Bangladesh natural gas exports to India: LNG alternative with narrow window

This article is part of a special report, India's LNG Prospects, that begins on p. 62.

With all the attention focused on India's forthcoming LNG boom, it is worth noting that there is a less-costly alternative right next door: pipeline imports of natural gas from Bangladesh.

However, the window for that alternative is very narrow and closing rapidly.

At its current rate of production, Bangladesh has enough natural gas reserves to meet its consumption needs for the next 38 years. Under our high-case natural gas consumption scenario, Bangladesh would still have a minimum of 137.1 billion cu m (bcm) of reserves in 2010, excluding exports. We estimate that Bangladesh can easily meet the requirements of India's gas needs in West Bengal and, if necessary, New Delhi. These two locations have the most potential due to their proximity to Bangladesh.

Initial potential natural gas demand in West Bengal is estimated at 3-4 bcm/year, whereas New Delhi can take as much as 12.4 bcm/year. Bangladesh could earn anywhere from $300 million/year to $1.7 billion/year initially by exporting natural gas to India. The money would bring in much needed foreign capital to Bangladesh and could offset up to 70% of the country's current trade deficit.

Pipeline gas from Bangladesh will cost less than LNG imports. Pipeline natural gas imports from Bangladesh to New Delhi are $0.55-$0.75/MMbtu less than LNG imports, a potential saving of $400 million/year for India.

We believe that natural gas exports to India from Bangladesh will foster stability and improve relations between the two South Asian countries. Bangladeshi natural gas exports to India will benefit both countries economically and politically.

Bangladesh supply

While the Bangladeshi government is aware of the country's high reserves-to-production ratio and the huge potential reserves that foreign companies believe exist, the government still refuses to permit any natural gas to be exported to India by pipeline.

The foreign companies are willing to continue to spend capital to explore, however, provided they can export part of the country's large reserves. India would be the primary buyer and, logically, India would be willing to pay for the less expensive piped gas over the more costly LNG.

While no current infrastructure to export Bangladeshi natural gas to India exists, the country's proximity to India offers a potential advantage over other suppliers. Currently foreign companies hesitate to invest because the government insists that the natural gas not leave the country. The government is afraid of not having enough supply for itself. Meanwhile, the opposition in Bangladesh frequently accuses its government of selling out to India. If the Bangladeshi government understood that it has a lasting surplus of natural gas, then exporting part of this surplus could earn the country much-needed foreign capital.

It becomes critical, therefore, to investigate the future balance of Bangladesh's natural gas supplies and the potential earnings from them. Consequently, it is important to also discuss the benefits India would receive through Bangladeshi natural gas imports, stressing how both sides can win from the proposition.

Bangladesh demand

In 1998, Bangladesh consumed 7.8 bcm of natural gas. In the same period, Bangladesh's commercial primary energy consumption (i.e., excluding biomass consumption) was 70% natural gas, 29% oil, and 1% hydroelectric. Fuel consumption in electricity generation was 87.1% natural gas, 6.5% oil, and 6.4% hydro. Both statistics clearly show that Bangladesh's economy depends primarily on natural gas for energy.

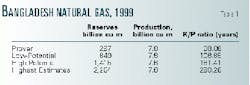

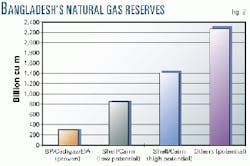

Bangladesh's current proven reserves for natural gas are 297 bcm. Foreign investors, however, believe that the potential reserves are significantly higher, although their estimates differ (Table 1, Fig. 2). Royal Dutch/Shell and Cairn Energy PLC estimates range from 849 bcm to 1,415 bcm, while some other companies have speculated as high as 2,264 bcm. No one can be certain of how large the potential reserves will turn out to be, but previous experience has shown that potential reserves often become proven reserves over time.

