A veteran revisits Iraq’s oil resource and lists implications of the magnitude

Tariq Shafiq

Petrolog & Associates

London

Iraq’s oil reserves, revised to 143.5 billion bbl in late 2010 from the 115 billion bbl official figure that held for several years, will no doubt turn out to be much larger than the late-2010 estimate.

The Iraq Ministry of Oil also announced an estimate of potential reserves of 215 billion bbl.

In the nationalized decades leading up to the 1990s, 155 wells were drilled on 113 structures, many of which are 10 km long. Even structures that produced oil were not sufficiently investigated. The concept of what was commercial was influenced by oil priced at $1-3/bbl and conservative recovery factors.

The exploratory drilling density in Iraq’s 441,840 sq km is 1 well/2,900 sq km. Iraq is the least-explored Middle East country.

Iraq’s known oil reserves are roughly distributed almost one fourth in formations of Tertiary age, nearly three fourths in those of Cretaceous age, and a small percentage in Jurassic/Triassic.

Of 530 structural anomalies identified by geophysical means, the 113 wells established the presence of oil in 73. Reinterpretation of seismic using state of the art computer software indicates the presence of a large number of stratigraphic traps and many more structural anomalies than the delineated 530.

The new identified stratigraphic and structural anomalies, remaining identified but undrilled ones, untested shows, the many discovered fields—especially those in the south that are yet to be tested in the deeper (Lower Cretaceous, Jurassic, and Triassic) horizons, and Jurassic/Triassic oil resources in the relatively virgin Western Desert and the Folded Zone along the Zagros Belt will no doubt increase Iraq’s oil reserves to or beyond the latest estimates.

The author believes Iraq to be capable of increasing its oil production rate to 10 million b/d and possibly even to 12 million b/d.

Iraq tectonic framework

Iraq occupies the northeastern corner of the Arabian Plate, and over 95% of its territory lies in the Arabian Shelf units, whereas the rest, a narrow strip along the Iraq-Iran border, represents the Zagros Suture unit that separates the Arabian and Eurasian Plates.

Nearly all of Iraq is part of the Arabian sedimentary basin that extends from the Arabian-Nubian platform in the west and the Alpine folded geosynclinal units of the foredeep in the east. This vast sedimentary basin dates from the Precambrian.

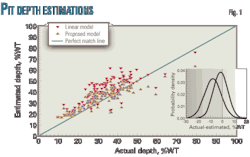

Iraq is made up of two main divisions of stable and unstable shelves of about equal areas (Fig. 1). The stable shelf occupies the west and southwest parts of Iraq, and the unstable shelf is in the east, north, and northeast parts of the country. Each is divided into a number of tectonic zones, and some of these are divisible into subzones.

Iraq is additionally dissected by a number of major NE-SW trending transverse faults that cut across both shelves and carry a strike-slip component of movement as well as a vertical component.

There are various structural plays that can be divided according to their prospects, geological age and tectonic setting to coincide with the tectonic framework:

• The stable shelf.

The stable shelf roughly coincides with the Western and Southern Desert geographic divisions of Iraq. It is tectonically divided into a western Rutba-Jezira Zone and an eastern Salman Zone separated by the N-S trending Salman-Sharaf Divide where the basement is at its shallowest (about 5-6 km below sea level).

Through gravity modeling and magnetic, seismic (though very limited), and supplementary oil and water well data (with few exploratory wells), the stable shelf is shown to possess thick sedimentary successions on either side of the Salman-Sharaf Divide. The successions principally consist of Paleozoic sediments.

• The unstable shelf.

It is divided into two main zones. The NW-SE trending Mesopotamian Zone extends across the alluvial plains of the Euphrates-Tigris valleys continuing from the Salman Zone to the Iranian border and wedging out in the NW in an apex. The second main zone is the Folded Belt that is subdivided into a Foothills Zone, a High Folded Zone, and an Imbricated Zone, extending over the foothills and ranges of Zagros and Taurus Mountains.

