Aberdeen: a global center of excellence for oil and gas

Part 2 — Life after forty: a second wind for the UKCS?

In the midst of global economic turmoil, Aberdeen’s oil and gas industry seems to have at least partially insulated it from the rest of the UK, if not the world. Even in an oil province of declining production and reserves, the city has remained a fertile hub for international expansion, M&A activities, and posted record cargo traffic at the airport and harbour. As though to emphasize this imperviousness, in the thick of the financial crisis, an unlikely vote of confidence was cast with the approval of Donald Trump’s plans to build a £1 billion golf resort just north of Aberdeen.

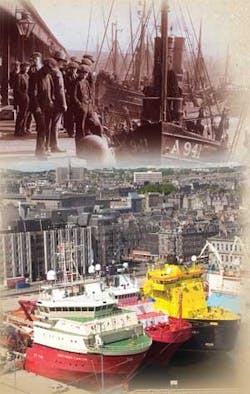

However, there is growing sentiment that it’s a matter of when, not if, Aberdeen will feel the pinch, and alongside declining oil prices, other circumstances aren’t lending much of a hand. Dramatic cost inflation, ageing infrastructure, and the looming prospect of decommissioning have only amplified calls for a renewed focus on innovation. Continued trends toward asset transfers from larger to independent players, and their reliance on easy finance, seem doubtful in light of a credit crunch. And even if these difficulties are overcome, there is still the matter of who, exactly — with painful shortages of skilled labour — will do the overcoming.

If cause for concern should be felt from the top down, it’s understandable Aberdeen has not yet felt the same impact as elsewhere. As Scotland’s First Minister Alex Salmond puts it, his “biggest concerns are not in the energy sector at all — they lie elsewhere in the economy.” Where exactly is uncertain, although the recent takeover of centuries-old Scottish stalwart HBOS by Lloyd’s TSB would certainly rank among the more prominent. To assuage worries around wildly swinging oil prices, the former Oil Economist with the Royal Bank of Scotland responsible for the 1980s development of the Royal Bank / BBC Oil Index draws a historical analogy. “To people who wonder about volatile oil prices, I remind them that when Colonel Drake discovered deep oil in Pennsylvania, the price went from $30 per barrel to about $0.20,” says Salmond, arguing that “the price of oil is volatile, and has always been volatile. People involved in hydrocarbons are accustomed to volatility, but the volatility experienced as of late is nothing compared to when deep oil was discovered.” Perhaps true, but then again, 150 years after Drake’s discovery, the role of oil bears a much different relationship to the world economy.

As a consequence of challenging externalities and the underlying reality of a declining resource, solidarity is needed at all levels of government, from the First Minister at Holyrood in Edinburgh all the way down. Lord Provost Peter Stephen represents the Queen in Aberdeen, and in turn the city throughout the world, as Aberdeen’s civic head — in partnership with political counterpart Councillor Kate Dean. As a board member of WECP (World Energy Cities Partnership), a grouping of 15 major world oil and gas centres, Stephen meets other civic heads, business leaders, and politicians, with the aim of creating and developing strong working relationships, which he says are a vital part of doing business, particularly on the international stage. The Lord Provost sums up the city’s image put forth in the economic arena: “Aberdeen has half a century of experience in the oil and gas sector. Initially expertise and education came from America; over time the city has developed its own repository of skills and expertise. Aberdeen’s expertise has been hard won in the hostile environment of the North Sea and is highly valued in oil and gas provinces throughout the World. We are very proud to boast that Aberdeen City & Shire is the Energy Capital of Europe.” As host of the WECP Annual General Meeting, Aberdeen will be showcasing itself to others in the partnership including Houston, Baku, Luanda, and North Sea neighbour Stavanger. Stephen is quick to point out that, as a city, Aberdeen has “a broader perspective than oil and gas alone and see ourselves as Europe’s Energy Capital. Over the past decade, alternative and renewable energy has become increasingly important in the wider scheme of things.” As proof of this importance, he offers that “Aberdeen hosts an alternative energy conference that is growing in size year on year; the 2009 conference holds a lot of promise. So we are very supportive of local efforts to diversify from hydrocarbon production.” These local efforts are indicated by the Aberdeen Renewable Energy Group’s work on several projects including joint investigations into windfarm feasibility, and establishing a new Professorship in Energy Futures supported by the University of Aberdeen, The Robert Gordon University and Aberdeen City Council.

