Canadian bitumen stands poised to expand to US markets

Increased pipeline movement of raw bitumen production from Canada to the US could mitigate North America's vulnerability to crude supply disruptions and require expansion of existing pipelines or construction of new pipelines.

As discussed previously (OGJ, Oct 28, 2002, p. 64.) and in a recent report issued by Canada's National Energy Board,1 Western Canada has substantial heavy crude oil and bitumen resources. The earlier article also commented on diluent availability and implications of constraints in diluent supply and pricing on pipeline transportation costs.

Recent months have seen various announcements relating to existing plans or new proposals for bitumen production in Alberta and proposals for new pipelines or conversion of existing pipelines. The target markets have included a pipeline to the West Coast of Canada with marine movements to California and Asia. There have also been proposals for new pipeline connections to Kansas and Oklahoma and the US Gulf Coast.

This article focuses on the market opportunity for Canadian bitumen in Kansas, Oklahoma, and on the US Gulf Coast. It also addresses important questions about how and where the Alberta bitumen should be upgraded and how and to where it should be transported. These are inter-related questions.

Market expansion

Late in 2003, Enbridge Pipelines announced plans for a new pipeline, the Southern Access, from Superior, Wis., to Wood River, Ill., which would connect with an existing pipeline from Cushing, Okla. (Spearhead).2 The proposed Southern Access pipeline could also connect with another existing pipeline, which connects the US Gulf Coast to Patoka, Ill. Both pipelines would be reversed.

The 2003 NEB annual report3 says that there have been marine exports from Terasen Inc.'s Westridge terminal in Vancouver to California and Asia. In private discussions, the NEB staff has confirmed that these existing exports have included both heavy synthetic crude oil and bitumen.

Several recent announcements about pipelines and the expansion of Canadian bitumen supply indicate that Alberta bitumen producers now recognize the need to expand access for Canadian synthetic crude oil and bitumen into new markets.4 5 In a sense, this evolution is logical and consistent with the historical pattern of the market expansions for Canadian exports of oil and natural gas.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Canadian efforts relating to heavy crude marketing focused on the US Northern Tier. During the 1990s, EnCana Inc. took the initiative in the development of the Express crude oil pipeline, which was designed to serve inland markets in US Petroleum Administration for Defense District IV (PADD IV) and PADD II. (See accompanying US PADD map.) Express also acquired the existing Platte pipeline system which provided a connection to Wood River, Ill.

The proposed Southern Access pipeline from Superior would expand the capability to move Canadian bitumen to Wood River and thus compete with the existing Platte pipeline.

The expanded pipeline capacity to Wood River may be important for the sponsors of the Surmont project, which contemplates delivery of bitumen to ConocoPhillips's refinery at Wood River. Based on data published by the US Energy Information Administration, this Wood River refinery has a 55,000-b/d asphalt plant.

The proposed Spearhead Pipeline is an existing 22 and 24-in. pipeline to Cushing. The largest refinery in Oklahoma is the ConocoPhillips refinery at Ponca City that has a delayed coker for which the reported capacity is 26,900 b/d, based on EIA data. The proposed Southern Access system could also connect with existing pipelines to the US Gulf Coast and should be able to handle "synbit" (bitumen diluted with synthetic crude oil) or upgraded crude from one large project such as Imperial Oil Ltd. and ExxonMobil Corp.'s Kearl Lake in the Athabasca region. For example ExxonMobil has a large refinery at Beaumont, Tex., that has a delayed coker for which the reported capacity is 50,700 b/d.

While the proposed pipelines will target inland refineries at Wood River and in Oklahoma, these announcements also give credibility to the concept of moving Canadian bitumen to the US Gulf Coast.

Producers that elect to support the movement of Canadian bitumen to the gulf will apparently accept that they would be competing with PDVSA and Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex). For large integrated companies, this may not be a difficult position, but this position is likely more challenging for companies with investments in Venezuela and for independent Canadian bitumen producers.

