Trinidad and Tobago banking its future on natural gas, but energy policy still evolving

Last in a series.

Trinidad and Tobago has banked its future on natural gas.

The Caribbean republic has set a target for economic growth that calls for it to achieve the status of a developed nation by 2020. And the fulcrum for leveraging that growth is natural gas-based industrial development and exports.

By then, Trinidad and Tobago expects its hydrocarbon production to meet or exceed 1 million boe/d, according to the new minister of energy and energy industries, Eric A. Williams. That breaks out as 5 bscfd of gas and 160,000 b/d of crude oil and condensate. Production in 2001 reached 124,000 b/d of crude and condensate and 1.4 bscfd of gas.

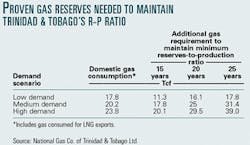

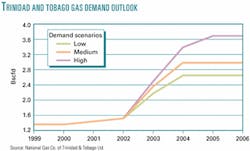

Gas production is expected to climb to almost 3.7 bscfd by 2006, and proven reserves are likely to top 20 tcf this year. Analysis by the state-owned gas company, National Gas Co. of Trinidad & Tobago Ltd. (NGC), stresses a need to prove an additional 39 tcf to support an acceptable reserves-to-production (R-P) ratio to sustain demand scenarios to 2020.

Getting to that point will require a careful calibration of just the right balance of monetization of its burgeoning gas reserves for export vs. expanding an industrial base supported by those reserves.

And key to executing the right balance will be growing investments by foreign oil and gas companies, the energy minister contends.

Williams, who took office in December 2001 with the new government following nationwide elections last fall, covered these points in a luncheon speech sponsored by London-based Gaffney Cline & Associates Inc. and the Institute for the Study of Earth and Man at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, in Houston Mar. 22.

He is a geophysicist by training and has worked both for state-owned oil company Petroleum Co. of Trinidad & Tobago Ltd. and US-based seismic contractors. Williams became a member of Trinidad and Tobago's Parliament in 1995, and is currently CEO of local seismic contractor Maranatha Geophysical Services.

Petroleum status

The boom in natural gas exploration and development off Trinidad has helped the twin-island nation transform itself from a sleepy backwater oil producer into a major player on the Western Hemisphere gas scene.

Williams cited a turning point in energy policy in the early 1970s when the nation's prime minister, Eric Williams (no relation), convened a multisectoral conference on the optimization of petroleum resources.

"The government made the tacit admission then that it regarded crude oil as the dominant resource in Trinidad and Tobago," Energy Minister Williams said.

The blueprint that emerged focused on how to use the country's surplus revenues from the export of oil and refined products to develop a world-class port facility and industrial estate at Point Lisas, Trinidad, with state-sponsored, gas-based investments in ammonia, methanol, iron and steel production, and power generation. The main emphasis was on jobs creation.

"This historic conference endorsed the use of gas as a means of industrialization, rather than monetization, as was the case with oil," Williams said. "At that time, LNG was given low priority, and projects that gave greater value added and potential for downstream development were considered more important."

Central to this vision was the creation of NGC in 1975, intended to oversee the purchase and sale of natural gas to commercial and industrial users.

Gas takes the lead

The government's focus changed as the country's natural gas endowment grew and its oil sector declined.

In 1981, a government white paper outlined steps needed to diversify the Trinidad and Tobago economic output based on natural gas.

"Policies that favored natural gas as a premium energy resource and as a potential generator of foreign exchange were supported," Williams said. "This signaled a change in philosophy, an intention to monetize our natural gas in order to help offset the fall in gross national revenue as the oil sector began to show signs of decline."

The result was a surge in gas production growth of 10%/year, with sales rocketing to more than 1.4 bscfd by 2001 from 250 MMscfd in 1981.

Williams attributes the explosive output growth to state incentives, NGC's success in attracting gas-based industries, and continuing exploration successes by offshore producers: "In essence, this [growth] was based on a demand-led growth model."

The tiny nation also has emerged as the world's No. 1 exporter of both ammonia and methanol and will become, Williams predicts, the world's fifth largest exporter of LNG by 2005. Expansions under way at the Atlantic LNG Co. of Trinidad & Tobago Ltd. LNG (ALNG) export plant at Port Fortin, Trinidad, could go beyond the second and third trains currently under construction to as many as six trains.

