Rebutting the critics: Saudi Arabia's oil reserves, production practices ensure its cornerstone role in future oil supply

Recent media reports have suggested Saudi Arabia may not be able to supply its share of the world oil demand for the near future.

"Experts" have argued in major US newspapers and at energy forums that not only are the kingdom's petroleum reserves overstated but also that the kingdom has rejected necessary foreign investments in its energy sector and that poor production practices have damaged its oil fields.

Are these allegations true? Are there problems in the kingdom's oil fields? Can the kingdom meet the growth in demand for additional production? These questions require explicit answers. Unfortunately, the policy of years of withholding technical information has allowed such misconceptions to flourish even though they have little substance in point of fact.

As of 2004, Saudi Aramco has established its oil reserves at 260 billion bbl, which is approximately 25% of the world's proven oil reserves. Some reports have speculated that these figures may be drastically inflated.

In February, for instance, the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas suggested that the kingdom's oil reserves might be only 180 billion bbl. Others have speculated that the kingdom's increase in reserves by almost 100 billion bbl in the early 1980s was unsupported by technical assessments.

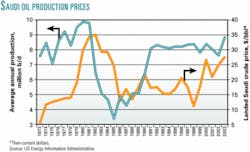

The fact that oil prices had doubled between the late 1970s and early 1980s and are still three to four times the oil prices of the early 1970s in 2000 dollars was not factored in by many of these analysts.1

Proving estimates

In fact, the kingdom's oil reserves estimates are based on Society of Petroleum Engineers, American Assocation of Petroleum Geologists, and World Petroleum Congress definitions, conventional petroleum engineering practices, state-of-the-art reservoir simulation, and conservative economics. While these definitions differ from the more-stringent US Securities and Exchange Commission requirements typical of smaller, shorter-life accumulations, they are the same definitions utilized throughout the world by countries holding giant oil and gas resources.

During my own tenure at Saudi Aramco as the senior executive in charge of exploration and production, we undertook numerous initiatives to improve the accuracy and reliability of these estimates. We drilled, cored, and logged numerous key wells in every active field and reservoir and surveyed the most significant oil fields with complete 3D seismic coverage. Massive simulation models were constructed to consolidate this and huge archives of geological and production data and to support our understanding of the reservoirs. These simulations spanned decades of performance history on a zone-by-zone and well-by-well basis. Over the years, these models have been updated annually and have confirmed our predictions of reservoir performance and our calculations of reserves and oil recoveries.

Future potential

As to the possibility of future reserves additions, there are extensive reservoir and source rocks in Saudi Arabia spanning the Paleozoic through Cenozoic time scales. These must surely offer additional opportunities for oil and gas discoveries. The size of such fields, however, will be substantially smaller than current proven accumulations. This is due to the seismic reconnaissance and grid coverage that already has spanned the most promising regions of the kingdom in search of giant oil and gas structures. While there may yet be many undiscovered oil and gas accumulations with millions of bbl of reserves, they are likely to be of limited acreage and vertical closure by Saudi standards.

Whether the exploration for such accumulations will add billions of bbl of future reserves will depend on the prevailing economics and government policies within the kingdom. The more liberal the policies, the more commercially viable will exploration and development become in future decades.

In terms of immediate additions, the enhancements to conservative oil recoveries in undeveloped reservoirs will be more important than new field discoveries. Furthermore, if the past is any indication of the future, advances in technology are bound to reduce the cost of recovering marginal discovered resources, thus adding to the reserves figures.

Given the fact that the discovered but undeveloped Saudi reservoirs make up about 130 billion bbl of the kingdom's total reserves, the addition of new proven reserves through future reservoir developments is a foregone conclusion.

A 10% increase in recovery estimates for these reservoirs alone would generate 13 billion bbl of additional reserves. This is significant but clearly not sufficient to replace the high rates of Saudi production, currently averaging 3 billion bbl/year. On the other hand, at the current production rates and with an existing reserves base of 260 billion bbl, the issue of future reserves replacements will not be a concern until well beyond 2020.