Iraq exploratory drilling

Iraq is almost entirely underlain by Silurian and-or Jurassic and Cretaceous rich formations of sufficiently mature source rocks.

Apart from the Cretaceous, the other prospects are only sparingly touched by the drill.

Of the 113 structures (counting both domes of Rumaila as one structure) that have been explored, 79 were successful (from 1903 to 1992), giving a success rate of 7 structures out of 10.

Exploratory drilling intensity increased from about 1.5 wells/year (88 wells in 59 years (1903 to 1962) during the concession era to nearly 3 wells/year (67 wells in 23 years, from 1969 to 1992). The overall success has been 3+ out of 4 wells; on a cumulative basis: 120 successful exploratory wells out of a total of 155, inclusive of delineation and deep test wells.

The percentage of successful exploratory wells in the country started at 50% and maintained a higher level at 77% by the time the Akkas well was drilled in the Western Desert in 1992 (Fig. 2).

So 155 wells were drilled to investigate 113 structures (excluding Ur and Um Qasr for lack of reliable information), i.e., a rate of 3 wells per 4 structures, which is a very low rate of exploratory wells (including delineation and deep tests) per structure.

Such low exploratory well intensity per structure suggests the requirement for further evaluation of the past dry or marginal fields.

What is rather unique is the fact that even during the initial phase of exploration from 1905 to 1939 the percentage of successful structures remained above 50%, increased to 70% by 1956, dropped to above 60% in 1960, and then started to build up gradually to its present level of 70%. And recent exploration in the northeast, carried out by independent oil companies, has demonstrated the same level of success.

Evolution of reserves

The buildup of reserves has been impressive.

Some 125.4 billion bbl (in accordance with per field estimate of the Petrolog & Associates 1997 study) of crude oil reserves have been discovered in 79 fields from 1903 to 1992, giving rise to 1.59 billion bbl/field, 900 million bbl/explored structure, and 810 million bbl/exploratory well.

It is important to note that the total reserve of 125.4 billion bbl includes 37 discovered but not developed structures whose reserves are not assessed. However, each has been assigned a conservative reserve figure of 100 million bbl. No doubt when these 37 fields are developed their true and realistic reserves will be revealed.

The official proved reserve figure stood at 100 billion bbl in 1989, was elevated to 112 billion bbl the next year, and was kept at this level until 2001 when it was raised to 115 billion bbl, giving original reserves of about 138 billion bbl, compared with the author’s estimate of 125 billion bbl then.

The reserves buildup from 1903 to 1992 was characterized by sudden large increases due to the huge reserves of the giant and supergiant oil fields, Kirkuk in 1927 (22.4 billion bbl), Zubair in 1949 (4.75 billion bbl), Rumaila in 1953 (27.25 billion bbl), West Qurna in 1973 (8 billion bbl), East Baghdad in 1976 (11 billion bbl), and Majnoon in 1977 (11 billion bbl). They were taken as the most likely from among the very many figures given by government and oil industry sources.

Clearly, Iraq’s reserves buildup has resulted from: new discoveries (successful wildcats), delineation wells (generally adding to the size of the structure), deep tests (adding further pays), further testing of prospective formations above or below the main pay (which often were not adequately evaluated), and from modeling and the occasional assessment of reserves with time.

These reserves figures allocate present reserves to the date of their discovery. Hence the sudden increase in reserves reflects the discovery of large fields, whereas the gentler buildup represents the addition of smaller ones or fields that have not had much growth of reserves since their discovery.

IPC and INOC exploration policy

There is a radical difference in the exploration policy of the concession era by Iraq Petroleum Co. and the nationalized era by the Iraq National Oil Co.

Oil discoveries in Iraq have given prominence to the Cretaceous and Tertiary petroleum systems over others. The exploration search during the concession era was sporadic and limited. Only discovered fields with a high oil production rate in excess of some 5,000 b/d/well were developed. The oil industry culture during the concession era was uniquely different since the rise of the national oil companies. I find it interesting to cite an example of the old practices.

