Public resistance narrowing LNG options in North America

Public acceptance is critical for the approximately 45 LNG regasification terminals being proposed for North America.

Local public opposition to the construction of LNG terminals already has caused several proposed projects to be cancelled.

In March, TransCanada Corp.'s and ConocoPhillips's Fairwinds LNG terminal in Harpswell, Me., and Calpine Corp.'s Samoa Point LNG project in northern California succumbed to local opposition. By contrast, companies proposing to build LNG terminals in the Gulf of Mexico generally have met with less opposition than their competitors proposing New England or California sites.

But project developers should be aware that a risk-reward assessment of these respective projects suggests that companies should not base their decisions for project sites on the likelihood of public acceptance alone.

Frosty reception in New England

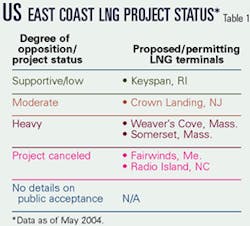

Of the six LNG terminals that have been proposed on the East Coast, two have been cancelled and two proposed in Massachusetts are meeting heavy opposition (Table 1).

The Fairwinds LNG terminal in Maine was blocked by Harpswell residents on Mar. 9, when they rejected, 55-45%, a referendum on having the terminal built. Despite job creation benefits (50 permanent jobs), fiscal benefits ($8 million in government revenue), and support from Maine Gov. John Baldacci, Harpswell rejected the proposal primarily out of concern about the scale of the project relative to the size of the town and its effect on local fisheries.

The proposed Massachusetts terminals in Fall River by Weaver's Cove Energy LLC (owned by Poten & Partners) and in Brayton Point by Somerset LNG LLC have met similar opposition. The public in Fall River already was voicing opposition during the public scoping period (officially closed on Jan. 30), due to the proposed project site of Weaver's Cove in a residential neighborhood, the narrow bay that the tankers would have to navigate, and the potential for bridge closures with tanker traffic.

Moreover, hundreds of residents sent a form letter to the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission expressing their opposition and requesting the public scoping period be lengthened so that they could "familiarize" themselves with the project report for Weaver's Cove. The form letter included boxes for the senders to identify themselves as "voters" and "taxpayers." Among the opposition of other prominent local officials, the mayor of Fall River became involved by sending a protest letter to the Weaver's Cove CEO, in which the former accused the company of trying to speed up the regulatory process behind the backs of the town's citizens and requested that the company withdraw its proposal.

The local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that oppose the Weaver's Cove project have formed a coalition to oppose any siting of LNG terminals in Narragansett Bay, including Somerset LNG's proposed terminal near Swansea, Mass. The Coalition for the Responsible Siting of LNG Facilities has given support to the Swansea selectmen as they have begun drafting an opposition letter to be sent to local and state officials. However, the coalition does not seem to have raised opposition to Keyspan Corp.'s intentions to upgrade its storage tank in Providence, RI, so that it can be filled from offloading tankers.

California daze

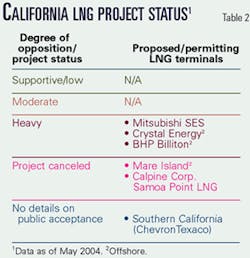

The projects proposed in California, even those sited offshore, have met fierce opposition from local residents and NGOs (Table 2).

In mid-March, Calpine Corp. cancelled its planned terminal in the town of Eureka in northern California after local residents and officials voiced strong opposition to the project during a well-visited public meeting. Despite the positive economic impact the proposed terminal would have had for this community of 26,000, the sheer size of the project (the two storage tanks would have stood almost three times as high as the tallest town building) was a primary concern.

The projects proposed in southern California are also targets of public antipathy. The Mitsubishi Corp.-owned Sound Energy Solutions' proposed terminal for Long Beach has become the target of public opposition by environmental NGOs, such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club. One strategy that Greenpeace has undertaken to oppose the project is to flood FERC with a form opposition letter signed by individuals during the public scoping period. Over 550 copies of this letter were received by FERC on Feb. 19 and have been posted on its web site, where submitted documentation from companies and letters from the public are published.

