Exxon-Mobil merger wins approval in EU, awaits US decision

null

Exxon Corp. and Mobil Corp. appear close to culminating an $82 billion merger that would create the world's largest publicly traded oil company.

The companies estimate that combining their firms into Exxon Mobil Corp. would save them $3 million/ day.

The consolidation would eliminate up to 9,000 jobs at the two firms. Headquarters will be at Exxon's Irving, Tex., offices, while Mobil's headquarters in Fairfax, Va., will house the company's marketing and refining operations.

Stockholders of both companies approved Exxon's acquisition of Mobil at annual meetings last May in Dallas.

Although the European Commission raised significant questions about how the merger would affect oil industry competition in Europe, the two companies agreed to enough divestitures to win EU approval.

The process has not been quite so easy in the US, however. The firms have been in negotiations with the US Federal Trade Commission staff for months.

The companies said they are continuing to talk with FTC staff on a daily basis and an agreement could come at any time.

EC approval

The European Commission approved the Exxon Mobil deal late in September after the two companies agreed to the largest divestments the EC had ever asked, although none of the agreed divestitures had been unexpected (OGJ, Oct. 4, 1999, Newsletter).

In its process, the EC, the executive body of the 15-nation European Union, worked closely with the FTC.

The EC required the companies to sell assets in certain market segments but let them retain other businesses in those segments.

Mobil will sell its 30% interest in the refining-marketing joint venture between it and BP Amoco PLC in Europe. Mobil will also sell its 28% interest in the German joint-venture marketing company Aral, which operates a large chain of gasoline stations, primarily in Germany.

The merged company will retain the retail fuels business of Esso in Central Europe. And, through the existing Esso brand, it will retain its current leading position in the European fuels market.

Both companies will sell part of their lubricant base oil manufacturing capacity in Europe. The merged company will retain a significant base oil manufacturing capacity there, however, and will remain the worldwide industry leader in this business segment.

Mobil will sell certain pipeline capacity serving Gatwick Airport outside London. The merged company will continue to sell aviation fuels to airports it currently serves, including Gatwick.

And Mobil will sell assets associated with its worldwide commercial airline synthetic turbine-lubricants business. The merged company will retain Mobil's worldwide synthetic aviation-turbine lubricants business, as well as Exxon's remaining aviation-lubricants businesses.

In European natural gas marketing, Mobil will sell its Dutch gas trading company, MEGAS, and Exxon will sell its 25% interest in Thyssengas, a gas distribution company in western Germany.

Mobil will reduce its voting rights in Erdgas M

Exxon and Mobil said they "remained committed to supplying high-quality products and services to their customers in the European market, and Europe would continue to represent a substantial portion of the merged company's upstream, chemical, and downstream businesses."

Strategies

EC regulators initially were concerned that the Exxon-Mobil deal would reduce competition in European exploration and production but quickly determined that would not be a problem.

In general, concentration of ownership in upstream resources tends not to reduce oil and gas production or increase oil and gas prices and is therefore not seen by regulators as detrimental to consumers.

With regard to consolidation of Exxon's and Mobil's European E&P assets, the EC said, "The 'supermajors' would still be facing competitive constraints from smaller oil companies, and countries on whose territory oil and gas is found have no incentives to let oil companies restrict production."

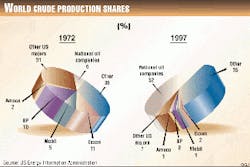

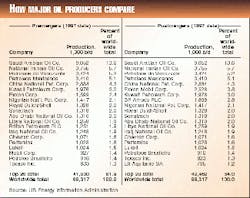

The global concentration of production that would result from the Exxon-Mobil combine is shown in Fig. 1 (at right). Despite this increased global market share, the merged firm would still rank sixth in global oil production, behind five key national oil companies (Table 1).

Once the issue of E&P market share was resolved, the EC's major concern became concentration in the German and Dutch natural gas markets, the lubricants market, in products distribution, and with certain joint ventures.

The commission was concerned about allowing Mobil to remain in the two European joint ventures for fear that the merged Exxon Mobil would not compete with BP Amoco.

And in Germany, Aral, Exxon, and the BP Amoco-Mobil venture would together account for more than 40% of gasoline sales.

BP Amoco is expected to buy Mobil's 30% interest in their R&M JV for $1.65 billion, about the value of the assets that Mobil contributed when the deal was established. And Mobil is expected to get around $1.08 billion for its interest in Aral, Germany's largest single gasoline marketer. Veba Oel GMBH, which owns 56% of Aral, reportedly is interested in buying out Mobil.

The merged company was also required to divest businesses selling base oils used to make lubricants, because its market share would have been more than 40%. Exxon agreed to sell its aviation lubricants businesses where the EC feared it might gain a dominant position.

