the first step on the road to financial stability, Kukes explains. When TNK was created, it had a tremendous responsibility in what Kukes calls the "social spheres." At that time, TNK's owners inherited certain regional activities well outside the traditional responsibility of an oil company, including financial support for schools, hospitals, hotels, and construction businesses. In order to survive, TNK has found itself having to sever ties with these noncore activities.

"During this period," said Kukes, "we really had to cut the social spheres out of the picture. Our company reduced its workforce by 40%. Within a year and a half, we practically got rid of everything."

Following such divestment measures, many Russian oil firms, TNK included, are placed in a positive cost position, says Kukes. TNK essentially centralized its operations to minimize-if not eliminate-any losses. Also during this period, TNK attempted to decrease its dependence on contracts with the government.

The next step, modernization-a level where TNK and many other Russian firms stand today-is reached through the introduction of modern management practices and updated technology. Many Russian firms continue to approach this phase of development from different angles, Kukes says. For TNK, this step involves both its upstream and downstream sectors.

Downstream, one of TNK's main thrusts has been to position itself at the forefront of the Russian domestic retail market. In Moscow, for example, it is TNK's goal to increase its market share to 20% from the current 5% by 2002.

"Under the Soviet regime, the concept of a retail market did not exist-customer service was not part of the mindset," said Kukes. "So, in today's conditions, the retail sector has tremendous growth potential.

"Vehicle ownership is rising, and gasoline demand keeps on going up, even in periods of economic hardship," he continues, "In addition, Russian customers have shown that they too-just like customers everywhere-are attracted by modern facilities and good service." Kukes predicts an increase in progress in this portion of the industry over the next 2 years.

"We are gearing ourselves up to the retail trade in Central Russia," said Kukes. "We also want to expand to Ukraine and even to Belarus perhaps, but for that, we need processing capacity, and we intend to increase this capacity in Central Russia." Kukes says the current situation in the Ukraine-high demand, low competition-is the ideal condition for expansion. "Going downstream anywhere else," he said, "we would have to be careful," given Russia's lack of marketing experience.

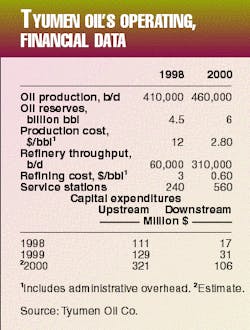

Also receiving top billing as part of TNK's downstream modernization scheme is the continuing revamp under way at its Ryazanskii refinery. "The Ryazan plant has become the producer of the best lead-free, high-octane fuel in Russia over the last few years," said Kukes. The plant's capacity has grown to 310,000 b/d (see table). TNK gets the highest profits it can attain through the export of refined products.

Said to be in one of the best locations in central Russia, the Ryazan refinery provides TNK with an edge over its competitors, say many analysts, as it supplies most of the central Russian regions. Analysts say the Ryazan plant is one of the few in Russia that produces fuel according to stringent European standards.

Dmitry Avdeyev, an analyst with United Financial Group, said crude oil binds a producer to world prices, but refined products offer freedom to decide the price. "When you supply your oil to a middleman, you automatically lose a huge profit from the difference between the market price of the oil from the plant and the end price at the filling station," Avdeyev said.

Kukes said, "TNK and other large oil companies will therefore start their own filling stations. The profitability of this approach has already been proven by Lukoil. BP [Amoco PLC], for example, is increasing its filling station network in Moscow, but we are expanding our network under our own trademark."

TNK plans to double the number of outlets in its retail station network before 2002. In August, an agreement was signed with the Canadian firm West Group Resources for the supply of $29 million worth of filling station equipment, $5 million worth of which was to be received before the end of 1999.

Consolidation and beyond

The third step to regaining economic strength-the consolidation of Russia's companies-has already started, notes Kukes. And although there are no successful examples of any major mergers of Russian oil firms, Kukes said, "There were several big acquisitions in 1999, some friendly, some hostile, just as in the West," citing examples in Lukoil's purchase of Komitek and TNK's acquisition of troubled Sidanko unit Kondpetroleum.