A number of structures drilled by IPC and associated companies proved oil-gas formation but produced a relatively low production rate (around 100 b/d on test) and were classified unsuccessful and noncommercial. Some formations in many exploratory wells produced around 1,000 b/d, but the structures were left undeveloped.

Many tests were inconclusive due to technical problems, and a few prospective reservoirs such as Ratawi were bypassed. Other oil reservoirs such as the Mishrif were not tested conclusively enough to be classified as commercial, and a few were not targeted (the Yamama in the south or the Lower Cretaceous prospects in the Zagros Fold Belt) on account of depth or other drilling problems.

Clearly the concept of what was commercial was influenced by the price of oil (then, around $1+/bbl), the size of reserves in comparison to production commitment (the R/P ratio was never less than 50 since the Kirkuk discovery), and a host of other concessionary considerations and historically developed attitudes towards exploration and development.

Invariably every discovered structure in Iraq has multiple reservoirs.

The discovery of a good reservoir at shallow depth, such as Kirkuk field with huge oil reserves, appears to have precluded the early exploration of deeper prospects. The production system designed to handle the shallow reservoirs is not necessarily suitable to handle oil discovered later in deeper reservoirs.

A case in point is the early discovery of the prolific shallow Tertiary reservoir in Kirkuk. This had a great effect on the pattern of exploration in other areas, and the same or equivalent formations became the first objective for evaluation. The initial development of Bai Hassan and Jambur fields was for Tertiary production.

It was 23 years before the first deep test (K-109) in Kirkuk field was drilled, which led to the discovery of oil in the Cretaceous formations, and in which oil was also found in Bai Hassan and Jambur. In these fields no Cretaceous pay was fully developed during the period of the IPC.

In the Mosul Petroleum Co. area of northwest Iraq, the Tertiary formations were found to be poor prospects in which either heavy oil was discovered or low production rates were obtained, and drilling continued until reservoirs were penetrated in the Cretaceous at around 3,000 m and deeper. The main pays were then developed at Ain Zalah and Butmah in the Cretaceous reservoirs (the exception was one producing well from the Triassic in Butmah).

Likewise in the Basra Petroleum Co. area, the Tertiary was condemned when sporadic accumulations of heavy oil were found, and the Cretaceous formations became a target. The development of Zubair and Rumaila fields was devoted almost entirely to production from the major reservoir (Zubair formation) in each field.

The first well in Rumaila was drilled in 1953, following 25 wells in Zubair oil field. The main productive reservoirs of Zubair field were found to be present in Rumaila, and after 1954 virtually all development drilling was devoted to Rumaila: Oil was found in other reservoirs in the Cretaceous, but they were not considered sufficiently attractive to divert effort from developing the main pay.

Only one reservoir deeper than the main pay was partially developed in Zubair (the Fourth Pay), and none of the others at shallower depth were developed, e.g., the Mishrif.

Because of the fact that a good producer in Kirkuk oil field produced some 100,000 b/d and a good producer in Rumaila some 50,000 b/d, other discoveries where production was as low as 2,000 b/d or lower were naturally bypassed or capped and considered noncommercial.

More precise reserves focus

INOC as a government oil company adopted a different exploration philosophy. The assessment of the national hydrocarbon assets became an objective, and the race for production quotas among OPEC countries intensified the search for reserves.

Geophysical activities and exploratory drilling were increased. Assessment of other prospective formations (shallower or deeper than the main pay) became an objective in the discovered fields and in new structures.

The delay in appreciating the importance of the Cretaceous reservoirs and the almost total neglect of Jurassic/Triassic reservoirs may be explained as follows.

