Rotational programs help attract, develop, and retain financial talent

Jim Johnson, Southwestern Energy, Houston

The severe cycles of the oil and gas industry have left a well-documented talent gap in our industry. While most literature and discussions on the topic deal with geological, engineering, and other technical personnel talent shortages, similar circumstances exist for the finance and accounting segments.

There is a great deal of competition from other industries for talented finance and accounting professionals and college graduates. This competition, coupled with the massive workforce reductions in previous cycles have caused a large segment of young and talented finance and accounting professionals to enter other industries.

These circumstances have created a need to find ways to quickly and effectively give those new to the industry quality experience in a short amount of time. Studies have shown that rotational programs are a valuable means to provide these experiences in a compressed time frame.

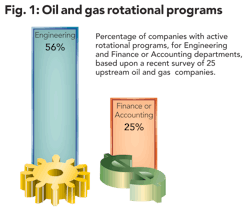

Formal finance and accounting rotational programs are currently utilized in many other industries with significant success. In a survey of 25 upstream oil and gas companies, 56% said they have rotational programs for engineering, but only 25% said that they currently have a rotational program available for their finance/accounting departments (see Figure 1).

The oil and gas industry remains woefully behind in using this effective tool to successfully attract, retain, and develop finance and accounting talent. These types of programs will accelerate development in order to help minimize the impact of the looming talent shortage.

Southwestern Energy has recognized the benefits of rotational programs and has worked hard to implement them in the accounting, finance, and treasury areas. Other firms in the industry that are considering implementing the rotational program should consider five critical success factors to an effective program:

Critical success factors

Executive management support and sponsorship

Support from the highest levels of management is essential to the success of the program. At Southwestern, the programs are supported by executive management, including both the CEO and CFO. Those who have been in the industry for some time can remember numerous "initiatives" that have been rolled out that are not truly valued by management. These initiatives tend to fade quickly and are generally ineffective.

In order to demonstrate the commitment to a rotational program, senior management should include it in the goal-setting process for the organization and its groups. A useful means of support would be to include aspects of the program in managers' bonus and performance evaluation structure. This motivates managers as well as demonstrates the importance of such a program. Without such a structure, managers will be tempted to cast the program aside in order to focus on their day-to-day tasks, which are often the tasks and responsibilities that comprise their bonus evaluation.

Clear objectives for the overall program

In order for any program to be successful, everyone must strive for the same outcome. On the surface this may seem simple. Obviously the purpose of the program is to accelerate the development of finance or accounting personnel in multiple areas of the company.

At Southwestern, when we attempted to define the overall objective of the program, it led to extensive debate and discussion. Broadly speaking, the discussion centered around the question of whether the program should be meant for a seasoned employee who had been identified as a potential manager or to take an inexperienced person and accelerate his or her development by giving that person a range of practice in various areas of the company.

There are numerous examples from other industries of both types of programs. General Electric, widely considered the gold standard for rotational programs, has developed a "Leadership Program" and in its summary states "Financial Management Program (FMP) is an intensive two-year, entry-level program."

One of the criteria for entering GE's program is that candidates have less than one year of external work experience. Genentech, a biotechnology company, takes a different approach. The company calls its program a "CFO Rotational Development Program." It specifically states that the program is for "high-potential future leaders" and requires at least three to five years' experience and demonstrated experience in effectively interacting with executives and senior leaders.

These are different goals that require different approaches. A program designed to accelerate the learning for an inexperienced individual would tend to have more focus on tasks and functions of various parts of an organization. In contrast, a program designed for experienced people identified as future leaders would tend to focus more on higher elevation concepts and incorporate projects whereby the rotator would have opportunities to lead, innovate, and make decisions that affect outcomes of major projects.

Clear objectives for each segment of the rotation need to be established and communicated

Just as it is important for everyone to strive for the same overall program objective, it is vital for everyone involved to clearly understand what the specific expected outcomes are. Clear objectives aid in determining the success of each part of the program. If the expected outcomes are not clear, it will not be possible to judge how well the program is working.

It is also crucial for the individual who is rotating to clearly understand what he or she is expected to gain from each area of the program. With this knowledge, the individual will be able to take the steps necessary to achieve assigned objectives. Absent a clear path, the person may be left to squander time by going in a different direction than was intended.

