Oil, gas in FSU Central Asia, northwestern China await development

Central Asia today represents one of the world's last great frontiers for geological survey and analysis, offering opportunities for investment in the discovery, production, transportation, and refining of enormous quantities of oil and gas resources.

Central Asia is rich in hydrocarbons, with gas being the predominant energy fuel. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, especially, are noted for gas resources, while Kazakhstan is the primary oil producer.

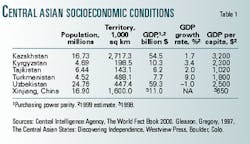

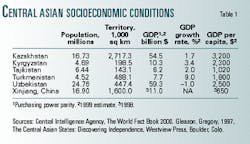

Home to more than 70 million people in an area 45% of the size of the US (Table 1), Central Asia resources, which include 10 billion bbl of undeveloped oil reserves and 6.6 trillion cu m of natural gas, that await investment and development.

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan collectively are considered to have the largest potential for hydrocarbon development outside of Russia in the former Soviet Union (FSU).

Neighboring Xinjiang Uygur Auton- omous Region, China, also has substantial hydrocarbon potential, al- though previous projections of reserves were grossly overestimated. Trade has grown rapidly between Xinjiang and the FSU Central Asian nations.

Leaders in the energy-rich but capital-poor republics want to introduce capital, technology, machinery, and science from abroad in order to expand their national energy sectors, improve efficiencies, and escape Russian domination, which continues to hamper development in a number of ways. For example, the only existing, viable export routes from the area lead into and out of Russia. These nations will not be free from Russia's economic stranglehold until their lucrative energy resources can be developed and transported to Europe-while avoiding Russian territory-and, ultimately, to Asia, the world's fastest-growing region.

Significant opportunities now exist for foreign participation in the FSU Central Asia and northwestern China oil and gas industries, given recent efforts by the local governments to stimulate private investment in refinery modernization, pipeline construction, and enhanced oil recovery. Assistance is generally needed in technology, capital, and management.

This region will require billions of investment dollars to renovate its oil and gas industries this decade and beyond. The area is plagued with low recovery efficiencies in production and utilization, outdated equipment and technology, and severe transportation bottlenecks. Priority will be given to the development of oil and gas reserves having large volumes and high-grade deposits, low production costs, and economically viable operations.

Russia's influence

Despite the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia still exerts economic influence over its "near abroad" neighbors, with much domination linked to energy and energy products. Oil and gas accounts for about half of Russia's foreign exchange earnings and contributes significantly to that nation's economy. Consequently, Russia is determined to maintain its grip on the lucrative Central Asian energy resources.

For example, Russia wants the 150,000 sq mile Caspian Sea to be designated as a lake, requiring that its resources be cooperatively developed by the states surrounding it.

Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, in contrast, have insisted that the Caspian be treated as a sea under international maritime law, thus providing each coastal state the exclusive right to develop a discrete area. Iran and Turkmenistan support Russia's position (OGJ, May 28, 2001, p. 66).

Another area of controversy between Russia and its neighbors is oil and gas transportation. As long as the export routes from Central Asia remain burdened by Russian influence, the oil-rich re- publics in the region will have difficulty realizing their full production capacity.

Breaking free

Consequently, the Central Asian FSU nations and Xinjiang have established significant ties with the West, and the five FSU nations are members of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank.

In the years ahead, the world's oil and gas industry will, without question, be influenced greatly by exploration and development activities in Kazakhstan, Turk- menistan, Uzbekistan, other independent FSU Central Asian republics, and Xin- jiang.

Today oil and gas companies worldwide are closely monitoring energy activities there in order to accurately gauge their total impact on international commodity markets.

While it may take many months, or even years, for Central Asian FSU states and Xinjiang to build and expand their oil and gas industries, an enormous hydrocarbon base and a strong possibility for new discoveries will continue to lure foreign investors seeking to establish long-term positions. Those companies willing to take on many of Central Asia's challenges may be well rewarded for their patience and commitment.

