Deepwater Africa reaches turning point

Production from West Africa is at a turning point. The traditional West Africa shallow-water play is declining, and several deepwater developments discovered in the mid to late 1990s are now coming on stream.

The move to deeper waters off West Africa has been under way for many years, with extensive exploration activity in Nigeria and Angola as well as Equatorial Guinea and more recently Mauritania. As defined by Wood Mackenzie Ltd., "deep water" means 400 m or greater.

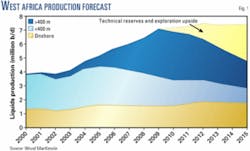

The relative immaturity of the deepwater sector and the scale of the opportunity still to be realized are shown in Fig. 1. In 2000, production from 400 m or more of water accounted for just 1% of total production across West Africa. This year we forecast this will rise to 14%, while by 2010 deepwater production will account for an estimated 50% of total West African production.

While growth in deep water is almost certain, that for water more than 1,500 m deep remains less so. The ultradeep water is still a technically and commercially challenging frontier that remains very much in an embryonic state.

Angola, Nigeria dominate

The successful development of deepwater reserves has become the most important source of new oil production across West Africa.

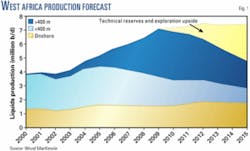

Fig. 2 illustrates the dominance of Angola and Nigeria in the deepwater production forecast across the whole West African region.

Angola's production has risen significantly in the last few years with five deepwater fields now on stream. In 2005, production from Angola's deep water is forecast to exceed 600,000 b/d, which will equate to over 80% of West Africa's deepwater production.

Surprisingly, Nigeria, despite a series of discoveries in the 1990s, still has only one deepwater development, ENI SPA's Abo field, on stream. Compared with Angola, deepwater production from Nigeria has been far slower to get going. It will not be until 2006 that production from Nigeria properly kicks in, with an estimated 280,000 b/d forecast to come from the deepwater Niger Delta. We estimate that deepwater production in Nigeria will jump from just 15,000 b/d in 2003 to 1.27 million b/d by 2010.

Fig. 3 shows the timeline of the major deepwater developments from award of the license through to the field coming on stream.

Field development times in Nigeria have lagged behind Angola. This can be attributed in part to the slow approval of projects and also to persistent technical problems experienced by many of the contractor groups.

Royal Dutch/Shell Group's Bonga field, discovered in 1996, is one such example of the disappointing progress in Nigeria's deep water to date. Production start, originally scheduled for 2003, has been delayed to mid-2005 due to technical problems with the floating production, storage, and off- loading vessel.

Fig. 3 also highlights the large difference in the number of deepwater projects, both on stream and planned, between Angola and Nigeria. With five fields already on stream and a further five projects under development, Angola's deepwater progress to date far exceeds that of Nigeria.

Angola's future developments are scheduled to come on stream in phases. In Nigeria, however, we identify three probable developments with the potential to commence production in 2008. Total SA operates two of these projects, Akpo and Usan, and may choose to move forward in a phased manner.

For the international operators, setting priorities for production from the deep water is key. In most deepwater fields in Nigeria, Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. (NNPC) has no direct funding interest so most fields will not suffer the funding constraints seen in the joint-venture (JV) operations.

Furthermore, the government share in Nigeria is lower in the deep water than in the onshore and shallow-water JV fields. Most deepwater fields are very large, which, coupled with the lower government take, is therefore extremely attractive to foreign companies, despite the large initial investment required.

In addition, the offshore location of deepwater fields significantly limits the potential for production disruptions from sabotage, armed clashes, and seizures of oil infrastructure as a result of civil conflicts, which have plagued companies operating onshore.

Equatorial Guinea, despite an active deepwater drilling campaign since 2002, has had limited deepwater success when compared with neighboring Nigeria or Angola. Deepwater discoveries to date have been smaller in Equatorial Guinea than in the other two countries.

Initial production forecasts from deepwater Ceiba field on Block G off Equatorial Guinea had to be downgraded due to the low pressure and complex nature of the reservoir. Although a further seven discoveries were made on the block, five of which will be developed as the Northern Block G Area due on stream in 2007, they are all much smaller than may have been hoped for. Zafiro oil field, despite being the largest single development in West Africa, produces mostly from the shallow water.

