Assessing the need for a better reserves reporting system

Albert Legault

University of Quebec in Montreal

Montreal

The recent panoply of revisions to previously released figures on proven reserves is bad news for the oil and industry.

The Royal Dutch/Shell Group announcement in January that it was downgrading by 20% the estimate of its proven reserves sent a shock wave throughout the world, and other oil companies since have followed suit.

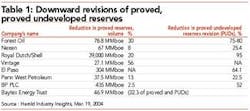

According to John S. Herold Inc., the downward revisions that followed have varied from 2.5% to 32.3% of the total proven reserves held by various oil companies and/or trust funds and, for cases where statistics are available, from 22.5% to 95% of proven undeveloped reserves (Table 1)

Of course, reserves revision is nothing new. But the scope and the magnitude of the process seem to indicate that there is something wrong with the system. The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) have developed a mandatory disclosure system which, since Dec. 31, 2003, forces oil companies to rely on outside independent evaluators to certify their proven reserves. This is in itself a welcome development. But no system can be foolproof, and reserve estimates will always leave a certain degree of uncertainty in the minds of administrators and/or stockholders.1

In the US, many are looking at the Canadian metrics now imposed on oil company disclosures to ensure good corporate governance. The US Securities and Exchange Commission, heaquartered in Washington, DC, has designed a number of rules over the years, many of them passed pursuant to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The most important ones require heightened standards of auditor independence and minimum professional standards for lawyers. The question for the future is whether the SEC will follow the Canadian model and ask for external independent reserves evaluators as well.

National Instrument 51-101

Canada's National Instrument 51-101 (Fig. 1), which lays down standards of disclosure for oil and gas activities, has been developed from the recommendations of the Alberta Securities Commission Taskforce, a 27-member group, with the close involvement of the CIM (Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy, & Petroleum, better known under the name The Petroleum Society).

The new directives replace the existing National Policy 2B, which is to be phased out by June 30, 2005, once the transition between the two systems is completed. The old policy did not include numerical probabilities of reserves recovery.

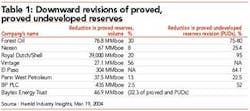

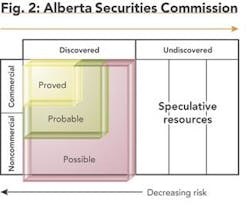

The Canadian standards include three categories of reserves: proven reserves (estimated with a high degree of certainty to be recoverable), probable reserves (less certain to be recovered than proved reserves), and possible reserves (less certain to be recovered than probable reserves) All three categories are subdivided into developed and undeveloped categories (Fig. 2, Table 2).2 3

In turn, the developed reserves are subdivided into producing reserves (they may be currently producing or, if shut-in, must previously have been on production, and the date of resumption of production must be known with reasonable certainty) and nonproducing reserves (previously in production but shut-in, with the date of resumption of production unkown). Reserves requiring an initial installation of compression are generally classifed as undeveloped.4 In addition, to be classified as proven reserves, the reservoir must have been penetrated by a wellbore and tested at an economic rate.5

In the past, the reserves booking and disclosure process relied almost exclusively on deterministic methods. Reserves estimation will continue to be dominated by deterministic estimates in the future, but Canadian exploration and production companies must file three reports, although these may be combined in a single document to be filed with CSA electronically on SEDAR (System for Electronic Documents Analysis and Retrieval)—the Canadian equivalent to the US EDGAR system (Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, & Retrieval System) (Fig. 1). The three reports must include Form 1, Form 2, and Form 3 filings :

- F1 being the statement of reserves data and other oil and gas information (essentially the company's statement of its proven and probable reserves).

- F2 being the report on reserves data by an independent qualified evaluator or auditor (which is an opinion about the company's reserves data).

- F3 being the report of management and directors on oil and gas disclosure (whereby the management confirms the F1 and F2 reports).

The primary classes of reserves must be included in the F1 report, but reporting of possible reserves is optional. For companies that follow the SEC/FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board) guidelines, constant prices and costs are used to estimate proven oil and gas reserves quantities and are reported on the last day of the company's financial year.6 The three categories of reserves, according to the new rules of the National Instrument 51-101, are now defined by specific probabilities of recovery. The targets must meet the following probabilities for the three classes of reserves: Proven > P90; Proven + Probable ≥ P50; and Proven + Probable + Possible ≥ 10.