However, for the time being, it will be hydrocarbon production and its related activities driving the economy forward, and there are still many challenges in the way of extracting the rest of the 25 billion barrels remaining under UK waters. These challenges are largely nothing new; after the industry went from $10 oil in 2000 to $60 oil in 2004, David Doig, Chief Executive of OPITO — The Oil & Gas Academy, explains “the industry realized that its behaviour was based on market demand but such a major change in product price had made a significant change to future plans and opportunities. Basically, this unpredicted and swift change had caught the industry with inappropriate levels of infrastructure, plant, and people. What the industry decided to do was realize its responsibility and take full ownership: to deal with the issues itself, and understand them much quicker, rather than relying on outside help.” Taking matters into its own hands, Doig continues in explaining one such manifestation. “At this point, what industry did was look to its traditional skills body called OPITO and morph it into a wider, bigger and stronger entity,” he says, referring to the entity he now heads, aimed to counter a history of “wait-and-see” policies in a low oil price environment. As Doig elaborates, “There was almost no investment made in workforce at $10 oil. And why would there be? It didn’t make business sense. In previous years, there were other industries in the UK — shipbuilding, mining — which don’t exist anymore. The oil and gas industry doesn’t have an issue of attraction. There’s a big long list of people trying to get in. But there’s an issue of skillsets, and transforming people with a given skillset to the ones needed.”

Once transformed, those people will be looking for work in robust, internationally competitive companies. Scottish Enterprise, a main economic development agency funded by the Scottish Government, is charged with doing just that. Brian Nixon, the organization’s Director of Energy, states its importance to the economy: “Energy, and the oil and gas sector in particular, is obviously a priority industry as it meets all the criteria: it has huge opportunities for growth domestically and internationally, a very strong supply chain, significant academic expertise in our Universities and a real will to work with us towards prosperity and growth.”

Moving these abstractions towards concrete actions, Scottish Enterprise has mapped the shape, size, and strength of supply chains in energy across various sectors and subsectors, finding not as many very large companies in the contracting sector as the organization would like, but rather seeing a small number of large and conversely a large number of small companies.

Nixon affirms that “Scottish Enterprise recognizes the need to work with these companies to help them become the next generation of major contracting companies: an ongoing program is currently working to identify companies that have the right technology and service expertise to meet the real market opportunities potential,” with the eventual aim of transforming such candidates into the next generation of majors like Wood Group, AMEC, and PSN.

Of course, to achieve this goal requires horizons beyond Scotland. According to Nixon, growth in international markets has been sustained over the last seven to eight years, and a third of the supply chain business is now conducted in international markets, accounting for approximately £4 billion annually. He notes “a large majority of our companies are now active internationally, and we support maximizing activity in the growing international market. We do so in a number of different ways,” including market intelligence, capex and opex projections in over 60 countries, all followed up by Scottish Development International, a partner organization offering in-country services to make the process as smooth as possible. Nixon gives the big picture: “To sum it up, our action starts by identifying which markets are of interest now and why. We then offer a range of information about the best market-entry strategy for each market and each country, to give companies the necessary support to develop sustainable long-term businesses.”

Aberdeen, hub for a spokeless world

Notwithstanding such helpful associations, and Aberdeen’s claim as Oil & Gas Capital of Europe — or for the more forward-thinking, Energy Capital of Europe — there is a warranted level of scepticism whether the city, despite years as an important centre of offshore and subsea technology, can remain an attractive hub for companies in need of increasing international expansion, especially as the region enters long-term decline.

However, even in shifting times, some companies have never had anything but an international reality. Garry Farquhar, Director/Dogsbody of Vector Supplies Limited, states his company is no stranger to foreign markets: “It’s a hard figure to put numbers on, but 60-70% of Vector’s business is overseas, and those figures have always remained fairly steady.” Strangely, and bucking the trend of increased internationalization, Farquhar points out how his company differs in having “a far greater international market than a local market in the early days. We set out to deliberately target the overseas locations simply because they were the ones suffering the most from the breakdown in the supply chains, and we started helping them straight away.” Vector’s help has come by representing three companies as main distributorships: American ball valve manufacturer Balon Valves, and two Dutch companies in De Wit for pressure gauges and instrumentation, and Resato specializing in high pressure technologies and equipment.