"In the case of all three of these commodities, there exist firm policy proposals, and discussions are under way for the construction of new plants to rapidly expand existing capacity," he added.

Beyond those three, the government has targeted as priorities projects to produce ethylene, acetic acid, dimethyl ether, and products derived from gas-to-liquids processes.

Williams also cited his government's continuing efforts to attract foreign direct investment to the nation's petroleum and energy sectors, particularly export-oriented industrial projects. Paramount among these efforts are maintaining an investor-friendly regulatory and fiscal regime, strong leasing programs, and a competitive gas price structure.

New energy policy

Trinidad and Tobago is implementing new energy policy initiatives designed to further enhance the attractiveness to investors of a sector that accounts for over 70% of the country's foreign exchange earnings and 25% of its gross domestic product.

There are three main drivers for Trinidad and Tobago's new energy policy:

- Good governance. The government recently established a standing committee on energy (SCE) to represent all stakeholders' interests, as well as the required expertise, that is designed to ensure all energy-related decisions are handled efficiently and transparently.

- Natural gas master plan (NGMP) recommendations. Following an August 2001 audit by Houston-based Ryder Scott Co. of Trinidad and Tobago's proven natural gas reserves-pegged at 19.7 tcf as of January 2001-and the development of the NGMP by Gaffney Cline, the government is pursuing further efforts to diversify its gas-based economic portfolio (for NGMP details, see OGJ, Mar. 11, 2002, p. 22).

- Sustainable gas development. This initiative focuses on Trinidad and Tobago's efforts to use energy sector growth as a vehicle for investing in and developing its local capabilities and for building wealth at the grassroots level.

Local capabilities

For that last point, Williams stresses a need to develop not only local skills and businesses that support the energy value chain but also those applicable to the nonenergy sectors.

While that initiative includes guidelines for ensuring local content in projects, Williams insists that the requirement is not "being superficially about ensuring the attainment of minimum local content quotas in energy operations.

"Far from it, we are encouraging a collaborative approach between our partners to assist locals to take on more value-added roles, management, and ownership in our economy."

He cited BP PLC's Trinidadian subsidiary's creation of a "sustainable developments" department as an example of that approach. Other proposals he cited include:

- Building an in-country engineering design capability.

- Expanding the local role in the management and ownership of ALNG shipping and transportation.

- Greater local participation in the production of ethylene.

- Alliances between global and local energy service providers.

Williams listed specifically a need for his country to develop its own engineering capabilities in these areas of the oil and gas sector: subsurface services, including seismic and logging; well drilling and rig operations; engineering and construction services; fabrication capabilities; operations support and logistics; and consulting services.

Policy issues

SCE has identified from the NGMP a number of policy issues that warrant further consideration and analysis, Williams said.

They include:

- A review of fiscal incentives and tax policies-particularly with regard to ammonia and methanol.

- A review of the oil and gas tax regime.

- A reprioritization of goals in the gas sector.

- Prioritization of which downstream gas-based products to pursue aggressively.

- LNG exports expansion.

- Development of new sites for industrial estates, particularly the northeastern corner of Trinidad, near Galeota Beach.

- Consideration of direct sale of natural gas by producers to consumers, which raises the prospect of privatizing NGC.

- Negotiations with major producers over royalty issues.

Regarding the last point, Williams noted talks under way with BP, the country's biggest gas producer, to renegotiate its gas royalties, which he put at 1.5¢ (TT)/Mcf.

"The playing field needs to be a little more level," he said. "The opening negotiations with BP are not likely to be adversarial, but clearly there are issues that need to be discussed."

Williams describes his country's new energy policy as a "work in progress" that will see more new issues emerge. He cited a major new offshore oil discovery by a group led by Australia's BHP Billiton Ltd.-which was instead targeting natural gas-and a major new onshore gas discovery by Vintage Oil Co.-which instead was targeting oil-as examples of energy sector developments that pose new opportunties and challenges for an evolving energy policy.

Maintaining R-P ratio

Among those energy sector challenges are finding and developing enough gas to support ambitious downstream industries, according to NGC.

