Ship compliance will determine IMO 2020 market impact

Chris Cote

ESAI Energy LLC

Wakefield, Mass.

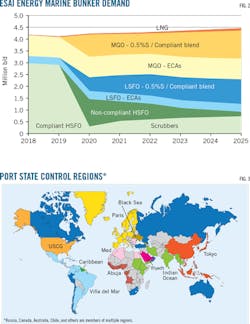

Regulations requiring reduced sulfur levels in marine fuels will hit oil markets in 2020, with around 1.5 million b/d of new compliant supply needed even after alternative fuels and non-compliance by some shippers are considered.

New International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules will most directly affect shipping fuels, a market of over 4 million b/d, the great majority of which is high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO). The 2020 requirements are not the first time the IMO has regulated sulfur emissions from ships. In 2012, the maximum level in the open oceans was lowered to 3.5% from 4.5%. Since 2015, ships that travel through Emission Control Areas (ECA)—coastal zones around Northwest Europe, the US, and the US Caribbean—have been required to use fuel with a maximum 0.1% sulfur content.

Most ships pass through ECA while on international trips, using a second tank to carry a small amount of compliant marine gas oil (MGO). But companies whose ships spend most of their time in these ECA have experienced sharp increases in their fuel costs.

Separately, several ports in China in 2016 began enforcing a 0.5% sulfur rule. China extended this zone to most of its coastline at the beginning of 2019. Taiwan has introduced the same rule at its ports this year, getting a jump on the global rule (Fig. 1).

The 2020 regulation goes much further than these rules, both in terms of sulfur content and the number of ships to which it applies. Reducing the sulfur content in fuel becomes exponentially more expensive the lower the content, and rather than applying to many ships part of the time, IMO 2020 will apply to all ships all of the time.

There are three basic paths to compliance. By 2020 all ships must do one of the following:

• Use a more expensive fuel with a sulfur content of 0.5%.

• Burn a high-sulfur fuel and run the emissions through an exhaust gas cleaning system, conventionally known as a scrubber.

• Use an alternative fuel like LNG, methanol, LPG, or even batteries.

Uncertainty surrounding fuel availability, quality, and price, as well as regulatory issues and costs related to alternative fuels, complicates this decision (Fig. 2).

Of course, a fourth option is to ignore the sulfur regulation and continue to burn HSFO. Perhaps the most important question in determining the impact of the 2020 regulation on fuel markets is whether there is an enforcement regime in place capable of keeping shippers in compliance.

Enforcement

The IMO is a body of the United Nations (UN) that regulates shipping. Annex VI of the organization’s marine pollution (MARPOL) rules regulates fuel quality issues relevant to air pollution, including sulfur emissions.

Countries choose to be members of the IMO. Once a MARPOL amendment has the approval of half of IMO’s members it is enacted, but member countries must still pass a law to implement the new rule domestically. Member countries are also responsible for enforcing IMO regulations for ships flying its flag. IMO 2020 limits were passed as part of a MARPOL Annex VI amendment in 2011 to regulate sulfur oxides (SOx) and countries passed laws to enact it, so no new legislation is required.

Countries can also be members of MARPOL as port states. Port states’ national maritime authorities are coordinated through regional groups. The largest are centered in Tokyo and Paris, but there are eleven in total, including the US Coast Guard (Fig. 3).

Port states enforce IMO rules under an inspection system called Port State Control, which was developed to assist flag states with the implementation of IMO rules. Port states can inspect ships, levy penalties including fines against them, and even detain them if they judge their noncompliance to be a danger to the ship itself, other ships, or the environment.

One of the key questions for IMO 2020 is fuel availability. Debated with last-minute drama at the October 2018 meeting of the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee was what happens if a ship’s captain judges the 0.5% compliant fuel available at port to be unsafe in some way. The compliant fuel is expected to be a blend of low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO) and MGO, a largely untried combination that could prove volatile if its flashpoint is too low, cause filter-damaging sedimentation if catalytic fines are too high, or present other unknown problems.

If a captain judges a port’s fuel to be unsafe, perhaps because it might not blend with the current fuel in the tank, but the fuel otherwise meets specification, should fines be imposed or a waiver allowed? If the chartering contract includes a clause that the ship must use compliant fuel, would the shipping company be breaking the contract in such a circumstance? Or does a lack of compliant-but-safe fuel allow for HSFO purchase? As of this writing, these questions, stemming from Regulation 18 in MARPOL Annex VI, remained unresolved, though shipping associations are drafting clauses for use in new contracts.

