HAYNESVILLE UPDATE—2: North Louisiana drilling costs vary slightly 2007-12

Mark J. Kaiser

Yunke Yu

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge

Well construction costs comprise the largest component of the capital expenditures required in onshore developments, typically ranging 70-90% of total project costs. Thus, the cost to drill and complete wells and the ability to innovate and reduce costs over time are among the primary components in the profitability of onshore plays.

This is the second in a series of four articles on the Haynesville shale. Part 1 focused on the decline of Haynesville production over the last 2 years (OGJ, Dec. 2, 2013, p. 62). In this part, we evaluate well construction costs in the Haynesville shale 2007-12 and present detailed cost statistics, distributions, and correlations at both a regional and operator level.

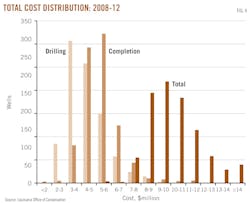

We find that more than half the wells constructed in the Haynesville shale since its discovery cost $8-$11 million to drill and complete. The average Haynesville well costs $9.95 million and completion expense is responsible for most construction costs.

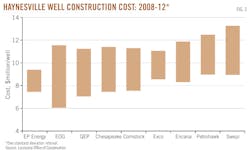

EP Energy LLC realized the lowest average drilling and completion cost at $8.4 million/well and the highest average cost among leading operators was Swepi LP at $11.1 million/well.

Cost data

For all horizontal wells drilled or completed in Louisiana where production began after July 31, 1994, the state provides a severance tax exemption for 2 years or until payout of drilling and completion costs is achieved, whichever comes first (La. Revised Statute 47:633(7)(c)). Applicants for severance tax exemption are required to submit well construction cost data to receive the exemption, and it is these data that form the basis of our analysis.

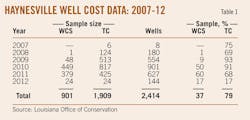

From 2007-12, well cost data were available for 1,909 Haynesville wells out of 2,414 wells drilled during the period (Table 1). Detailed drilling and completion data were reported for 901 wells with a well cost statement (WCS) and represent a subset of the total cost (TC) data.

Total cost data were available for 79% of all wells drilled in the Haynesville during the period and WCS data were available for 37% of wells. Since severance tax exemption is only granted for producing wells and not all drilled wells are completed and produce within the calendar year, the coverage statistics do not coincide with the reporting period.

In 2009-10, more than 90% of all wells drilled reported TC data, and in mid-2010 when the WCS form was first introduced, more than half of all wells reported WCS data. Low coverage rates in 2012 are due to applications in review at the time of the evaluation and are not a statistically significant sample.

More than 70% of the sample wells are in DeSoto, Red River, and Caddo parrishes and represent the primary producers in the region, Chesapeake Energy Corp., Exco Resources Inc., PetroHawk Energy Corp., Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc., and Swepi.

Cost statistics

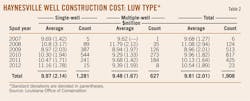

The average cost to drill and complete a Haynesville well in 2007-12 was $9.8 million with a standard deviation of $2 million (Table 2). In 2008, the average cost to drill and complete the average 14,700-ft measured depth (MD) and 4,470-ft horizontal length (HL) well was $11.1 million. In 2011, the average cost to drill and complete the average 16,660-ft MD and 4,770-ft HL well was $10.1 million.

All other things being equal, well costs should increase with drilled interval and well complexity, but all other things are rarely equal because of changes in market conditions, technological innovations, productivities, locations, and other factors. Average well construction cost varies about 10%/year.

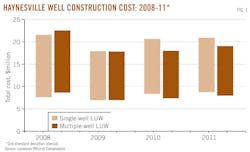

Single-well lease unit wells (LUWs) averaged $10 million/well and multiple-well LUWs averaged $9.5 million during the evaluation period. In 2008, the average multiple-well LUW cost about $1 million more than the average single-well LUW, while in 2010 and 2011, multiple-well LUWs cost about $1 million less than single-well LUWs (Fig. 1).

Drilling multiple wells on the same unit would presumably lead to better economics and improved learning curves. Average well construction costs should be less on multiple-well LUWs when compared with single-well LUWs. Unfortunately, aggregate average statistics alone cannot determine learning, scale, or the lack thereof due to constantly changing market conditions and other factors that are not easily normalized.