Production capability

The supposed inability of Saudi Arabia to meet its production targets in the next few years also requires discussion.

At the current depletion rate of 3 billion bbl/year, which represents 2.3% of the remaining 130 billion bbl of proven developed reserves, this concern is debunked by simple mathematics. Utilizing existing technology and sound engineering analysis, my staff and I were confident that Aramco could sustain even higher rates of production, if necessary.

From an economic point of view, however, the cost of production must rise to meet increasing production complexities that evolve with reservoir maturity. Although the kingdom's oil reserves are immense, they are not infinite and they do include a broad spectrum of reservoir qualities. As production increases to include lower-quality or mature reservoirs, the cost of production will increase accordingly.

Such steady cost escalations have been anticipated for a long time. For example, the majority of the Saudi carbonate reservoirs under production are supported by water injection. As their depletion advances, high resolution reservoir simulations have shown that the flood fronts will disperse within the numerous oil zones. The produced oil will inevitably commingle with increasing volumes of injected water.

Workovers, recompletions, and new horizontal laterals will delay the water ingress into the producing wells for an extensive period of time. Eventually, however, this becomes unavoidable. At high water cuts, widespread artificial lift is virtually inevitable. This in turn will require the processing and disposal of very high volumes of produced water. These maturity-related transitions may not occur for years to come, but they are ultimately unavoidable and have obvious economic implications.

The offshore clastic reservoirs do not have water injection, but they do have complex geological configurations and matching variability in aquifer support. The main sands benefit from very dynamic aquifer support, while stringer sands have less access and therefore less support from the aquifers. As the main sands are depleted, and in spite of careful reservoir management, major workovers will become necessary. These workovers will attempt to selectively tap into the remaining oil reserves. Since these are concentrated in the stringer sands, offshore artificial lift also will become inevitable in years to come. Whether gas lift or submersible pumps are utilized, given the size and scale of these operations, the investments will be substantial and will be accompanied by increasing operating costs.

Historically, such cost escalation has been deferred by developing new increments of oil reserves in parallel with maturing old fields and reservoirs. The past economic limits that have driven production declines in the older reservoirs in Saudi Arabia often have occurred at 20-25% depletion of the original reserves in sand and shale reservoirs and 35-40% in the carbonates. Technology and the addition of reserves may extend these production plateaus to higher levels of depletion, but this is unlikely to exceed a further gain of 10-15% under optimum economic considerations. On the other hand, once declines begin, highly commercial production still will extend for decades, as has been demonstrated by virtually every mature reservoir in Saudi Arabia.

Inevitably, the higher the production rates, the more the reservoir maturity is accelerated and the shorter the overall duration of the optimum economic production plateau. Front-end investments may be accelerated to achieve higher production plateaus, but these do not always give optimum oil and gas recoveries or full-reservoir life cycle economics. In Saudi Arabia, optimum economics depend on many variables, including the integrated economics of the full suite of reservoir developments, based on the maturity and status of all the available fields and reservoirs.

Increasing production

Based on these considerations, the kingdom can certainly increase its production to 15 million b/d, based on its existing reserves base. Sustaining such an elevated rate of production for decades, however, will be contingent on the future quantity and quality of reserves additions.

This in turn will be contingent on future technology developments and the then-prevailing prices for fossil fuels and energy substitutes.

In addition, it will be vital that such a rate increase is managed by a very large and highly qualified body of professional Saudi specialists. This is essential in order to avoid any misjudgments in reservoir or production engineering practices and to avoid undermining the available reserves base through inadequate reservoir management.

From a policy point of view, the decision to actually expand long-term production capacity is further complicated by the quality of long-term energy forecasts. For 2020, these estimates have varied in recent years, from 90 milion b/d to more than 120 million b/d of total oil consumption. With such disparities in projected demand, the risks of idle capacity or price collapse are very severe for major oil producers.