The discovery in 1927 of the prolific shallow Tertiary reservoir in Kirkuk had a great effect on the pattern of exploration in other areas. The same or equivalent formations became the first objective. The first deep test in Kirkuk (K-109) was begun in 1951, 24 years after the initial discovery of Tertiary oil, which had in fact led to the discovery of oil in the Cretaceous, namely Shiranish, Qamchuga, and Kometan limestone. For this reason the Cretaceous potential in the producing fields of the IPC area was not fully evaluated. In the MPC area, the Tertiary was found to be a poor prospect, and drilling continued until reservoirs were penetrated in the Cretaceous.

Similarly, in the south the development of Zubair and Rumaila fields was limited to the main pay zones of the Cretaceous. The full extent of the Tertiary reservoir formations and the many oil-bearing Cretaceous reservoirs above and below the pay zones were not evaluated until recently by INOC.

With sufficient oil reserves from these major fields, even discoveries as important as Nahr Umr, Kifl, Rachi, Dujaila, Ratawi, and Luhais were put on hold by the companies, as was the case with other giant structures like East Baghdad and Buzurgan that had been delineated by geophysical surveys.

Post nationalization, exploration and development work by INOC in the south has given better appreciation of the oil-bearing reservoirs of Mishrif, Hartha, and Nahr Umr, which are above the main pay zones, and of the deeper reservoirs of Ratawi and Yamama that have become targets of a deep drilling program.

No doubt the contribution of the oil reserves of these formations will add greatly to the upgrading of Iraq’s reserves.

The Jurassic/Triassic contribution has thus far remained negligible. The evidence of its presence in the many locations in the north and extending to the southern and western areas of the country is yet to be appreciated. Apart from the conclusions of regional geological studies that give a high degree of prospectivity, there is ample drilling evidence that tested oil presence.

INOC founded in 1964

In 1966, under the author’s supervision as executive director in charge of the technical departments, the INOC geological and petroleum engineering departments, jointly with a credible team of American consultants from Frank W Cole Engineering, carried out a study of potential oil reserves.

The studied area covered 215,000 sq km south of a horizontal line passing through the center of Iraq near Baghdad and bound by the Iraqi boundaries from the south, east, and west and excluding the area surrounding the major producing fields of Rumaila and Zubair. Only 18 wells were drilled in the studied area. Ten found oil in commercial quantities, and another two had encouraging shows.

A regional study of the area and the Middle East was carried out. Gravity, seismic, and geological surveys from IPC records were interpreted and structural anomalies derived.

Of 301 structural anomalies derived, only 135 were considered highly credible to produce oil, based on the study of new field wildcat success of 50% in this same general geological province of the Middle East in 1949-63.

An estimate of potential reserves was made from the total number of structures and volume of potentially petroliferous sediments multiplied by a recovery factor and a success ratio. The recovery factor was based on analogy with other discovered and produced reservoirs in Iraq. The success ratio was obtained from past exploration performance in the basin. The integrity of the structures was based on the results of weighing the stratigraphic, geological, and geophysical data.

In these 135 anomalies alone the potential oil in place in a part of the Cretaceous age formation was conservatively estimated to be in the order of 390 billion bbl and the potential recoverable oil was estimated to be in the order of 111 billion bbl.

Independent consultant in 1994

In 1994, the author presented a paper at a geological conference in Amman, Jordan, and developed it further a year later for a conference at the Centre for Global Energy Studies in London.

The paucity of published data (traps, plays, and related geology, seismic, gravity, etc.) makes it difficult to make anything other than an estimation of the order of magnitude of Iraq’s potential oil reserves. The approach adopted in that paper makes use of the empirical relationship between exploration and reserves buildup, where exploration effectiveness starts low at the initial phase, picks up sharply, grows linearly until the major part of the oil deposits are discovered, and then slows down as the ultimate reserves of the basin are approached.

An ‘S’ shaped curve resembles the relationship between cumulative discovered reserves and time or exploration effort, which lends itself to statistical and mathematical calculations, making use of log-normal and yule distribution functions.

With the aid of success ratios and the information in Fig. 3 the author successfully forecast Iraq’s reserves in 1994-95.

