Emulsion fuel options still viable for heavy oil

Venezuela was until recently the only source of a unique fuel option that bypassed the traditional yet capital intensive two-step conversion of bitumen-extra heavy crudes(B-EHC) to synthetic crude oil (syncrude) and then to refinery products.

Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) and its subsidiary Bitumenes Orinoco (Bitor) had shown that it was possible to tap Venezuela’s enormous reserves of bitumen in the Orinoco Belt quickly via the production of its proprietary fuel Orimulsion—a 70% bitumen and 30% water emulsion with a surfactant exported as a boiler fuel for power generation.

In 2003 major supply contracts had been approved and signed for power plants in Asia and Central America where the pricing of Orimulsion was then indexed to gas or oil, rather than coal. Its positive use in Denmark and the US Environmental Protection Agency’s report had established that under adequate safeguards Orimulsion could comply with all environmental legislation as well as any other hydrocarbon fuel source.

The technical success of Orimulsion as a fuel for Wartsila generators opened up new horizons, with a new plant in Guatemala designed specifically to be used with the fuel.

As PDVSA declared in its 2003 filing to the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the Orimulsion business plan called for expanding its production capacity through joint ventures to 19.5 million tonnes (300,000 b/d) by 2006 from 6.5 million tonnes/year (100,000 b/d) in 2003.

For PDVSA and the Ministry of the Power of the People for Energy and Petroleum (MPPEP) there was every reason to feel proud of the 100% Venezuelan breakthrough, a new fuel option that after more than 15 years had finally demonstrated its technical, environmental, and pricing advantages to a skeptical and demanding power generation market.

Yet, its success was not to be. From the apogee of PDVSA’s published 2003 expansion plan to the shutting down of all production at yearend December 2006, Orimulsion was the target of an unprecedented domestic attack carried out through the public media by both the Minister of Energy and the PDVSA president. The final blow was for PDVSA to renege on its long-term supply commitments. The main strand of their argument ran as follows:

- “It is more profitable for the Venezuelan state to use its existing B-EHC reserves to produce traditional oil products such as blends or syncrude than to make Orimulsion because….”

- “The market pricing and fiscal returns of these are far superior to those of Orimulsion because….”

- “Orimulsion was indexed to coal so its price was kept to $7/bbl for its bitumen fraction, and the fiscal revenue was too low….”

- “Because there has never been bitumen in Venezuela, Orimulsion is no different from all other oil production, and this proves that….”

- “Orimulsion was invented by the previous energy authorities in Venezuela solely to discredit OPEC, devalue reserves in the Orinoco Oil Belt to the price of coal, and cheat the state of its proper due in fiscal payments.”

Inherited options

Current PDVSA authorities inherited two options for developing the Orinoco Oil Belt: a $14 billion investment in four upgraders that could transform some 610,000 b/d of B-EHC into 500,000 b/d of 16-32° crude; and more than 10 years invested in research and development of Orimulsion, with a capital investment of about $500 million in a 6-million-tonne production unit, a pipeline, and port facilities at Jose, which could transform some 70,000 b/d of bitumen.1

Both options presented problems for the new oil industry ideology:

- No production from the Orinoco Oil Belt was counted in Venezuela’s OPEC quota.

- A low royalty rate applied to the upgrading operations as an incentive for foreign investment and to Orimulsion because bitumen was used as feedstock.

- The majority of ownership in the four upgraders and in the new Chinese Orimulsion module was foreign.

- Lower tax rates applied to all of these companies.

- Fiscal returns were low until 1999 as a consequence of indexing the price of Orimulsion to coal.

By yearend 2006 none of the first four factors above applied. Maximizing fiscal returns to the sole owner of the oil reserves—the Venezuelan state—via royalties and income tax and the shoring up of OPEC to increase prices were fundamental to all decisions undertaken and changes made.

The change in the fifth condition, vital to the future of the Orimulsion business, also took place when contracts signed in 2003 indexed the price of Orimulsion to gas or oil with PDVSA approval. However the new contracts and their improved pricing formulas were to be totally ignored in the rush of official criticism that would ultimately lead to the closing of the business.

