Canadian oil and gas opportunities gather momentum off Atlantic and Pacific coasts

Canada's Offshore—1

With rising prices for oil and natural gas, coupled with declining North American production, the motivation to find new opportunities for oil and gas exploration and development off Canada's east and west coasts is high.

Opportunities for Canada's offshore oil and gas industry have been gathering momentum in recent months. Although both coasts have faced similar territorial disputes, concerns about potential environmental damage, and use conflicts with other ocean industries, the growth of the industry has differed sharply from one coast to the other.

The east coast industry is well developed following a number of significant discoveries since the mid-1960s and early 1970s. The west coast is absent of activity as a result of the federal and provincial moratorium on exploration and development.

Significant development in recent months suggest that Canada's offshore oil and gas industry could be hitting full stride on the east coast and possibly starting operations on the west coast within the next few years. Provincial and federal governments in both regions are working to resolve many of the regulatory, economic, and other issues that have plagued past attempts to develop these resources.

Even with some of the hurdles cleared, potential investors will still need to carefully navigate the minefield of provincial and federal environmental legislation that protects fisheries and the marine environment, as well as the complex royalty agreements with governments and others, including land claims by First Nations.

This article sets out the history and potential opportunities for offshore oil and gas development on Canada's east and west coasts and examines the key environmental regulatory processes governing the industry.

Atlantic Canada Background and Opportunities

In its latest annual estimate of oil and gas reserves, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers pegs known offshore reserves for Atlantic Canada at 800 million bbl and 2 tcf of gas. These estimates only include known reserves.

Much of the exploration and development action is happening off the coasts of two provinces: Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador.

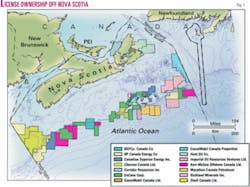

Nova Scotia drilled its first offshore well in 1967 and made a major discovery near Sable Island in 1971 (Fig. 1). As of Dec. 31, 2003, 124 wells had been drilled, with 22 yielding significant discoveries.

Nova Scotia's first offshore project, Cohasset-Panuke, began producing oil in 1992 and stopped in 1999 after producing 44 million bbl. That project is soon to be decommissioned. Still producing to this day is the Sable Project, which averages 550 MMcfd of gas.

Lately, Nova Scotia's offshore sector has slowed down. EnCana Corp. put on hold in late 2003 a scheduled new project, Deep Panuke, stating that it wanted to continue to look for a more cost-effective development method for the gas accumulation. More recently, Marathon Oil Corp. announced in September 2004 it was abandoning an $80 million test well off Nova Scotia's coast after failing to find gas in 4 years of exploration.

The province of Newfoundland and Labrador, for now, appears to have the greatest potential for new offshore exploration and development. So far, 129 exploration wells have been drilled, with 23 significant discoveries (Fig. 2). The Hibernia project, which includes Canada's federal government as a partner, averages 200,000 b/d of oil and has operated since 1997. The Terra Nova project began production in early 2002 and averages 130,000 b/d.

A third major project is expected to ramp up shortly. Husky Energy and Petro-Canada have announced plans to proceed with extracting White Rose field's 2.3 tcf of gas. As of July 2004, Husky announced that over 40 potential stakeholders have indicated an interest in contributing to the gas project, which should be in place by 2010. Meanwhile, about 250 million bbl of crude oil are also estimated to lie below White Rose, and the first oil should be brought to the surface in 2006.

Laurentian, other areas

All eyes lately have turned to another potentially rich area known as the Laurentian basin, which lies between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Laurentian area was the subject of major territorial disputes for over 30 years, first between Canada and France, which owns small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence south of Newfoundland and Labrador, and recently between the province of Newfoundland and Labrador and the province of Nova Scotia.

The International Court of Arbitration established the new boundary between Canada and France in 1992, and in April 2002, a federal arbitration tribunal established a new offshore boundary between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador. The federal and provincial governments involved are expected to sign a final agreement in coming months. According to the Geological Survey of Canada, this subbasin may hold 600-700 million bbl of oil and 8-9 tcf of gas.

In September 2004, three major oil companies—ConocoPhillips, Murphy Oil Corp., and BHP Billiton Petroleum (Americas) Inc.—announced they had begun 2D seismic surveys of the ocean floor in the Laurentian basin and were to start 3D surveys in 2005.

With billions of dollars invested in existing and upcoming projects, Canada's east coast oil and gas development sector has a very promising future.

