Russian Arctic presents opportunities, difficulties for IOCs

Anna Ovcharova

Repsol

Moscow

Eduardo G. Pereira

Siberian Federal University

Krasnoyarsk, Russia

The Russian Arctic Zone’s (RAZ) remote location and harsh climate poses difficulties for development, but vast reserves make the area attractive for investment. Based on 2020 worldwide reserve estimates, the Arctic has about 8% of global undiscovered conventional oil resources and 23% of global undiscovered conventional gas resources. In general, North American Arctic regions tend to have more oil resources, while the Eurasian region tends to be richer in gas (Fig. 1).1-3

Russia’s current regulatory framework makes international oil company (IOC) participation difficult without a strategic local partner such as a national oil company (NOC) or major domestic oil and gas company. Large natural resources combined with potential new trade routes, however, have motivated IOCs to form several joint ventures with NOCs.

Russia’s national strategy for RAZ development includes new ports, year-round shipping along the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and promoting LNG and oil projects. These initiatives make joint ventures with NOCs more attractive for IOCs.

Another important initiative is the draft law for hydrocarbon development on the Russian Federation continental shelf in the Arctic and Pacific oceans. The law presumes that private companies will develop hydrocarbon resources in cooperation with an agent of the Russian Federation through consortium agreements. The Russian Government agent, in the form of a state-owned entity, will have at least 25.1% interest in a project (with proportional increase depending on the volume of the field). The remaining will go to private investors. The agreements provide more flexibility in corporate management and makes it possible to apply Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN) joint operating agreement standards for structuring cooperation. The draft law is currently passing ultimate alignment procedures before being presented to the State Duma. With new agreements in place, participation of IOCs in the RAZ is expected to increase.

RAZ challenges

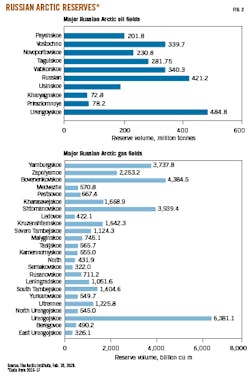

Significant oil and natural gas discoveries in the Arctic began in Russia with Chibiukskoye field in 1931 (Republic of Komi). Commercial production started in 1939, followed by the discoveries of Tazovskoye field (1961), Urengoy field (1966), Yamburg field (1969), Bovanenkovskoye field (1971), and others.4 Large Russian Arctic oil and gas field reserve volumes are shown in Fig. 2.

The Arctic’s remoteness and harsh climate make resource development hard. Opportunities for investment in license blocks located in the RAZ may be limited. Every investor will be faced with:

- Extreme weather and climate conditions, including low temperatures, permafrost, strong winds, and sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean.

- Remoteness from main commercial and production centers (i.e., dependence on supply of goods and services for basic needs from other regions of the Russian Federation, often only available for portions of the year).

- Fragile ecological systems.

- Lack of cutting-edge technology for development, including exploration for hydrocarbon deposits in severe arctic conditions.

- Poor labor productivity from lack of professional employees in the area.

- Huge capital and operational expenses and high levels of amortization of capital assets, including transport and energy infrastructures with relatively low extraction and production efficiency.

- Challenging regulatory circumstances, such as restrictions on transfer of certain goods and services to the RAZ (i.e., sanctions).

Additional challenges for Arctic oil and gas development from 2016-20 came from low crude oil prices and ongoing concerns about climate change.5 Regardless, international interest and attention are increasing as ice melts and the Arctic heats up. The combination of natural resources, potential new trade routes, and strategic interests opens the possibility of changing international dynamics.

Development of natural resources therefore depends on strategic decisions from regulators, investors, and other stakeholders across the Arctic region. Although some risks and concerns might be shared across the region, this paper focuses on key roles that Russian NOCs might play in developing the RAZ and how their views might differ from IOCs.

IOC vs. NOC

With Russia’s current regulatory framework, IOCs cannot participate independently in many RAZ projects, and it is not possible to explore the RAZ without a strategic local partner such as an NOC or major domestic company. Main actors in the RAZ remain Russian NOCs and private Russian oil and gas companies. Oil projects involve PJSC Rosneft, PJSC Gazprom Neft, and PJSC Zarubezhneft. Gas projects involve PJSC Gazprom and JSC Novatek.