A school of red herrings

Against a conviction that the “old” PDVSA system had been designed expressly to circumvent and minimize fiscal obligations, it is necessary to answer the three main strands of criticism directed against Orimulsion:

1. Making bitumen fluid would subject the Orinoco Belt to OPEC quotas. Bernard Mommer, the ideologue behind the drive to close Orimulsion, charged: “PDVSA looked for other ways to manipulate the definition of crude oil subject to OPEC quotas: Increasing production of the extra heavy (heavier than water) crude of the Orinoco Belt—the largest reserves of its kind in the world—the company argued that Orinoco deposits, which are processed into a product called ‘Orimulsion,’ did not fall under the definition of crude oil.” [This assertion is technically correct, as the deposits do not constitute a liquid at normal temperatures.] “Therefore, PDVSA argued, the Orinoco Belt should be classified as ‘bitumen’ and, hence, not be subjected to OPEC quotas,” he wrote.2

By 2006, however, it was no longer politically correct to mention “the B word” in any document issued by PDVSA-MPPEP in reference to the Orinoco Oil Belt. Thus Mommer, now as Director of PDVSA, declared in a newspaper interview: “The reserves are classified according to their state within the reservoir and not their state on the surface… bitumen does not flow, it is a solid... there (in the reservoir) it flows, thus it is an extra heavy crude.”3

Nevertheless, prior to 2002 in Venezuela it was accepted that some 30% of the reserves in the Orinoco Oil Belt had an API gravity of 8.5° or less, and this fraction was classified according to international criteria as bitumen.

The use of bitumen as feedstock allowed Orimulsion to be excluded from the OPEC quota. No power plant could accept a long-term dependence on a single source fuel subject to unilateral supply interruptions. In addition, it competed against OPEC members’ natural gas, which was also outside of quota restrictions.

2. Orimulsion is not cost efficient. Actually it is a cheap fuel when indexed against gas or oil. During1992-2002 Orimulsion had to establish its technical, environmental, and even shipping credentials within a very competitive market. Pricing was established using coal as a reference, absorbing the cost of cleaning up emissions.

Fig. 1 shows how Orimulsion fares in theory vs. coal for newly built 750 Mw plants. All initial Orimulsion clients operated existing fuel oil-coal plants and profited from the market conditions to maintain Orimulsion pricing at or near the value for coal (cif Japan). This was the pricing scenario used to justify closing down the Orimulsion business.

However in 2003 the first major long-term contract was signed whereby Orimulsion pricing was established on the basis of the comparative economics of converting an existing fuel oil plant, including installation of a new flue gas desulfurization (FGD) unit vs. the cost of generation from a new gas turbine facility using imported gas.

The major advantage for Orimulsion under this new market option is the much lower capital cost of conversion (including an FGD) compared with building a new gas turbine facility. Now new contracts could be negotiated on the basis of the higher value gas index curves of Fig. 1. These initial contracts reached levels in the region of at least 50% of fuel oil prices. Taking into account that due to its heat content Orimulsion pricing has a ceiling at 70% of fuel oil pricing, this represented a major change in the pricing structure of the business.

Also in 2003 Bitor encouraged a US company in Guatemala to adapt the fuel for use in Wartsila generators. The technical success opened a completely new market segment for generating plants below 200 Mw where Orimulsion could compete at prices directly referenced to oil, a market segment where coal was not an option.

3. Merey 16 type blends are more profitable than Orimulsion. PDVSA and MPPEP have insisted that the Orimulsion business was never going to be as profitable as the use of B-EHC reserves for the preparation of Merey 16 blends (16-17º with 2.8% sulfur), which are sold at a higher price than Orimulsion and thus produce a higher fiscal revenue for the state.

The argument however presents a major flaw: PDVSA has never had the potential to increase its production levels of Merey 16 type blends to compensate for the total loss of revenues as a result of closing down the Orimulsion business.

Diego Gonzalez published very convincing figures to demonstrate the lack of sufficient Mesa light crude oil to implement any significant increase in PDVSA’s current production levels of Merey blends.4 Indirectly the same conclusion can be deduced from the fact that PDVSA and partners invested over $2.4 billion to transform 140,000 b/d of B-EHC into 120,000 b/d of a 16º syncrude with 3.3% sulfur, a product equivalent to a very sour Merey 16 blend. This investment makes no sense if they could have simply prepared more quantities of a sweeter Merey 16 blend using existing volumes of Mesa crude with available bitumen reserves.