British Columbia: Potential opportunities

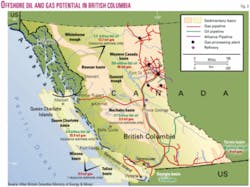

British Columbia has four key basins offshore: Queen Charlotte, Georgia, Winona, and Tofino.

The two major regions where untapped reserves are anticipated include the Queen Charlotte basin and the Winona-Tofino basins (Fig. 3). Both have little evidence of significant discoveries due to the fact the moratorium banned all exploration.

The Geological Survey of Canada, however, has estimated a resource of 9.8 billion bbl of oil and 25.9 tcf of gas for the Queen Charlotte basin. For the Winona-Tofino basins, the potential is estimated at 9.4 tcf of gas. These regions are similar in potential to the mature Cook Inlet oil and gas fields in Alaska.

British Columbia's offshore regions have been a no-go zone for all oil and gas activities since 1972, when the provincial and federal governments imposed the moratorium because of concerns about potential environmental disasters and interference with commercial fishery operations.

It is interesting to note that the governments considered lifting the moratorium in the mid-1980s but did not do so after 1989's oil spill from the Exxon Valdez tanker heightened fears about the development of an offshore oil and gas industry.

The ban on offshore oil and gas activity continues in place. Recently, however, with the decline in the fisheries, a more robust environmental regulatory system in place, and a safe offshore oil and gas industry off the east coast, there has been renewed interest to examine the moratorium at both the provincial and federal levels.

In 2002, a British Columbia-appointed Scientific Review Panel concluded there is no scientific justification for retaining the moratorium on oil and gas exploration off British Columbia. The panel made 15 recommendations for the province to consider before lifting the moratorium, including: establishing a comprehensive set of baseline marine information, ensuring a properly resourced regulatory and management regime is in place, and ensuring the effective participation of First Nations and coastal communities.

The BC government has already started to implement some of these recommendations by assembling an Offshore Oil & Gas Team to begin the process of securing the support of local communities, First Nations, and the federal government. The stated objective of the province is to have an environmentally sound offshore oil and gas industry up and running by 2010.

The federal government has also recently re-examined the moratorium question, having commenced three review processes in 2003: a Science, a Public and an Aboriginal ("First Nations") Engagement in respect of only the Queen Charlotte basin.

In February 2004, the federal Science Panel produced a report drawing a similar conclusion as the provincial Scientific Review panel, that there is no scientific basis for maintaining the moratorium. It also contained recommendations for public advisory bodies, baseline studies, and certain protected areas and exclusion zones.

In November 2004, the reports of the Public Review and Aboriginal Engagement processes were released. The Public Review report concluded that the many strongly held and vigorously polarized views did not provide a ready basis for any kind of public policy compromise at this time in regard to keeping or lifting the moratorium.

It presented four options for the federal government to consider: (1) keep the moratorium, (2) keep the moratorium or defer the decision on it while undertaking a suite of activities and making a decision in the future, (3) lift the moratorium and undertake a suite of activities prior to accepting any oil and gas activity applications, or (4) lift the moratorium.

The First Nations Engagement process concluded that the First Nations were either opposed to lifting the moratorium either altogether or at this time. The First Nations Engagement report recommended that the federal government collaborate with the First Nations at the outset to develop options; that the First Nations be provided with time, funding, and information on socioeconomic impacts; and that the federal and provincial governments partner with First Nations for next steps related to the potential lifting of the moratorium.

While it is still too early to tell, it is a positive sign that the scientific reviews commissioned by the provincial and federal governments each independently concluded there is no scientific basis to continue the wholesale ban on offshore oil and gas activity.

Even if the moratorium in British Columbia is lifted, however, a number of other issues would have to be addressed before any offshore development were to take place off the west coast, including: jurisdiction, land claims made by First Nations, tenure certainty, environmental issues, and regulatory issues.

Regulatory framework

Those who operate in the Canadian offshore area must navigate through the requirements of a number of federal and provincial legislation and regulations.

On the east coast, the federal, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador governments have entered into accords whereby the two levels of government have agreed to share the regulatory authority for the offshore area using a joint offshore management board. On the West Coast, no such accord has been agreed, and as such, there is some uncertainty not only with respect to the ownership of some of the basins but also the regulatory framework governing the offshore area of BC.

Regardless of whether an area is under an accord, the current regulatory framework governing the whole of Canada's offshore area is more robust than 30 years ago, when the moratorium was imposed on the west coast. In particular, a number of environmental statutes have been enacted by federal and provincial governments in the last 15 years that provide more checks and balances against offshore oil and gas operations that might imperil the environment.

One key statute is the 1995 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA). Pursuant to CEAA, an environmental assessment is required when there is a "project," a "federal authority," and a "trigger" event.