Russian NOCs have different objectives in Arctic exploration and development than either Russian private companies or IOCs. NOCs usually have support from the Russian State. They generally follow and implement Russian Federation policy in relation to relevant projects, especially those in strategic geographical areas such as the RAZ. The Russian State places importance on RAZ development and closely follows progress of projects assigned to its NOCs. Macroeconomic trends, the recent pandemic, and lack of partners and resources therefore will not necessarily lead to suspension or termination of these projects.

Commonly, NOCs secure relevant permissions from the Russian Government without challenges (including offshore Arctic licenses) and later might secure partners including IOCs, not only to share financial and geological risks but also to take advantage of the IOC’s experience, knowledge, and technologies. At different times, however, there might be different partners to NOCs from different jurisdictions: US (ExxonMobil, Chevron, etc.), UK (bp PLC), EU (Eni SPA, Total Energies, Royal Dutch Shell PLC), Norway (Equinor ASA), and Japan (Mitsui & Co., Mitsubishi Corp., Inpex Corp.).

IOC-NOC joint ventures

Fig. 3 shows examples of cooperation between IOCs and NOCs in the Russian Arctic. Some of these projects have been terminated or suspended, and some do not have a clear future.

State-owned Rosneft actively promoted an international model of Arctic offshore development and at different times offered foreign and Russian oil companies a 33.3% stake to explore offshore oil fields in Barents and Kara Seas. In Barents Sea, Eni received two blocks, Fedynsky and Tsentralno-Barentsevsky, in the former grey zone or disputed area, and Statoil (now Equinor) contracted for Perseyevsky block.6 In Kara Sea, Vostochno-Prinovozemelsky (East Prinovozemelsky) block went to ExxonMobil, and in 2014, Karmorneftegaz, the joint venture between Rosneft and ExxonMobil, drilled the Universitetskaya-1 exploration well in the block post US and EU sanction restrictions.7

Environmental monitoring and protection are two main problems for offshore Arctic drilling. To address these issues, Rosneft and ExxonMobil created the Arctic Research and Design Center for Offshore Developments to support research on developing Arctic offshore fields and environmental monitoring.

Many Arctic projects have been negatively affected by US and EU Ukraine-related sanctions, which specifically target Russian Arctic offshore projects, banning the transfer of relevant equipment and technologies from the US and EU. Russian state-owned oil companies were forced to consider the impact of foreign sanctions on their activities.

Some Rosneft foreign partners started exiting joint projects to comply with imposed restrictions. In March 2018, ExxonMobil announced in its report to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that it had started exiting projects with Rosneft which were affected by sanctions, completing the process in 2019. ExxonMobil valued the losses at $200 million.8

Gazprom Neft also attracted foreign investors in Arctic projects, only to see them unravel due to bureaucratic and financial impediments. In 2019, Gazprom Neft and Shell signed a deal to develop Meretoyakhaneftegas in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous district. However, since the project concerns development in a federally strategic area, governmental commission approval was required to complete the transaction. The approval was not obtained by the agreed end-2019 deadline. Due to this missed deadline and the negative influence of macroeconomic factors, including COVID-19 and the April 2020 oil price drop, Gazprom Neft and Shell announced that the joint development project had been terminated. Gazprom Neft will continue to develop the project on its own.9

The Gazprom-Total Shtokman venture has also been terminated and Gazprom will pursue this opportunity on its own.10 Likewise, the Rosneft-Statoil (Equinor) alliance has unwound and Rosneft continues to work on those licenses on its own.

Recently, IOC interest in the arctic has been on the rise. In 2020, Equinor acquired a stake in a Rosneft subsidiary operating in East Siberia, Shell joined a JV with Gazprom Neft for development of the large hydrocarbons cluster on Gydan peninsula, and Trafigura Group Pte. Ltd. took a 10% stake in Rosneft’s major Vostok oil project.11

Commercial interests

Initial goals of Russian NOCs as commercial entities are the same as those of IOCs. The projects need to be commercially viable and thus investment decisions should be taken based on clear economic parameters. However, end goals might be slightly different as NOCs are driven by both commercial triggers and political motives. Thus, when IOCs leave projects, due to macroeconomic or political reasons, Russian NOCs will most likely stay and attempt to continue at their own expense despite questionable economics. The departure of Shell from the Meretoyahaneftegaz project is a case in point, with Gazprom Neft citing changes in the macroeconomic environment as one of the reasons for departure. The same occurred with the Shtokman project when both IOCs left the project with Gazprom because they were not able to arrive at viable technical and commercial decisions. Nevertheless, Gazprom continued with the project and eventually decided to put the work on hold as the economic environment was not conducive to development.

