Study sees Angola LNG project feasible but uncertain

A recently completed review of an LNG project in Angola by Wood Mackenzie Ltd., Edinburgh, has found the project holds great promise but remains threatened by, among other concerns, doubts about its gas sources and its ability to meet the projected start-up date.

As proposed by Sonangol EP (Angola's state oil company), ChevronTexaco Inc., ExxonMobil Corp., BP Exploration (Angola) Ltd., Statoil ASA, TotalFinaElf E&P Angola, and Norsk Hydro ASA, the project would use associated gas from offshore oil fields.

According to Wood Mackenzie, the consortium believes the development initially would consist of a 4 million tonne/year (tpy), $2 billion, single-train facility. A second train would be incorporated into the original design for possible later expansion.

The project was initiated in 1999 when Sonangol and Texaco signed a joint-planning agreement for development of Angola's gas reserves.

In its report, Wood Mackenzie assessed the participating consortium, development plan, gas reserves, proposed gas supply, project timing, and project economics. The report concluded that Angola LNG has significant potential. Given the early stage of development, however, some fundamental issues remain to be resolved.

Here are some of the findings:

- Angola has sufficient gas reserves to supply the proposed LNG plant.

- The project would benefit from a cheap gas supply. With the vast bulk of gas forecast to be delivered from associated oil production, the development cost required to produce the LNG feedstock would be low.

- There remain concerns over the source of gas for the plant.

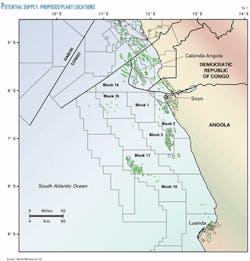

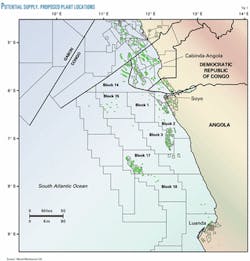

The original proposal suggested that supply would come from associated gas in the deepwater developments on offshore Blocks 15, 17, and 18 (Fig. 1), with some contingency supply from associated shallow water production in Blocks 1, 2, and 3. There now appears, however, to be significant movement towards using the shallow-water gas and developing stranded gas fields in Block 2 as part of the core gas supply.

Furthermore, the partners would have to overcome the not-insignificant engineering practicalities of crossing both the Congo Canyon to supply gas from Block 14 and the offshore Cabinda region.

- The project benefits from a strong partnership. The development consortium contains industry players with considerable LNG experience.

- The project benefits from strong government support. Sonangol has a 20% equity in the development and is committed to a successful project.

- Concerns exist regarding the project achieving its onstream target date of 2007. A recent decision to move the plant location from Luanda to Soyo highlights the very early stage at which the project remains. Such LNG projects tend to take about 3 years to complete, which implies construction must commence in 2004.

Much has still to be agreed upon, not least the fiscal terms governing the development and the signing of gas-sales agreements.

Progress on the project, says Wood Mackenzie, has been slow. And Sonangol recently announced some changes to the development plans (including the change in proposed plant location).

The project

All associated gas produced in Angola is the property of Sonangol, while the gas in stranded gas fields belongs to the Angolan government.

In 1997, Sonangol and (then) Texaco explored the possibilities of using the associated gas currently being flared offshore Angola to the south of the Congo River. The study found that enough gas reserves existed to supply an LNG plant.

The project, however, then suffered from delays, partly caused by the merger of Texaco with Chevron in 2001. The project received a significant boost in March 2002 when BP, TotalFinaElf, ExxonMobil, and Norsk Hydro joined the existing partners in the project.

The new consortium formed a joint venture company, Angola LNG Ltd., in which the participation is ChevronTexaco (32% and operator), Sonangol (20%), BP (12%), TotalFinaElf (12%), ExxonMobil (12%), and Norsk Hydro (12%).

Fig. 2 shows that almost all the major players in the deepwater Lower Congo basin are now part of the project.

Angola now has a no-flaring policy. As a result, says Wood Mackenzie, operators must find a use for associated gas produced from oil operations. That is why the bulk of the Angolan deepwater players are interested in the proposed project. They want to monetize the gas rather than focus on reinjection.

The project operator, ChevronTexaco, has an interest only in Block 14, which is not included in the base case supply source to the plant. The company does, however, operate Block 2, which was proposed in the original developed plan as a backup supply.