Although Farquhar admits Vector could operate anywhere with good transportation and logistics infrastructure, he cites an advantage of closer contact to large clients with significant city presence and worldwide decision-making as important success factors. However, even if opening up satellite offices would have its advantages, he notes “as with everything else, when you’re flat-out busy, as we currently are, these decisions never come quickly.”

Flat-out busy could certainly also describe Aubin, whose 300% growth in the past three years has been driven mostly outside Scotland, by the recent NOC trend of using local independent companies, with which Aubin counts itself in good stead. As Managing Director Patrick Collins explains, “Although the company is based in the North East of Scotland, about 75% of our business is elsewhere, predominantly in the Middle East.” Focused on cement and stimulation chemicals and subsea technologies, Collins explains Aubin supplies “specialist cement stimulation chemicals to local service companies in the Middle East rather than the big three major companies. It might seem strange that, being Aberdeen based, we sell most of our products there, but Aubin has been successful in developing that market.”

Even if the majority of business is done in the Middle East, Collins says there is an advantage to being located so far away: “Presenting chemicals coming from Europe and developed in the North Sea gives them validity and provides a level of comfort for our customers’ customers. Indeed, the North Sea is perceived as a technical area of expertise, therefore tools developed and proved in the North Sea have a distinct advantage when marketed in other parts of the world.”

On the subsea side, Collins anticipates that with increased commissioning and decommissioning activities in the UKCS, the company’s pipeline gels and pigging technologies will be further developed into a range of niche specialties and services to provide alternative solutions for insulation, sealing, or buoyancy applications. “In that respect our location helps us to enter our market, especially as there are not many other companies with chemistry skills operating in that sector. Aubin has been knocking on doors of course, but subsea companies are also coming to us looking for solutions that need a chemistry input,” he concludes.

Compared to Aubin, a relative newcomer to the international scene in Aberdeen is G.O.T. Director Warren Anderson says that “until two years ago, 90% of G.O.T.’s business was Aberdeen-based, either onshore or offshore. This included refineries down south, platforms in Yarmouth, Fife, Mosmorran, and customers as far north as Orkney. G.O.T. used to have customers as far away as Baku, although this was though a third-party. That market fell through, and G.O.T. decided to focus more on existing customers to see where we could grow with them.”

Through one such existing customer in Mobil UK, G.O.T piggybacked on a contract that led the firm down to the West African country of Angola. Speaking to the country’s specificity, Anderson explains: “Angola as a country is starting a project of nationalization to reinvest back in infrastructure, development, and education. Their stipulation for end-users like Chevron, Total, and Esso is that if they want to do business in Luanda, their suppliers must be on the ground operating on-site. Over the course of the last year, G.O.T. has been back and forth to Luanda looking at premises, staff, and going through a lengthy registration process.” The end result has been a current station of staff, offices, and approvals — all waiting on final documentation, which will see G.O.T. fully establish a satellite office in Luanda servicing up to one third of company turnover. Staying cautiously optimistic, Anderson admits that other than a Luandan outpost, “there are no plans for G.O.T. to grow geographically, and the company is quite comfortable managing what it has. A few years down the line, if Luanda is performing well and we manage to control both sides of the business, then expansion will be investigated.”

Founded in 2001, Petrowell recognized from day one that the only certainty was change. Identifying decades-old oilfield completion techniques not destined to forever remain the gold standard, Colin Smith and Paul Day, Managing Director and Business Development Director, explain that “Petrowell knew there was an opportunity for a small service provider with engineering excellence to get into the market and focus on new areas, like open-hole completion and remote operation completion, in the expanding subsea markets of West Africa and burgeoning business in the Middle East, so these were focus areas for Petrowell along with the UK.”

Elaborating on the technology focus, Petrowell’s expertise has also expanded to develop RFID technology with IP partner Marathon, a longstanding member of the North Sea community on both the Norwegian and UK sides. “Petrowell was looking for technology and services that would suit not just the low-cost land markets of the UK and the Middle East, but the expensive, more investment heavy markets like West Africa and the Gulf of Mexico as well as the North Sea,” note Smith and Day.