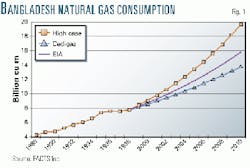

From 1988 to 1998, the average annual growth rate (AAGR) of Bangladesh's natural gas consumption was just over 6% (Fig. 1). Fig. 1 also shows three scenarios of Bangladeshi natural gas consumption growth to 2010. Cedigaz, a well-known gas-related French research institution, forecasts a 4.9% AAGR, whereas the US Energy Information Administration provided a scenario of 6% AAGR. We add a high-case scenario of 8% AAGR. This high case predicts an increase of 11.8-19.6 bcm in 2010, still leaving Bangladesh with a 1999 level of proven reserves at 137.1 bcm. Potential reserves are much higher.

Because all of Bangladesh's natural gas is consumed domestically and because the country imports no natural gas, the consumption figures (including losses) are similar to the production figures. Table 1 shows the reserves to production (R/P) ratio based on the 1998 level of production. The absolute minimum R/P ratio is 38 years, which is considered by most to be plentiful enough to allow for some exports. Attesting to the belief that the reserves will increase in the future is the desire of foreign companies to explore for more natural gas, especially when they seem convinced that much more exists.

Table 2 shows the R/P ratio in 2010 calculated for the high-case scenario of 8% AAGR. This leaves production in 2010 at 19.64 bcm. The cumulative amount of natural gas predicted to be produced and consumed from 1999 to 2010 at an 8% AAGR is 137.14 bcm. To determine the reserve levels for 2010, 137.14 bcm was subtracted from the 1999 reserve levels used in Table 1.

If we assume the high-case AAGR of 8% and no new reserves are found within the next 10 years, then Bangladesh has only 7 years of production left in 2010. Considering the potential of Bangladesh's natural gas fields, however, this is highly unlikely when compared with the average annual increases in reserves around the world. Assuming a modest 5% AAGR in reserves over the next 10 years raises the R/P ratio to almost 25 years, which is high enough to permit natural gas exports to India, if nowhere else. The Shell-Cairn low-case scenario of potential reserves is 35 years, also indicating a surplus large enough to allow regional natural gas exports. Keep in mind that all of the R/P ratios are based on the high-case scenario for consumption and production AAGRs for natural gas. The more-moderate AAGRs make natural gas exports even more affordable.

India: an export target

Despite the Asian economic crisis, India's GDP growth was still strong in 1999. Accompanying the economic growth, increases in power generation capacity is and will continue to be important to this developing country, whose population has surpassed 1 billion people.

It is obvious that, to meet its future energy needs, India will have to rely on outside sources. India is already a major importer of oil and is on the brink of importing natural gas in the form of LNG. The indigenous gas fields in India are primarily located in Western India, which is relatively far from the markets in New Delhi and West Bengal. Thus, considering that an abundant supply exists in neighboring Bangladesh, building the transport infrastructure from Bangladesh would be both closer and more convenient than LNG imports or domestic sources.

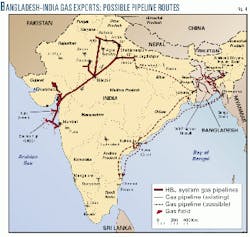

The markets that can utilize natural gas imports from Bangladesh are near New Delhi and West Bengal. A pipeline to New Delhi from Bangladesh via Calcutta would extend about 3,070 km. Few have discussed such a pipeline, due to India's interest in LNG and Bangladesh's vocal opposition to exporting its natural gas.

While a plan for an LNG terminal relatively near West Bengal exists (Paradeep, 340 km southwest of Calcutta), it is still farther and will likely be more costly than any pipeline extending from Bangladesh to Calcutta. The proposed LNG terminal at Paradeep has nearly been forgotten over the last year, and the plan mentioned nothing about supplying power or regasified natural gas to West Bengal.

A coastal pipeline from Chittagong in Southeast Bangladesh to Calcutta would extend 370 km. Alternative supply sources are LNG imports from Malaysia (about 2,400 km), Indonesia (about 3,700 km), or from Qatar (about 6,000 km). As for the LNG that has been slated for delivery or is in the process of being slated, its destinations and uses have already been determined.