Market analysis

In very simple terms, the target markets for Canadian heavy crude oil and bitumen are refineries with asphalt plants and cokers. This section will survey the capacities of refineries in the prospective target markets in the US Midcontinent and Gulf Coast vs. refinery capacities in the currently connected markets in upper Midwest of PADD II and the states of Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado in PADD IV.

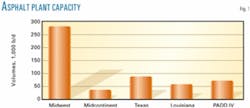

Fig. 1 shows the asphalt plant capacities in the existing and target markets. In Texas and Louisiana, asphalt plant capacities are 89,000 b/d and 62,000 b/d, respectively. In the Midcontinent, all of the 34,000-b/d asphalt capacity is in Oklahoma.

In the currently connected markets, most of the 69,000-b/d asphalt capacity in PADD IV is in Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado. The Midwest refineries have asphalt capacity of 283,000 b/d, and most of this capacity is in Minnesota, Illinois, and Indiana, which are the heavily populated and industrialized areas.

Because of their asphalt markets, both the Midwest and PADD IV were logical destinations for Canadian heavy crude oil and bitumen. Unfortunately, the asphalt markets in the upper Midwest and in PADD IV are seasonal, which generally causes swings in the demand for heavy crude and bitumen.

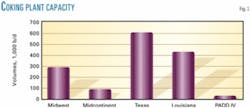

Fig. 2 shows that there is substantial coking capacity in the US Midwest. This capacity is currently 296,000 b/d, with 126,000 b/d in Illinois and lesser amounts in Minnesota, Ohio, and Indiana.

The coking capacities in the Midcontinent and PADD IV are only 94,000 b/d and 47,000 b/d, respectively. In contrast, the coking capacities in Texas and Louisiana are 610,000 b/d and 454,000 b/d, respectively, and together exceed the Midwest coking capacity by a factor of more than 3, the Midcontinent by 10, and PADD IV by more than 20.

Another measure of the ability of refineries to handle heavy, sour crude oil or bitumen is the refinery sulfur-plant capacity. At refineries in the Midwest, the sulfur-plant capacity exceeds 4,000 short tons/day (ST/day), but sulfur-plant capacities in Texas and Louisiana exceed 10,000 ST/day and 5,000 ST/day, respectively.

In contrast, refinery sulfur-plant capacity in PADD IV refineries is 674 ST/day but only 172 ST/day in the Midcontinent refineries. Fig. 3 illustrates these capacities, based on EIA data. The small refinery sulfur-plant capacities in Midcontinent refineries imply that these refineries are not designed to utilize sour crude oils.

Bitumen supply development

There are currently three large oil sands mining operations in the Athabasca area of Alberta. These mines have extraction processes to liberate the bitumen from the sand.

Both Suncor Energy Inc. and Syncrude Canada Ltd. constructed their two initial upgrading facilities near Fort McMurray in northern Alberta at sites adjacent their extraction plants. A consortium of Shell Canada Ltd. (60%), Chevron Canada Ltd. (20%), and Western Oil Sands Trust (20%) has constructed a new upgrading facility at Scotford, north of Edmonton and adjacent Shell Canada's refinery and petrochemical complex at Scotford.

Construction of the new facility by this joint venture and expansion of the Suncor plant have both experienced significant cost overruns. Unlike the Suncor and Syncrude plants, the joint venture plant at Scotford does not have a coker.

In addition to the existing mining operations, there are proposals for new mining projects, and two such projects have obtained provincial approvals for mining projects. One of the approved projects includes an upgrading facility.

There have also been announcements for other prospective oil sands mining projects including the Imperial Oil Ltd. and ExxonMobil announcement6 of their Kearl Lake Oil Sands Project.

These proposed mining projects are in the Athabasca region and could include upgrading projects in the Athabasca or Edmonton areas. Imperial Oil has stated that an upgrading investment at its Edmonton refinery could increase the expected capital cost of the Kearl Lake project from $5 billion (Can.) to $8 billion. By difference, this implies that the cost of an upgrader at the existing Edmonton refinery would be $3 billion (Can.).

Steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and various other production methods can recover bitumen from reservoirs that are not suitable for surface mining. Fig. 4 shows that Alberta bitumen production exceeded 350,000 b/d by yearend 2003 compared with 300,000 b/d in 2002 and 150,000 b/d at the beginning of 1996. These data exclude bitumen processed at oil sands upgraders. A significant portion of this raw bitumen production is in the Cold Lake area, but the bitumen production in the Athabasca region is increasing.

In March 2004, the Canadian Oil Sands Trust (COST) said that there had been a major cost overrun at the Syncrude expansion, currently under way.7 The most recent estimate is $7.8 billion (Can.), which is 36% higher than the September 2002 estimate of $5.7 billion and almost double the initial estimate of about $4 billion (Can.).

Although this is bad news, there was also some good news. Specifically, the $700 million (Can.) bitumen production expansion component of Stage 3 for Syncrude, known as the Aurora 2 mine, already has been completed on time and only 4% over budget.7

Bitumen upgrading in Canada

There is significant heavy oil and bitumen resource potential in Western Canada with several projects in various stages of development. There are also some expectations that cost-effective approaches or processes for upgrading will be developed.

Conventional logic suggests that upgrading at existing refineries or oil sands upgraders should have lower capital costs than new grassroots facilities. Given the history of recent projects, any new upgraders constructed in Western Canada will be vulnerable to cost overruns.

The oil sands upgraders in Western Canada also face the need to handle the sulfur. Operators of one of the oil sands upgraders have decided to rail their sulfur to the US Gulf Coast. The cost of moving sulfur by rail is significant and must be factored into overall project economics for upgraders that yield a high quality, low-sulfur synthetic crude oil. Nevertheless, there are some independent proposals that contemplate upgrading projects in Alberta.8

Nexen Inc. has also announced the $3 billion (Can.) Long Lake project, which is integrated with a field upgrader. Earlier announcements indicated that the Nexen field upgrader would turn the bitumen into a 22° API synthetic crude oil.

While recent attention on Alberta oil sands development has focused on the cost overruns at the upgrader stage,7 the real constraint on Canadian oil sands and bitumen development is market access.

All oil sands mine development efforts to date have included upgrading near the mine or at refineries in Alberta. Experience with the construction of upgrading projects in Alberta and Saskatchewan shows that these projects are vulnerable to cost overruns. There were also two upgraders built at Lloydminster and Regina to process bitumen from in situ production; however, these facilities may not have achieved economies of scale.

Expansion of either of these facilities may also be vulnerable to cost overruns.

Bitumen upgrading in the US

Coking projects at existing refineries on the US Gulf Coast have reported capital costs of less than $1 billion (US) for cokers with capacities in the 80,000-b/d range. These US upgrading projects may also be justified in part by expansion of their markets for lighter products including gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. In addition, more-stringent product specifications may require hydrotreating to reduce sulfur levels in these products.

EIA data indicate the coking capacity in Texas and Louisiana refineries exceeds 1 million b/d. Several new cokers have been built on the US Gulf Coast during the last 5 to 10 years, and many US Gulf Coast refiners are prepared to invest in their facilities to maintain their viability.

Many of the refineries in other regions of the US have not attracted sustaining capital and are vulnerable to refined product imports. For example, development of the Centennial pipeline has greatly increased the capacity to move refined products into the Chicago and nearby areas.

This reduces the attractiveness of the Midwest as a destination for expanded Canadian deliveries of bitumen and synthetic crude oil. While there may be some market potential for synthetic crude at inland refineries such as those in Oklahoma, the relatively low sulfur-plant capacities at Oklahoma refineries implies that they may not be able to handle significant volumes of heavy, sour bitumen.

There is a large potential market for Canadian heavy crude oil and bitumen in US Gulf Coast refineries. For many years, Alberta has encouraged US investment in the Alberta oil and gas industry.

The Canadian affiliates of several US and international oil companies already have interests in Canadian oil sands and bitumen resources.

From a US perspective, development of the Canadian bitumen resources will require both pipeline investments in the US and upgrading investments in the US.

From a Canadian perspective, there will be investments in production and pipelines, and possibly some upgrading at existing refineries or new oil sands upgraders. This situation should allow industry participants to optimize the development based on economic criteria, and environmental and security considerations.