Finally, import data published by the US Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (Form EIA 814) imparts significant evidence. Historically, nearly all of PDVSA’s exports of Merey 16 type blends has been to the US.5 Fig. 2 shows the historical data since 1992 when the Orimulsion business started. The closing of the Orimulsion business has not been compensated by a pro-rata increase in exports in the API gravity range of interest. In 2007 exports to the US in this range of crudes remained at basically the same level as in 2006.

The inability shown by PDVSA to increase its production of Merey 16 blends in the total absence of Orimulsion and in a raging bull market for oil prices, begs the question of whether the largest red herring of all has been the touting of higher priced blends as the excuse to close down the business.

In a September 2006 press release announcing the end of Orimulsion production, PDVSA stated: “...Once the nature of the feedstock was established as being the same as the reserves used as feedstock for the upgraders and for the preparation of blends, it was determined that either of these other options gave greater value to the extra heavy crude reserves than the Orimulsion option. Orimulsion production would now cede its place to the production of blends that would be improved in new upgrading facilities as they became available.”

Nearly 2 years after the PDVSA statement, there is no evidence of an increase in the production or export of such blends or of the construction of new upgrading facilities to process them.

Mommer himself once said: “This is also the opportunity to make clear why a policy of simply blending the extra heavy crude is not possible. The reason is that the blend enters a very limited market of refineries with deep conversion capacity. If this capacity is exceeded, the price of extra heavy crude would collapse.”

Therefore even Mommer’s contention that the production of Orimulsion instead of Merey 16 blends has generated an onerous opportunity cost for Venezuela ($290 million in 2002) rings hollow due to the lack of Mesa diluent and the absence of end markets that could have absorbed both the early production observed in Fig. 2 plus any hypothetical additional production of blends instead of Orimulsion.6

All these facts lead to the conclusion that PDVSA never had any new market alternative in the foreseeable future to compensate for the closing down of the Orimulsion business and the loss of $500 million/year in sales (2007 energy prices) for every 100,000 b/d Orimulsion module that ceased to exist.

Brave new world

Is this tale about the last days of Orimulsion simply a footnote in the history of energy, where PDVSA will be seen to have eliminated an interesting and growing segment of its export market, for reasons as yet unknown but which are certainly not the ones given in public by its authorities?

Or do emulsion type fuels such as Orimulsion represent a viable option in today’s energy-starved market that needs to be addressed seriously again as they can help alleviate the demand for energy and electric power in both the industrialized and developing world?

Bitumen and EHC reserves that are considered recoverable represent at this time around 1,000 billion bbl, with the two main deposits in Venezuela and Canada. A fuel along the lines of Orimulsion can bring part of these deposits into play in the power generation market within 3 years, at a fraction of the cost of installing new refineries, thus opening up sources of hydrocarbon energy supply at a most critical time.

The public track record of Orimulsion over some 15 years and the more than 60 million tonnes used around the world provide enough operating, transport, storage, and emission data to give a very solid starting point for a fresh look at this option. For major developing countries, which in the next decade will be the source both of an unstoppable energy demand and of increasing CO2 emissions, Orimulsion type fuels could represent a welcome choice between costly LNG and fuel oil options or the more probable sharp increase in the use of coal with 20% more CO2 emissions than Orimulsion.

Yet Orimulsion proved to be an inconvenient fuel, not only for PDVSA-MPPEP but also for energy suppliers, OPEC members, and environmental groups in the industrialized world. On the one hand it can make important inroads into traditional LNG markets and displace fuel oil in Wartsila type generators. On the other hand it forces a most necessary and critical environmental discussion to focus on technical and proven facts and not on perceptions, one that correctly places an Orimulsion type fuel in the context of tough energy choices that must be faced as developing countries inexorably inch forward toward a standard of living closer to that of the industrialized world.

Questions remain: Do the economics really make sense? Why should an effort be made to again develop the market for Orimulsion type fuels?