At the request of Exxon and Mobil, the EC gave the companies extra time to complete the asset sales. The commission said the companies have a limited time to sell their assets but would not disclose its deadlines in order not to undermine the companies' bargaining positions.

FTC's concerns

With EC approval won, the FTC remains the only obstacle along Exxon Mobil's merger path. Exxon and Mobil initially expected to win FTC approval by mid-1999, but that date was later moved back to Oct. 1.

The FTC obviously has demanded divestitures that Exxon and Mobil have balked at making.

The Exxon-Mobil case is the largest in the FTC's history. The agency asked the two firms to submit documents that reportedly filled about 20,000 boxes.

If the FTC and the firms can't reach agreement, the agency could sue to block the merger. That option is considered unlikely as long as negotiations continue.

The commission primarily is concerned about oil industry concentration in light of the BP-Amoco merger and the pending Exxon-Mobil and BP Amoco-ARCO mergers.

From the beginning, analysts said Exxon and Mobil both were strong in the northeastern and mid-Atlantic US gasoline markets and predicted they would have to sell a number of service stations in those areas (Fig. 2). That is still believed to be the situation.

The FTC reportedly wants the firms to sell some gasoline terminals, ownership interests in pipelines, and one or more refineries. The agency is not only interested in the sale of properties: it wants to know who would buy them and how quickly.

Although the commission commonly requires companies to sell overlapping assets before it approves mergers, it reportedly may allow Exxon and Mobil to sell such assets after their merger, if those properties can be sold in a few months without difficulty.

If the FTC takes that route, it might require the firms to designate certain "crown-jewel assets" that a trustee would sell if the company fails to make the stipulated divestitures by a deadline. The FTC reportedly has determined that the merger wouldn't threaten competition in the US exploration-production sector.

Marketing

The commission's major concern appears to be gasoline station competition.

The two companies' largest overlap of marketing is in 11 northeastern US states, where together they have more than 15% of the branded retail stations. The combined firm also would have a dominant market share in parts of the Mid-Atlantic and California.

Attorneys general from northeastern states and California have been active in the FTC inquiry because of the gasoline competition issue.

It has been speculated that the two companies may be required to sell 1,000-1,500 gasoline stations. About a third are Exxon stations in states where Mobil's marketing network is stronger, and two thirds are Mobil stations in states where Exxon is strong.

The recent BP-Amoco merger could set a pattern in the sales. The FTC required those two companies to sell some stations, and in other markets where they did not own service stations, the firms had to give wholesale customers (jobbers and open dealers) the option of canceling their franchises and switching to other refiners for supplies (OGJ, Jan. 11, 1999, p. 30).

The FTC also might require Exxon and Mobil to license their brand names to independent service station operators in some areas. Dealers have complained they don't want to surrender the Exxon and Mobil brands, having already established businesses under those signs.

Retailers' concerns

Independent service-station operators also were concerned about another possibility.

They said the FTC, to ensure competition, was considering requiring Exxon and Mobil to sell large blocks of their company-owned service stations to a third oil company that is not already established in their strong marketing regions. The FTC reasoned such a sale would increase long-term competition in those regions, whereas, if the stations were sold piecemeal to a number of different companies, it would not.

The commission wants to entice another marketer into those regions, and several reportedly are interested. They include Citgo Petroleum Corp., Amerada Hess Corp., Tosco Corp., Tesoro Petroleum Corp., and Conoco Inc.

Exxon and Mobil station lessees in the Northeast have asked the FTC to give them the right of first refusal to buy their stations. They also want to be able to collectively negotiate with gasoline suppliers.

Some congressional representatives have tried to intervene for the dealers, although their views carry no official weight in the FTC inquiry. Eleven House of Representatives members wrote the FTC last month, urging that any divestitures be "fair and equitable" to service station operators.

They said, "It is our hope that any consent decrees established by the FTC will contain provisions that give any incumbent lessee dealer the right to buy the leased location and enter into a supply contract with a supplier of his or her choosing."

Refining

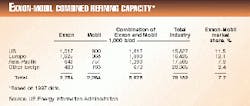

Combined, Exxon and Mobil have a global refining capacity of 5.876 million b/d (Table 2). About one third of this capacity is in the US, where the firms would have an 11.5% share of total US capacity.

The FTC may require Exxon and Mobil to sell a refinery or two and reduce their ownership interests in product pipelines.

Refinery sales are a tough issue, because the plants are multibillion-dollar assets and their sales could tilt the economics of the entire deal.

California is concerned that Exxon Mobil would control too large a share of the wholesale gasoline market there.