Expansion of US upgrading capabilities would mitigate the risk of further cost overruns at new upgraders in Western Canada.

For oil sands, initial development required construction of massive upgraders. Suncor, Syncrude, and the more recent joint venture facility at Scotford have been developed on this basis.

It is also prudent and appropriate for the refiners in Western Canada to investigate modifications to their refineries, which would allow them to process bitumen or heavier crudes.

Since there are independent producers in Canada and independent refiners in the US, these parties should look for ways to connect. As discussed, the cost of upgrading in the US at existing refineries should be less than at new grassroots facilities in Canada.

Existing and prospective Canadian bitumen producers face options to access new markets.

Marine exports and the focus on expanded market access provide clear indications that the currently connected markets for Canadian heavy crude oil, bitumen, and synthetic crude oil in the US Midwest and PADD IV may be approaching saturation.

Transportation

The challenge for Canadian producers and US refiners is development of efficient and cost-effective transportation systems to serve new markets.

The commercial arrangements should provide an economic incentive for Canadian producers to make the investment in production and for US refiners to purchase the crude oil and bitumen and to make the investment in refining facilities and upgrading that ensure their long-term viability.

Bitumen can be transported in existing pipelines if it has been upgraded in Alberta, or if a diluent such as C5+ or synthetic crude oil for a synbit blend has been added. There is also the option of partial upgrading in Alberta to reduce viscosity to levels that may allow the upgraded bitumen to meet the viscosity specifications of existing pipelines with much lower levels of diluent.

It is prudent for prospective bitumen producers to investigate the economics, technical feasibility, and strategic implications of each of these options.

In very simple terms, the continuation of the market expansion for Alberta bitumen using existing project concepts, existing pipeline technology, and synbit diluent will likely mean high upgrading costs in an Alberta location, compared to the sale and upgrading of Alberta bitumen in US refineries.

One technically feasible option for the expansion of bitumen transportation from Canada would be construction of a new southbound pipeline for bitumen and the simultaneous construction of a northbound diluent-return line in the same project.

This concept is technically feasible and the diluent return would largely eliminate this constraint on bitumen supply development in Canada.

Any assessment of overall project economics should examine the upgrading costs in Alberta, the costs of handling the sulfur, and the possible export of sulfur by rail. The potential savings in upgrading costs on the US Gulf Coast vs. Alberta and the avoidance of sulfur recovery in Alberta may mitigate or even compensate for the pipeline cost of moving raw bitumen to the US Gulf Coast. Prospective shippers should carefully evaluate existing pipelines, any proposed pipeline project, and any new pipeline concepts that may emerge.

References

1. "Canada's Oil Sands, Opportunities and Challenges to 2015," National Energy Board, May 2004.

2. "Enbridge Launches US$600-million Crude Oil Pipeline Proposal to Provide Enhanced Access to U.S. Markets," Enbridge Press Release, Oct. 6, 2003.

3. "Annual Report 2003 to Parliament," National Energy Board, March 2004, p. 21.

4. "Assessing New Markets," Enbridge presentation by Richard Bird, June 25, 2003.

5. "Investment Community Presentation," Enbridge, May 2004.

6. Notes for remarks by K.C. Williams, senior vice-president, resources division, to the Imperial Oil investors meeting, Toronto, Dec. 2, 2003.

7. "Canadian Oil Sands Trust announces update to Syncrude's Stage 3 project construction schedule and capital cost estimate," Canadian Oil Sands press release, March 2004.

8. "BA Energy Heartland Upgrader," application submitted by BA Energy Inc., Calgary, to Alberta Energy and Utilities Board, May 2004.

The author

David J. Hawkins ([email protected]) is president of Hawkins Gas Consultants Ltd., Calgary. He joined the Canadian affiliate of Purvin & Gertz Inc. in 1976 where he worked until 1997. During 1997-99, he was a consultant to Alliance Pipeline. Hawkins holds a doctorate in control systems from the Victoria University of Manchester (England), a BASc in engineering science, and MASc in chemical engineering from the University of Toronto. He is a registered professional engineer in Alberta and Ontario.