WoodMac: Near current oil, gas investment levels enough to meet peak demand in 2030s

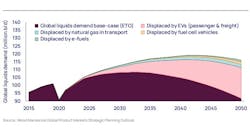

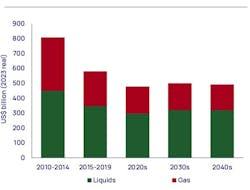

Peak oil and gas demand can be met in the 2030s without a substantial increase in current annual investment levels of $500 billion as efficiency gains, capital discipline, and low-cost oil will temper spending, according to a report from Wood Mackenzie.

Because spending currently stands around half of the $914 billion 2014 peak (in 2023 terms), the shortfall has led to concerns about underinvestment and an inevitable supply crunch.

“This was never Wood Mackenzie’s opinion” said Fraser McKay, head of upstream analysis for Wood Mackenzie. “Our long-held view has been that spending and supply would rise to meet recovering demand and that the upstream industry would not and could not reprise the ignominious years of ‘peak inefficiency’ during the early 2010s.”

Spending not much higher than the current run-rate can deliver the supply needed to meet demand through to its peak and beyond for three reasons: development of large, low-cost oil resources; capital discipline; and an improvement in investment efficiency, according to Wood Mackenzie.

“Conventional greenfield unit development costs have been slashed by 60% in 2023 terms” said McKay, adding “and US tight oil wells generate nearly three times more production today for the same unit of capital than in 2014. New technology, capital efficiency and modularization have been leveraged to powerful effect.”

Most of the industry’s oil and gas investment for the rest of this decade will target resources with the lowest cost, lowest emissions, and least risk, Wood Mackenzie said. Beyond that, new supply will become more expensive to develop. To meet demand, the oil and gas industry will depend increasingly on late-life reserves growth from legacy supply sources, higher-cost greenfield developments and as yet undiscovered volumes, it continued.

“Counterintuitively, the half-a-trillion run rate will need to be maintained beyond peak demand,” said McKay.

Alternative demand scenarios exist, each with different implications for future upstream investment. There are risks to the required investment showing up, Wood Mackenzie said. Efficiency and investment will evolve and the ‘required’ equilibrium is unlikely to play out, it continued.

While impacts of underinvestment would have consequences for the global economy, Wood Mackenzie believes that sustained investment imbalances are unlikely to persist.

“This cycle is certainly different”, concludes McKay. “Energy transition uncertainty adds a new layer of complexity and risk for upstream investors. But the oil market is literally and metaphorically liquid. Price signals, reinvestment rates and the actions of OPEC+ eventually bring demand and supply back into balance.”