Probabilistic methods are now often used worldwide for disclosure purposes. The numerical confidence levels referred to are minimum targets.

Probabilities are evaluated in total and on a country basis. If a company only operates in Canada, "then the corporate sum would be the highest level of evaluation."

On the other hand, if a company operates in several countries, "then the sum of each individual country would be considered the highest level7" (Fig. 1). The COGEH claims that the deterministic approach is comparable to the probabilistic method. The deterministic results, therefore, "represent a subset ot the values determined using the probabilistic method." Due to different treatments of aggregation (statistical aggregation vs. arithmetic summaries), Canada Oil & Gas Evaluation Handbook (COGEH) adds that estimates of proven reserves "should only be made at the level of aggregation for which estimates are intended to be equivalent." Hence, COGEH does not expect a material difference between aggregate results of estimates (reported reserves) prepared, "using deterministic or probabilistic methods or a combination of these." 8

SEC system

Bankers and shareholders hate uncertainty and risks, notes Jean Laherrère. They prefer "reserves with only one value, because a range confuses them." 9

That is why "the SEC refuses to report probable reserves and to trust the probabilistic approach." This is essentially true, but the US rules have not changed since 1978, at a time when geologists, by nature more optimistic than engineers, were regularly employed by oil companies to evaluate their reserves. The development of recent technologies such as 3D seismic surveys or improved recovery techniques allow the oil and gas companies to have a fairly good evaluation of their reservoirs' characteristics, without the need to go to the full and extensive route of formation tests.

The problem is further compounded by the US regulator's decision to bend the rules unilaterally for companies operating in the Gulf of Mexico. The new, implied SEC policy was set out in a letter by H. Roger Schwall, assistant director, corporate finance division, dated Apr. 15, 2004, and addressed to oil company finance directors. He suggested that seismic surveys are permitted, but he deliberately restricted the ruling to the US: "Please understand that we take this position only with respect to the determination of proved undeveloped reserves in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico and no other location." 10

This decision will further confound oil multinationals, which also are making huge deepwater investments off West Africa and elsewhere on the basis of 3D seismic surveys.

"In general, reserves estimates can vary for three major reasons. Or maybe five reasons. Although it might be four. Or even six. Everything depends on how you count," writes Ken Belson in the Mar. 12, 2004, International Herald Tribune.

The problem, however, is not so much how reserves are counted or proven, but how to ensure that they are reported in a mutually agreed fashion and accepted on a worldwide basis by all countries. The SEC does not accept probable reserves in an oil company's reporting system. This includes oil sands reserves, as the latter are considered as minerals extractions.11

The US is about the only country in the world obliging companies not to report probable reserves. This in itself is an anachronism.

Devising a better system

Any disclosure system must meet three criteria: It must be open, transparent, and credible.

It also should include the major partners involved in the controlling process. The primary mission of SEC is to protect investors and maintain the integrity of the securities market. Investors and banks should be included in the consultative process. Reserve auditors and the question of certifying their professional expertise also should be considered.

On the last point, many signs seem to indicate that the US is slowly coming around to the Canadian way of looking at things. Ron Harrell, chairman and CEO of Ryder Scott Co. LP, a Houston-based reservoir engineering consultancy, has publicly called for the need to certify E&P professionals in reserves estimations, perhaps in conjunction with the American Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers. The two institutions are intimately involved with reserves evaluation, as are their counterparts in Canada, and they should work together to develop a set of reserves-estimation best practices. The process is necessary not only because of Shell's and other oil and gas company reserves revisions but simply because evaluation has become more and more complex with the availability of new software packages and other tools.

The need for independent evaluators and the call for certification of evaluators—and for that purpose, decertification as well—is probably the first step necessary to instill a greater degree of confidence in the credibility and transparency of the system. There is also a need to look at nonconventional resources, such as coalbed methane, tight gas sands, and perhaps methane hydrates as well.

The need to involve banks and investors would also constitute an improvement in the system. J.J. Traynor, managing director of global oil and gas research at Deutsche Bank, in an open letter to the SEC in March, wrote: "The discrepancy between these guidelines and industrial reality, and the market climate following the Enron [Corp.] affair, is generating an unwarranted external push on the oil companies to underbook reserves and overamplify costs." 12

In all fairness to investors, this problem has to be adressed. The absence of data on probable reserves constitutes in itself a serious loss of information. Moreover, while Shell has been found guilty of identifying Gorgon reserves as proven reserves, this anomaly has not prevented ExxonMobil Corp. from showing a large number of resources in its annual statement, as there are no SEC rules on resources reporting. Reporting no reserves for Gorgon, notes Laherrère, "is misleading the shareholder."