Taking a practical approach, Smith and Day emphasize their strategy’s core: “Petrowell wanted to concentrate on technology and equipment development with operators, and then provide a platform to the larger service companies where they could buy and license our technology and take it into a much larger global footprint.” This has reduced overhead requirements, and the no-nonsense approach has achieved its goal of attracting some of the world’s largest service companies like Weatherford.

A natural extension of this strategy is to avoid excesses whenever possible. Smith and Day say that “although Petrowell has one other international office in Baku, Azerbaijan, the aim is not to have multiple Petrowell-branded offices, but rather to adopt the most expedient and cost-effective method to support customers wherever they are in the world.” In a phrase certain to please its partners present and future, Smith and Day stress the company’s focus: “Petrowell’s money is better spent on products than infrastructure, and because infrastructure and supply chain management exist around the world, Petrowell wants to plug into that in a way beneficial to us and our customers.”

However, Petrowell could not afford to lack a physical presence in one particular major oil and gas center. Smith and Day note, “Petrowell had to be in Houston, because many operators run deepwater fields exclusively from there, regardless of their actual geographic location, and technology developments applicable on a global basis are handled out of Houston.” To the credit of their counterparts across the Atlantic, they describe the city as “a springboard to integrate Petrowell into the technology groups of the world’s biggest operators, the top four of which are based in the city, and also to demonstrate relationships with the service companies whereby if BP asks for Petrowell to be in Australia, we can say we will be there with Weatherford, for example. This approach has proven to be very successful.”

2 + 2 = 5

Although this minimalist approach may work for some, not all companies are as keen to keep such a large degree of their business outside. Exemplifying the Gestalt adage of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, some have decided to parlay this philosophy to maximize impact and reach across traditionally segregated business lines. While niche specialists can operate in silos, and take an appropriately narrow approach to their solutions, bigger companies — increasingly composed of these smaller niches themselves — are finding an advantage in hunting in packs.

Evolving out of necessity a decade ago from a diving company into ROVs, subsea inspection, and fields as diverse as US Navy nuclear submarine service and NASA space systems, Oceaneering International has created a virtuous cycle expanding its offerings from first client contact. Alan Gray, Global Integrity Manager, and Dave McKechnie, Deepwater Technical Solutions Eastern Hemisphere Manager, explain: “It’s crucial; when one of us appears, regardless of division, the client conversation may begin on the intended subject, but very quickly opens up to equipment, integration, ROVs, rope access, and it quickly expands from, for example, the need for a torque tool into corrosion awareness. There’s always an awareness of the bigger picture, and while there may be a standard client presentation, many clients may not be aware of the breadth of the offering.”

Of course, some areas may be more specialized than others, but that just increases the need for cross-communication. For example, Gray and McKechnie note that Oceaneering in Aberdeen is pursuing international contracts in Egypt, Azerbaijan, and Trinidad, even if they will never see 90% of revenues. Fortunately, this works both ways. They note, “Oceaneering is working closer now than ever and there is a reciprocal relationship between groups, so that even seemingly disparate interests can work in concert in a synergistic manner. An individual may be a small part of the whole system, but also be wired and connected into the right person for a particular meeting and particular question,” which means that when Oceaneering is called upon with a problem, it can put the relevant pieces together itself and come back with a solution. “It may be a matter of all divisions collaborating to solve a problem, but that’s the mechanism you can call on in Oceaneering,” conclude Gray and McKechnie.

While Oceaneering’s evolution has occurred over the last decade, Triton Group presents a less gradual example. Originating from current CEO Martin Anderson’s vision as former head of underwater vehicle specialists and Technip subsidiary Perry Slingsby Systems (PSS), Anderson explains the evolution since its genesis in mid-2003: “Throughout 2004 and 2005, PSS developed in a position to have a business plan going forward including some acquisitions and add-ons to balance the business. There were still some basic weaknesses of the company to be addressed. Irrespective of how the technology came together, PSS was still effectively selling products into the strategic capex market, in other words, selling assets to service companies who would then deliver their service. This is quite a cyclical market, so the basic weakness was the reliance on one particular product in one particular commercial model, and that market it sold into was quite cyclical, with long gaps between capex, assets, and replacement.”

