Marcellus shale: a modern-day gold rush

Richard Capozza

Hiscock & Barclay LLP

Syracuse, NY

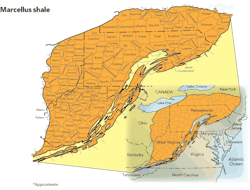

As a natural gas “gold rush” unfolds in Pennsylvania, producers and operators continue to sit on the sidelines just over the border, waiting for New York State to update and streamline its regulations for natural gas exploration and drilling in the Marcellus shale formation. As the largest gas shale formation in the United States, with an estimated 516 tcf of gas, the Marcellus shale presents one of the largest sources of domestically produced clean energy for an energy-starved Northeast.

Chesapeake partners with StatoilHydro in this Marcellus shale play operation.Photo courtesy of Chesapeake Energy Corp.

New York remains on the sidelines because of a bureaucratic regulatory process amid public fears and misperceptions over the potential impacts from horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, ranging from contamination of drinking water wells to explosions. Fracing allows operators to drill multiple subsurface lateral wells from one site and inject a high pressure mixture of water and drilling fluids to access the gas trapped in shale thousands of feet below the surface.

This process requires the use of huge volumes of water for each well, raising environmental concerns over withdrawal and disposal of fracing waters. These concerns, coupled with the regulatory morass in New York, have caused a near dead stop to what had appeared to be an energy and economic boom across the southern tier of the state. According to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) database, the agency received 36 permit applications for horizontal Marcellus shale wells as of July 1. In 2008, DEC received 13 applications for horizontal Marcellus shale wells. No permits have been issued.

And it does not look like there will be any significant improvement in New York’s regulatory logjam in the near future. Although the Marcellus shale was included in the New York State Asset Maximization Commission’s final report issued on June 1, the report included a recommendation that “…taking into account significant environmental considerations, the state should study the potential for new private investment in extracting natural gas in the Marcellus shale on state-owned lands, in addition to development on private lands.” (emphasis added). So it appears that New York State policymakers and regulators are not yet convinced of the economic benefits that the Marcellus shale can deliver but rather continue to focus time and effort on potential environmental concerns.

In contrast, neighboring Pennsylvania is overseeing a rush by dozens of natural gas companies eager to capitalize on Marcellus shale gas. As of June 26, Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has issued 768 Marcellus shale permits and 177 Marcellus wells were drilled. Since 2005, 431 Marcellus wells have been drilled in the state. Unlike New York, Pennsylvania has managed to incorporate the unique features of Marcellus drilling projects into its current permitting and environmental laws without becoming mired in a lengthy administrative process.

The delay in New York stems from environmental and safety concerns, even though operators have been efficiently and safely extracting natural gas in the state since the 19th century. Besides issuing permits, DEC is responsible for incorporating an environmental review into the permit process pursuant to the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA). In 1992, DEC satisfied SEQRA’s requirements by issuing a generic environmental impact statement (GEIS) that addressed the most common environmental impacts of oil and gas production and how they should be mitigated.

The 1992 GEIS expedited the environmental review and permitting process because companies who demonstrated that their project impacts and proposed mitigation were consistent with the GEIS could avoid the preparation of a costly and time consuming site specific environmental impact statement. Projects that conformed to the conditions and thresholds in the SGEIS could also generally avoid individual public hearings for each drilling application.

The permit process under the 1992 GEIS is working for non-Marcellus projects. DEC issued 742 new well permits in 2008 and, as of April 27, 2009, 328 permits this year, including some horizontal drilling projects. Only one permit was issued for a Marcellus (vertical) well.

In July 2008, New York Gov. David Patterson put the brakes on the state’s move towards becoming a major player in the Marcellus shale energy market when he ordered DEC to develop a supplemental GEIS (SGEIS) to account for the potential impacts of Marcellus shale projects. This began a long administrative review process which is still ongoing. DEC received more than 3,000 public comments on its SGEIS scoping document issued in October 2008. On February 6, DEC released the Final Scope, which outlined numerous issues the SGEIS would address including water use and quality impacts, fracing fluids, air quality effects, noise, aesthetic impacts, and community impacts.

Although completion of the draft SGEIS was originally slated for the spring of 2009, that deadline has come and passed with no indication by the agency when it will complete the process. DEC must still complete and issue the draft SGEIS, receive public comments, publish a final SGEIS, and issue a SEQRA Findings statement summarizing DEC’s conclusions. This process could take as long as 12 to 18 months from the date that the SGEIS is finally issued by DEC. Given the regulatory pace thus far and the public attention focused on the Marcellus shale in New York, it is not unrealistic to expect that the SGEIS process will not be completed until 2010 and even into 2011.

In the meantime, companies are left with the choice of waiting for the DEC to complete the SGEIS process or submitting to a lengthy and costly full environmental impact statement for each drilling application, which would also include a public hearing with no guarantee of timely approval. On Oct. 15, 2008, DEC Commissioner Alexander Grannis testified to the state legislature that he did not expect any applications to be processed until the final SGEIS is completed. This gives little hope for optimism that DEC will help alleviate the current situation.