In Iraq some 530 structural anomalies have been identified by geophysical means. Of these, only 114 have been drilled and, by 1994, oil was established in 73 structural anomalies. The author estimated the total ultimate oil reserves housed in these 73 anomalies to be in the order of 144 billion bbl, which is in conformity with published data and the experience of Iraqi experts.

With the use of size distribution and varying success ratios, the potential oil reserve was estimated to be in the order of 280 billion bbl to 360 billion bbl, housed in 143 to 183 structural anomalies.

Based on the distribution and total reserves to date shown in Fig. 3, future potential oil reserves are estimated to be of the order of 280 billion to 360 billion bbl to be found in 143 to 183 additional oil fields out of the total remaining structures.

Of the 416 remaining structures only 286 (69%) were considered to have sufficient integrity to justify their acceptance. To these the overall success rate (per structure) 64% and the lower success rate (per wildcat) of 50% were applied.

The lower limit of 143 fields, giving rise to 280 billion bbl, is based on a success rate of 50%. The upper limit of 183 oil fields, giving rise to 360 billion bbl, is based on an overall success rate of 64% derived from an overall past exploration and drilling of 114 structures producing 73 successful discoveries.

These average success rates should have a good chance of being maintained, since they actually fall below the success rate of 73% for the more recent discoveries made in 1970-89.

The use of a 50% success rate implies that the latest success rate of 73% would have to decrease to 27% towards the end of the projected exploration time.

The degree of confidence in the above result may be examined in the light of the facts mentioned above, and summarized below, along with other evidence which the author gave at the time are as follows:

• 78% (416 of 530) of delineated structures remain unexplored. The success rate in locating oil in 1970-89 was 73% (38 of 52), which represents an improvement over and above the overall success rate of 64% (73 of 114). This indicates that the discoveries thus far should fall at the lower sector of the “straight line” section, justifying linear projection of the ‘S’ curve relationship relating oil field discoveries to exploration effort.

• The reserves in many of the discovered fields have yet to be increased to reflect the evidence of reserves in multiple reservoirs that have been established in the Tertiary and Cretaceous, in both the new and the known discoveries in the south, thus giving rise to a higher total reserve than the estimate of 144 billion bbl and, thus, to a higher average reserves per discovered field. In other words, the reserve per category could well increase as delineation work of the new fields proceeds and further development and evaluation of new discoveries and producing fields advances.

• The revaluation work and further drilling for the Cretaceous deposits lying below the known reservoirs in the northeast will add further oil reserves, ignored in the past.

• The Jurassic/Triassic promising prospects in the locations already drilled in the north, south, and southwest have yet to be evaluated, and further exploration wells are yet to be drilled, particularly in the area west and south of the Euphrates, which has already proved its prospective quality.

• The many possibilities existing for stratigraphic traps have not been explored.

• Many structures, particularly in the north, have been condemned by IPC and-or MPC either as dry or as containing gas or bitumen. No doubt some of these would have to be reexplored to prove them dry or successful.

• The discovery of Paleozoic oil in Saudi Arabia, the Akkas field in the western sector of Iraq, and the presence of a large number of delineated structural anomalies there, make the Western Desert a Paleozoic hydrocarbon province whose potential and reserves are yet to be evaluated.

The above stipulation is valid today as it was in the past.

Petrolog 1997 study

This is a more detailed and comprehensive study that took 3.25 man-years by a team of seven geologists, a petroleum engineer, and a mathematician.

In a joint study with CGES on Iraq’s Exploration Potential and Production Capacity in 1996-97, the Petrolog team, involving the author as coordinator and principal researcher and associates from among the most experienced petroleum engineers and geologists, carried out a four-volume comprehensive study. It covered Iraq’s proven and potential reserves.

The proven oil reserves were estimated at 128 billion bbl, housed in 80 fields, of which 124 billion bbl were housed in 43 discovered fields. The remaining 37 fields were discovered but not sufficiently delineated or produced. Each had been assigned only 100 million bbl. No doubt their reserves will appreciate when developed.

