US energy and foreign direct investment: Is the foreign capital flow for oil and gas at risk?

Valerie Ellis and Billy Vigdor, Vinson & Elkins LLP Washington, DC

Government regulation is a way of life for the energy industry. Recently, however, a once-obscure regulator - the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) - has begun playing a much larger role on the energy stage.

Tasked with determining whether certain foreign direct investment in the United States poses a threat to national security, this interagency committee operated in relative obscurity prior to 9/11, typically reviewing transactions involving defense-related industries. However, a combination of political pressure and proposed legislative reforms may broaden the scope of CFIUS review to cover a significant portion of international-US energy deals.

What does this mean? At worst, if CFIUS finds that a deal may threaten national security, one or more member agencies may require the parties to alter the transaction materially. If there is no way to mitigate the national security concerns, the deal can be blocked. Even if all national security concerns can be addressed, CFIUS approval can delay the closing of a transaction. Despite these looming obstacles, the regulatory burden is not insurmountable and advanced preparation is the key to success.

History of CFIUS and energy

CFIUS’s power to regulate US foreign direct investment comes from delegated Presidential authority under the Exon-Florio Amendment to the Defense Production Act of 1950. The committee itself has been around since 1975, when it was first created as an advisory board to monitor foreign investment in the US and report to the President on the implications of such investment for the national interest.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan delegated to CFIUS his newly acquired authority under Exon-Florio to prevent foreign acquisitions that threatened the national security. Even with this substantial increase in powers, the committee operated under the radar throughout the 1980s and ‘90s.

Energy has traditionally been an area of some concern for CFIUS. In fact, one early controversial transaction reviewed by CFIUS was the 1981 acquisition of Santa Fe International Corp., a major drilling, exploration, and services company, by Kuwait Petroleum. Santa Fe owned some sensitive technology that had nuclear defense applications. At the time, CFIUS did not yet have any enforcement authority, so the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department was asked to hold up the merger.

Ultimately, the transaction was allowed to go forward after Santa Fe agreed to sell off its sensitive technology so that it would not be transferred to Kuwait Petroleum. While it is not difficult to see how nuclear technology and nuclear energy deals would be subject to CFIUS scrutiny, the relationship between oil and gas and national security is more tenuous.

On Sept. 11, 2001, the nation’s concept of “national security” was changed forever. In response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the government’s focus switched from its traditional examination of military targets and military assets, to a new emphasis on “critical infrastructure.”

In order to facilitate protection of critical infrastructure, the President issued a directive in 2003 requiring, among other things, oversight by the Department of Energy of critical infrastructure related to “energy, including the production refining, storage, and distribution of oil and gas.”

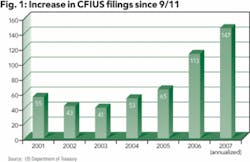

Additionally, since 9/11, CFIUS has been subject to increasing pressure by Congress to review foreign acquisitions of “critical infrastructure” for national security concerns. Since 9/11, the number of CFIUS filings per year has doubled, with significant growth projected for 2007 (See Figure 1). Nearly 20% of CFIUS filings in 2006 were energy-related - a trend that has continued thus far in 2007.

Perhaps the most high-profile energy acquisition where Congressional pressure was applied to CFIUS to stall the transaction was China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) offer to takeover Unocal Corp.

In mid-2005, CNOOC and Chevron engaged in a bidding contest for Unocal, with CNOOC emerging as the higher bidder. However, when Congress was alerted to the proposed acquisition, political pressure to block the deal began to mount, including the passage of a House of Representatives resolution asking the President to conduct a full CFIUS review of the transaction, because “oil and natural gas resources are strategic assets critical to national security and the Nation’s economic prosperity.”

Later testimony on Capitol Hill went so far as to suggest that foreign acquisition of oil assets by state-owned acquirers could be used to deliberately disrupt the US economy. Other allegations included concerns that some export controlled deep sea exploration technology used in oil and gas could be transferred. CNOOC ultimately withdrew its bid.

In 2006, media scrutiny of CFIUS intensified in response to a number of highly-politicized transactions, such as the acquisition of Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Co. (P&O) by Dubai Ports World. Calls for reform became commonplace.

Early this year, the 110th Congress answered with a new bill calling for sweeping reform of CFIUS, including the express construction of the term “national security” to include “homeland security” and “critical infrastructure.” The bill, which has strong bipartisan support and has already been passed by the House, is widely expected to be enacted into law in some form during the 110th Congress, and possibly by the end of this summer.