In an industry with project lead times that are measured in years and capital investments measured in billions of dollars, such inconsistencies are not conducive to firm, long-term facilities planning or capacity investments. In my own experience, the quality of the long-term forecasts has been the most severe impediment in the face of orderly capacity expansions and long-term project economics.

Production practices defended

Accounts in the Western press also have criticized Saudi oil production practices, claiming that they have damaged the reservoirs in some of the major oil fields.

Yet extensive studies have been undertaken over the years, some with direct assistance from ExxonMobil Corp. and the former Chevron Corp., in order to anticipate and prevent any such damages.

Quarterly production testing of virtually every active oil well in Saudi Aramco is conducted to forestall such problems. Breakthrough logging tools have been developed with Schlumberger Ltd., among others, in order to monitor all oil and gas reservoir zones. These have included developments to monitor zones shielded behind casing in order to capture the full spectrum of information required by the reservoir management teams. This process was institutionalized by the kingdom's Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources as far back as the early 1980s, when it demanded from the outset "first-class oil field practices" from Saudi Aramco.

If this commitment to prudence is adhered to in the future, the risks of reservoir damage will be minimized. On the other hand, if cost-cutting strategies and high-risk production practices are allowed to prevail, the consequences can be both devastating and sudden. Examples of such ill considered strategies might be an early shift to infield water injection patterns, a shift to dry crestal production strategies away from wet flank areas, and the heavy dependence on artificial lift without an adequate number of wells to tap into the various complex reservoir zonations.

Foreign investment

Finally, the Saudi government has been accused of being unwilling to accept foreign investments that would facilitate the development of its oil resources. Without such investments, it is argued, the kingdom's capability to satisfy the world's energy needs will be further eroded.

There are two problems with this argument. First, it ignores the fact that the government does actively pursue foreign investment in its economy, as exemplified by the downstream energy sector and the recent gas projects. Such investments have allowed the kingdom to focus on its upstream oil sector, which has not suffered for lack of financing.

Secondly, it ignores the reality that investments in the oil sector generate their own incremental revenues. These in turn finance additional investments. The only scenario where this process would not operate is the scenario where oil prices collapse and the returns on investments are inadequate.

In such circumstances, investments to increase production capacity would not be realistic, and the financing issue would be a moot point in any case.

The real issues

In the long term, the real issues in the oil industry are not the technical questions of Saudi Arabia's reserves or oil production capacity. Both of these issues have been managed well in the past and will continue to be addressed effectively in the future through advances in technology and engineering practices.

The real issue is whether there is a real willingness and commitment by both producers and consumers to achieve political and economic cooperation in addressing the unyielding economic imperatives imposed by the global energy markets.

Without such cooperation, energy-related volatility can only be exacerbated in the face of increasing demand for fossil fuels and the concentration of reserves in a few centers of operation.

Regardless of such future developments, however, it is a foregone conclusion that Saudi Arabia will remain the cornerstone of global energy supplies, and its role will be the key one in stabilizing the world's energy markets.

Reference

1. International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook 2002.

The author

Sadad Al-Husseini retired from Saudi Aramco on Mar. 1, as executive vice-president and a member of its board of directors. He joined Aramco in 1972, and his assignments have included various senior executive posts in its oil and gas exploration, production, and development operations. He was a special representative of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia in its natural gas negotiations from 2000 to 2002. Al-Husseini was a member of the Saudi Aramco Management Committee from 1992 until his retirement and was elected a member of its board in 1996. He also was a member of the Consolidated Saudi Electric Co. board during 2000-03 as well as holding other board positions in joint ventures and subsidiaries of Saudi Aramco. Al-Husseini graduated from the American University of Beirut with a BS in Geology in 1968. He obtained his MS in 1970 and PhD in geological sciences in 1973 from Brown University (distinguished graduate school graduate). He is an honorary member of the American Institute of Metallurgical, Mining & Petroleum Engineers and the Society of Petroleum Engineers.