Iraq’s potential reserves were estimated conservatively to be in excess of 216 billion bbl. These are many large fields with as much reserves as in some of the discovered giant fields. The largest eight potential fields housed some 50 billion bbl, compared with 92 billion bbl housed in eight discovered fields.

Gravity, seismic, and geological surveys enabled preliminary estimates of the volume of sedimentary rocks. Estimates of potential reserves were obtained from the total number of structures and volume of potentially petroliferous sediments multiplied by a recovery factor and a success ratio.

The recovery factor was based on analogy with factors from other discovered and produced reservoirs in the basin. The success ratio was obtained from past exploration performance in the basin.

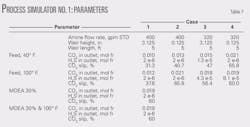

The integrity of the structures was based on the results of weighing the geochemical, stratigraphic, geological, and geophysical data. Throughout conservative reserves estimate parameters had been adopted (Table 1).

Petrolog reservoirs and oil parameters

The Petrolog estimate was based on conservative volumetric calculations using average porosity, oil shrinkage, and a recovery factor not exceeding 31% for the oil reserves recoverable from 224 anomalies among the total of 440 surface and subsurface identified anomalies that are sufficiently prospected to be included.

The potential proved reserve was estimated at 455 billion bbl, to which a success rate of 47.5% was applied (being the average of 70% terminating at 25% at the end of the exploration period), giving 216 billion bbl of proven reserves.

• Methodology and results.

According to Iraqi semiofficial publications there are 530 structural anomalies and leads, of which 239 are considered to have a high degree (some 70%) of certainty that are yet to be drilled.

Our study has identified around 440 surface structures and subsurface structural anomalies, identified from personal experience, geological maps, and geophysical data. Around 40 structures are located in the High Folded Zone, a difficult mountainous area in which little geological work has been undertaken (Fig. 1).

On further scrutiny and to err on the conservative side, a further major reduction brings the total to 231 anomalies. These are made up of 118 undrilled anomalies, in addition to the 113 anomalies which have been drilled, of which the majority, 106 anomalies, have prospective formations at their location. This brings the prospective anomalies with undiscovered reserves to 224.

• Main reservoir pays.

Tables 2 and 3 show a number of significant reservoirs and discovered fields in the central and southern parts of Iraq. The production capacity per well for any one reservoir pay is preliminary in nature, often quoted from initial tests that have neither been treated for enhancement nor produced for sufficient duration to confirm credibility.

Clearly, the production rates for the new reservoirs are tentative, but low production rates are well established in most fields and for almost all the new reservoirs reviewed above.

Apart from the Cretaceous Zubair sandstone of Rumaila South field, where the average production rate per well is some 15,000 to 20,000 b/d (and to a lesser degree Zubair field with 4,000-5,000 b/d), typical rates elsewhere in the new fields farther from Zubair and Rumaila are only some 10% of the above high-rate Zubair sandstone. The newly discovered fields in the south, southeast, and central areas give low production rates from newly developed reservoirs (Table 3).

• Reserves of reservoir formations.

Potential reserves by formation are given in Table 4. These yet-to-be-discovered potential reserves appear to be in the following descending order: Najmah, Zubair, Kura Chin, Yamama, Mauddud, Jeribi+, Hartha, Nahr Umr, Khasib/Sadi, Akkas, Shiranish, and finally Mishrif.

The reserves of the Mishrif have proven much larger as a result of the oil presence covering a much wider area than previously assumed and the use of a higher recovery factor.

The total ultimate undiscovered potential reserves are thus 455 billion bbl of oil. This estimate was, however, based on an exploration success of 100%. Accepting that the high initial success ratio of 70%, which has been the norm in Iraq, will decrease with time to a conservative 25%, the average success ratio of 47.5% during the remaining exploration period gives ultimate undiscovered reserves of 216 billion bbl.

