Antitrust strategies enhance merger approval likelihood

Companies contemplating a merger or acquisition are not alone as the oil and natural gas and oil field service industries continue to consolidate. Although some US mergers and acquisitions have quickly passed antitrust review by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), others have languished, bogged down in costly, time-consuming merger reviews, or have been subject to equally time-consuming and expensive divestitures. This article recommends strategies to speed the merger review and to avoid the antitrust minefield.

Merger wave types

There have been two major merger waves in the oil and gas industry during the last 2 decades. The first, which began in the early 1980s, involved financially driven, highly leveraged deals designed to unlock shareholder value. These transactions include Texaco Inc.'s acquisition of Getty Oil Co. and Chev- ron Corp.'s acquisition of Gulf Oil Co. Financial transactions such as these rarely raise significant antitrust issues.

The second merger wave began in the late 1990s, driven by efforts to reduce costs and increase operating efficiencies in an environment where oil prices were near a historical low. These transactions include mergers of British Petroleum Co. PLC (BP) with Amoco Production Co., Exxon Corp. with Mobil Corp., BP with ARCO (Atlantic Richfield Co.), and Chevron with Texaco.

Strategic mergers such as these between major competitors typically do raise significant antitrust concerns. More recently, independent operators such as Amerada Hess Corp., Tosco Corp., Valero Energy Corp., and Devon Energy Corp. have participated in the continuing consolidation in the energy industry.

As operators consolidate to wring costs and efficiencies out of a world oil market where they have little or no control over supply and price, oil field service companies are scrambling to meet their customers' demands for new technology, lower costs, broader geographic coverage, and more-comprehensive product offerings. To meet these customer demands, oil field service companies also are consolidating.

The Washington view

Predictably, the view from Washington, DC, is different. The antitrust authorities (FTC and DOJ), and particularly Congress, view the continuing consolidation in the energy industry with concern. Instead of seeing mergers as leading to efficiencies and cost reductions, Washington sees the consolidation as leading to higher energy prices. This is particularly true when an announced merger coincides with a spike in oil or gasoline prices. As a result, US antitrust agencies closely investigate oil and gas and oil field service mergers and acquisitions.

In a number of these transactions, the antitrust agencies have required competitive "fixes"—typically divestitures—as a condition for approving a merger. FTC has been particularly aggressive in mergers of operators, requiring significant divestitures in the area of producing properties (BP-ARCO), pipelines and refineries (Conoco Corp.-Phillips Petroleum Co. and Chevron-Texaco), and service stations (multiple transactions).

These divestitures have the potential to reduce the efficiencies and benefits the parties anticipate from a transaction. They also can be difficult and time-consuming to negotiate and implement. With the exception of the BP-ARCO transaction, FTC historically has found few problems with mergers on the exploration and production side of the business.

Geographic market definition is important in antitrust analysis. FTC typically views oil as a commodity in a world market. If significant numbers of LNG facilities are built in the US, FTC will be more likely to view natural gas as a commodity in a world market as well. FTC's antitrust concerns with mergers of operators historically have focused on refining, crude and refined products pipelines, and retail operations. FTC often sees narrow regional or even local markets for refined products or transportation. However, FTC has accepted that pipelines do compete with refineries.

Despite US Vice-Pres. Cheney's brush with DOJ in the Halliburton Co.-Dresser Industries acquisition in 1998 when he was CEO of Halliburton (OGJ Online, Apr. 29, 2000), don't expect significant changes in the antitrust enforcement of President George W. Bush's administration. Both FTC Chairman Tim Muris and then-Asst. Atty. Gen. Charles James stated that they don't plan substantial changes in antitrust enforcement policies. "Anyone who is expecting a major shift in enforcement policy is likely to be disappointed," stated James at a conference last summer.

That said, both Muris and now-Asst. Atty. Gen. Hewitt R. Pate are widely expected to require a firmer economic basis for their agencies' decisions, are more willing to consider the efficiencies created by a transaction, and are less likely to try to "push the envelope" in antitrust enforcement. That's good news for merging parties. Mergers of operators will continue to be reviewed at FTC, while DOJ will continue to review mergers in the oil field service industry.

The Brussels view

Despite the spat over the General Electric Co.-Honeywell Inc. transaction, which the European Union blocked on antitrust grounds after DOJ approved the transaction with a fairly minor divestiture, the EU typically has a more benign view of the consolidation in the energy and oil field service industries than the US. With the maturation of the North Sea, the EU's antitrust agency is more inclined than its US counterparts to view the market for energy and oil field services as worldwide in scope. Finally, energy policy is not as politically charged an issue in the EU as it is in the US.

Purpose of antitrust laws

The antitrust laws are designed to protect consumers and preserve competition. Somewhat ironically, given the rise of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and the limited oil and gas reserves of the major oil companies in the West, the Sherman Act and the antitrust laws were enacted in large part to break up the Standard Oil Trust at the turn of the century.

