Global expansion plans drive Chinese NOCs

Shanghai at night

Changes in the global political and economic environment and the desire to become integrated energy companies have led to an evolution in the Chinese NOCs' global expansion plans. The key driver, as directed by Beijing, for most of their partnerships and acquisition has not changed—material reserves and production positions, as well as the diversification of sources of supply.

At the same time, the Chinese NOCs are also looking for other things that they now need as they strive to become integrated energy companies: technology, political protection (from host countries who do not view Chinese companies favorably), and assets that help them to derive synergies across the value chain.

Claire Wong-Low, manager of the National Oil Company Strategies Service explains, "The success of the Chinese NOCs' international strategy will be measured by the volume growth of equity oil and gas from international activities, jobs that the NOCs can create overseas, spin-offs to the domestic economic sectors in the form of demand for related goods and services from Chinese companies, and the global stature that the Chinese NOCs attain. NOCs are not just after short-term financial returns to shareholders."

Global expansion efforts to date

Chinese NOCs, given Beijing's mandate to "go out," have, in the last decade, intensified efforts to seek reserves and production overseas. Their strategy basically has been to go where the reserves are, and many of these places also happened to be where IOCs have been prevented from entering.

Sudan, for example, was one of CNPC's early entry countries. Even today Sudan accounts for 36% of the company's total international production. Consequently, the NOCs have a globally dispersed portfolio of assets.

Chinese NOCs' overseas equity production contributes between ~12% (CNOOC) to ~20% (CNPC, Sinopec) of their total production with the domestic production still being dominant. Moving forward, contribution of NOCs' overseas equity oil production will increase as domestic oil production remains flat. However, there are few easy targets and access to resources has become much more competitive, between the NOCs and with IOCs. The Chinese NOCs have also evolved:

- in their economic power—China's economic growth has given them access to a large pool of financial resources

- in their strategy—increasingly wanting to be integrated across the value chain and

- in their awareness of political obstacles—the failed acquisition of Unocal was a lesson

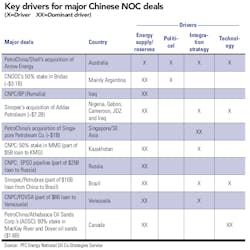

These create new opportunities and challenges for the NOCs' international strategy, which in turn shape their motivations for entering into relationships with other companies. PFC Energy's National Oil Company Strategies Service has identified four key drivers behind the Chinese NOCs' partnerships and acquisitions—political, technology, energy supply, and integration strategy.

Energy supply/reserves drivers

Energy supply and reserves drivers refer to factors that enable the Chinese NOCs to grow their oil and gas reserves base as well as diversify the energy supply sources. From all the deals listed in the table below, this is obviously the overriding driver for the Chinese NOCs.

In spite of the political risks involved, size still matters to the Chinese NOCs, especially CNPC, which is more interested in the bigger assets—Chinese NOCs have a large appetite for reserves and production and are willing to pay a premium for scarce resources. Consequently, CNPC wanted to get a piece of Iraq at all costs because, clearly, there are few opportunities that can match the scale of reserves there. In that same vein, CNOOC's stake in Argentina's Bridas Corporation as well as Sinopec's acquisition of Swiss-based Addax Petroleum all added immediate production and reserves to the NOCs.

Apart from the scale of energy reserves, diversification of energy supply routes is also critical. Low-Wong also points out that "CNPC's partnerships in Russia, Kazakhstan, and other parts of Central Asia provide an abundant source of oil and gas supply over land to China, diversifying away from energy supplies that have to pass through the Strait of Malacca (the dangerous, pirate-infested 550-mile narrow waterway separating peninsular Malaysia and the large Indonesian island of Sumatra)."

Political drivers

Political drivers refer to factors that help the Chinese NOCs overcome political opposition overseas or factors that help advance Beijing's political interests. The former has been dominant because Beijing is more concerned with its domestic energy security than with using oil to advance its political interests overseas.

The Chinese NOCs have the mandate to secure energy supplies and create employment in order to support China's economic development. Being a Chinese NOC increasingly has its disadvantages, particularly in OECD countries such as Canada, Australia, and the United States, but also in places where resource nationalism is strong and Chinese companies are viewed with suspicion. In most of these places, Chinese companies are often viewed by politicians as agents of the Chinese government and a threat to national energy security.

Consequently, NOCs are now more likely to seek partnerships that can help them overcome political barriers. This was true of CNPC's partnership with Shell to acquire Arrow Energy in Australia, as well as CNOOC's stake in Bridas, owned by the influential Bulgheroni family.

Integration strategy drivers

Integration strategy drivers refer to factors that help the Chinese NOCs to become integrated energy companies by building up parts of the value chain that bring synergies to their existing portfolios. The Chinese NOCs, using IOC giants such as ExxonMobil as an example, want to be integrated players and derive synergies from integration. This vision has led to an intensification in their quest for global assets.

Sinopec wants to build up its global upstream supply to feed to its domestic downstream refineries and is focusing on international upstream targets. (The Addax acquisition is an example.) CNPC on the other hand, wants to build up its global downstream business so as to derive synergies with its growing global upstream production—PetroChina's (CNPC subsidiary) acquisition of Singapore Petroleum Company, which will deepen its oil trading position with the addition of refining capacity, product storage, pipelines, and logistical assets in Singapore.

This also means that competition between NOCs will intensify as the NOCs have overlapping interests. There is some differentiation in risk appetite and types of assets that each NOC is looking for, which will help mitigate the competition, but it is far from a united approach towards overseas expansion. Beijing has, at times, stepped in as the final arbiter but it does not dictate the operations of the NOCs.

Technology drivers

Technology drivers refer to factors that help the Chinese NOCs build up technical capabilities. Historically, the Chinese NOCs were given a part of the domestic oil and gas value chain to focus on: CNPC focused on the upstream onshore sector, Sinopec focused on downstream, and CNOOC focused on the upstream offshore.

This suggests that the Chinese NOCs have had limited experience outside of their historical focus areas in China's domestic oil and gas sector, which is a problem for them as they go overseas. Given the scarcity of resources globally, the NOCs want to acquire capabilities to be involved in different oil and gas plays. Technology capabilities that Chinese NOCs want but lack include:

- LNG

- Upstream deepwater

- Unconventional resources (CBM, oil sands)

- Downstream and petrochemicals

Success of the Chinese NOCs

The success of the Chinese NOCs' international strategy will likely be measured by the volume growth of equity oil and gas from international activities, jobs that the NOCs can create overseas, spin-offs to the domestic economic sectors in the form of demand for related goods and services from Chinese companies, and the global stature that the Chinese NOCs attain. Their ability to be successful overseas will depend on their ability to acquire new skills and overcome the challenges in the global competitive landscape where they no longer have the monopoly they have in China as state-owned companies.

Information in this article was furnished by PFC Energy, a strategic energy advisory firm with offices in Beijing, Houston, Kuala Lumpur, Manama, Paris, and Washington, DC.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com