The undiscovered reserve per drilled anomaly of about 1 billion bbl is of the same order of magnitude, if slightly smaller, than the 1.2 billion bbl for discoveries to date.

The study indicates that there are supergiant fields, the largest of which could be comparable to Kirkuk or Rumaila fields (Fig. 3). However, the distribution is more even than the oil discovered so far, since the first eight fields of undiscovered reserves represent about 23% of total undiscovered reserves, while the comparable figure for discovered reserves is higher than 70%. They show a great number of giant fields, with some 30 structures, each with more than 2 billion bbl of recoverable reserves, with an average of just under 4 billion bbl each.

With access to a substantial database on Iraq, INOC estimated 212 billion bbl of oil yet to be discovered, which is remarkably close to the estimate obtained in this study. Without more information on the details of INOC’s calculations, it is difficult to compare the two results, but it seems that we have fewer anomalies on which future discoveries are to be made, while our average discovery size is larger.

An attempt was made to use a probabilistic approach to estimate undiscovered reserves, but a deterministic approach was finally accepted to be more appropriate, taking into consideration the data available and the scope of the study. The size distribution of reserves in Iraq shows typical log-normal distribution. An examination was carried out of the distribution of all Iraqi ultimate and potential reserves.

Iraq’s oil resource base

A comparison of the present reserves with the potential, which make up the resource base, is given in Table 5.

Iraq’s oil reserves stood at 115 billion bbl until November 2010, when the Ministry of Oil announced a revision to 143.5 billion bbl while the potential reserves stood at an estimate of around 215 billion bbl, which is in line with the only study of the ministry’s at 212 billion bbl and Petrolog & Associates’ study of proved reserves at 120 billion bbl and 216 billion bbl in the 1997 study.

The Tertiary reserves will add some 19.6 billion bbl, the Cretaceous some 159.2 billion bbl, and maintain its high share of the total, the Precretaceous some 37.1 billion bbl and increase its share of the total (Fig. 4).

It is anticipated, however, that the Precretaceous will at least be double the estimate here, since during the time of the 1997 study no seismic or exploratory drilling has been carried out, while recently much exploration has been carried out in the northeast uncovering substantial amounts of reserves.

Iraq’s latest reserves increase

The ministry, in its November 2010 announcement, considers 34% recovery is applicable to 66 upgraded fields.

Iraq reserves have been revised to 143.1 billion bbl. Supergiant West Qurna field’s recovery rate is now 42%, giving it 43.3 billion bbl, and supergiant Kirkuk field has the highest recovery factor, 58%. The rate in complex fields is around 15%.

The bulk of the increased reserves came from West Qurna, where the reserves were doubled to 43.3 billion bbl. Past practice limited the recovery to 15-31% for most of the fields except Kirkuk and Rumaila, which were given a higher recovery factor.

Iran used small increases across various fields to justify its modest jump to 150.3 billion bbl from 138 billion bbl in a hurry to better Iraq. It has been reported that Iran uses an average recovery rate of 20-25% to calculate its reserves. This, indeed, assumes very conservative estimates though may prove to be generous for newer fields like Azadegan, where the likely figure may be 10-15%, judged by the generality of its oil and reservoir characteristics.

Saudi Oil Minister Ali Naimi addressed the issue recently, saying, “Initially when a field is discovered, they say ‘We can recover 17%’ because they don’t have any experience with producing that field. As time goes by and they drill more wells and see the reaction of the reservoirs, they say, ‘Well, I think we can recover 35%.’ And finally the average that the industry believes can be done is about 50%, and 50% to 60% at fields like Ghawar are within reach.”

BP had achieved 50% over a decade ago in the North Sea, and 60% had been achieved but sparingly in the North Sea and elsewhere. The industry target is 70% and above.

However, to extract oil from the very marginal fields, oil prices above the present floor of $40-50/bbl would have to support capital costs at a higher level than currently prevail.

Can Iraq achieve 12 million b/d?