Pipelines

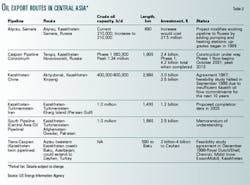

A number of pipeline projects to carry Central Asia's resources west are under way or have been proposed. In general, there are three principal export routes out of Central Asia: through Russia and the port of Novorossiysk, through the Caucasus (Georgia or Azerbaijan), or via Turkey and Iran. Routes through Russia involve the Caspian Pipeline Consortium's plans for transporting Tengiz-Korolevskoye oil to Novorossiysk on the Russian Black Sea or Azeri oil from the Caspian Sea to the north.

CPC currently is laying a new 450-mile pipeline section to Novorossiysk. Delivery of first oil is expected this year.

Routes through Transcaucasia would take Azeri oil to Turkey through either Georgia or Nakhichevan. Those to the south generally involve transport to the Turkish cities of Midyat and then Ceyhan or, alternately, to Sivas and then to Ceyhan. All three principal routes are fraught with problems and concerns, including the substantial costs for new pipeline construction and development of related infrastructure.

Kazakhstan wants to cut reliance on Russian crude and ultimately hopes to construct an oil pipeline from western to eastern Kazakhstan, ending a costly ex- change program in which most Kazakh oil goes to Russia.

Kazakhstan is negotiating with Turkey and Iran for construction of an oil pipeline (opposed by the US) to link the country with Europe, and US-backed routes (opposed by Iran) have been proposed through Georgia or Armenia (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Iran has frequently accused the US of trying to convince Turkmen officials to have their gas pipeline pass through Azerbaijan and Georgia rather than Iran and Turkey.

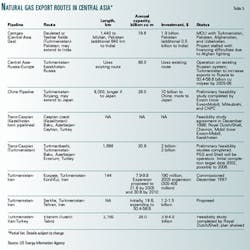

The most important pipeline being proposed in Turkmenistan, however, is the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline linking the country, via the Caspian Sea, to Azerbaijan through Georgia and then on to Turkey.

Similarly, other Central Asian republics are working with foreign investors to build pipelines and establish new oil and gas flows to European markets via Turkey, Iran, Iraq, or possibly Georgia.

Turkmenistan and Iran opened a 125-mile pipeline connecting the Korpedzhe gas field in western Turkmenistan to northern Iran in 1997. Other routes being considered for Turkmen gas include lines to Pakistan, via Afghanistan, and eastward to China and Japan.

China has expressed some interest in the latter project, as it will play a significant role in transporting Xinjiang's natural gas to the consumers in eastern and southern China. Japan, in turn, is promoting the pipeline in order to supplement its deficient gas supplies later this decade.

While cost estimates for the pipeline are astounding-$11.8-22.6 billion (depending on the route)-Mitsubishi Corp., China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), and other interests continue to plan and design what would be one of the largest-infrastructure projects in the world.

Uzbekistan, also hampered by the Russian pipeline monopoly that restricts the country to exporting most of its natural gas to its immediate neighbors, is considering several new pipelines (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Kazakhstan

By far the largest and the second-most populous Central Asian country, Kazakh- stan has a 3,000 mile border with Russia to the north and a border with China to the east.

Kazakhstan possesses the region's largest hydrocarbon industry-65 tcf of natural gas and an estimated 1.1 billion tonnes of proven reserves of oil, earning it the nickname: "the new Kuwait." In 1999, Kazakhstan accounted for 65.9% of the oil and 11.2% of the gas extracted in FSU Central Asia.

No nation in FSU Central Asia has done more to woo foreign investors than Kazakhstan, reflected by the country's highest credit ranking in the region. International oil companies have found the investment climate in Kazakhstan relatively favorable since its independence because government officials have expended tremendous effort to create sufficient investment legislation and a national energy policy, while eliminating bureaucratic bottlenecks common to many other former Soviet republics.