Ideally, an international reserves reporting system regime should include the SEC, Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and perhaps the World Energy Council, because of its multienergy activities. There are wide discrepancies in reserves reporting, most particularly in the OPEC countries. This is obviously a long-term problem, but procedures should be developed to strengthen the credibility of any internationally agreed procedures on reserves reporting.

However, any internationally agreed system will not address the problem of enforcement, which for the time being remains exclusively in the hands of the SEC. This is another anomaly. It puts the US regulator in the unique position of having to enforce rules on a unilateral basis. All companies trading on the New York Stock Exchange are subject to established FASB oil and gas reporting standards.

The danger is that the oil multinationals will develop two sets of reporting systems, one for the US regulator and one in compliance with the national rules of the countries in which they operate. This will introduce more uncertainties into the system and will further complicate investors' choices.

As Commissioner Cynthia A Glassman said a year ago, the "SEC can implement rules to incent the good process, and we can enforce rules to disincent bad behavior, but we cannot legislate ethical behavior."

For the time being, reserves reporting is not an ethical problem but a consensus-building problem better left to certified independent experts and other actors directly involved in the process than to the vagaries of politics.

The author

Prof. Albert Legault holds a Canada Research Chair in international relations at the University of Quebec in Montreal. He is a member of the Royal Society of Canada and received the Order of Canada in 2000. Legault coauthored a recently published book on the strategic importance of oil among Russia, the US, and China entitled Le triangle Russie/États-Unis/Chine, Un seul lit pour trois? (Les Presses de l'Université Laval, Québec, 2004) and is the editor of a forthcoming book, Le Canada dans l'orbite américaine, to be published in September by the same university press. A recent publication on "Canada and Mexico in the North American Energy Market: Comparing apples and oranges?" is available in French at the following address: http://www.ameriques.uqam.ca.

1. A fact recognized by the Alberta Securities Commission, when it stated in 2000, not without humor, that reserves are like fish. The analogy goes like this. Proved Developed: The fish is in your boat. You have weighed him. You can smell him and you will eat him. Proved Undeveloped: The fish is on your hook in the water by the boat and you are ready to net him. You can tell how big he looks (they always look bigger in the water). Probable: There are fish in the lake. You may have caught some yesterday. You may even be able to see them but you have not caught any today. Possible: There is water in the lake. Some may have told you there are fish in the lake. You have your boat on the trailer but you may go to play golf instead. See http://www.oilpatchupdates.com/encyc.asp?view=1.

2. Largely inspired by the work of the Alberta Securities Commission in 2000.

3. The Calgary OilPatch defines the various categories of reserves in the following manner. Proved Reserves are reserves that can be estimated with a high degree of certainty to be recoverable under existing economic and operating conditions. Probable Reserves are reserves that have not been sufficiently explored and delineated to qualify as proved reserves. As such, probable reserves are less certain to be recoverable than proved reserves, and the additional expenditure they require to upgrade to proved reserves makes them less valuable on a per unit basis. Established Reserves equals Proved Reserves plus one half of Probable Reserves. This is a number commonly used by Canadian producers to account for the risk associated with proving up and developing probable reserves. Possible Reserves are reserves additional to proved and probable reserves that are less certain to be recovered than probable reserves.

4. See COGEH (Canadian Oil & Gas Evaluation Handbook), Vol. 2, published Apr. 28, 2004, by the SPEE (Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers, Calgary chapter), Sections 3.1.2-3.4 (available for comments on its web site).

5. Other considerations, such as the fiscal assumptions used and the necessity to not count reserves in areas prohibited by government regulations, also are included.

6. Some experts question the validity of this assumption, as the average price of the preceding year may be a better indicator of future revenue for any given oil and gas company.

7. Oil & Gas Reserves Disclosure White Paper, Schlumberger Ltd., October 2003, p. 3.

8. COGEH, pp. 4-13.

9. See Laherrère, Jean, Shell's reserves decline and SEC obsolete rules, Energy Politics, Feb. 27, 2004.

10. See http://www.sec.gov/divisions/ corpfin/guidance/oilgasltr0415 2004.htm.

11. The SEC rules do not take into account other oil and gas resources.

12. http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/story/0,3604,1175629,00.html.