At a depletion rate (production/reserves, P/R) of 4-5%/year, Iraq can continue its upward production rate to 10 million b/d and beyond to 12 million b/d conditional on, in the case of the latter rate, adding new potential reserves so as not to exceed the above depletion rate (Fig. 5).

While developing 10 million b/d is achievable within good oil industry practice of allowing an annual depletion rate of 4-5%, with no exploration, the results are not as robust, but they are still robust enough.

Building Iraq’s current production rate to a peak of 10 million b/d and maintaining the plateau for 8 years would require a P/R of 4% at the beginning, rising to 5.3%, when it is allowed to decline. At the end of 25 years the production rate would be 6.4 million b/d, but the reserves would have declined to some 42 billion bbl from 115 billion bbl at the start of the buildup.

To build to 12 million b/d and maintain P/R at 4-5% would require additional reserves to supplement the current 115 billion bbl remaining reserves. In this case, additional reserves of 3 billion bbl/year need to be added, starting from the seventh year. The plateau is maintained for 8 years as the remaining reserves decline to 98 billion bbl.

By the end of the 25th year, the production rate is 11 million b/d and the remaining reserves are 91 billion bbl, with the P/R being kept within the desirable depletion. A total of 57 billion bbl from new discoveries have to be added, which represents only 26% of Iraq’s likely potential reserves.

The production rate at the end of the 25 years is still a healthy 6.4 million b/d, and the remaining reserves some 48 billion bbl.

The 12 million b/d rate requires additional total reserves of 57 billion bbl, which is fairly feasible to be added at an advanced stage of development at an annual rate of 3 million b/d to ensure sustaining a healthy depletion rate at 4-5%.

And, conservation of reservoir energy, optimum reserves recovery at least cost can be at risk if and when the highest production plateau is predetermined, as the case in Iraq’s contracts, which ignores the uncertainty associated with prejudging its level. There is an intrinsic relationship between depletion rate of reserves and recovery. A balance between the two can only be obtained by development in stages while observing and evaluating reservoir reaction.

Iraq oil service contracts commit some 83 billion bbl to attain a plateau of 12 million b/d. This requires a higher depletion rate than 5%, which could well risk achieving less-than-optimum recovery and would likely be at a higher unit cost. Therefore, the oil production plateau and its targeted duration stipulated in Iraq’s contracts ought to be complemented not only by the anticipated enhanced recovery but also by additional reserves from within and-or without the contracted fields.

Conclusion: Iraq’s reserves

Iraq proved reserves have been recently revised to 143 billion bbl from 115 billion bbl based on an assumed higher recovery factor.

While higher recovery rates in Iraq should prove fairly likely, these can be justified following future production observations of sweep efficiency and relevant reservoir parameters with the aid of 3D seismic surveys. Oil-water and oil-gas contacts and subsurface pressures are examples of factors that enable material balance calculations to be made to ascertain the validity of recovery rate estimates.

Uncalled for conservatism in estimating reserves can be as costly as in optimistic estimates.

The cost of oversized production infrastructure beyond the fields’ boundaries to the export flange (such as transfer lines, storage tanks, and terminals) represents a waste of capital investment and so is the case for underdesigned capacity. The latter is just as costly as it eventually requires additional capital investment with a loss of the economies of scale.

Iraq’s use of recovery rates below global averages accounts, in part, for Iraq’s past adoption of outdated technology and poor production practices during the periods of the Gulf Wars, sanction years, and since 2003. Kirkuk and Rumaila have had their share of potential damage.

On the basis of the studies described in this article, potential reserve growth from future discoveries and likely future enhanced recovery of Iraq’s oil, the present estimates of proved reserves of 115 billion bbl and a potential reserve in excess of 216 billion bbl should prove fairly certain, with a high probability to be exceeded.

The total present Iraqi oil resource base of 331 billion bbl assumed at 31% recovery, an improvement by 15% (well within the future art of technology and Saudi present achieved recovery) would make Iraq’s resource on a par with Saudi Arabia’s, if not higher.

The authorMore Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com