Looking to smooth out this cycle, Anderson realized he would have to grow the business. Being constrained financially within Technip, Anderson took the company independent in February 2007 with private equity backing, creating Triton Group as the umbrella for the planned expansion. Having all the pieces in place, this newfound freedom enabled Triton to act quickly, signing heads of agreement just one week later to acquire SubAtlantic, filling a product gap to complement PSS hydraulic power with electric. In April of the same year came freelance offshore personnel business UKPS, and since that time, DPS and VisualSoft have joined the fold, simultaneously rounding out Triton’s offerings and expanding the market for their own services. With infrastructure developments in place covering Aberdeen, Houston, and Singapore, Martin sums up: “The last 18 months have been about putting building blocks in place. To use a Churchill phrase, ‘we’re at the end of the beginning.’”

No field left behind

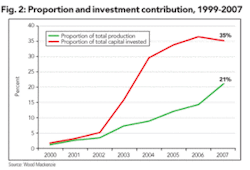

Not limited to wartime or aspiring subsea conglomerates, another beginning’s end can be found in the continued evolution of asset transfers. The trend of majors divesting assets to smaller, more dynamic companies is not news to anyone in the North Sea. Led by a slew of Canadian international oil companies, the UKCS now has a broad range of well-known names like Apache, Marathon, and Petro-Canada increasing life production and pushing reserves to their maximum. However, this trend has been taken to the next level, with specialized companies cropping up, armed with specific expertise in the region’s geology and sufficient cash to rescue underperforming or neglected assets — often smaller in size and poorly matched to the scale of their previous owners. Now, reserves otherwise characterized as marginal or stranded are seeing new life, with three of 15 asset deals in 2007 alone from new entrants, the cohort increasingly driving production and investment going forward.

One such company is Venture Production, whose Chief Executive Mike Wagstaff assesses the asset transfer situation: “There are a number of reasons why old discoveries in the North Sea became ‘stranded’: they are either not material, too remote, commercially complicated i.e. broken up into too many partners, too difficult due to infrastructure or can be unlocked by evolving technology. For example, many of Venture’s assets represent discoveries made 10-20 or more years ago. In late September, Venture brought onstream the Chestnut oil field discovered 27 years ago, and the Chiswick field brought onstream in 2007 was discovered in 1984. On Chiswick between that time and now, 10 field partners had come and gone, and none could make the field work.”

Clearly, however, with production of over 40,000 boepd, Venture succeeded where others failed. Wagstaff makes a strong case for the company’s presence in the region, noting “in terms of the operating environment, as a location to do business for an oil company, the UKCS is a pretty good place. In fact, for a company of Venture’s size and business model, it’s hard to think of anywhere else that would be better.” However, he acknowledges not everyone shares this rosy view. “Most people consider the North Sea mature, in terminal decline, expensive, highly regulated and bureaucratic, with high competition for opportunities — and if you do make any money, the taxman’s going to take it anyway. That’s the negative prejudice. On the other hand, while the opportunities may be smaller than in other less-mature basins, it’s just a fact of life, and the UKCS does have a number of things going for it,” and Wagstaff points to items on the plus side like infrastructure in the form of pipelines, platforms, and terminals facilitating tie-backs of discoveries or developments, alongside a ready market onshore to snap up any production. Add in a globally competitive taxation regime compared to neighbouring Norway or PSCs of Libya and Algeria in a higher oil price environment, with market responsiveness for tools needed to get the job done, and the picture of how Venture has grown from zero to FTSE 250 in under a decade becomes clear.

Although Venture is among the largest UK independents, there are many smaller companies at the table and plenty of opportunities to whet their appetites. Stewart Gibson, CEO of Sterling Resources, explains that at the company’s inception, it “had to be quite selective where to operate, because there were only two of us.” This was more out of necessity, given that according to Gibson, “when Sterling started, it was very much on a blank sheet, meaning no assets and no money.” From these humble beginnings Sterling has come a long way. With a deep knowledge of North Sea geology, Gibson explains the company “entered areas with proven hydrocarbons, so it wasn’t high risk exploration, but rather exploration within proven parameters,” and counter to conventional correlations between risk and reward, Gibson has frustrated actuaries worldwide with a spate of successful discoveries.