Even a uniform, global resolution to these questions, however, would not guarantee uniform enforcement by port states. Governed by domestic laws, most of which are vague by design to leave room for interpretation, enforcement of IMO rules by individual countries already varies a great deal in terms of inspection rates and the severity of penalties, including fines and detention.

For example, the US fine for illegally using HSFO in an ECA is $25,000/day. But in Belgium the penalty would be a one-time $6 million. Other port states pass news of the violation to the ship’s flag state and wait for it to levy a fine of its own. The port state also can look the other way, either out of good will or for a price.

Fig. 4 shows bunker demand by port and region.

Predicting compliance

A few guiding variables can improve our sense of what volume of fuel is likely to shift to compliance, and what volume over what time is likely to be noncompliant HSFO. We project that almost 75% of bunker fuel sold in 2020 will be compliant, either by meeting the sulfur specifications or by being used in a scrubber-equipped system. Of the non-compliant volume, some initially is likely to be covered by waivers due to fuel issues such as compatibility.

Compliance depends first on the availability of fuel. Refiners have the capacity to make sufficient compliant fuel, which in our analysis mainly will be a blend of MGO and LSFO, though some quantity of each will also be consumed directly. Even with a quarter of the fuel out of compliance, however, the price of compliant components, especially gasoil, will have to rise substantially for refiners to create enough compliant fuel.

Refiners will have to produce more than 1 million b/d of additional gasoil in 2020 compared with 2019 to satisfy bunker demand, as well as 500,000 b/d more LSFO. To do so, they will have to increase throughput significantly and also shift yields toward gasoil and divert vacuum gasoil from catalytic crackers. The large volumes of HSFO produced in doing so will weigh on margins and spur investment in secondary units.

Blending is likely to cause some supply-chain problems. But refiners, chasing higher diesel spreads to crude, will ensure the appropriate components are available. The higher diesel price will help address compliant marine fuel’s availability but will also widen the spread between compliant fuel and HSFO. This will have two consequences: it will shorten the payback period for the installation and use of scrubbers and incentivize more shipowners to cheat.

Enforcement generally will be stricter in busy ports than in those less visited. The majority of bunker fuel demand is met in relatively few countries. Singapore is the global bunkering hub, with ships stopping on their way through Asia. Mainland China and Hong Kong are two other refueling locations. Another key bunkering area is the Northwest Europe hub of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Antwerp. The main stop in the Middle East is the UAE port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman. In the US, Houston is a major bunkering port. Ships also stop in Panama to fill up. In these seven hubs alone, 2.5 million b/d of bunker fuel is sold, 60% of the global total.

Compliance should be highest in these ports because of their location and political motivations. Europe, especially northwest Europe, pushed hardest within the IMO for the new rule. China, including Hong Kong, has also advocated for the rule and signaled its desire for cleaner emissions by creating new local regulations. Most hubs will already have experience with enforcement ahead of the regulation, albeit at a smaller scale.

Singapore’s mandated mass-flow meters are likely to help ensure the fuel supplied there matches 2020 requirements, but the country carries out surprisingly few inspections compared with its neighbors and will have to deal with the extra complication of blending fuels from a large variety of import streams.

The US is an even more complex case. The administration of President Donald Trump led a last-minute effort to water down implementation at IMO’s October 2018 meeting, rightly concerned that the fuel specification change will cause a price spike in diesel ahead of the presidential election in November 2020.

This effort on the Trump administration’s part suggests the US might not comply fully, but even if that were the case, it would not be enough to change the global effect. And the country already has experience with ECAs, and its Coast Guard experience with enforcing matters of technology and logistics.

A larger exception is Fujairah, the Middle East’s bunkering hub. Fujairah is incentivized to comply at a much lower rate than other hubs. Much more of its traffic is sailing between low-complying ports, making the use of noncompliant HSFO much easier. Much of the traffic also will be flagged to Gulf states, which could give each other breaks on enforcement.

High-compliance ports’ ability to maintain compliance may be tested, at least initially, to the degree nearby ports have lax enforcement policies. For example, strict enforcement in Houston could push some business to ship-to-ship transfers off Mexico or storage hubs in the Caribbean, both relatively short trips away. This concern has its limitations, however, because most ports and countries, as well as shipping companies, care about how they are perceived.

For all involved, reputation matters. But this is especially true for public companies. The major oil companies and high-profile retailers will insist on compliant ships. The Singapore Maritime Authority has said it expects concerns regarding reputation, not fines, to be the main guarantor of compliance.

For many emerging economies, compliance is less likely, at least initially. Port capabilities and enforcement technologies are more limited, state influence over port behavior is lower, and bribes are more common. Some have already clearly voiced their opposition.