If partners cannot agree on a common way forward, there are joint-venture contractual options that allow companies to develop projects as sole risk. Sole-risk provisions allow exclusive operations when not all project parties are willing to participate. A sole-risk clause is used when a proposal of work is not approved by the JV operational committee. In this case, a party that desires to proceed independently will have the right to carry out the proposed work at its sole risk and cost. Additional complexities might arise, however, from separate accounts, operatorship, trust, and a possible exorbitant buyback premium.

The reasons for a NOC to introduce sole-risk mechanisms are understandable, however, an IOC typically cannot take such an approach. In the Russian legal framework, the IOC is typically a shareholder or participant to the legal entity holding the license and is generally liable for both joint and sole-risk operations.

In sole-risk operations in which an IOC is not willing to participate, under Russian law IOC interests are protected against liability for sole-risk activity conducted by an NOC through compensation of expenses (such as analogues of indemnities, provided in the Russian Civil Code, Art. No. 4061). This measure of protection, however, might not be sufficient due to continuing lack of trust in the Russian dispute resolution system. In addition, such instruments of possible protection of the interests of an IOC in the sole-risk set up have not been well tested, and there is lack of case law in this area.

Way forward

Russia continues to consider RAZ as a strategic part of its territory. On Oct. 26, 2020, Russian president Vladimir Putin approved the strategy for developing RAZ to ensure national security up to 2035. Among other aspects, focus is given on further development and capacity increase of the NSR. To achieve this goal, many logistic, administrative, regulatory, and infrastructure problems need to be resolved.12

Problems posed by severe weather, lack of local and highly specialized technologies, and reliable and skilled labor sources could be successfully addressed with IOC joint ventures. Positive examples are the Yamal LNG project between Total, China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), Silk Road Fund, and PAO Novatek, and the Rosneft joint venture with ExxonMobil for Barents and Kara Seas. IOCs brought their knowledge and experience of offshore exploration in Arctic zones into joint ventures with Russian NOCs. Specialized labor sources, provided by IOCs and NOCs, were also engaged in exploration activity.

The national strategy for developing RAZ envisages three stages of implementation. The first stage includes development of new ports in the NSR and updates to Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extension claim to the continental shelf, which is currently with the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.13 The second stage, 2025-30, gives priority to year-round shipping via the NSR. By 2025 Russia plans to deliver Arctic fiber-optic communication cables and start construction of an RAZ hub system to deliver trans-Arctic shipments. The third stage emphasizes LNG and oil projects across the RAZ. The strategy aims to address infrastructural concerns of IOCs and NOCs and ensure further development of the northern seaports.

For instance, the Murmansk region, home to Russia’s sole non-freezing Arctic port, will receive new terminals. Rapid development and construction of large offshore structures to produce, store, and ship LNG will be prioritized in the region. Development of the Sabetta seaport and dredging a sea shipping channel to the Gulf of Ob will be priorities. Railway networks will be expanded, a pipeline gas system will be prioritized for the Gulf of Ob, and the Yamal Peninsula gas projects will be broadened. As a result, it is expected that the NSR will be a competitive global transport corridor by 2035.14

Under the current regulation and draft laws being prepared, it will be possible to receive financing from federal and local budgets.15 Draft legislation will provide the basis for controlling major participation interests of IOCs in RAZ projects through consortium agreements.16 17 This concept of consortium in relation to the hydrocarbons license rights is new to the Russian legal environment. It provides more flexibility in corporate management and makes it possible to apply AIPN joint operating agreements for structuring the cooperation.

Supplementing these regulatory overhauls are tax incentives and measures of tax support which include:18

- No export customs duty (effective for projects in the north of Barents Sea and in the Eastern Arctic until Mar. 31, 2042).

- Separate procedures for calculating taxable profits of new offshore deposits.