Revenue from gas exports

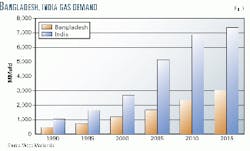

Industry sources calculate an initial potential demand of 33.96 million cu m/day (MMcmd) in New Delhi. In West Bengal, the area south of Calcutta is expected to consume 8.49-11.32 MMcmd. If the gas were not immediately available, India would use naphtha to run power plants, as it will do at the Dabhol power plant in the state of Maharashtra until the LNG terminal there is completed. The above rates result in an annual consumption of 12.4 bcm for New Delhi and 3.1-4.1 bcm for West Bengal.

Piped gas to New Delhi is estimated to cost $2.80-3.00/MMbtu and to West Bengal, $2.60-2.70/MMbtu. Table 3 shows Bangladesh's potential export revenues at such prices.

The aforementioned reserve estimates show that Bangladesh can easily accommodate natural gas exports to West Bengal even if no new reserves are ever discovered. The reserve estimates also show that, if any of the potential estimates are correct, then Bangladesh can easily accommodate natural gas exports to New Delhi. Exporting only to West Bengal will earn $300-400 million/year, and adding New Delhi will increase export revenues to around $1.2 billion/year. These figures only calculate the initial use of natural gas in those areas. Anticipated growth in the consumption of these regions and the expansion of pipelines to other nongas-receiving areas of India will further increase Bangladesh's export potential.

Win-win solution

In 1998, Bangladesh exported $5.1 billion worth of merchandise, with a $2.4 billion trade deficit. Exporting natural gas to India will increase export revenues by a minimum of $300 million/year to a maximum of $1.7 billion/year initially. The increase in revenues could reduce the trade deficit to at least $2.1 billion/year, with the potential to have a trade deficit of only $700 million/year.

If the Bangladeshi government or its opposition were to campaign against the other by arguing that one is denying Bangladesh its due economic growth, then they would likely win support for exporting natural gas to India. A good public relations campaign could show not only how big the reserves are but also how the exports could help raise Bangladesh's standard of living. If the campaign successfully explained how the money could be used to further Bangladeshi development, then it would be difficult for politicians to refuse to support natural gas exports to India. Exporting natural gas to India could even be viewed domestically as an assertion of Bangladesh's power over India.

As for India, from an economic point of view, it would clearly prefer to have access to less-expensive pipeline natural gas. LNG costs a minimum of $2.50/MMbtu to bring it to port, $0.70/MMbtu to regasify it, and another $0.25-0.35/MMbtu to bring it to New Delhi; the total would be $3.45-3.55/MMbtu at the city gate (of New Delhi). The LNG price is substantially greater than the above natural gas price from Bangladesh to New Delhi of $2.80-3.00/MMbtu, a potential savings of up to $400 million/year.

In addition to natural gas being discounted to New Delhi by $0.55-$0.75/MMbtu over LNG, Bangladeshi natural gas exports have some less tangible, though important, benefits. The exports will require the governments of Bangladesh and India to cooperate. Such cooperation would be long-term, because it involves building and maintaining a pipeline. The relationship would foster stability between the two countries and set a precedent for future cooperation.

While it is much less expensive for India to buy natural gas from Bangladesh than to import LNG, it is much more expensive for Bangladesh to retain its natural gas than to export it to India. India, however, will not waste time waiting. The country may seek to supply its markets in New Delhi and West Bengal by other means. If Bangladesh waits until its government or Petrobangla (the Bangladesh state oil and gas company) proves how big the reserves are, then it may be too late. India will have found other ways to meet its energy needs, and Bangladesh will realize the magnitude of the potential cash cow it has ignored. With the rest of the world doing everything it can to get into the Indian market, it seems a bit shortsighted for Bangladeshi politicians to ignore it because of political prejudices. Both countries have much to gain if they act quickly.

The Author

Fereidun Fesharaki is the president and founder of Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services (FACTS Inc.). Born in Iran, he received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran. He joined the East-West Center in 1979 and currently is a senior fellow and head of the Energy Project at the East-West Center. His area of specialization is oil and gas market analysis and the downstream petroleum sector, with special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region, Middle East, Latin America, and US. He is an adviser to numerous oil and gas and other energy companies, private and state-owned, and governments in the Middle East, Pacific Basin, and Latin America, as well as the US government.