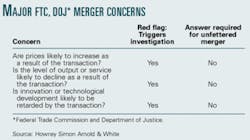

Today, FTC and DOJ share jurisdiction in enforcing the antitrust laws with respect to mergers and acquisitions. The role of FTC and DOJ in reviewing mergers and acquisitions is to determine whether a transaction is likely to raise competition issues. There are three fundamental questions the agencies seek to answer for each transaction (see table). A "yes" response to any of these questions raises red flags for the antitrust agencies.

Most mergers and acquisitions don't raise serious competitive issues. About 75% of the transactions in a typical year are approved by the agencies without significant investigation.

On the other hand, the recent strategic combinations among competitors that have characterized many of the oil and gas and oil field service transactions in the last couple of years are receiving substantial attention from the antitrust agencies. Strategic mergers and mergers with direct competitors are those most likely to raise significant antitrust issues. Fortunately, there are strategies that merging parties can employ to increase the odds that their transaction will survive antitrust review unscathed.

DOJ and FTC lawyers are prosecutors. They aren't searching for truth and the Holy Grail; they are looking to bring antitrust cases. Prosecutors make names for themselves by challenging transactions, not by approving them. Consequently, parties need to be prepared to argue the merits of their case effectively.

Effective strategies

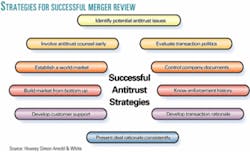

There are a number of strategies companies can employ to increase the odds of a successful merger review (see chart):

- Evaluate the politics of a potential transaction. Unlike mergers of operators, oil field service and equipment mergers aren't politically interesting. This is a huge advantage for oil field service companies because it allows DOJ to focus on the antitrust merits of a transaction without political pressure to simply "do something" whether it makes sense competitively or not. It is unusual for an oil field service transaction to draw Congressional scrutiny.

In contrast, it's a rare merger of majors or large independents that isn't met by calls from Congress for "close scrutiny" by the antitrust agencies. However, there is greater FTC tolerance today for industry concentration. Despite the political rhetoric, FTC to date has not blocked any of the "Big Oil" mergers, although it did require significant divestitures in several transactions. Had these transactions been attempted 10-20 years ago, it is quite possible that they would have been blocked.

While political pressure seldom is outcome-determinative, it does substantially lengthen and complicate the merger review process for operators. Moreover, antitrust "fixes" in oil and gas mergers—often divestitures of refineries, pipelines, or retail outlets—are typically thorny and protracted because of the complexity of separating vertically integrated assets.

For example, a major integrated oil field service company's lack of knowledge about an important DOJ position cost it substantial time and legal fees in a recent transaction. DOJ determined in the Baker Hughes Inc.-Teleco Oil Field Services Inc. transaction that MWD (measurement-while-drilling) is a separate product market that does not compete with wireline. And in 1998, in the Baker Hughes-Western Atlas Inc. merger in Houston, Baker Hughes's strength in MWD did not compete with Western Atlas's focus on wireline, and DOJ quickly approved the transaction.

Contrast that scenario with a recent oil field service transaction in which the parties fruitlessly argued to DOJ that MWD and wireline competed because they were trying to "expand" the market to minimize the MWD overlap between the companies. The result was a major DOJ investigation and a required divestiture of certain MWD assets. If counsel had had a better appreciation of DOJ's position on MWD and wireline, a different strategy could have been developed, and substantial time and legal fees could have been saved.

A world market

There are other important strategies:

- Establish a world market. DOJ and FTC prefer to establish that there are narrow geographic markets for products and services. Typically, this serves to limit the number of competitors and increase the merging parties' market shares, allowing DOJ or FTC to oppose the merger. FTC appears to concede that exploration and production markets are worldwide. In contrast, FTC often takes the position that markets for refined products and transportation (pipelines) are regional or even local. Parties need to be prepared to present facts to demonstrate that the markets for refined products or transportation are as broad as possible to reduce concentration levels. For example, FTC rarely has been concerned about refining acquisitions in the northeastern US because of the flow of refined petroleum products from the Gulf Coast and imports from Europe and the Caribbean.

In many oil field service mergers, however, the market may be truly global. For example, in the formation of WesternGeco in mid-2000 from the combination of the seismic fleets, data processing assets, surveys, and other assets of Schlumberger's Geco-Prakla unit with Baker Hughes's Western Geophysical unit (OGJ, June 12, 2000, p. 28), the parties were able to establish that there is a worldwide market for marine seismic services. This was absolutely essential to antitrust approval of the transaction. Had the market been limited to the Gulf of Mexico, as DOJ staff initially argued, DOJ would have probably blocked the merger.

This transaction paved the way for the Veritas DGC Inc.-Petroleum Geo-Services AS transaction in 2001 (OGJ Online, Nov. 27, 2001), which DOJ quickly approved without even opening an investigation. Similar arguments were successful in the Tidewater Inc.- Hornbeck Offshore Services Inc. (supply boats) transaction and the Transocean Offshore Inc.-Sedco Forex Offshore (offshore drilling) transaction.