Public concern and pressure have sidelined New York, with the biggest issue being water. New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP) in particular has expressed concern that drilling operations will compromise the city’s water supply and has requested that DEC consult it on all drilling projects within the city’s watershed. Although there has been no vote to date, there are bills before the state legislature which would ban all drilling within two miles of the city’s water supply infrastructure.

New York’s water concerns focus on source, quantity, and disposal. A major emphasis of the SGEIS is water withdrawals, as the fracing process can require more than one million gallons of water per well. Drilling opponents also claim that the fracing process will shatter confining layers of shale and allow underground contaminants to move into groundwater. The DEC has publicly recognized that, to date, there have been no known instances of groundwater contamination from horizontal drilling or fracing in the state. Notwithstanding, the SGEIS process will include evaluating whether to require private well sampling by operators and notification to DEC in the event of re-fracturing operations.

Disposal of fracing wastewater is another area of public concern. Opponents of drilling argue that fracing chemicals, which are designed to aid the drilling process, will contaminate drinking water sources. Currently, drilling wastes are regulated as industrial waste products and must be moved by a licensed transporter to an approved facility. Given the large volume of water and liquid drilling wastes, there is debate whether traditional disposal options can safely and effectively accommodate such large quantities.

Pennsylvania’s success in implementing a drilling program in the Marcellus shale, in contrast to New York’s difficulties, is illustrative. Pennsylvania does not have a state-wide environmental review process and has greater flexibility to act quickly, and has done so, to the benefit of industry.

Pennsylvania also has a long history and relationship with the oil and gas industry dating back to 1859. The state draws on a wealth of experience overseeing oil and gas operations, as an estimated 350,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled in the state. The state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) currently estimates that there are over 107,000 active wells in Pennsylvania. In contrast, New York currently has about 14,000 oil and natural gas wells.

To its credit, Pennsylvania has also devoted additional personnel and resources to the permitting process, and added an additional regional office to address the influx of applications. Using a newly implemented fee schedule, Pennsylvania has invested its increased revenues by hiring more staff to handle permit reviews and site inspections.

Most importantly, Pennsylvania addressed the new technology and challenges of Marcellus drilling by adapting its current regulatory processes rather than re-inventing the wheel. Without the delays seen in New York, Pennsylvania has developed a program with an emphasis on water management and protection, including coordination with area stakeholders and identification of water storage, treatment and disposal options. In March 2009, DEP centralized its review of Erosion and Sediment Control Plans associated with drilling, taking authority away from local conservation districts in the interest of uniformity. The expedited process is also intended to allow operators to obtain a permit in two weeks, rather than three or four months.

Back in New York, even when the SGEIS process is completed, it will not mean that the natural gas gold rush will restart, as numerous other regulatory and political hurdles stand in the way. If New York experiences the expected deluge of drilling applications, there is no guarantee that DEC has the staffing to process those applications on a timely basis.

In testimony before the New York state assembly in October 2008, Commissioner Grannis noted: “If a large number of permit requests for [Marcellus shale] drilling come in, we will certainly need additional staff in order to timely process the applications. If our staffing level remains static…it will take longer.” The DEC’s ability to staff up for the Marcellus shale is not likely to improve given New York’s current fiscal crisis and budgetary shortfalls.

As the New York state process drags on, the natural gas industry also faces increased scrutiny and organization by local governments trying to prepare for the Marcellus shale rush using their limited regulatory authority. New York state law delegates almost all authority over gas drilling to the DEC. Local governments have authority over town and county roads and the right to collect real property tax on natural gas equipment.

Despite their limited jurisdiction, towns are currently analyzing ways to require permits, bonding, and other restrictions on the heavy vehicles associated with the construction and operation of oil and gas wells. Local governments are also evaluating the adoption of general noise ordinances, which may have a disparate impact on natural gas companies. However, local governments are also looking to the Marcellus shale as an economic driver and as a source of new revenue to help plug municipal budget shortfalls.

Citizen and landowner groups are also taking advantage of the lull in activity in New York to become better organized and vocal. As of June, Cornell University’s Natural Gas Development Resource Center website lists 25 landowner and community groups and many more have sprung up across the southern tier. A brief survey of this list reveals objectives ranging from negotiating higher lease prices to assessing further potential community impacts to an outright ban on drilling.

Further state regulation outside the GEIS process is also possible. Fear of groundwater contamination has led the New York State legislature to consider requiring “green” fracing. One proposal calls for a ban on fracing solutions that contain toxic substances including diesel, benzene, toluene, xylene, ethibenzene, or any other substance deemed toxic by the DEC. Drillers could only use “natural and organic materials.” State and local agencies have also expressed concerns about the make-up of fracing fluid. DEC has taken the position that fracing fluid components must be disclosed to the state, but would not be subject to public release under the Freedom of Information Law.

The potential for the Marcellus shale to be an economic and energy boon for New York State is well recognized. As recently as the end of June, Hess Corp. finalized an agreement with over 700 landowners on the terms of new natural gas leases in two towns in the southern tier estimated to generate $66.5 million over 7.5 years, not including royalties. While such progress is reason for optimism, the question remains—will New York clear the political and regulatory hurdles to make the natural gas “gold rush” a reality, or will it remain on the sidelines while other states such as Pennsylvania reap the rewards?

About the author