- Reduced taxation to 5% within 15 years of starting commercial production in new sea deposits across more than 50% percent of the Laptev, Kara, Pechora, Beloye, Barents, East Siberian, Chukchi, Bering, and Japanese Seas.

- Tax exemptions for company property on the continental shelf and zero transport tax for stationary and floating platforms, offshore drilling rigs, and vessels.

It is not yet certain whether the above measures will be enough to encourage IOCs to invest in the RAZ. The perception is that the Russian Arctic is delaying opening for private investors, leaving the major role in developing the RAZ with Russian NOCs having a majority of state participation. Contrary to this perception, there have been quite a few joint ventures in relation to RAZ in between NOCs and IOCs. Despite cessation of some joint activities, NOCs have continued cooperative operations rather than developing projects alone.19

Another important initiative could be further work on the draft law “On the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation,” dealing with, among other things, creation of special support zones with specific investment regimes for Arctic projects. Foreign sanctions, however, may still be difficult to overcome by the relevant stakeholders until these sanctions are eased or repealed.

References

- US Energy Information Administration – International Energy Statistics, 2020.

- Aleksandrovich, S.V. and Kabalin, M., “Western Arctic shelf of Northern Eurasia: reserves, resources and production of hydrocarbons until 2040 ND 2050,” Neftegaz.RU, No. 11, Nov. 13, 2019.

- Tudorache, V. and Antonescu, N., “Challenges of oil and gas exploration in the Arctic,” Journal of Engineering Sciences and Innovation, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2019, pp. 273-286.

- TASS editorial staff, “History of the development of the Russian Arctic,” TASS International Arctic Forum, April 9, 2019.

- Alifirova, A., “On your own. Gazprom Neft will continue to implement the Meretoyakhanenftegaz project without Shell,” Neftegaz.RU, Apr. 14, 2020.

- “Rosneft in 2017 will conduct seismic exploration at the Perseevsky subsoil block in the Arctic,” Neftegaz.RU, Nov. 9, 2016.

- “Rosneft and ExxonMobil start drilling in the Kara Sea,” Rosneft press release, Aug. 9, 2014.

- “ExxonMobil named the amount of losses from the gap with Rosneft,” Regnum, Mar. 1, 2018.

- “Gazprom Neft will continue to develop the Meretoyakhanenftegaz project independently,” Gazprom Neft press release, Apr. 13, 2020.

- “Total left Shtokman Development,” Interfax.RU, Jul. 29, 2015.

- Griffin, R., “Equinor acquires 49% interest in Rosneft subsidiary operating in East Siberia, S&P Global Platts, Dec. 11, 2020.

- Burdina, A., “Stumbling ridge,” The Arctic, Nov. 15, 2018.

- “Russia will continue research in the Arctic to submit new data on the shelf boundary to the UN,” Finmarket.RU, Mar. 16, 2020.

- Buchanan, E., “Russia’s Grand Arctic Plan Will Face Tough Hurdles,” The Moscow Times, Oct. 28, 2020.

- “Yury Trutnev: The first step has been taken,” The Arctic, Oct. 16, 2020.

- Lyons, M., “Risk to Arctic Energy Exploration,” Global Risk Insights, Oct. 28, 2020.

- Polovtseva, M., “Never too late: Russia Hydrocarbon Development in the Arctic,” The Arctic Institute, Jun. 30, 2020.

- Krutikov, A., “The development of the Arctic will go according to plan, but adjustments are inevitable,” Pro-Arctic.ru, Sept. 4, 2020.

- Snyder, J., “Fleet of ice-breaking carriers propel Russia’s Arctic LNG ambitions,” Riviera, Oct. 29, 2020.

Authors

Anna Ovcharova ([email protected] ) is a head of legal Russia at Repsol in Moscow. She has an MS (2004) in law from Lomonosovs Moscow State University, Russia, a LLM (2008) in international and comparative law from Rijks Universtiteit Groningen, the Netherlands, and a PhD (2013) in Comparative and International Law studies from the Russian Academy of Science. She is a member of AIPN.

Eduardo G Pereira ([email protected]) is a professor of natural resources and energy law as a full-time scholar at the Siberian Federal University and adjunct or visiting scholar. He has a BS (2007) in law from the Universidade Católica de Pernambuco, Brazil, and an MS (2010) and PhD (2011) in law from the University of Aberdeen.