There can be any number of reasons why programs do not end up with clear objectives. In some cases there is a disconnect in expertise between the person responsible for developing the training and those who have proficiency in the area of training.

In many companies in our industry there is someone with either an HR or an educational background who is well versed in the concepts of training. The problem often arises from the fact that this person is likely not a subject matter expert (SME) for finance or accounting concepts and training. The individual responsible for training needs to enlist subject matter experts to develop the courses. The SME likely does not have the same in-depth background of training concepts and objective creation.

Another factor that influences the quality of objectives is that creating clear objectives can be very time consuming. The SME usually views the development of training programs as an extra task that is not part of his or her "real job."

Since many groups in our industry are run with limited resources to accomplish their day-to-day tasks, it is natural to push training development to the side, and when forced to "get something out the door," the person reverts to a hastily created set of broad concepts.

The level of clarity of the objective tends to correlate directly with the level of effort required to formulate the objective. In order to discuss this further, let's start with an example of what might be submitted as an objective about debt and equity markets.

1. Be familiar with debt and equity markets

Generally speaking, those involved with training or education as their career would likely not consider this an acceptable objective. In order to create a clear objective, individuals should ask themselves if, after reading the objective, they know exactly what it means. For example, the objective "Be familiar with debt and equity markets" is too generic to meet the standard as it leaves many open questions. Do you want them to execute a debt offering? Do you want them just to know that capital markets exist? Do you want them to be familiar with the company's debt structure? You get the idea.

With this standard in mind, a better example of a more robust objective might be:

1. The participant is expected to:

a. Determine trends in issuance spreads and underlying treasuries

b. Research relevant economic data and trends and peer issuance

c. Determine the impact on the company's capital structure of various issuance scenarios

d. Identify the mechanics of completing a transaction in each market

This example answers most, if not all, of the potential questions that arise from the first objective. After reading the second example, ask yourself, "Do I know exactly what the person is to do/know/understand/describe etc?" This objective makes it clear what the person needs to know and be able to execute.

Ensuring the opportunity for meaningful experience

The two main aspects of this point are ensuring that there are enough activities to use the individual's time efficiently and keep his or her job tasks meaningful.

Motivated employees become unhappy quickly if they have not been given enough activities to keep them engaged and active. Also, considering limited resources, it is not a responsible use of company resources to have an individual with little to do on a regular basis.

The problem usually stems from the fact that the person rotating into the groups is not part of the core group and generally needs guidance from others in the group to get started on projects and tasks. If the group is consumed with day-to-day activities, a great deal of time can pass before someone has (or makes) the time to work with the rotator and give some direction.

It is also vital that the tasks and activities that are distributed are meaningful. When resource or time constrained, the temptation is to use the rotator for administrative tasks. The initial plan may be to use them for these tasks for a short time and then move into more engaging activities. However, this situation can snowball very quickly and before you know it, the rotator has spent half of his or her time in the rotation doing administrative tasks. It is important to focus on tasks and projects that give a quality representation of what that particular area is about, as well as those that provide exposure to management for the rotator.

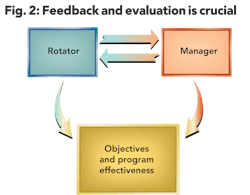

Frequent opportunities for formal multi-directional feedback

A great deal has been written about the value of multi-directional or "360 degree" feedback. This type of feedback is vital for a program like this. It is recommended, in broad terms, that the rotator give feedback on the following:

- How well did you accomplish the objectives?

- What did you think of the activities?

- How do you feel the manager did in managing you and the rotation?

It is also recommended that the manager give feedback to the rotator on the following:

- How well do you feel the rotator mastered the objectives?

- How effective do you feel the activities were?

A major benefit of frequent use of feedback is the opportunity to improve the program and the quality of the experience. This is especially important in the early stages of implementation when things are being tried for the first time. Another benefit is increased communication of expectations and perceptions regarding performance by all involved.

Conclusion

The finance and accounting functions are a vital part of the oil and gas industry. The approaching talent shortage in these functions, just as in technical areas, is real and requires innovation to successfully overcome it. A rotational development program is a proven and effective way to minimize the potential crisis.

Southwestern Energy's adherence to these critical success factors has helped the company develop and implement meaningful finance and accounting rotational development programs. The many intelligent and enterprising leaders in this industry should consider programs like these as a useful tool to solve our looming talent shortage challenge. OGFJ

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com