In May 2018 the Marine Environment Protection Committee agreed to ban ships from carrying HSFO in fuel tanks if the ship does not have a scrubber. But in October 2018 Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, and Russia challenged the decision. Even very low compliance in these countries will not weigh too heavily on the global weighted average, however, since most bunker fuel is sold in larger, more developed ports.

Other compliance options

Of course, a ship need not cheat to find a low-price fuel. In the months running up to January 2020, storage tanks will switch over to the blended compliant fuel. Ships will stop buying high sulfur fuel oil by fourth-quarter 2019 and, in 2020, HSFO bunker demand will fall by as much as half compared with 2019 levels.

Losing so much demand will widen HSFO’s discount sharply, to as much as $20/bbl below the price of crude. The price difference between a compliant fuel and HSFO is likely to be near $40/bbl in the first year of the regulation.

Scrubbers will cost $5-8 million/vessel to install and have a small operating cost. Even if the $40/bbl-spread drops to $30/bbl by 2022, a ship that uses 250 b/d (about 40 tons) and sails 250 days/year would pay back the scrubber’s entire cost in less than 2 years. A heavier, less efficient ship that uses more fuel per day would have an even faster payback period.

Such economics make scrubbers seem like an obvious option for most ships, especially heavy bulk carriers and tankers. Installation work is increasing rapidly, especially in those sectors, but concerns have caused ship owners to hedge options across their fleets. First, in some regions new regulations could be enacted that render scrubbers meaningless. China and Singapore have already indicated they will ban open-loop scrubbers—which dispense reacted sludge into the ocean—from their ports. Others may follow suit.

Global regulation of nitrous oxides (NOx) could change as well. Many ships do not have space to install both SOx and NOx scrubbers and could end up paying more or even having to uninstall their scrubber. Effective implementation of a carbon tax would also make use of petroleum fuels in general very costly.

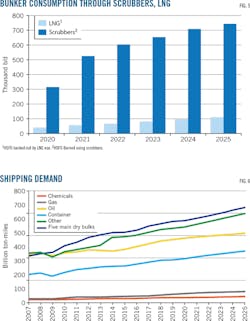

Scrubbers also are increasingly hard to get ahead of 2020. Alfa Laval, one of the largest manufacturers, declared in October 2018 that it was sold out into 2020. All in all, scrubbers will be relevant for just a small part of the compliant fuel balance, about 6% of total bunker fuel demand.

Another option is LNG, which is emerging rapidly as a marine fuel. But its growth comes atop a very small base. Retrofitting a ship to use LNG is costlier than installing a scrubber but has fuel-price advantages. Infrastructure limitations and a lack of appropriately equipped ships will keep LNG a niche option for the early part of IMO 2020 regulations, making up around 2% of bunker demand (Fig. 5).

With alternative options to comply making up 8% of bunker demand, and non-compliance making up just under 25%, almost 70% of the over 4 million b/d of bunker fuel will be a combination of gasoil and LSFO. Since about 800,000 b/d of gasoil and 300,000 b/d of LSFO is already consumed in ECAs, around 1.5 million b/d of new compliant fuel will need to enter the bunker market in 2020. It is this new demand that will bid up the price of diesel and cause refiners to raise throughput.

Global economy

The IMO 2020 rules are set to hit right as the global economy seems to be losing momentum. Interest rate hikes, oil price pressure in emerging economies, and asset bubbles in some markets have many expecting a significant economic slowdown by 2020. Fig. 6 shows demand for shipping by sector as of October 2018.

Slack economic demand would allow ships to slow down, using much less fuel. For example, a drop in dry bulk carrier trade of coal moving from Brazil to China, would reduce ton-miles significantly and cause an oversupply of ships on that route.

At the same time, while increased refinery throughput should boost crude tanker traffic, slowing product markets will take the pressure off refiners, though the change in location of LSFO demand could give a small boost to product tankers early on. The continuation or escalation of a trade war between the US and China could also slow container trade.

Any of these possibilities would reduce bunker demand. But even a fall of 200,000 b/d, like occurred during the 2008-09 recession, would nick, not upend, the volume of bunker fuel that will need to switch toward a cleaner, sweeter product.

The author

Chris Cote ([email protected]) is global fuel oil analyst at ESAI Energy LLC, an energy markets research and forecasting firm in Wakefield, Mass. ESAI provides comprehensive analysis of the global, regional, and national petroleum and alternative fuels markets, developed from a proprietary country-by-country fundamentals database dating back to 1978. Cote received his MPP (2016) from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and his BA (2009) from Tufts University, Medford, Mass.