Mauritania also is establishing itself as a new deepwater oil and gas province following the success of the Chinguetti and Tiof discoveries, which are estimated to hold about 120 million bbl and 350 million bbl, respectively. With five discoveries made to date and a successful drilling rate so far, Mauritania could provide significant exploration upside from a number of prospects.

The main players

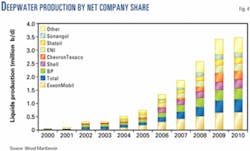

The past 8 years have seen the deepwater arena in both Angola and Nigeria evolve from a frontier area into a strategic and core region for a number of international companies seeking higher returns.

Most of the majors have significant interests in both countries' deepwater acreage. BP PLC and Shell are the two main exceptions. BP, despite once having the biggest deepwater exploration position in Nigeria (prior to its merger with Amoco Corp.), now has no interests in the deepwater Niger Delta. Conversely, Shell has recently indicated its intention to withdraw from Angola's deep water. This decision came in April 2004 when the company announced the sale of its 50% stake in BP-operated Block 18. Shell still has a 15% stake in ultradeepwater Block 34, which is operated by Sonangol; however, given the lack of exploration success we expect the block to be relinquished at the end of its term, in September of this year.

In Angola, key developments across the four deepwater blocks are dominated by four of the oil majors with Blocks 14, 15, 17, and 18—operated by ChevronTexaco Corp., ExxonMobil Corp., Total, and BP, respectively. ExxonMobil and BP also have equity interests in the Total-operated Block 17.

In Nigeria, ENI operates Abo field, which is the only on-stream project. The three deepwater projects currently under development (Bonga, Erha, and Agbami) are again dominated by the oil majors and operated by Shell, ExxonMobil, and ChevronTexaco, respectively. Total is looking at developing Usan and Akpo fields.

Fig. 4 shows companies' shares of past and expected production from deepwater Africa.

Major deepwater projects

The West Africa region holds some of the world's most significant projects.

Angola

In Angola, there are four key deepwater development areas, which account for nearly 80% of the remaining oil in Angola—Blocks 14, 15, 17, and 18 (Fig. 5).

Block 14 is the deepwater extension of the ChevronTexaco-operated Cabinda concession, which contains seven commercial discoveries. The first of these to be developed on the block was Kuito field.

ChevronTexaco undertook a fast-track, phased development approach for Kuito, with first production less than 3 years after field discovery. The field uses a large FPSO facility moored in about 400 m of water. Five phases of the Kuito development have now been executed, including the installation of facilities to process up to 100,000 b/d of oil and inject 135,000 b/d of water. In addition, 29 wells have been drilled. Total capital costs for Kuito field are estimated to be $1.4 billion.

Benguela, Belize, Lobito, and Tomboco (BBLT) is the second major development on Block 14. The BBLT development is located 80 km offshore in around 400 m of water and will be exploited as a single, large, stand-alone development. A single project has been chosen as the fields, while fault-separated, contain the same reservoirs. The partners have chosen a compliant piled tower (CPT), the first of its kind outside of the Gulf of Mexico, as the development solution for the project. The CPT, which will measure just under 400 m in height, is expected to have a capacity of around 210,000 b/d.

The joint development will target just under 500 million bbl, although there is potential for a further 150 million bbl to be exploited at a later date. Total capital costs for the BBLT development is expected to be $2.4 billion.

On ExxonMobil-operated Block 15, there are eight commercial discoveries being developed or planned for development.

Kizomba A is the largest on-stream development on Block 15 to date. The project is exploiting two discoveries. Development of Hungo and Chocalho fields involves an "extended" tension leg platform (ETLP) as a dry completion unit with production delivered to a new-build 2.2 million-bbl-capacity FPSO. After separation, water and gas are reinjected from the FPSO via five risers to subsea wellheads. The Kizomba A development is the first dry completion unit to be installed in deepwater West Africa. Despite the initially higher development costs associated with the ETLP, part of the rationale for using the dry tree concept is that overall drilling costs should be reduced over field life. The project is expected to reach peak production of 250,000 b/d this year, exploiting around 1 billion bbl of recoverable reserves. Capital expenditure for Kizomba A is estimated at around $3.5 billion.

The Block 15 consortium is also planning to develop the remaining discoveries in the area as two separate projects, which will be known as the Kizomba B and Kizomba C developments.