Two other projects, Clearwater Port (Crystal Energy LLC) and Cabrillo Port (BHP Billiton Ltd.), proposed near the town of Oxnard in southern California, have had to contend with accusations of social bias in addition to the more-often-cited security and environmental concerns raised by the public. Local activists have pilloried the companies with claims of choosing project sites in largely Latino and blue-collar Oxnard because they expect to have mild public opposition compared with more-affluent communities. The large opposition also has compelled the city mayor, Manuel Lopez, to weigh in, and he has become one of the projects' most vocal critics.

Sanguine Gulf Coast public

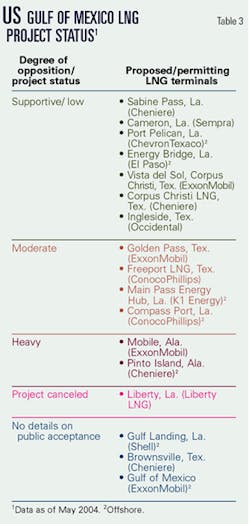

In contrast to the public relations difficulties experienced by proposed projects in New England and California, projects in the Gulf of Mexico region often have received a warm welcome and widespread support (Table 3).

The exceptions to this have been ExxonMobil Corp.'s and Cheniere Energy Inc.'s proposed terminals in the area around Mobile, Ala., where public misgivings have led to the suspension of development of the projects and the pursuit of more-promising sites in the gulf area.

With Cheniere's Pinto Island site, local citizens were concerned primarily with the site's proximity to a jail and historical-cultural sites. Public surveys have shown that a "large majority" of the public is opposed to an LNG terminal in the greater Mobile area.

The strong public opposition to the Mobile sites is in stark contrast to public reception of projects proposed in Texas and Louisiana. When companies have proposed sites in these states, they have encountered minimal opposition and have usually acquired immediate local advocates, who propound most of all the projects' economic benefits. Usually the projects have gained the support of state and local civic leaders, such as the state governor, congressional representatives, town mayor, city council members, police jury, port authority, and other governmental departments. Company representatives have encountered welcoming citizens at their first public meetings; one company representative even spoke of an "atypical" supportive response from residents when he presented a proposed project in Louisiana.

An encouraging sign for energy companies with proposals in Texas is that public support has remained strong even when international NGOs have tried to stir up opposition against them. One example of this was in February when the Paper Allied-Industrial, Chemical & Energy International Union sent about 4,000 fliers to Ingleside, Tex., residents to inform them of the safety dangers of LNG terminals. The town is located in an area where ExxonMobil, Cheniere Energy, and Occidental Petroleum Corp. are each proposing LNG terminals. In spite of this intervention by the international union, local support from officials and citizens alike has remained solid for all of the projects.

Other North American terminals

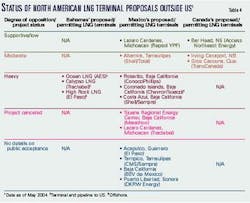

In addition to the approximately 30 LNG import terminals that are being proposed in the US, 16 other terminals have been proposed—Mexico 11, the Bahamas 3, and Canada 3.

These "other" North American terminals have experienced varying degrees of public opposition (Table 4), but the proposed Mexican and Bahamian projects have been particularly prone to fierce local opposition.

The proposed sites outside the US where opposition has been minimized are typically brownfield sites in heavy industrial zones, such as Repsol YPF SA's project at Lazaro Cardenas in Michoacan, Mexico, and Access Northeast Energy's project at Bear Head in Nova Scotia.

Public opposition has been strongest in Mexico and in Florida, where pipelines from the Bahamian projects would be sited. Environmental NGOs, such as the Sierra Club, Cry on the Water, and Stop the Pipeline oppose the three Bahamas-Florida projects because of the negative impact they claim such a pipeline would have on the coral reef, sea grass, and other marine life. Their ire was further aroused when Tractebel SA damaged coral reefs while conducting geotechnical drilling tests related to the firm's Calypso LNG pipeline in March. The NGOs have been joined by coastal Florida townships, such as Dania Beach, Lake Worth, and Palm Beach Gardens, to oppose the pipelines.

