Merger endgames: How to prepare for the next structural stage of the oil and gas industry

Dennis Cassidy

Kristen Etheredge

Paul Weissgarber

A.T. Kearney Inc., Dallas

Many people think the era of mergers is over.

In fact, after the spate of late-1990s mergers that formed the supermajors (BP PLC-Amoco Corp.-ARCO-Burmah Castrol PLC, Exxon Corp.-Mobil Corp., Total SA-PetrofinaSA-Elf Aquitaine SA, and Chevron Corp.-Texaco Inc.), it almost seems that there's nobody left to merge with. The next industry trend will surely be something different.

But what? The merger trend caught many people by surprise. What will be the next structural adjustment to rock the industry? Where is it going to come from? And how can oil and gas companies be prepared?

Comprehensive research by A.T. Kearney shows that all industries go through four stages of consolidation. Across industries, companies at similar stages face similar challenges. Placing the oil and gas industry in the framework of this "Merger Endgame" suggests the key challenges that industry players will face in the coming 5 years.

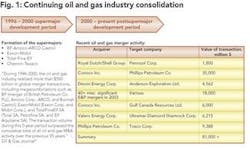

But first let's straighten out a misconception. As Fig. 1 shows, the merger era is hardly over. Industry consolidation continues.

Although most analysts found the total of $500 billion in merger activity during 1996-2000 a staggering figure, there is still significant deal flow—adding up only the major deals yields over $74 billion since that time.

True, many of these deals were smaller than the late-1990s megacombinations—but overall, the pace has slowed only slightly. The trend has continued, merely shifting to smaller and midsized players.

Why haven't the mergers stopped? Because the industry is still fragmented. Major players are still seeking to gain scale and cost advantage. Smaller players are either scrambling to catch up or submitting to the wisdom of playing with the big guys. The trend is not yet over.

Value of Endgames Curve

We can make such predictions because of our firm's study of a framework called the Merger Endgame. The complete results are contained in a book, Winning the Merger Endgame (McGraw-Hill, 2002), which is the result of research into mergers of over 25,000 listed companies in 24 major industries from 53 countries from 1988 to 2001.

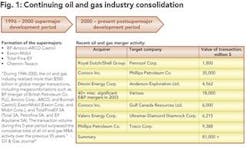

For a quick summary of the framework, see Fig. 2. As the figure shows, when degree and speed of concentration in an industry are charted, there emerges a pattern that spans about 25 years: an Endgames Curve. Once an industry is formed, it rides up the Endgames Curve and doesn't stop until it reaches the end.

This Endgames Curve forms an S shape that can be divided into four stages. Each stage has specific characteristics and results in specific outcomes. While some industries may spend more time in certain stages than others, they are all transformed in similar ways during consolidation.

Understanding the Endgames Curve enables a company to strengthen its consolidation strategies and facilitate merger integration. Why? Because for a merger to succeed, it matters less whether the companies are from the same country, are large vs. small, or even have complementary core businesses. What matters is their Endgames stage.

As Fig. 2 shows, the integrated oil and gas industry is currently in the middle of Stage 3 of the Endgames Curve. Its CR3 value (the market share of the three largest players) and Herschmann Herfindahl Index (another measure of industry concentration) place it above average but still far from the maximum.

In Stage 3, the Focus stage, successful players extend their core businesses, eliminate secondary businesses, and continue to aggressively pursue merger opportunities to outgrow the competition. The industry is still growing, though not as quickly or haphazardly as in Stage 1. Several major players have stepped forward via the megaconsolidations of Stage 2. But it remains to be seen how many of them will become the titans of industry that dominate Stage 4.

As Fig. 3 shows, each stage in the Merger Endgame is marked by differing characteristics, drivers, and results. Factors driving Stage 3 of the Merger Endgame include:

- Commoditization and world surplus of core commodities, resulting in margin pressure. As commodities, oil and gas are difficult for consumers to differentiate by brand, which creates fierce price competition.

- Enormous cost-containment pressures. As we will see shortly, the industry is doing remarkably well at slashing costs.

- Increasing capital expenditures requirements to sustain growth rates. At any stage, the challenge for companies is how they can continue to grow. But compared with earlier stages, industry maturity in Stages 3 and 4 requires increasing capital expenditures for ever-larger-scale projects.