In addition, global merger activity will continue to put pressure on Russia, Kukes says. "I expect mergers, acquisitions, and joint ventures in Russia to pick up in the third quarter of 2000 and to peak in 2001," he said. Russian firms will either begin to merge their assets or merge certain parts of their companies through the formation of joint ventures, he says. And, as for TNK, says Kukes, if it is to increase its production to acceptable levels-to more than 800,000 b/d-in the coming years, it would do so mainly through merger activities, most likely several.

Internationalization is the final step that Russian companies such as TNK will take. From both geographical and financial points of view, says Kukes, there is too much risk associated with concentrating production in one region, such as TNK's focus in Western Siberia. At the same time, says Kukes, TNK's experience in operating in Russia can be shared with other oil companies to assist them in taking full advantage of the assets.

This internationalization should be- gin by yearend, Kukes says, and will help place some Russian companies into "the major leagues." Before it can take full root, however, improvements will need to be made in Russia's tax system, production-sharing agreement guidelines, and the general stability of the political landscape.

"I am not suggesting that all of the Russian companies will have 'gone international' over the next 2 years. We are probably talking of a 3 to 5-year time frame. But I am sure of this: As this transformation occurs, we will see the development of a stronger and more successful oil industry in Russia," said Kukes.

TNK's past, present

TNK is a new company, even by Russian standards. It was formed in 1995 by a government decree granting it 38% stakes in nine existing companies. But despite its short history, the company has made its mark in the industry, developing into one of the most aggressive Russian oil firms-even winning a bitter battle against BP Amoco over control of Chernogorneft, a key subsidiary of Sidanco, in which BP Amoco holds a major share.

(Chernogorneft was sold to TNK over the objections of BP Amoco, which threatened to pull out of Russia over the sale of the unit [OGJ, Jan. 3, 2000, p. 26]. In the end, TNK made peace with BP Amoco, agreeing to return Cherno- gorneft to Sidanco in a complicated deal that left TNK with a 25%-plus-one-share stake in Sidanco, according to company officials.)

Until 1997, the government continued to be a majority shareholder in TNK, with an 89.87% holding. But in June 1997, a 40% stake was sold to Novyi Holding, leaving the state with 49.87%. Then, in early 1998, Alfa Group-the founders of Novyi Holding-and American-Russian Access Industries/Renova bought a 9% stake from private shareholders and 1% at a special auction, leaving effective control of the company in the hands of Alfa Group, which includes Alfa Bank and oil trading company Alfa Ekho.

(Unconfirmed reports speculate that Alfa is in talks to divest its holdings in TNK as part of a portfolio-pruning program.)

"Even 18 months ago," said Steven Dashevski, analyst with the ATON brokerage firm, "bearing in mind that TNK was formed in 1995 by an order from above, and they had enough problems already, the management had to fight desperately to consolidate its assets. But they managed to sort out the growth problems quickly, and now it is one of the strongest and most effective structures in the fuel and energy complex."

Since the beginning of 1998, TNK's management has been restructuring the company and is now busy clearing its debts, both with private investors and the state. During 1997-99, TNK repaid debts of 1.44 billion rubles, which included 900 million to the federal budget.

"We have entirely restructured and almost paid off all federal debts and pensions," Kukes said, "In the next 2-3 months, the company will throw off all its debts."

TNK's leadership has been another driving force behind its movement toward Westernized thinking. To date, its corporate management team has grown to include several US citizens, including Kukes.

In 1998, Kukes was named one of Central Europe's 10 leading managers by the Central European Economic Review magazine. The recent recognition of his work in the development of the company led to TNK being awarded an internal credit rating of 44 by the EA Ratings agency (a partner of Standard & Poor's), the highest of any Russian securities issuer.

Appointed earlier this month to the position of vice-president for strategic and capital planning, upstream operations, Jeffrey B. Karfunkle also is a US citizen. He will be working to establish and maintain contacts with Western engineering and services companies to further whittle production costs and introduce the most efficient technologies into the company's oil fields, says TNK.

It is through such additions to its management, says Kukes, that TNK is able to continue taking steps towards "institutionalizing the implementation of Western practices."

Simon KukesI am not suggesting that all of the Russian companies will have 'gone international' over the next 2 years. We are probably talking of a 3 to 5-year time frame. But I am sure of this: as this transformation occurs, we will see the development of a stronger and more successful oil industry in Russia. Photo by Mikhail Dychliuk.

Tyumen Oil Co.

President and CEO