Wood Mackenzie feels Angola LNG benefits from an extremely strong financial partnership, with so many of the world's major companies active in the project.

Specifications

The plan, says Wood Mackenzie, is to build the first single-train plant with the second one to be added 2 years later. Space is to be incorporated into the design of the plant for a further two trains to be added later.

For a one-train development, says Wood Mackenzie, the project specification would require 750 MMcfd of feedstock. The gas would be transported to a shallow-water hub for limited processing before reaching the LNG plant.

Angola LNG is still in the planning stages, but frontend engineering and design will begin this year with final project go-ahead possible by 2004. Once development begins, the project will to take 36 months for completion.

Final investment decision for the project, says Wood Mackenzie, will occur by the end of 2003 or early 2004.

Development plan

Gas from the various fields would be connected to a central gathering hub (CGH) on Block 2 in 35 m of water near the Aturn field. The gathering hub would consist of a wellhead platform, riser platform, flare facilities, quarters, and utilities platform.

As production profiles change, says Wood Mackenzie, future gas processing and compression platforms would be required. The outgoing trunk line would have a pig launcher capable of supporting intelligent pigging operations. Nonassociated gas would be partially dehydrated and have any H2S removed prior to joining the associated gas in the trunk line.

The combined gas stream would be transported southeast from the CGH to the LNG plant via a 34 in., 160-mile (260-km) pipeline.

The gas would enter the plant and pass directly through a slug catcher and undergo further treatment before liquefaction. There would also be facilities for LPG and condensate processing.

A concrete gravity-based structure 200-300 m from shore would be used for LNG storage and loading. The structure would provide jetties for simultaneous loading of tankers. It would have a storage capacity of 220,000 cu m of LNG.

Original development plans, says Wood Mackenzie, called for gas liquefaction in Luanda (Fig. 1). However, recent reports from Sonangol indicate that Soyo is the preferred site.

In northern of Angola in an area affected by a recent civil war, Soyo is now being considered in an attempt to reduce development costs. It is unclear whether the final decision to move the plant has been agreed by all partners, says Wood Mackenzie, but the move further north certainly appears likely.

Gas supply, reserves

The main supply for Angola LNG could come from associated gas in the offshore Lower Congo basin fields from deepwater Blocks 15, 17, and 18. With the exception of Girassol on Block 17, which currently reinjects associated gas, no other projects are onstream.

Because associated gas as a main supply source can fluctuate with time as production profiles change, Wood Mackenzie says additional supplies would be made available from Blocks 1, 2, and 3. This gas would be used initially to compensate for shortfalls as more deepwater fields are brought onstream.

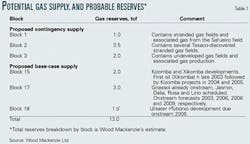

Wood Mackenzie says Angola LNG has released certified reserve estimates for Blocks 1, 2, 3, and 17. These blocks contain proven reserves of 4 tcf, proven plus probable reserves of 9.5 tcf, and proven, probable, and possible reserves of 26 tcf (Table 1). The gas reserves in the other blocks are Wood Mackenzie estimates.

Wood Mackenzie feels that 5-6 tcf of gas is required to supply one LNG train for 20 years. Therefore, from figures released by Angola LNG, it appears that the project has more than enough gas at its disposal for the initial train from only the certified reserves on Blocks 1, 2, 3, and 17.

Despite the fact that Angola undoubtedly has enough gas, Wood Mackenzie says the following major issues regarding supply remain:

- Early deepwater production will be heavily oil-focused. Associated gas volumes will only increase after the initial years of production.

- Some of the associated gas from the deepwater projects will be needed for injection to support the reserve-management plans. The volumes required are uncertain until the reservoirs are onstream and tested.

- Such are the economics in the deepwater projects that the fields will be developed to maximize the production of lean oil. This may result in fluctuations in the supply of gas.

- Progress in developing Angola's deepwater assets has been lethargic over the last 18 months. It has been speculated that Sonangol has been delaying deepwater oil field development until gas reserves have been properly evaluated and subsequent progress made on the LNG project. Delays could prove counter-productive, however, because delays in deepwater oil field projects will delay gas availability.

- The number of gas supply sources and relative distance from Soyo may actually increase development costs.

Many of the gas supply issues concern the deepwater fields, which were earmarked as the base-case supply source. Therefore, says Wood Mackenzie, there appears to be a movement towards using the shallow water fields in Blocks 1, 2, and 3 not as a contingent supply but as a primary supply source.