The results separate the wheat from the chaff. Is it possible to remove costs while finding and investing in the projects that can bring continued growth? If so, a company will succeed. If not, it is a target for further consolidation.

Implications of Stage 3

The goal of Stage 3 is for a company to emerge as one of the small number of global industry powerhouses.

After the megadeals of Stage 2, the industry is populated by a few large companies that are starting to win the race toward industry consolidation. Again, this is not just an observation about the current oil marketplace; it's precisely the same situation that has faced dozens of different industries in the past.

The problem in Stage 3 is that strategic opportunities are increasingly hard to come by.

Because the industry has already been consolidated, megamergers are less and less of an option.

Because most companies have maximized their market penetration, it's also difficult to increase market share.

And because of the potential for a perceived oligopoly or monopoly market position, the industry may be subject to government regulation or scrutiny.

So what to do? Externally, a company should start shifting its focus to gaining economic return, rather than market share. It may want to harvest its competitive position by maximizing cash flow, protecting market position, and reacting to changes in technology or industry structure.

Rather than pursuing more mergers, a company may even want to peel off units that are outside its core competencies. Not only does it need to pursue what it does best, but if the company has a unit in an emerging market, that industry may be at Stage 1 of the Merger Endgame, and the unit can function better as a spinoff to move quickly through organic growth opportunities.

Internally, a company must focus on cost-cutting, especially on integrating the units from the megamergers made in late Stage 2 or early Stage 3. The danger, of course, is that the firm spends too much time on operational efficiencies and not enough time on satisfying its customers.

But in a world where only about half of all mergers lead to increased shareholder value, properly executing those mergers does have to be a priority.

Here, the news in the oil and gas industry is extremely good. As Fig. 4 shows, most major firms have been extremely successful in meeting or exceeding the target synergies of their mergers. Whether reducing costs or taking advantage of increased scale, their overperformance has been in some cases two or three times expectations. Driving down costs has not been a problem.

Furthermore, as Fig. 5 shows, this success has led to success in the stock market. Shareholder returns for all of the supermajors have outperformed the S&P 500 for the first 3 years of this century. On the whole, the oil industry has done well at Stage 3.

Growth imperative

But not every company will emerge from Stage 3. It's not just about cutting costs. To succeed, companies must reapply those savings to projects with the potential for high growth—and then those projects must deliver. Shareholder returns over the last 3 years suggest that some players are failing to expand their businesses at satisfactory levels.

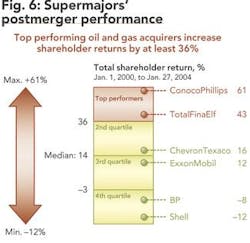

As Fig. 6 shows, BP and Royal Dutch/Shell Group are starting to fall behind, while TotalFina-

Elf SA and especially ConocoPhillips are outperforming their peers.

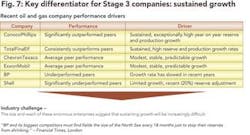

Why? A.T. Kearney analysis demonstrates that the key differentiator for Stage 3 companies is sustained growth. Growth drives valuation. Size alone is not enough; cost-cutting alone is not enough. A company must continue to grow (Fig. 7).

In the oil industry, that growth is best measured by reserve growth and production growth.

Charting reserve and production growth rates for the supermajors would yield a distribution similar to that in Fig. 6: ConocoPhillips exceptionally high, TotalFinaElf ahead of the pack, and BP and Shell slowing in their rate of growth.

What an incredible challenge: It's not enough to sell lots of oil, not enough to sell it cheaply and effectively. You also have to replace all of it, and more, at increasing rates.

In the 1970s the North Sea was considered the largest oil discovery of all time. Now, as the Financial Times of London reported, "BP and its biggest competitors must find fields the size of the North Sea every 18 months just to stop their reserves from shrinking."

Meeting that challenge takes almost exponential amounts of capital. Again, such challenges face almost every industry and drive merger dynamics.

Such capital expenditures require huge companies.

That's why there is the need to cut costs: to get the capital to invest in new production with the potential for high growth.

That's why a company must sell off portions of its portfolio: to get the capital to make the moves that impress Wall Street.

That's why the mergers are not yet over: because not everybody can keep coming up with capital at such a furious pace.