Both Breagh and Doina assets were drilled by majors over a decade ago, but “weren’t developed for various reasons, such as gas prices, contractual terms, or materiality, whereas a smaller company going into the same area can look at the situation with a different perspective,” says Gibson. This perspective has seen over 50% of Sterling’s drilled wells finding hydrocarbons, and Breagh testing at rates six times those achieved by the previous operator from the same reservoir, and as Gibson notes, “with changing gas price and current terms, something that had been stranded can be made to work.”

Fundamentally, what makes the assets work is the ease with which they can change hands. “There are major issues around the complexity of title transfer in the UK,” remarks David Sheach, Managing Partner of Stronachs, a law firm with an Aberdeen history stretching back over two centuries, who estimates that with the city’s evolution toward the oil and gas industry, his business evolved as well to 75-80% of commercial activity being linked in some way to the sector. “Unfortunately,” he says, “it’s not a nice, neat, registered title system, but layer upon layer of contract, and therefore the legal process involved in transferring ownership of assets can be quite complicated and time consuming. The fractional ownership of many fields can be quite a challenge as well, which is more a commercial than legal point, but obviously it impacts on the speed of the legal process.”

Sheach differentiates the UKCS from other areas: “Unlike regions with onshore licenses, where the capital costs are much less and therefore there may be a single company or two who buy, in the UK it’s not unusual to have four or more field owners, and the dynamics of getting all of them to go in the same direction at the same time can be interesting.”

One equally interesting case is Fairfield Energy, whose Chief Executive Mark McAllister explains how initially, it was a question of getting the sellers to go in the same direction. Harkening back to the halcyon days of 2005, McAllister explains “Fairfield had existed for a month, so for large companies like Shell, OMV, Exxon, and Statoil to come to terms with selling an asset of that scale to a company of our immaturity was not an easy task; it took a lot of work to persuade them,” including establishing a duty-holder relationship with AMEC and presenting a consortium of six international private equity financiers.

The tall order of skills shortages

Financing is not the only area in short supply. Indeed, lack of human capital is an oft-cited roadblock in the way of expansion. However, regardless of a new recessionary reality, the pressure to find the best and brightest is not likely to ease significantly. According to David Edwards, Chief Executive of the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board (ECITB), “the current skills base is just not big enough. The number of people needed for growth might soften, but we still need to replace the existing workforce.” The association, acting as a government body directly on the interface between government and industry, collects £5 of £18 million in annual training levies from the oil and gas industry, which it uses towards a system of grants which support training products and qualifications, designed in partnership with industry. Edwards continues, “Our core business is providing the right people with the right skill set, and by 2014, there will be a need to recruit, train, and retain in the area of 44,000 people across the skills range, of which 15-20% will be in the upstream oil and gas sector. This includes high-level engineering at the graduate level, as well as craft, technician, and operator level. ECITB now has the best-ever picture of industry needs and how to address them, and by and large the industry players have subscribed to it.”

Of course, addressing the full spectrum of industry needs is difficult on a limited budget, and even then, in niche cases requiring years of experience, no amount of training is likely to provide an immediate solution.

This is especially true for Maxoil Solutions, a firm created by bringing together experienced consultants with a wealth of hands-on and practical experience. Speaking to the search for qualified personnel, Wally Georgie and Mel Dow, Maxoil’s Principal Consultant and Director, note “they’re proving very difficult to find. Many of our existing employees were acquired via networking after having been in the industry for a number of years and establishing good contacts. Unlike other companies in Aberdeen who can more readily acquire people from different industries, Maxoil requires certain in-depth oil and gas process knowledge.”