President Nursultan Naszarbayev has maintained a keen interest in all negotiations.

Privatization, or more precisely, "corporatization"-the adoption of western managerial and accounting practices-is proceeding today in Kazakhstan in all aspects of the energy industry, though slowly and incompletely. The pace of these efforts quickened during 1995-97.

Dozens of companies from all over the world have formed, or are now forming, joint ventures in the country. The largest are multinationals such as US-based Chevron Corp., with investment of $20 billion in a 50-50 JV interest in Tengiz- chevroil to develop Tengiz oil field. Other stakeholders are Kazakhoil National Oil & Gas Co. (KazakhOil) 20%, ExxonMobil Corp. 25%, and LukArco BV 5%. Another key multinational focused on Kazakhstan is ExxonMobil Corp., whose Mobil Corp. predecessor purchased a 7.5% share in the consortium planning to build an oil export pipeline to a new oil terminal near the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiisk.

In both oil and gas, the Kazakh government has been "corporatizing" enterprises on a case-by-case basis, with the process now almost complete. KazakhOil, formed in 1997, owns all government stakes in the country's oil enterprises and JVs, and it has inherited the country's oil industry debt-$1.3 billion-as well.

Turkmenistan

Leading the Central Asian countries' growing natural gas sector, Turkmenistan, already a net gas exporter, possesses the eighth largest proven gas reserves (BP PLC's 2000 statistical review) with an added potential that has scarcely been touched.

More than half of its output of 80 billion cu m/year of gas comes from supergiant Dauletabad field in eastern Turkmenistan.

A desert country and the least populous one in Central Asia, Turkmenistan contains 5% of the FSU's proven natural gas reserves, second only to Russia. Although Turkmenistan's oil fields contain large volumes of untapped associated gas, development prospects will remain dim until the country establishes viable transport routes to bring that gas to markets in Europe, the Middle East, and eventually, China.

Turkmenistan produced only 7.4 million tonnes of oil in 1999, down from the peak level of 16 million tonnes 20 years ago.

While Western oil and gas companies are eager to participate in the tremendous investment opportunities in Turkmenistan, a combination of economic, political, cultural, and historical factors currently are hindering some prospects for significant JV development.

Uzbekistan

The most densely inhabited Central Asian country, Uzbekistan is the geographical center of the region and the hub of its transport and electrical power systems. Like Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan has substantial oil and natural gas potential, and its production of oil and condensate has doubled in the last few years, virtually eliminating the need for imported fuel for power generation. Today Uzbekistan is becoming a reliable petroleum exporter.

Uzbekistan's state oil and gas holding company Uzbek- neftegaz has em- barked on a number of priority projects with international companies and lending agencies. Since 1991, Uzbek- neftegaz has held negotiations with a large number of multinational oil and gas companies, including Elf Aquitaine SA (now part of TotalFinaElf SA), Enron Corp., and OAO Gazprom.

Uzbekistan currently is seeking investments in several particular areas:

- Exploration and development of new hydrocarbon reserves.

- Development of oil reserves located beneath gas caps.

- Redevelopment and secondary recovery programs in selected producing fields.

- Development of previously identified oil and gas fields.

Uzbekistan has made strong efforts to attract foreign capital and technology for resource development in cooperation with Uzbekneftegaz.

Kyrgyzstan

Mountainous and bordering China, Kyrgyzstan has the smallest energy industry of the five. However, of all the FSU republics, it has made the most progress toward building a democratic political system and is working to bring its legal and normative acts into conformity with international standards.

The government has announced plans to privatize Kyrgyzneft, the national oil company, and to allow privately owned companies to operate in the oil sector. It is also actively seeking foreign investment to boost hydroelectric power capacity and improve transmission line quality.

Tajikistan

Like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan is a mountainous nation bordering Afghanistan and China.