But arguing a world market isn't limited to "floating" assets that can be rapidly redeployed. Imagine a transaction where the same equipment is used globally and tends to be manufactured in one or two locations by the parties and their competitors and is then shipped worldwide. We would be optimistic that the parties in such a transaction would prevail in establishing a world market, which is likely to increase the odds of antitrust approval of the transaction.

- Use customers effectively. DOJ and FTC need complaining customers to prevail in a merger challenge. It's highly effective to contact the customers before the agencies do, explain the transaction to them, and solicit customer support or neutrality. Why should customers support the transaction? There are a number of reasons. First, the company's customers may understand that it is trying to reduce costs and increase efficiency, which ultimately benefits them. Second, they may well be themselves consolidating. They may have no desire to "poison the well" and raise their profile with the antitrust authorities. Third, many of them are simply tired of Washington and the antitrust investigations of the oil and gas industry. Finally, customers and vendors alike have been through the wringer over the last 2 decades in a highly cyclical industry. There's a certain sense of camaraderie and a feeling that "we're in this together."

Customer support or neutrality can determine the outcome in a merger. For example, in the Baker Hughes-Oilfield Dynamics Inc. transaction (electrical submersible pumps), DOJ staff recommended to their superiors that the agency block the transaction. Baker Hughes and ODI were successful in gathering more than 100 customer statements expressing support for or neutrality about the transaction. The parties presented the customers' statements to DOJ management. Unwilling to litigate a case that it might lose because of customer support or neutrality, DOJ management rejected its staff's recommendation to block the merger, and the parties were able to close the transaction.

- Build the market from the bottom up. Most companies only follow and document their major competitors in their strategic plans and other internal documents. Particularly in transactions involving oil field services equipment or services on land, there are simply too many small regional players and independent "mom-and-pops" to track on a regular basis in a company's marketing and strategic plans. Consequently, company documents will imply that the market is far more concentrated than it actually is, allowing the government to use the parties' own documents to block a transaction.

While possibly involving a lengthy process, building the market from the ground up with the assistance of antitrust counsel and identifying all of the competitors in the market can be highly effective. Identifying additional competitors has two effects. It increases the number of players in the market, which helps to reduce competitive concerns, and it expands the market universe or size. This lowers the market shares of the merging parties and the concentration in the industry. Typically, this strategy is more effective in oil field service mergers than in mergers of operators because of the different nature of the industries. There often are numerous small players in the oil field services industry; this is rarely the case with operators when it comes to mergers.

The "bottoms up" strategy has been used effectively in the following transactions: Baker Hughes and Petrolite Corp. (production chemicals); Cooper Cameron Corp. and Ingram Cactus Co., (production valves and wellheads); Weatherford International Ltd. and Homco International Inc.(fishing and rental tools); and Smith International Inc., Wilson Industries Inc., and Continental Emsco Co. Ltd. (supply stores) . In each transaction, the parties were able to double or treble the size of the market initially estimated by the parties with comprehensive spreadsheets of all competitors and estimates of competitors' revenues.

- Take control of company documents. When moving into merger and acquisition mode, parties should take control of internal documents. This strategy applies equally to operators and oil field service companies. DOJ and FTC build their cases around internal company documents, which often are the lead government exhibits in an injunction hearing to block a merger. The Staples Inc.-Office Depot Inc. transaction challenged by FTC in the late 1990s is a classic example of internal company documents being used effectively by the agencies to block a deal.

Many companies, particularly those that haven't physically moved corporate offices, have documents and email stretching back for years, both onsite and in company archives. Companies routinely produce millions of pages of documents to DOJ or FTC in a merger investigation. At best, having company lawyers review and produce those documents for the government in a merger investigation eats up tremendous amounts of time and money. At worst, some outdated strategic plan or poorly drafted email string may be the government's lead exhibit against the merger.

Companies obviously can't legally dispose of documents during the pendency of a government investigation, as some companies belatedly learn. Companies have no obligation, however, to keep every report or memo ever written or every e-mail sent before an investigation begins. Just as one cleans house and discards accumulated treasures and outgrown kids' toys before putting a house on the market, companies should clean house and have all documents in order before going into merger and acquisition mode.

Strategy wrap-up

At the end of the day, there are no magic bullets or effective cookie-cutter approaches to get a transaction approved by the antitrust authorities. However, careful planning, hard work, creative thinking, transaction-specific strategies, and an encyclopedic knowledge of all prior enforcement efforts and investigations will substantially increase the odds of successfully and cost-effectively navigating the merger review process.

The authors

Sean F. Boland and Thomas D. Fina are partners in Howrey Simon Arnold & White LLP's antitrust practice in Washington, DC.

Howrey has represented numerous operators in oil and gas mergers, and Boland and Fina have shepherded more than 100 oil field service transactions through DOJ during the last 20 years.