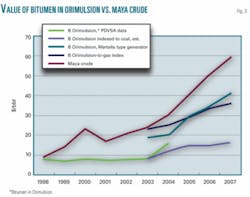

First, Orimulsion had proven by 2003 that a market demand existed for such fuels to generate power without having to lower its price to that of coal. Fig. 3 illustrates how the price of bitumen reserves marketed via an Orimulsion type fuel indexed to coal, to gas, or to oil compare with the price of Maya-Merey 16 crude. The lower solid black curve shows the pricing of the bitumen fraction in Orimulsion as reported by PDVSA.

For most of the period it followed the stable coal index, but in 2004, the last year PDVSA published Orimulsion pricing, the new pricing formulas kick in. Had the pricing followed strictly a coal index, it would have continued along the dotted line.

The marked deviation in 2004 is a direct result of higher prices linked to oil that were suddenly in effect. The next two curves reflect the pricing bitumen reserves can command for contracts where the fuel is used in Wartsila type generators or where it can compete against gas in converted fuel oil plants fitted with FGD.

The final curve, Maya-Merey 16, really belongs to another market, because at these prices neither crude can be used for power generation for most of the period covered.

Second, the market growth PDVSA initially projected for Orimulsion—to 300,000 b/d—was based on long-term fuel contracts. Orimulsion, like LNG, could only grow on the back of guaranteed customers as there was no spot market for this fuel. Thus by 2006 there was a certified market demand for enough Orimulsion to supply nearly 10 Gw in generation capacity.

Compared with coal and gas generation, this figure is a modest but significant incursion. Compared with other new energy sources, its impact is better judged by stating that the final withdrawal of Orimulsion from the energy market had the same impact as if all of the world’s geothermal or 13% of wind power generation had been eliminated, or in energy content as if 60% of ethanol for fuel production had suddenly disappeared from the market in 2006. The decision to foreclose such a relevant contributor to the world’s energy needs had to be justified on much more solid grounds than those here reviewed.

It is possible to tap quickly into bitumen reserves with low capital requirements and to obtain long-term contracts for power generation that value the bitumen fraction at $30-40/bbl at 2007 energy prices.

Any new phase in the saga of this type of fuel will require two incentives: a push from B-EHC reserves owners seeking faster and less capital intensive outlets for their underground assets before they are devalued by competition from other sources of energy and a pull from plant owners, retail and industrial customers, and government agencies, which will in the future be under strong pressure to present a lower-cost alternative to their increasingly vocal and critical client base.

It would be inexcusable to ignore that the option not only exists but has been tested and found attractive by important sectors of the power generation market around the world.

Bibliography

Contact the author for Annex material and bibliography.

References

- After 1999, under the guidance of President Hugo Chavez, a joint venture agreement was executed with China to build a second production module (6 million tonnes/year) at Jose to supply the power generation market in China. The $500 million module would be commissioned in 2006 and then shut down.

- Mommer, Bernard, Subversive Oil, Chap. 7, Ellner, Steve, and Hellinger, Daniel (eds.), Venezuelan Politics in the Chavez Era: Polarization and Social Conflict, Rienner, Lynne, November 2002.

- Mommer, Bernard, Aug. 15, 2004 interview in El Universal newspaper.

- Gonzalez, Diego, Petroleo YV, No. 25, 2006-07.

- The figures reported by Boue, The Internationalization program of Petroleos de Venezuela SA, Oxford Energy Institute, give a good example of this in the period 1999-2002.

- Mommer, Bernard, The Myth of Orimulsion, Venezuelan Ministry of Energy and Mines, and Middle East Economic Survey, 47:11, Mar.15, 2004. A real opportunity cost to Venezuela was PDVSA’s payment of $321 million just to New Brunswick Power for early termination of its Orimulsion supply contract.

The author

Saul Guerrero ([email protected]) is a private consultant on energy matters for Firewater Consulting in Caracas. He received his BSc in chemistry from Simon Bolivar University in Venezuela; a Diplome d’Ingenieur from EAHP in Strasbourg, France; and a PhD in physics from Bristol University in the UK. He gave lectures and performed research at Simon Bolivar University, then served for 15 years with Petroleos de Venezuela (Intevep, Pequiven, Bitor). Guerrero also served as director and executive vice-president of MC Bitor Ltd., in Tokyo during 1996-99 and was responsible for corporate supply and marketing of Orimulsion by Bitumenes Orinoco (Bitor) until early 2003.