It is the smallest republic in Central Asia and has the lowest per capita gross domestic product. It suffers from constant political turmoil, civil strife, and insufficient economic reform.

Tajikistan's oil and gas industries are limited in size, and all exploration, production, and drilling activities are carried out by the state-controlled Tajikneft organization.

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, an autonomous region in the northwestern corner of China, is one sixth of the total land area of China and the largest provincial region. Xinjiang is a strategically sensitive area, bordering Russia and Mongolia to the north and Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to the west.

The Junggar basin, which lies in Xinjiang's northern section, contains one of China's largest producing oil field complexes, Karamay. Surface geology studies have shown that the basin's several structural units are all prospective for oil and gas.

Since 1955, when the first commercial oil discovery was made at Karamay, dozens of oil fields have been developed in the vicinity. Combined, the Junggar, Tarim, and Turpan basins represent Xinjiang as a major petroleum-producing province in China. Together these basins provide nearly 20% of the nation's total crude oil output.

Although present and projected oil production exceeds current and projected oil consumption in Xinjiang, national policies require the province to ship 50% of its crude oil production to other provinces within China, resulting in an oil deficit in Xinjiang itself. Regional cooperation is thus important to alleviate potential future energy shortages in the area.

Chinese environment

China considers environmental protection as a fundamental national policy while encouraging reasonable economic development activities. While energy demand in Xinjiang will increase significantly in the coming decades, im- proved conservation measures and the adoption of new energy-saving technologies will help reduce energy intensity, or the use of energy per unit of output.

Xinjiang has established these major energy and environmental strategy goals:

- Emphasize equally energy exploitation and energy conservation.

- Improve the energy supply mix to provide greater emphasis on electric power generation.

- Speed up the development of hydropower and natural gas in order to increase the proportion of clean primary energy.

- Enhance reliable energy management practices and promote technical innovation for energy-consuming and energy-saving technologies.

- Further develop renewable energy resources.

- Raise the efficiency of energy conversion.

- Rationalize prices of energy.

- Alleviate atmospheric pollution caused by direct, extensive coal burning.

China has implemented these policies for the last decade throughout the country, and they have proven effective in terms of environmental protection and energy development. However, despite any additional adjustments anticipated, there will not be substantial or fundamental changes in China's overall energy structure for at least 15 years. The country will remain for many years a largely coal-based economy.

Area cooperation

Improvements in political relations among Central Asian countries and historical ties with many neighboring nations have raised considerably the prospects for bilateral and multilateral energy relations within Central Asia. Opportunities exist for region-wide cooperation in development, transportation, and trade. Centuries-old cultural and ethnic ties strongly influence cooperation in this area.

Growing demand for energy resources and their products in China, combined with the substantial resources and a need for capital in Russia, suggest a favorable climate for joint development activities.

With China and Russia, however, energy megaprojects, such as the proposed Kazakhstan-Xinjiang oil pipeline, will encounter numerous obstacles: an apparent slowing of Japanese investment in resource development projects, conflicting and competing strategies, inadequate infrastructure, and differences in political ideologies throughout Central Asia, the Middle East, and the US.

Turkey, Iran, and China are seeking allies in Central Asia, while Russia is exerting increasing political influence on new pipeline development from Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

Small and medium-scale JVs have a more reasonable chance of coming to fruition in the region, as individual companies are selecting projects in which they have extensive experience, a strong desire to participate, or a comparative advantage in the development.

Looking ahead

FSU Central Asia and Xinjiang have initiated comprehensive macroeconomic stabilization and reform programs to combat the political and energy instability, periods of high inflation, and reduced industrial output that the FSU nations suffered early in their newly independent stage.

Countries such as Kazakhstan that initiated reform policies early in their transition have experienced significantly reduced inflation and a resumption of growth. Maintaining growth, checking inflation, and proceeding with structural reforms are their priorities. Those less advanced in their transition and still facing decreased economic output, however, are more immediately concerned with achieving economic stability and introducing market forces to that end.