It was rumored that Exxon might be required to sell its 128,000 b/d Benicia refinery in northern California or at least place it on the "crown jewels" list to ensure that other assets were sold. Mobil owns a 128,000 b/d refinery at Torrance, in the Los Angeles area.

Clark USA Inc. reportedly was negotiating with Exxon to buy the Benicia refinery. But Exxon and Mobil were believed to have resisted selling a California refinery, because the production of that state's specialty gasoline is profitable, and the market is a difficult one for others to enter.

The two companies may have to sell one or more refineries in Texas and Louisiana. Both operate a refinery in Louisiana (Mobil owns 50% of a plant), and both have one in Texas.

Together, Exxon and Mobil would have 18-20% of US Gulf Coast refining capacity, a share worrisome to the FTC.

Some independent gasoline marketers have urged the FTC to let Exxon and Mobil keep their refineries as long as they keep supplying independent marketers.

Product pipelines could be a problem, too. Exxon has a 49% interest in the Plantation Pipeline Co. system from Louisiana to Washington, DC, while Mobil has an 11.5% interest in the competing Colonial Pipeline Co. that has a line stretching from Texas to New York City.

The FTC may believe the merged Exxon Mobil would have too much control over tariffs and pipeline space.

FTC viewpoint

The commission hinted this spring that divestitures would be required.

William Baer, director of the FTC's Bureau of Competition, spoke before the House commerce committee's energy and power subcommittee. He did not comment directly on the merits of the Exxon-Mobil merger but spoke generally about oil industry mergers.

Baer said the Gulf Coast refining market is critical to US competition because it supplies other parts of the country.

"It is vitally important for nearly all of this country east of the Mississippi to maintain a competitive Gulf Coast refining market. Similarly, we must ensure that the pipelines that deliver Gulf Coast product to these markets remain competitive.

"In the late 1980s, the commission acted to preserve competition in Gulf Coast refining in connection with Standard Oil Co. of California's merger with Gulf Oil Co. by requiring the divestiture of a Louisiana refinery and an interest in the Colonial Pipeline, one of the two pipelines that carry gasoline and other fuels from the Gulf Coast to southeastern and northeastern markets. When Shell Oil Co. and Texaco Inc. combined their refining and marketing, the commission required a similar pipeline divestiture."

He said the FTC is concerned about California refining markets because of tight supply situations there.

Baer said the FTC also is always watchful about gasoline marketing and has acted on at least 10 occasions over the past 20 years to protect consumers from petroleum mergers that would lessen competition.

"These were all cases where the commission believed that local or regional competition was sufficiently threatened to require enforcement action. We carefully tailored our relief to address the problems and restore any competition that would have been lost from the merger or other combination.

"If competition could not be preserved through divestiture, the commission has gone to court to block anticompetitive mergers in the petroleum industry in their entirety.

"What we have learned from these and other investigations is that competition is critical to this industry and that concentration, as well as increases in concentration-even to levels that the antitrust agencies call `moderately concentrated'-can have substantial adverse effects on competition."

Analysts' views

John Lichtblau, chairman of Petroleum Industry Research Foundation Inc., New York, said, "There's no doubt that the merger will come off. The only question is when."

Lichtblau said the US oil industry is highly competitive at all levels.

"No company has a dominant share of any segment of the market. This would still be true after the Exxon-Mobil merger.

"Equally important is the US market's open access to the global oil market. Currently, over 50% of (US) crude oil requirements and over 10% of (US) refined products requirements are imported, and these shares move continuously with supply-demand changes.

"Even in the most concentrated oil industry region-Texas and Louisi-ana-the Exxon-Mobil combined share of refining capacity is only 20% of the area's total."

He added that the 20% is deceptive, because, "The Gulf Coast is an open market for cargoes. It's part of the world market, exporting 350,000 b/d of products last year and importing 100,000 b/d. So the 20% share of refining capacity doesn't give you the whole picture."

Lichtblau said that, although the West Coast market is less competitive, the Exxon and Mobil refineries there represent a much smaller slice of the market. "The FTC could justify not touching those refineries."

He said the companies are likely to be forced to sell some northeastern gasoline stations, but even their marketing concentration there is misleading. "Geographically, these are small areas with high concentrations of population and many gasoline stations. It's easy for consumers to drive to another gasoline station if they think the prices at one are too high. For instance, New Jersey has 61 stations per 100 sq miles, while the national average (excepting Alaska) is 6 per 100 sq miles.

Philip Verleger, of PKVerleger LLC, Concord, Mass., said, "The FTC is wasting a lot of taxpayer resources on this. After the merger, there will be sufficient (oil industry) competition everywhere, so the Exxon-Mobil merger doesn't matter, either at the retail level or the refining level."

As to divestitures, Verleger predicted the two companies "will do whatever they have to do in order to complete the merger."