A "project" refers to an undertaking in relation to a physical work or an undertaking listed in the regulations. A "trigger" occurs when a "federal authority" (a federal agency, department or minister) proposes the project, provides financial assistance to the project, grants an interest in land in relation to the project, or exercises a regulatory duty specified in the regulations (such as the issuance of an authorization allowing for the harmful alteration, disruption, or destruction of fish habitat under the Fisheries Act, and/or the issuance of a disposal at sea permit under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999).

In the Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador offshore, almost any oil and gas exploration, development, or production activity will require the issuance of either the Fisheries Act authorization or the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 permit—both of which trigger the CEAA process.

Although the offshore areas of Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia are governed by joint federal-provincial offshore oil and gas boards, it is noteworthy that neither of the two triggers listed above is dependent on the existence of a joint board to engage the CEAA process. In fact, it appears that the broad scope of the CEAA triggers has generally ensured all offshore oil and gas activities in other parts of Canada that could have a significant impact on the marine environment will undergo a CEAA environmental assessment.

On the west coast, environmental assessments can also be conducted using the British Columbia Environmental Assessment Act, which applies to both "transmission pipelines" and "offshore oil and gas facilities." Further, the BC Minister of Sustainable Resource Management can designate a project as being reviewable where it may have a significant adverse environmental, economic, social, heritage, or health effect and is in the public interest.

Consultation with the public and members of affected First Nations on the potential effects of the project is a key component of the environmental assessment process and is tailored to each project. Minimum standards of notification, access to information and consultation must be met in each environmental assessment. In consulting with First Nations, the BC government must also meet its constitutional obligations with respect to aboriginal rights and title issues.

Given the potential for overlap in the environmental assessment processes, the federal and BC governments entered into a Canada-BC Environmental Assessment Agreement in 1997 to attempt to coordinate the two processes. This agreement was renewed earlier in 2004.

In addition to the project-specific environmental assessments, the federal cabinet directed federal departments in 1990 to consider environmental concerns at the strategic level of policies, plans, and programs development. A Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is to be conducted when a proposal is submitted to an individual minister or the cabinet for approval, and when the implementation of the proposal may result in important environmental effects. The federal public review process described above is an example of an SEA.

Other regulations

Other federal environmental statutes governing the offshore oil and gas industry include:

- Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act. Protects and conserves a variety of aquatic environments, and ensures resources are managed and used in a sustainable manner.

- Canada Oil & Gas Operations Act. Applies to nonaccord areas to promote safety, protection of the environment, and conservation of resources.

- Canada Wildlife Act. Establishes protected marine areas.

- Fisheries Act. Conserves and protects fish habitats by issuance of authorizations, and conserves and sustains the fisheries resource. The Marine Mammal Regulations, made under the act, protect marine mammals from disturbances (including seismic activity).

- Navigable Waters Protection Act. Protects navigable waters by issuance of approvals.

- Oceans Act. Requires the development and implementation of a national strategy and integrated management plans for the management of Canadian waters as well the development and implementation of a system of marine protected areas.

- Migratory Birds Convention Act. Protects migratory birds and migratory bird sanctuaries.

- Species at Risk Act. Protects listed species at risk and their habitat on federal lands and the aquatic environment. This covers all wildlife species listed as endangered, threatened, extirpated, or of special concern, as well as their critical habitat. Once a species has been listed under the act, recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, or stewardship plans must be developed. Emergency orders can effectively halt any type of oil and gas activity, regardless of the permits obtained by the proponent.

Overview

Given the growth and importance in environmental regulation over the last 15 years, navigating through the maze of statutes and regulations governing the offshore oil and gas industry is not easy; however, it is the robust nature of this regulatory framework that leads many to conclude that while the framework cannot provide absolute safeguards, it will ensure that offshore oil and gas development will not unreasonably imperil the Canadian marine environment.

It is impossible to know what the future holds for Canada's offshore oil and gas industry. However, while the opportunities for development of the industry are greatly different on each coast, there are nonetheless opportunities on the horizon.

Next: Basins off Newfoundland and Labrador offer oil and gas opportunities.

The authors

Paul Cassidy (paul.cassidy@ blakes.com) is a partner and head of the environmental law group at the Vancouver, BC, office of Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP. He provides advice on onshore and offshore environmental regulatory issues.

Gloria Chao (gloria.chao@ blakes.com) is an associate working in the environmental law group at the firm's Vancouver office. She provides advice on onshore and offshore environmental regulatory issues and has worked with key regulators in Atlantic Canada in the offshore oil and gas industry.