Transportation will remain the key bottleneck or facilitator of future hydrocarbon development in the region. On one hand, Turkey, Iran, and China are seeking allies in Central Asia, whereas Russia continues to exert (diminishing) political influence on most discussions concerning new pipeline development from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Those that control the oil routes out of Central Asia will impact all future direction and quantities of flow and the distribution of revenues from new production. The extent of new pipeline construction or refurbishment will also affect levels of foreign investment in the region.

While Western oil and gas companies seek energy investment opportunities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turk- menistan, Uzbekistan, and Xinjiang, a combination of economic, political, cultural, and historical factors currently are hindering some prospects for significant JV development.

Central Asia is predominantly a gas-producing region, but the potential for oil development is vast. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are the two major gas producers in Central Asia, although Kazakhstan also has significant gas deposits. Xinjiang is self-sufficient in gas.

Gas from the region, generally high in sulfur, must be treated before it can be transported through pipelines. Transpor- tation is a major problem facing most gas industries in Central Asia, especially in the FSU republics. The transportation network for gas, established during Soviet times, still reflects Russian priorities. Gas traditionally flowed through Soviet-built pipelines northwest to major processing centers in European Russia.

Oil is the second-most important energy resource with a significant export potential in the region. In addition to Kazakhstan's 1.1 billion tonnes, Uzbekistan has more-modest oil reserves (100 million tonnes), and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan produce very small quantities of oil.

Government and industry officials in Central Asia and Xinjiang are seeking foreign investment to renovate their oil and gas industries. Officials are also considering regional cooperation in oil and gas, given that energy shortages are already occurring throughout the area and that there is an uneven geographic distribution of energy resources among the countries and regions.

However, while Central Asia is poised to become a major world supplier of oil and gas, governments in the region generally emphasize energy self-sufficiency at the expense of developing new trading linkages.

Clearly, though overcoming infrastructure constraints is an important priority for the governments of the Central Asian FSU countries and Xinjiang, they will continue to be a focus of concern in the months and years ahead.

In the immediate years ahead, oil and gas companies around the world will continue to encounter an evolving industry in Central Asia, faced with complex issues such as increased competition for capital; environmental constraints; rising wages and labor costs; shifting centers of exploration, development, and processing; and unprecedented political change.

Priority investments

A number of priority investments are required in FSU Central Asia oil and gas industries:

- The economic evaluation of hydrocarbon deposits.

- Management training and skills, including engineering and construction project supervision.

- Advanced methodologies for hydrocarbon seismic reflection and refraction.

- The introduction of technology to improve the quality of natural gas liquids fractionation.

- Development of an integrated system for gas collection and utilization, including compressors for gas separation.

- Industrial gas drying and purification units and gas processing facilities.

- Resuscitation of fields previously considered spent but that still contain hydrocarbons that can be extracted with advanced technologies.

- Construction of product storage terminals and natural gas-fed petrochemical facilities.

- Refinery design, modernization, and construction.

- Pollution monitoring and control devices aimed at curtailing sulfur dioxide and fluorine particle emissions.

- Geological, geophysical, exploration, and remote-sensing technologies.

- Physical infrastructure and telecommunications networks and transportation equipment (notably tank trucks).

- Surveying equipment and technology for outer continental shelf studies.

Chasing foreign capital

All Central Asian states are trying to attract foreign capital to their critical oil and gas industries to stimulate economic expansion, and the revamping of regulatory and taxation systems has made investment more attractive.

Nonetheless, private capital inflows into the former Soviet republics have been modest to date-with a few notable exceptions. Some international hydrocarbon and financial firms have already invested spectacular amounts of money-and their reputations-in Central Asia. Several multibillion-dollar deals have already been made in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Other deals have turned sour or stalled.