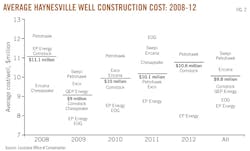

Chesapeake, Exco, and Petrohawk are leading producers in the Haynesville, and each has drilled more than 200 wells in the formation since 2008. Encana, Swepi, and EP Energy also have extensive operations in the region. Operators that have drilled fewer than 100 wells include Comstock Resources Inc., QEP Energy, and EOG Resources Inc.

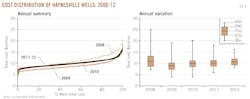

Chesapeake and Petrohawk were early participants in the Haynesville, and in 2008 their average well construction costs were $9.3 and $12.2 million, respectively (Fig. 2). Chesapeake's average well cost dropped in 2009 to $8.3 million on 186 wells drilled, increased to $9.7 million in 2010 on 231 wells drilled, and increased again in 2011 to $10.7 million on 121 wells drilled.

In 2010, Exco's well cost averaged $10 million 113 wells. The company spent an average of $9.5 million in 2009 and 2011 on 42 and 83 wells, respectively. Petrohawk's average well cost was among the highest among active drillers in 2008-10, but in 2011, the company's average cost was less than the industry average.

EP Energy realized the lowest overall average drilling and completion costs over the period at $8.4 million on 120 wells drilled (Fig. 3), followed by EOG ($8.8 million on 48 wells), QEP Energy ($9.2 million on 61 wells), and Chesapeake and Comstock ($9.4 million on 690 wells). Swepi's and Petrohawk's average well construction costs were the highest among leading operators at $11.1 and $10.7 million, respectively.

There is no evidence that companies that drill more wells have lower costs than the industry average. EP Energy and Exco maintain the smallest cost deviations in the cohort, which may indicate better cost control, regionally concentrated drilling, standardized completion designs, or related factors.

Cost distribution

Haynesville well construction cost is lognormally distributed and almost all wells require at least $7 million to drill and complete (Fig. 4). Sixty-two percent of all wells constructed during the period cost $8-11 million, 21% of wells cost $11-15 million, and 12% of wells cost $7-8 million; 4% of wells cost more than $14 million.

In 2008, 25% of all wells cost more than $12.5 million, but this percentage has since dropped (Fig. 5). In 2010-11, about half of wells cost more than $10 million. Average well construction cost has not changed significantly over time, indicating that the characteristics of the formation (hot, deep, and overpressured) have so far constrained efforts to reduce cost.

Completion operations cost more than drilling and both exhibit a rightward skew (Fig. 6). Completions may take several weeks or longer to set up and perform and, because of the extensive material, labor, and equipment requirements, represent a large portion of well construction costs.

Average drilling costs were $5 million in 2009, $4.3 million in 2010, and $4.8 million in 2011. Average completion costs were $5.6 million in 2009, $5.3 million in 2010, and $5.3 million in 2011.

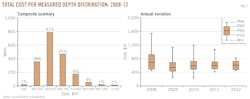

Eighty-five percent of all wells drilled and completed 2007-12 cost between $400-700/ft/MD (Fig. 7). Average footage cost and standard deviation are $584/ft and $119/ft, respectively.

Correlations

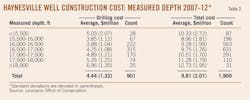

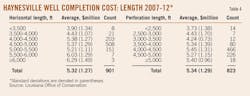

Average drilling and completion costs increase as wells are drilled deeper and longer and with greater lateral displacement (Tables 3 and 4). Standard deviations range 20-30% of the average category cost and reflect the aggregation process and variation in drilling and completion strategies. For the most part, the categories are well populated, but small sample sizes at the ends of the spectrum may be inadequate to compute representative averages.

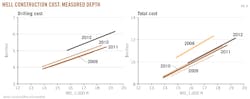

Construction and drilling cost by well and per foot is positively correlated with measured depth (Fig. 8). Parallel curves indicate common influences in cost determination.

Completion costs exceed those for drilling and are responsible for most well construction costs (Table 5). In 2009-12, completion operations represented 52% of total well costs compared with 44% for drilling operations.

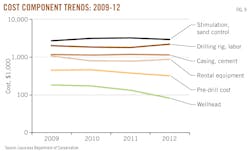

Stimulation and sand control are the primary cost components in construction, followed by rig dayrates and labor, casing and cement services. Rental equipment is also a major cost component.

The relative importance of cost components change little over time (Fig. 9).