Trinidad and Tobago faces the challenge of sustaining a minimally acceptable R-P ratio to ensure a healthy supply-demand balance in the next 2 decades.

Two NGC officials, writing in the company's in-house magazine Gasco News last year, developed a mathematical model to determine an optimal reserve addition profile that meets all projected demand scenarios.

That model showed that the country must boost reserves by as much as 39 tcf over the next 20 years in order to satisfy a high-demand scenario while also sustaining minimum R-P of 25 years, according to Godfrey Ransome and Haydn I. Furlonge, analysts with NGC's business development group.

"This substantial volume would undoubtedly pose a significant exploration challenge to Trinidad and Tobago," they wrote. "However, substantial exploration activity is taking place, and the prospects are promising."

For security of supply purposes to sustain a 25-year R-P ratio under medium and low-demand scenarios, Ransome and Furlonge estimated required reserves additions of 31.4 tcf and 17.8 tcf, respectively (see table).

In the short term, at least 12.2 tcf of reserves would have to be added over the next 6 years in order to satisfy local gas consumption projections under the high-demand scenario (see chart).

The two analysts contend that substantial new reserves, notably in unexplored areas, will be required to meet the long-term high-demand scenario. This effort could cost $3 billion in capital spending for exploration and development, they estimated.

The analysts also studied the prospect of bolstering the country's gas supply-demand outlook by considering the option of importing natural gas from Venezuela.

A group of companies led by ExxonMobil Corp. and Venezuela's state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela SA in the early 1990s proposed an LNG export plant on Venezuela's Paria Peninsula based on gas discoveries in the Gulf of Paria that separates Venezuela and Trinidad. That project was shelved as uneconomic, while Trinidad and Tobago placed its own LNG export project on stream in record time for such a project; a downsized version is still alive.

"It may also be worthwhile forming alliances with Venezuela to source their stranded reserves, considering the close proximity of their reservoirs and their new favorable gas laws," they wrote.

Ransome and Furlonge also recommended that Trinidad and Tobago's gas pipeline capacity of 1.4 bcfd (excluding gas for LNG production) needs to be expanded over the long term to match growing capacity for the medium and high-demand growth scenarios. Those scenarios envision added capacity increments of 160 MMscfd and 840 MMscfd, respectively.

Gas export concerns

Furlonge, writing in a separate article in Gasco News, expressed concerns over the nation's R-P ratio-and its ability to support a broader-based downstream gas industry-becoming compromised by a rapid ramp-up in exports of the country's gas.

In an analysis of R-P ratios for LNG exporting countries that ranged from 7 to 351 years, he noted that Trinidad and Tobago's R-P ratio fell near the lower end of the range and was likely to fall still further when two more LNG trains come on stream.

"Is this a precarious position, or does it mean that resources are being fully utilized?" he wrote. "It's interesting to note that the top three LNG producing countries [Indonesia, Algeria, and Malaysia] have R-P ratios in the same range as Trinidad and Tobago's current value.

"However, the difference is that these countries have significantly more reservesellipseThus, one or two more LNG plants will not result in a significant drop in their R-P ratiosellipseand therefore the ability of their downstream industries to expand further will not be affected."

Furlonge also considered the percentage of gas production that is exported among LNG exporters, reckoning that Trinidad and Tobago will be exporting about 55% of its gas output by next year.

"Given that this is a large percentage, and that Trinidad and Tobago does not currently have reserves as large as those of other major [LNG] exporting countries, it is even more critical that an assessment be performed to determine whether further LNG trains-which could result in 70% of gas production being exported [with Train IV]-is in fact congruent with the best utilization of reserves."

Eric A. Williams

Trinidad's continuing efforts to attract foreign direct investment to the nation's petroleum and energy sectors, particularly export-oriented industrial projects, center on maintaining an investor-friendly regulatory and fiscal regime, strong leasing programs, and a competitive gas price structure.

Guidelines for ensuring local content in projects are not superficially about ensuring the attainment of minimum local content quotas in energy operations. Far from it, we are encouraging a collaborative approach between our partners to assist locals to take on more value-added roles, management, and ownership in our economy.