Most private foreign-investor interest in Central Asia has focused on providing technology and expertise for the development of the region's potentially huge oil and gas fields. The biggest concerns to companies and international lending agencies considering investing in Central Asia and Xinjiang are unstable or unclear tax, currency, investment, and environmental policies that could jeopardize the investments, particularly as these relate to JV contract terms and conditions. Investors in oil and gas are specifically worried about securing reliable export options.

The environment

Environmental decisions are also playing an increasingly larger role in Central Asia and Chinese business decisions, in- cluding those related to energy. Investors are therefore seeking ways to reduce the risk while investigating potentially lucrative business opportunities.

To minimize risk, investors are advised to seek managerial control of the early, delicate years of a project and to examine and reexamine geologic and economic data to determine possible differences in definition, regenerating the data if necessary.

During contract negotiations, it is essential to define as accurately and precisely as possible the roles and contributions of the partners, i.e., how much capital each would put in and how management would be handled.

While uncertainties persist regarding political and legal environments in the Central Asian economies, oil and gas firms that establish at least a limited presence today in parts of Central Asia and Xinjiang will best be able to develop expertise and gain experience in the way business is conducted there, while waiting for investment conditions to improve.

The potential for further oil and gas discoveries in Central Asia is significant, and company strategists can no longer ignore the growth potential.

Xinjiang

In Xinjiang, priority areas for foreign energy investment include natural gas utilization, electric power plant construction, and oil and coal extraction.

While investor interest in Tarim basin oil and gas resources is keen, few joint ventures have been established to date in Xinjiang, and although the Tarim basin is thought to contain a substantial portion of China's oil reserves base, several exploration companies have been disappointed in their early findings.

Although there currently is no transfer of state assets to private ownership in Xinjiang, ministerial branches and industries are adopting corporate practices to coincide with market economy policies. Competition, particularly in oil, is encouraged among leading energy companies in Xinjiang.

The recently created China Star Oil Co., a subsidiary of the Ministry of Geology and Mineral Resources, is now engaged in oil and gas exploration activities at Tarim, along with CNPC. Indeed, there are 10 Chinese oil companies now searching for hydrocarbons in Xinjiang, along with a number of foreign firms. A single agency, the Tarim Petroleum Exploration and Development Bureau, a part of CNPC, coordinates the activities of the many companies.

Caveats

While the potential for foreign investment is vast, barriers do exist in the form of insufficient information on industrial enterprises; inadequate infrastructure; an unclear decision-making hierarchy; nonconvertible, nonexistent, or new, untested currencies; and conflicts over resource ownership in scattered autonomous regions.

Other pitfalls in exploiting these resources include inadequate transportation and communications, unstable governmental policies, and political and ethnic conflict-including recent unrest in Tajikistan and civil strife in Afghanistan.

Investors and analysts, therefore, are encouraged to keep informed on economic and political developments in Central Asia, as rapidly changing political, economic, and investment policies can significantly affect the outlook for the region's resource industries.

Acknowledgment

This article was adapted from James P. Dorian's business management report, Oil and Gas in Central Asia and Northwest China, April 2001, CWC Publishing Ltd., London.

The author

James Dorian is an energy and resources economist with the government of Hawaii in Honolulu, where he manages collaborative projects on energy efficiency and renewable energy involving Hawaii and the Chinese and Philippine governments (jdorian@ dbedt.hawaii.gov). Dorian previously was a Research Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu. He has lived and worked in former Soviet Central Asia and has nearly 20 years of experience analyzing the energy markets and economic development strategies of the former Soviet Union, China, and Asia, as well as geopolitical forces affecting the global energy industry. He has published numerous books and articles on oil and gas in the FSU and China, the effects of energy on economic development, and foreign investment risks and opportunities. Dorian earned his doctorate degree in resource economics from the University of Hawaii, where he presently serves as an affiliate graduate faculty member. He has an MS in energy and mineral economics from West Virginia University and a BS in geology from Pennsylvania State University.