Block 17 contains 10 commercial discoveries, all expected to be developed. Girassol, the first commercial discovery on Block 17, produces from subsea wells tied back to an FPSO via three riser towers. Jasmim field, or the Girassol C complex, also produces through the Girassol facilities. Once spare capacity becomes available on the Girassol FPSO, it is understood that Rosa, Cravo, and Lirio fields will produce through the Girassol FPSO facilities.

Dalia was the second commercial discovery on Block 17. Camelia field, discovered in 1999, is now considered part of the Dalia structure. Development is under way and will involve subsea wells tied back to a single, large FPSO. The project is on track, with no delays anticipated prior to start-up in October 2006. This project will be more expensive than Girassol due to an increase in FPSO costs caused in part by the hike in worldwide steel prices.

The Dalia design is expected to mirror that of the neighboring Girassol development. One exception will be that the Dalia FPSO will require additional processing capacity because the crude is heavier so the FPSO will have two processing trains. Capital expenditure for the development is estimated at $4 billion, compared with $3 billion for Girassol.

Rosa is the second major field under development on Block 17. Total is planning to develop the Rosa complex using subsea wells tied back to the Girassol FPSO vessel, replacing Girassol production as it starts to decline. The subsea tie-back involved will be technically challenging due to the long distance to the Girassol FPSO. In addition, Total plans to upgrade the Girassol FPSO as part of the Rosa development, adding to the project's capital expenditure, which we estimate at $1.7 billion.

BP-operated Block 18 contains the development area known as Greater Plutonio. Plans for the joint development involve the use of subsea wells tied back to a single FPSO facility that has a storage capacity of 2 million bbl. With a 31/2-year development timeline, first production is forecast for fourth quarter 2007. Capital expenditure for the Greater Plutonio development has been estimated at $4 billion over the life of the fields. This would equate to as much as $6.50/bbl, evidence that Block 18 is expected to be costly to exploit due to the scattered distribution of its reserves. It is also expected that the technical challenges to be overcome will prove costly.

Two further discoveries, Cesio-1 and Chumbo-1, were made on the block during 2003. If developed, Cesio could potentially be tied back to the Greater Plutonio FPSO. Chumbo would be developed separately.

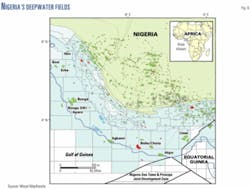

Nigeria

The deepwater Niger Delta is expected to be a major contributor to Nigeria's crude production from 2006. Nigeria's first deepwater field, Abo, came on stream in 2003. Abo is relatively small but will be followed by the giant Bonga and Erha developments in 2005 and 2006, respectively (Fig. 6).

- ENI-operated Abo field is the only deepwater development on stream in Nigeria to date. Production reached a plateau of around 30,000 b/d by mid-2004. Total capital expenditure is estimated at $275 million.

- Bonga field lies on deepwater Block OML 118, which is in the western part of the Niger Delta, about 75 km offshore. Bonga is the first major deepwater development in Nigeria. First production was originally planned for 2003 and subsequently revised to early 2004. However, technical issues have delayed start-up until 2005. Production will come from subsea wells tied back to the Bonga FPSO. Bonga SW will form a new stand-alone development on the block.

Peak oil production and sales gas rates from Bonga will be 250,000 b/d and around 150 MMcfd. Bonga SW/Aparo could be on stream by 2008. Total production, net to OML 118, we forecast to peak for oil at 350,000 b/d in 2010 and for gas at around 250 MMcfd in 2010.

The capital expenditure for the Bonga development is estimated at more than $3 billion.

Likely capital expenditure for the Bonga SW discovery is uncertain at this early stage but is expected to be more than that of the initial Bonga development.

- The deepwater Block OPL 209 contains Erha and Bosi fields, which are in the western part of the Niger Delta about 100 km from the Nigerian coast. The fields will be developed with subsea wells tied back to an FPSO.

Production from Bosi and Erha fields is scheduled to commence in 2006. Recoverable reserves of 650 million bbl of oil will be produced over 20 years with a peak production rate of 200,000 b/d. The total capital costs in 2004 terms are estimated at $2.8 billion.