However, Georgie and Dow have recently addressed the skills gap by taking on graduate engineers, fuelling a younger wave benefiting from older consultants and specialists. This bumper crop is likely to aid in the company’s ongoing international expansion, which has seen inroads to Norway, Gulf of Mexico, and Alaska. “In Houston for example, Maxoil’s plans in the medium term are to recruit people locally and bring them to Aberdeen for familiarization. They will then return as local Maxoil staff. Aberdeen is Maxoil’s training base and though there is good knowledge in all the spheres of the world, it is absolutely essential to have grounding in the fundamentals of the Maxoil philosophy and applying all the skills we’ve learned throughout our many years of offshore and onshore operating experience,” Georgie and Dow say. Maxoil has also diversified its talent base, reaching out to “technically orientated people to help with business development because at the end of the day, we need to build on our resources. There’s an important balance in having both technical understanding and capabilities for business development rather than solely depending on personnel recruitment and development because this is an important fit for Maxoil’s plans.”

One company helping to round out the knowledge of such technical experts is Adept Knowledge Management. Director Colin Balchin explains the reasons behind what made the company a preferred training provider for ECITB among many others: “The first thing that Adept has is knowledge: we know about project management, and managing big and small projects, because our people have done it. So our knowledge comes from practice, expertise, and also study, because we aren’t afraid to study and learn from others. Secondly, Adept has very good material and case studies, and tries to understand client needs and what they’re trying to do with the courses.” Understandably, knowledge and materials are necessary but not sufficient, which is why Balchin points to the last piece of the puzzle. “Thirdly, Adept staff take pride in being good teachers. All of the people who deliver the courses are really excellent at communicating, and do so with enthusiasm and humour, which is always appreciated,” Balchin remarks.

Perhaps ironically, Adept’s growth is itself limited by a lack of skilled people. “Adept’s overseas presence has to be limited by the quality and number of people who can successfully deliver the courses to our standard.” Being a smaller training firm, Adept can’t afford to adopt the shotgun approach of bigger competitors “because we are not organized to put out 50 different types of courses. We have ten or so courses, of which four are really the most popular. This also means that we can design and build courses to fit client needs and emphasis; and that’s what works well for us and our clients.”

Not everyone is feeling the talent pool pinch. When asked whether he has noticed an impact on employee attraction and retention in recent months, Neil Bruce, COO of AMEC Natural Resources, replies bluntly: “Not at all. The people who have suffered from resource shortages are the ones who haven’t had a long term investment program in people. If you are out in the market trying to hire people, and your only differentiator is paying them an extra dollar or pound an hour, you’re going to struggle.” Despite its size of nearly 11,000 individuals, AMEC has hardly struggled, increasing professional staff in 2007 by 15-16%, compared to the same figure the year before, and 12% in 2005. Bruce continues, noting that “Additionally, the company maintains a structured program in place to bring graduates through, with 200 technicians in our system at any point in time. Effectively, AMEC has an entire development program around human resources, and in constantly recruiting and developing its people, has found an increase in numbers by 15-16% annually very achievable.”

Bruce says that “for the people who want to go for the extra pound, we aren’t particularly bothered about them leaving. AMEC has people leaving, but has excellent retention rates, with employee turnover less than 5% across Natural Resources. If you provide people with training, development, and good interesting work, then you will keep the vast majority of your people motivated to stay with you. And the small amount interested in an extra dollar per hour can go get it elsewhere.”

Although not for directly financial reasons, Bibby Offshore’s CEO Howard Woodcock found he could keep a similar minority from leaving by bringing the business closer to its employees — literally. Woodcock explains “the company opened an office in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in early 2008 after recognizing that Tyneside, historically, has a lot of links with the subsea and offshore industry, and there are many people living and working in the area who have the kind of skills needed up here. The fact is that many of those people make a weekly commute to Aberdeen to work in the offshore industry, which is what gave us the inspiration to open an engineering facility in Newcastle.” Although still early days yet for this operation, he explains it “has both extended reach in terms of our resource pool whilst reducing carbon footprint in travel to and from, hopefully creating more satisfying and happier jobs and careers for our people.”

Leading by example, Woodcock himself is in his 16th year at Bibby, working his way up from deck cadet in the 1980s. Still, an available person with such experience is hard to come by. “The number of highly competent and qualified people available is limited, especially in the North East of Scotland, because there’s a lot of large calls from many companies, and choice in terms of employment at the moment. To overcome this, Bibby Offshore has had to think a little bit laterally and be innovative,” he concludes.