Five challenges for tomorrow

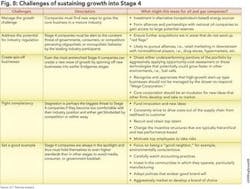

In the oil and gas industry, Stage 3 seems to be happening quite quickly. Companies have merged, they're cutting costs, they're seeking aggressive growth through large-scale, capital-intensive projects. So as we complete Stage 3 and move into Stage 4 of the Endgames Curve, what issues and challenges will occupy the industry?

Fig. 8 outlines five challenges and their potential impacts on oil and gas companies.

The first one is by far the most crucial: how to manage growth. Will new technologies help find and exploit new sources of oil (perhaps, for example, in the Arctic)? Will new partnerships with nationalized oil companies permit access to huge reserves that were not previously commercially viable (perhaps, for example, in Saudi Arabia or Iraq)? Will new investments in nonpetroleum-based energy sources provide alternative paths to exponential growth?

In a mature industry, such bold initiatives are the only ways to grow—and such growth is the only path to sustained success.

Second, as noted earlier, consolidated industries pose potential for government oversight. Especially in times of record profits, governments (and those who seek to influence them) may be overeager to uncover allegedly unfair competition.

In that sense, the era of megamergers may indeed be over; it's unlikely and probably unwise for huge oil companies to continue merging with each other.

But other techniques can come into play. Alliances, which provide many of the scale benefits of mergers, can reach nontraditional players.

For example, a global alliance with a retailer such as Wal-Mart would leverage the retailer's presence and expertise while likely avoiding regulatory attention.

Portfolio and asset decisions remain of vital importance. In an environment dominated by huge amounts of capital, deciding what to do with that capital makes a big difference. Nongrowth areas of the portfolio generate enormous opportunity costs: that capital should be used somewhere else. So it's necessary to divest those areas and get the cash.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the scale, it's impossible to be both a Stage 4 and a Stage 1 company. A company can be an incubator for new ideas, but when it comes to developing them and taking them to market, they need a quick-response, start-up type business. So it's wise to spin them off to create new growth through new applications of the Endgames Curve.

Which is not to say a company doesn't innovate. It always needs new ideas, new technologies, new approaches to driving costs out of the supply chain. Complacency is a huge problem for companies that are so big have so much money and technology and that they have lost that sense of start-up drive and struggle.

But as high-profile bankruptcies prove every year, no company is immune to competition; no company can sustain itself without risk.

By Stage 4, a company is not just one in a teeming mass of players, not just the unfolding of a single entrepreneur's vision. Together with a handful of other, mature companies, it has become the industry as a whole. Thus any single mistake threatens the entire industry. Reputation matters.

To enhance growth—for the industry and for your company within the industry—a company must set a good example.

Whether building brand will, investing in communities, protecting the environment, or bragging up your people-and-partnership skills, a company should seek to differentiate itself in positive ways.

Back when growth was the imperative, a company could compromise on other standards to achieve growth. Now the company's position is the imperative, and no compromise is allowed. ogfj

The authors

Dennis Cassidy is a principal in A.T. Kearney Inc.'s global energy practice and is based in Dallas. He has over 13 years of oil and gas industry experience with a primary focus in growth strategy development and operational and organizational improvements. Additional areas of expertise include postmerger integration, divestiture strategies, and supply-chain improvements. Cassidy is a graduate of Texas A&M University with an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering He has an MBA from Southern Methodist University.

Kristen Etheredge is a principal with A. T. Kearney based in its Dallas office. She has over seven years consulting in a breadth of industries, with a primary focus in the energy sector. Her areas of expertise include operational and process improvements, postmerger organizational transformation, and business process analysis and design. Etheredge is a graduate of Texas Lutheran University with an undergraduate degree in chemistry. She holds a PhD in chemistry from Rice University and an MBA from the University of Texas at Austin.

Paul Weissgarber leads A.T. Kearney's energy practice in the Americas and is based in Dallas. He has focused on strategy development and organizational improvement over his 22 years of experience in both the energy industry and management consulting. Most recently, Weissgarber has focused on helping energy companies in identifying and capturing value through the merger and acquisition process. He has an undergraduate degree in petroleum engineering from the University of Texas and an MBA from Southern Methodist University. Weissgarber is also a registered professional engineer.