The proposed movement of the plant to the northern city of Soyo, nearer the shallow water fields, also suggests this change of emphasis towards the shallow-water fields.

With the concerns regarding gas supply and plant expansion earmarked for 2 years after initial production, it appears that Angola LNG is considering the potential for additional sources of gas supply from Block 14 and associated gas from the mature offshore Cabinda fields.

Timing of development

The LNG plant onstream date is critical, says Wood Mackenzie, given the highly competitive nature of the marketplace. Some western countries are facing declining gas reserves, and governments are looking for secure future gas supplies. Any project that comes onstream to coincide with the availability of new contracts and existing contract renewals would benefit.

Wood Mackenzie says the first train of the Angola LNG plant is scheduled to be complete in 2007. If it does, the plant would certainly be onstream no later than similar greenfield projects elsewhere in West Africa but still behind some brownfield expansion projects in Nigeria.

Furthermore, says Wood Mackenzie, Angola's recent development record shows that projects often suffer from development lag, although the delays associated with oil field development may not be applicable to an LNG project.

It has been suggested that part of the reason deepwater oil projects have suffered from delays may be associated with the lack of progress made on the LNG plant and Sonangol's desire for additional consideration of the gas reserves associated with the project.

Given the fact that there are a number of competing Atlantic basin LNG projects scheduled to be onstream between 2005 and 2008, says Wood Mackenzie, the cost of gas supply and securing markets will be key issues for Angola LNG. Project economics will be critical for each project to compete on such a competitive global market.

Cost of gas supply

With supply for Angola LNG coming predominantly from associated production from onstream fields, the gas would be cheap to produce. Wood Mackenzie feels some additional supply could come from the undeveloped gas fields in Block 2, but this gas would require some investment to produce. It is close to the hub, however, and would therefore save on transportation costs.

The main capital expenditure—with the exception of the plant—would be the cost of transporting the gas from the deepwater projects to the gathering hub in Block 2. The hub at the Atum field is about 100 miles (170 km) from the farthest supply source, Block 18, a distance not considered excessive for such projects.

Wood Mackenzie says Sonangol has stated that moving the plant from Luanda to Soyo would generate transportation savings of up to $200 million.

As mentioned earlier, all associated gas in Angola belongs to Sonangol. It is unclear at what price Sonangol plans to sell the gas to Angola LNG, but as is the case in other LNG projects, says Wood Mackenzie, it is likely to be for a nominal fee.

Angola LNG has the potential to benefit from a cheap gas supply, a factor that is very important in the economic viability of any LNG project.

Sales contracts

Sales contracts are perhaps ultimately the most important measure of whether an LNG project will be successful.

It can be argued that regardless of cost of development, cost of gas supply, development timing, and all the other important project considerations, it is the consortium that can secure the most sales contracts (at good prices) that will ultimately make its project viable.

Wood Mackenzie says Angola LNG has stated it intends to target markets in Europe, Latin America (chiefly Brazil), and the US. Geographically, however, Angola is at a disadvantage to some competitors because it is some distance from the markets it plans to target.

The Angola LNG project, says Wood Mackenzie, has no contracts in place. And it is extremely unlikely that development work on a $2-billion plant would begin until there are contracts for a significant proportion of the LNG. No sales contracts have been announced by any of the other greenfield projects in West Africa, and these consortia will be courting the same potential customers.

Another consideration, says Wood Mackenzie, is the increasing desire of Western governments to diversify their respective gas-supply sources. Spain has indicated that it will import no more than 60% of its gas from any one country. This stance is echoed elsewhere in the developed world because of continuing international unease. It is therefore possible that the various West African projects may be able to supply the same customers.

Despite little progress in development over the past 12 months, says Wood Mackenzie, Angola LNG still has many attractive aspects. The potential exists for Angolan LNG to be produced at a competitive price. Whether that happens may well be dictated by the fiscal terms Sonangol imposes on the development. With project sanction hoped for by the end of this year, progress needs to be made soon on fiscal terms and sales contracts.

This is a critical year for Angola LNG, says Wood Mackenzie. Recent doubts concerning the viability of the project have added additional questions as to whether the plant could be built to the already-revised onstream target date.

Sonangol recently stated that it remained too early to say when building work on the plant would begin, but that more information would be released early this year.