What does the proposed law require?

Much of the “reform” proposed by Congress actually involves a codification of current practice. The new law, if enacted, is expected to formalize the structure of CFIUS and codify its mandate to review investments for national security issues. While notification to CFIUS is likely to continue to be voluntary, reform would make it easier for any CFIUS member to initiate a review both of pending and past transactions. It is also possible that notification to CFIUS will be mandatory when the foreign investor is state-owned - an ownership structure not uncommon in the petroleum industry.

Most important for the industry, CFIUS reform is likely to specifically include “homeland security” and “critical infrastructure” in the definition of national security. Specific references to energy may also be included among the factors to be considered when evaluating a transaction’s impact on national security. Each of these changes is likely to increase the number of petroleum industry filings going forward.

How should energy companies prepare?

On Jan. 22, 2007, President George W. Bush in his State of the Union Address emphasized his growing concern with US “energy security.” The President’s approach to strengthening US energy security included limiting US dependence on imported oil and gas - in large part by opening up new regions of the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska to drilling.

For the US to be able to produce more oil and gas in the Gulf and Alaska, more inflows of capital will be required, and in a global environment, some of that capital typically would come from foreign investment. However, in light of the new push for stricter scrutiny of foreign investment in “critical infrastructure” such as oil and gas, energy companies selling interests, including non-operating interests, in their business should be prepared to clear a new regulatory hurdle before closing any transaction with a foreign investor.

Parties to a foreign investment in an oil and/or gas interest should be diligent in considering whether a CFIUS filing would be required.

Even under the current legislation, there are some who would say that all energy transactions must be submitted for review by CFIUS, because they deal with critical infrastructure. While the legislative reforms pending in Congress may eventually make that approach the most prudent one, for now it is reasonable for parties to ask themselves if there is a potential national security concern raised by their deal.

Certainly, any transfer of sensitive technology would make a filing advisable. For example, certain exploration technology, including seismic, could be considered too sensitive to pass into foreign hands. National security issues may also arise if the foreign acquirer operates in countries that are subject to US sanctions, such as Iran or Cuba. Additionally, the US government is showing an increased concern that countries like China and the United Arab Emirates present a possible diversion risk for export-controlled technology, so investors located in these countries should take care to ensure that all security issues are addressed.

Beyond these kinds of traditional concerns, parties should ask themselves if the asset being transferred, if compromised, would, in the words of the Patriot Act, “have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health, or safety.” For example, certain pipeline systems have been identified by the Department of Homeland Security as key critical assets.

An uncertain future

The irony of US government efforts to protect the nation’s energy security by keeping out foreign investors in domestic oil and gas springs from the fact that oil and gas represent fungible commodity products. Keeping investors from China, Russia, and elsewhere out of US E&P or US refineries only means that the capital flowing from these giants will be directed elsewhere in the world where natural resources are abundant. Congressional efforts to tighten down sanctions against foreign companies investing in Iran’s energy sector would seem to be at odds with any effort to discourage foreign companies investing in the United States.

At a time when the President has called for an increase in national oil reserves, some observers have questioned whether it is in the interest of national security to shut US exploration and production off to major capital sources and direct that capital into competing markets. Moreover, closing off investment in the US energy sector could lead some countries to retaliate by limiting the ability of US companies to invest in oil and gas production abroad. US energy security demands just the opposite.

DISCLAIMER: This article is intended for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or services. If legal advice is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. These materials represent the views of and summaries by the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Vinson & Elkins L.L.P. or of any of its other attorneys or clients. They are not guaranteed to be correct, complete, or current, and they are not intended to imply or establish standards of care applicable to any attorney in any particular circumstance.

About the authors

Valerie Ellis [[email protected]] is an associate in the Washington DC office of Vinson & Elkins whose practice focuses on a range of US laws and regulations that affect cross-border trade and investment, including customs, export controls, CFIUS, and trade remedies. Her sectoral experience includes oil and gas, alternative energy, steel, and heavy industry.

Billy Vigdor’s [[email protected]] principal area of practice is antitrust law, and he has extensive energy industry experience. A partner in V&E’s Washington DC office, he has been involved in merger reviews both inside and outside of the government in every phase of the oil industry, from E&P and midstream to the burner tip and the gas pump.