- After a faltering progress since its discovery in 1998, the ChevronTexaco-operated Agbami field is now under development. ChevronTexaco expects first production in late 2007 and a plateau of 250,000 b/d from 2008. Capital costs were initially expected to be around $3 billion but now appear to be approaching $4.5 billion. The 800-million-bbl field had been dogged by delays brought about by a number of factors. A reorganization of the newly merged ChevronTexaco soon after Agbami's discovery led to a change in the development concept and reissuing of tenders. The field is unitized over two blocks, which increased the number of partners and time taken to allocate reserves between blocks. Although these hurdles have been overcome, a project partner, the indigenous company Famfa Oil Ltd. of Nigeria, is locked in a legal dispute with NNPC over equity participation that has slowed development of the field.

- Total-operated Usan field, the easternmost of Nigeria's giant deepwater fields, lies in water 700-800 m deep. Discovered in 2001, Usan drilling has included five successful appraisal wells, the three most recent of which added substantially to reserves, which are now estimated at 600 million bbl.

Total plans a fast-track development, which will probably involve subsea wells tied back to an FPSO. First production from Usan is expected in 2008, with a pla- teau of 185,000 b/d. There is a good chance that this development plan can be achieved. As the field is relatively shallow, royalty will be payable to the government upon first production. This is unlike other big deepwater fields in Nigeria, which are deeper than 1,000 m and thus free from royalty obligation. It is, therefore, in NNPC's interest to approve development of Usan ahead of some of the other discovered fields. For fields in greater than 1,000 m of water NNPC will see only a share of revenue once the huge capital costs are recovered. Also in Usan's favor are the lack of unitization issues and absence of indigenous participation, two factors that have delayed other projects.

- Akpo is a 620 million bbl, 3.5 tcf gas and condensate field located at the southern limits of Nigeria's territorial waters. Reserves of light oil are also present in some reservoirs.

Total, which operates the field on behalf of local operator South Atlantic Petroleum Ltd. (Sapetro), plans to produce 140,000 b/d of condensate and 300 MMcfd of gas via subsea wells and an FPSO.

Gas production will be piped to the Nigerian LNG plant at Bonny, where it will feed Train 6. NNPC might attempt to back in to the majority of Sapetro's equity, which could result in legal action and delay development approval.

Deepwater future

With a number of deepwater discoveries across Angola and Nigeria now on stream and in various stages of development, we believe the key to the future success and growth of the deep water is continued exploration.

The deep water has experienced substantial growth in recent years, and with discoveries having been much larger than those found in shallower waters, we also expect there to be a migration into even deeper waters.

Although at present, ultradeep water represents only a fraction of deepwater expenditure, deepwater exploration should remain critical to any operator's upstream strategy within the region, where the major players have more to lose by being conservative than by taking considered risks. As deepwater production assumes an increasing level of normality, ultradeepwater prospects will pick up the mantle of frontier territory.

In Angola, development is expected in the next few years of recent discoveries on ultradeepwater Blocks 31 and 32. On Block 31, BP and partners had been expected to announce a development decision by the end of 2004. With four fields on Block 31 located within 30 km of each other, the project dynamics look similar to that of the Greater Plutonio development on Block 18; therefore, the use of one giant FPSO is likely.

On Block 32, Total is believed to be considering both a stand-alone cluster development as well as the option of tying the fields back to the Block 17 infrastructure.

In Nigeria, further development delays on deepwater projects are likely. The government is now indicating that it wants to review existing production-sharing contracts with deepwater operators. With the next licensing round planned for early this year, if true, this does not bode well.

The various difficulties seen in Nigeria, however, have not discouraged deepwater activity nor weakened the widely held view that the current finds represent only a fraction of the deepwater potential. In Nigeria's ultradeep acreage, the drilling results on a number of blocks are eagerly awaited. With disappointing results to date in the area, the results may indicate how prospective the ultradeep margins may be and influence the forthcoming bidding round.

In the future, the relative importance of the deep water off West Africa is expected to increase further as exploration success continues and advances in subsea technology overcome the deepwater challenges. Deepwater developments may be large in terms of size, cost, and risk, but they also carry large potential rewards for the oil companies involved.

The authors

James McLennan is senior consultant, African energy, with Wood Mackenzie Ltd., which he joined early in 2003. Before joining Wood Mackenzie, he worked for Deutsche Bank Corporate Finance in London. McLennan holds an MA in accountancy from the University of Aberdeen.

Stewart Williams is managing consultant, African energy, with Wood Mackenzie. He joined the firm in 1996 and before that was senior geophysicist with GETECH. Williams holds a BEng Honors degree in electrical and electronic engineering and an MSc in exploration geophysics from Leeds University.