Despite the projects' relatively late stage in the permitting process, mounting political pressure has forced Florida Gov. Jeb Bush's cabinet to advocate a "go-slow" approach in the development of the projects.

Proposed terminals in Mexico are particularly vulnerable to becoming "lightning rods" for political gamesmanship and public opposition. The tendency of Mexican groups to pursue politically motivated attacks against projects proposed by foreign investors is most clearly seen in the recent contention that Mexico's two leading opposition parties, the PRD and the PRI, have posed to ChevronTexaco Corp.'s proposed terminal off the Coronado Islands.

Leaders from these parties have claimed the project violates Mexico's sovereignty and have called ChevronTexaco "devil-like." Public opposition to the project has been mounting since a local NGO released a report in 2003 that classified the Coronado Islands as a high-priority conservation site and claimed that construction of the LNG terminal would inflict permanent damage to the "cultural and historical heritage" of the area.

ConocoPhillips's and Marathon Oil Corp.'s proposed terminals in Baja California have succumbed to insurmountable bureaucratic barriers on the heels of strong public opposition. Marathon dropped its plans when its land lease was expropriated by the Baja California government, which claimed that Tijuana's municipal development plan does not envision gas terminals, but rather housing, businesses, tourism, and preservation.

As if the existing bureaucratic hurdles for LNG project development in Mexico were not enough, local opposition groups have in some instances received support from other environmental NGOs, such as Greenpeace, to block the projects.

Concluding thoughts

History is important to understand the role of public opinion in large infrastructure projects such as LNG terminals.

Much of the political and public opposition to projects in Baja California has to do with the region's historically tenuous relationship with US energy companies. In fact, one of the most outspoken and influential critics of ChevronTexaco's Coronado Islands proposal is Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, son of former President Lazaro Cardenas, who nationalized the oil industry in 1938 (and in the process expropriated the assets of 17 international oil companies).

Conversely, the mild public reaction towards companies' LNG terminal proposals in the Gulf of Mexico region likely results from its history as a major gas producer and the untainted safety record of the Lake Charles, La., LNG facility.

It certainly appears that communities in the northeastern US (acutely aware of large-scale disasters à la the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks or the Three Mile Island nuclear plant incident) and California (often preferring renewable energy resources, such as wind and solar energy) are more resistant than those along the Gulf of Mexico.

However, companies should not base their decisions for project sites on the likelihood of public acceptance alone. The plethora of new LNG terminal proposals in the Gulf of Mexico could create overcapacity in this region and burden the outlook for pipeline takeaway capacity there, while failure to site LNG import terminals in California and the northeastern US could leave these markets underserved. Hence, there is increased risk of having proposed import facilities in the two latter regions rejected by concerned communities, but the potential reward for successful LNG companies also is much greater.

Local citizens and NGOs usually oppose the construction of an LNG terminal because of security or safety concerns, environmental disruptions, trafficking of large tankers, aesthetic impairment, social equity concerns, and falling property values. In addition, national and international NGOs and unions may attempt to spark public opposition through advocacy campaigns.

The LNG industry can work to address and counteract these issues. Public acceptance, however, is in the long-term economic interests of the project development companies as well as responsible government officials who are concerned about legitimacy among all stakeholders.

The authors

Sara Banaszak directs PFC Energy's North American Gas Policy Service and advises the firm's clients on international and North American natural gas strategies. She combines a background in oil, gas, and interfuel competition with LNG market and policy expertise to provide qualitative and quantitative analysis related to competitive positioning in the global natural gas business. Her focus on the LNG industry includes global trade, including contract and pricing structures, and North American-focused investment, terminal development, and regulatory issues. Banaszak has advised Asian LNG buyers on gas importing strategies, multinational companies on gas marketing options, and multilateral organizations on how to accelerate natural gas investments. She holds a masters in applied economics from the University of Hawaii and a bachelors in international relations from the University of Pennsylvania.

Franz Traxler is a staff member in PFC Energy's Gas Group. He previously worked in the risk management division of the US Overseas Private Investment Corp. and as a mergers and acquisitions consultant. Traxler holds an MS in foreign service from Georgetown University.