Do the safety dance

Innovation in the UKCS has not only been a product of business necessity, but sometimes a matter of life and death, as the community was recently reminded with 2008 marking the 20th anniversary of the world’s worst offshore oil disaster at the Piper Alpha production platform. Since that time, safety responsibilities transferred to the Health and Safety Executiv (HSE), which has set in place a system with mandatory approval of safety cases documenting management controls on every installation prior to use, and conducts reports on a continual basis into key industry interest areas. KP3, the HSE’s most recent report, involved an inspection of close to 100 offshore installations. Its findings acknowledged a lingering legacy of underinvestment, while identifying, as HSE Chair Judith Hackitt puts it, “the need for greater leadership, more good practice sharing and improved worker involvement.”

Iain Light, Oil & Gas Director of Lloyd’s Register, offers a snapshot of the current state of affairs: “There are competing objectives in terms of production, operations, and what really does needs to be taken care of. One of the challenges we have in the offshore business here in the North Sea is that many platforms and structures are well beyond their design life. The question arises of how operators and owners can reliably sweat their assets safely.”

Light stresses the difficulty many operators have justifying the necessary investments to do so under any circumstances: “In times of high oil prices, operations become so important at a time when you can afford to spend the money to improve the assets for the longer term. This is the dilemma when you have the money for the work but the pressure is on production. Now, with lower oil prices, they suddenly don't have any money to spend. The question arises: will we ever have the right amount of money to spend on the things we should be doing?” Light, explaining the nature of the group’s role in trying, says “the organization is very much about having an independent role, acting as an honest broker and company that is trusted by society, government, and operators.”

“Lloyd's Register's focus is going to be on getting a better balance with asset assurance issues, and understand not just the safety-critical issues, but also the business-critical issues,” Light articulates, a fact evidenced in work at 80% of the largest US refineries, where the Lloyd’s approach has enabled reductions in inspection and maintenance costs, improved environmental performance and safety records, and a better bottom line. In a message meant to clarify the traditionally UK-focused enterprise’s move towards true international dominance, the man bringing the organization forward at ‘the speed of Light’ says “Lloyd's Register wants to be very much positioned in that space of helping organizations strike the balance between their business, safety, and environmental agenda. We are about providing independent assurance helping our clients year by year improve the safety and sustainability of their contributions to the increasingly important energy supply chain.”

Improving safety in a more specific area of the value chain, Cosalt’s new Managing Director Calum Melville explains the company’s revised role after combining efforts with his former company GTC, noting “The products and services supplied as GTC and those offered by Cosalt, on the face of it, do not have a particular match, but they’re all safety-critical and driven by legislation. Looking at the range of products and services Cosalt now offers, this includes lifejackets, life rafts, lifeboat servicing, things that GTC historically didn’t do before.”

Broadening this range has meant a multifaceted approach to increasing safety. Citing an impressive case study, since Cosalt’s writing of a scheme of compliance for Shell, statistics have shown a 70% drop in incidents. Melville emphasizes the company’s three-pronged strategy that “for Cosalt, we are looking to drive safety in a number of ways: internally, through the equipment, and added value in supporting our clients.”

The oil and gas industry’s well-known conservatism and necessity for safety, extending to new technology adoption, perhaps explains Swellfix’s trajectory as a provider of innovative swellable elastomers. Despite a stellar failure-free performance record, CEO Arie Vliegenthart talks about the difficulties in swaying potential clients. “It takes a while to convince people to change their ways, especially with a maturing industry that may have been doing things one way for 40 years. It was not always an easy sell, entering an office with a “funny-looking” packer and convincing potential clients that it will replace or change the way they work. Having a good track record of course helped, and Shell’s technological reputation was like an approval stamp,” says Vliegenthart, referring to the company’s origins as a spin-off from the major.

However, the approval stamp was hardly a free ticket. “The first milestone, quite bluntly, was to get sales outside Shell. Having already run over 2,500 packers inside Shell, with a product suited to a few operations inside the company, Swellfix had the reputation inside, but not outside, Shell. Nobody knew Swellfix or the product, and it looks different than the competition,” Vliegenthart states, with the realistic assessment of his clients expectation that “In entering the market with a new technology to put in wells, there has to be a certain level of belief in the technology and the providing company’s structure and stability, because the company still has to be around when the well starts producing.”